In Search of the Garden of the Finzi-Continis, Finding the Courtyard of the Finzi-Magrinis

By

Judith Roumani[i]

On a recent visit to the city of Ferrara, we hoped to retrace the steps of the Finzi-Contini family, famous from the Holocaust-era novel by Giorgio Bassani and its film version. [ii] With one day at our disposal, we decided to start off by attending the guided tour of the Jewish community building. It was on a side street just near the Duomo or cathedral (the ancient ghetto was, as in many places in Europe, located under the eye of the Church). Ferrara in Renaissance times was one of the first cities in Italy to allow Jews to live openly as Jews, under the tolerant dukes of Este. As with the Medici family in Tuscany, the Estes welcomed Jews, and secret Jews, because of their ability to finance the rulers’ vast building ambitions and wars too. We see the results of their ambition today in the magnificent old buildings that characterize the center of Ferrara. Ercole I, the Duke of Este, invited Doña Gracia Nasi to come and reside in Ferrara where, after her many travels through Europe, most recently to Venice, she was able at last to openly practice as a Jew and dedicate herself to saving other conversos from the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions. Ferrara was a center attracting Jewish printers, and the famous Abraham Usque printed there in Hebrew and other languages for about ten years. He produced the famous Ferrara Bible in Spanish or Ladino, of which one edition was dedicated to the Duke of Este and one edition to Doña Gracia.[iii] The city of Ferrara, as well as being beautiful, is also today largely calm and quiet (except on the evenings when drum-playing students invade the Piazza del Duomo): the center is mostly closed off to vehicles and is full of pedestrians and cyclists—not only students but also older, well dressed shoppers and bureaucrats wheel by perched on their bicycles. An almost idyllic scene of cafes surrounding and leisurely conversations being held in the middle of the Piazza del Duomo charms the visitor.

View of Ferrara's main square

Anyone who has seen a few Italian films immediately feels transported into the times of Life is Beautiful or, naturally, Vittorio De Sica’s The Garden of the Finzi-Continis.

And of course those times were far from idyllic. The Jewish community of Ferrara is very small today, about eighty members as opposed to about eight hundred before the Holocaust. Giorgio Bassani’s novel, Il Giardino dei Finzi-Contini, is a sort of memorial to this community, hit hard by the Nazis and afterward subject to emigration and probably assimilation. It is also a memorial to the Ferrara the author knew before the war and during the Fascist period. Bassani himself did not like De Sica’s film version of his novel but probably more people have seen the film than have read the book. The book is said to be a bestseller and has gone into many editions and translations (we discuss here Bassani’s novel rather than De Sica’s film). [iv] Bassani consciously tried to write the novel of Ferrara, and it has been said that the city of Ferrara itself is the main protagonist of all his work. How then could we discover the Ferrara of the Finzi-Continis, in a brief visit to an unknown city, more than half a century after Bassani lived there?

It turned out that we might have some help. Having written ‘the novel of Ferrara’ Bassani has belatedly become ‘the author of Ferrara’. It is ironic that Bassani, the Jew who was excluded from university and the town’s tennis club (this may have pained him the most), allowed to be a teacher only in the private Jewish school, able to publish only under a pseudonym, and eventually arrested in Ferrara for anti-Fascist activities, is now the town’s favorite son. Bassani’s novels were for sale at a book fair in one of the central squares, the Piazza del Municipio, and there was an article that very day interviewing Manlio Cancogni, a fellow writer, who reminisces about him, on the front page of the local newspaper. [v] An exhibit on Bassani, marking ten years since his death, was to open a few days later. [vi] The local tourist board has a recommended Bassani itinerary. [vii] It seems that Ferrara embraces the memory of the Finzi-Continis even though they never existed.

The enormous locked doors of the Jewish community center opened promptly at 12, and we were ushered into the courtyard, where we saw the remains of a sukkah, small compared with those of other synagogues (we had just experienced a noisy, crowded and joyous Simcha Torah in Rome). The building embraced several synagogues, though its external architecture, as is usual in Italy, revealed nothing of its purpose.

Via Mazzini, main street of the ghetto

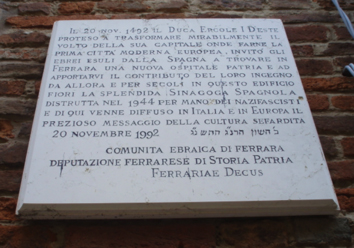

As we mounted a steep flight of stone steps, and noted how they were worn hollow by the footsteps of many generations of Ferrara’s Jews, I had a fleeting vision of Giorgio Bassani and his characters treading those same steps. Only one synagogue, the Scola Tedesca, or Ashkenazi synagogue, is in use today. Its windows had long ago been blocked up on one side, as a synagogue in earlier centuries was not allowed to overlook Christian homes, but it still had plenty of light and is well kept. We did not attend on Shabbat and had no idea of how many worshippers there are on a normal Shabbat. Much of the building is a museum documenting the former grandeur of Jewish Ferrara. One flight higher, the Italian synagogue, heavily damaged by the Nazis, has been partially restored for use as a meeting room. Here the Jews of Ferrara were rounded up before being shipped off to the camp of Fossoli and eventually to the Nazi death camps. Ancient Holy Arks of the Torah stand on one side. Visitors can see the very old Ark that has come from the Sephardic synagogue, or Scola Spagnola, restored in honor of Silvio Magrini. Where is this synagogue, described meticulously in one of the early scenes of Bassani’s Garden? The guide directed us down a narrow side street, where we could see the façade only. The interior has now been converted into modern apartments. There is a moving plaque and commemoration on the outside, but that is all.

Plaque on the building that once housed the Sephardic Synagogue, Scola Spagnola

Door of the building of the Sephardic Synagogue

In Bassani’s novel, Professor Ermanno Finzi-Contini, the head of the Finzi-Contini family, has recently restored this Baroque synagogue. Thus the few families who identify as Sephardic Jews rather than being part of the majority, Italian Jewish community, separated and distinguished themselves by attending this small synagogue and following their own customs. Bassani’s unnamed first person narrator describes in detail how the small Sephardic community of Ferrara held services when he was a child in the restored Sephardic synagogue. The children, partly bored, partly distracted, find a comforting yet constricting refuge under their fathers’ prayer shawls during the blessing of the Cohanim. The tallit, warmly enclosing, like the walled garden surrounding the mansion of the Finzi-Continis, is a symbol of the illusory sense of safety of Ferrara’s Jews before the Holocaust. Another similar symbol is the elaborate family tomb, somewhat like a small, ornate pagan temple, in the Jewish cemetery, in which the Finzi-Contini family had hoped to find its final resting place, and in which only one member of the family was buried.

Who was the real Silvio Magrini and why did he go to the trouble of restoring the Ark of a disused synagogue? For many years Bassani denied that his fictional family was based on any actual people he knew. Then eventually, a few years before his death, he mentioned the Finzi-Magrini family. [viii] They corresponded to his fictional characters in many respects: almost all were deported to the death camps, except one son, Uberto, who had died prematurely of the same disease as the character Alberto in the novel. He is the one who in the novel is laid to rest in the family gravesite. In the corridor of the synagogue building is a plaque in memory of the engineer Uberto Magrini, who died prematurely in 1942. This may have been the last plaque put up after the Fascist devastations on Rosh Hashana of 1941. Another plaque pays tribute to the noble Silvio Magrini, (1881-1944) who was president of the community and was deported in 1944, together with almost two hundred other Jews of Ferrara. The Finzi-Magrini family did constitute a sort of Sephardic and intellectual aristocracy in Ferrara, [ix] and seem to have even possessed a large dog similar to the one Bassani’s heroine, Micol, loved. Their daughter, Giuliana, unlike Micol in the novel, was already married and managed to flee to Switzerland to survive the war, having three children. Her descendents say that her personality was nothing like that of the alluring yet unpredictable Micol. [x] The Finzi-Magrini family did not live on the beautifully proportioned, cobbled Corso Ercole I, with its walled gardens, but on a parallel street close by, in a more run-on-of-the-mill, old yet elegant apartment building.

Corso Ercole

Great wooden doors greeted us, we half-expected another plaque though there was of course none, but a kind resident did allow us to enter. The courtyard was small and prosaic, at least for Ferrara.

Courtyard of the Finzi-Magrinis

Courtyard of the Finzi-Magrinis

A nearby courtyard on the same street

They lived not on the edge of town but in central Ferrara, removed from the ghetto but not far away. Giorgio Bassani is said to have found his inspiration for the novel in a garden, or rather private park, that he visited later in Rome. In fact, I did visit the garden of Mussolini’s villa, in the older suburbs of Rome, an area of ivy-covered villas and embassies, near the Via Nomentana. The park (now a public park containing an art museum) has winding gravelly paths, overgrown thickets, trees of many species, and even an alpine chalet-style folly. Young bridal couples were posing against dark foliage and as twilight fell it seemed that it clearly could have served Bassani or a filmmaker like De Sica on location, as a model. [xi]

After the war, Bassani wished to respect the memory and protect the privacy of individuals he had known, in the provincial atmosphere and relatively close-knit Jewish community of Ferrara. [xii] The human weaknesses he describes in his nineteen-forties Ferrara if anything endear his Jewish characters to us and underline the utter injustice of the cataclysm that hit them totally unaware. From our post-Holocaust perspective, we can see the writing on the wall in every incident, but Jews of longstanding loyalty to Ferrara and Italy, secure in their places in life and in the city, felt that taking steps like building their own tennis court, or founding their own school when Jewish teachers and schoolchildren were excluded from public schools by the Fascists, were aappropriate and adequate responses to the Fascist/Nazi threat. Bassani himself became a teacher in this school. After publishing under a pseudonym, being imprisoned for his anti-Fascism, then released, Bassani moved first to Florence, later to Rome, always continuing his anti-Fascist activities. His novel embodies the regret and bitterness that we find in almost every survivor’s story, and is an elegy to the once flourishing Jewish community of Ferrara, now a shadow of its former self.

Ferrara at dusk

Notes

[i] Judith Roumani is the editor of Sephardic Horizons, a member of the planning committee of the Vijitas de Alhad, and president of the Jewish Institute of Pitigliano. Her field of research and her publications are in modern Sephardic literature. The photographs are by Jacques Roumani.

[ii] Giorgio Bassani’s novel was first published in 1962 (Turin, Einaudi, 1962) and has seen many editions. There are at least two English translations, of which William Weaver’s, with a literary introduction by Tim Parks, is the most recently published (New York: Knopf, 2005).

[iii] See Annamarcella Tedeschi Falco, Ferrara: Guide to the Synagogues and Museum (Venice: Marsilio, 2000) for much detailed information on the synagogues of Ferrara. For more information on the Ferrara Bible, and for excerpts, see Moshe Lazar, ed., Sefarad in my Heart: A Ladino Reader(Lancaster, CA: Labyrinthos, 1999). For Doña Gracia, see Andrée Aelion Brooks, The Woman who Defied Kings: The Life and Times of Doña Gracia Nasi (St. Paul: Paragon House, 2002).

[iv] An interesting development is the turning of his novel into an opera, commissioned by the Minnesota Opera, and to be performed in 2012.

[v] Rita Castaldi and Antonietta Molinari, “Il Ricordo di Bassani,” La Nuova Ferrara Oct 7, 2010, p. 1.

[vi] “Giorgio Bassani: Il giardino dei libri” Announced in http://www.estense.com/mostra-e-letture-per-il-decennale-di-bassani

[vii] For tourists wishing to make a tour of “I luoghi di Giorgio Bassani” the tourist board recommends the house where he was born, the school where he taught, the library where he studied, the family grave, etc. See http://www.ferraraterraeacqua.it

[viii] The Nazi archives of Bad Arolsen reveal the fate of Silvio Finzi-Magrini and his family. See Marco Ansaldo, “La vera storia dei Finzi-Contini,” in the Italian newspaper La Repubblica, http://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/2008/06/13r2

[ix] Silvio Magrini was also a scholar and professor at the University of Bologna. His publications cover the fields of physics (magnetism), history of science, the history of Ferrara, and Zionism, his works appearing in the first three decades of the century. There is even a bibliographical reference to his work in the Encyclopedia Judaica. He was probably one of those Italian Jewish academics who were dismissed from the universities in 1938 when the Fascist Racial Laws were decreed.

[x] See the article by Marco Ansaldo, cited above.

[xi] Afterwards I learned from Guido Fink’s article (cited below) that Bassani was indeed inspired by the gardens of this villa, the Villa Torlonia, that Mussolini had occupied for about twenty years, and that after the war was left in a state of neglect for several decades. Its website tells us that in the 1920s Jewish catacombs had been discovered in its grounds, and Mussolini had turned them into an air raid shelter.

[xii] Even the name of the city in his earlier stories was simply ‘F.’ until they were published together in 1956 as Cinque storie ferraresi. See Guido Fink, “Growing up Jewish in Ferrara: The Fiction of Giorgio Bassani, a Personal Recollection” Judaism (Summer-Fall, 2004), accessed on BNET,http://findarticles.com. Fink however tells us that Il Giardino caused scandals anyway—from those who felt they were represented in the novel, those who felt they had been left out, and those who felt they were underrepresented—“some people did recognize themselves in the characters of the book, or did not and were disappointed, or did recognize themselves but not enough.”