Doer and Dreamer: An Interview with Raffaello Fellah

(Tripoli 1935 – Rome 2008)

By Harvey E. Goldberg*

Libyan Jewish Basketball Team with Raffaello Fellah in the front row on the

left.

As an anthropologist and field researcher, I find it apposite, in an anniversary volume of Sephardic Horizons, to share with readers my experiences with a person who has expanded my horizons. I first met Raffaello Fellah in the late 1970s on a trip of his to Israel. He had heard of my work concerning Jewish life in Libya, and invited me to visit him in Rome the next time I was abroad. About half a year later, after a conference in the US, I planned a stop in Rome for 2-3 days. Arriving at his office near Viale Libia, I accompanied Raffaello during his scheduled activities and we chatted about mutual interests at every possible break. Either that very evening or the next, he told me that he had arranged an event in which Albert Memmi and his wife flew into Rome, and Memmi would give a talk in a bookstore. After that we, and some other associates, would dine together.

I think the occasion was when an Italian translation of one of Memmi’s books appeared. This obviously excited me. Memmi’s Pillar of Salt was one of the first books I read when my interest in North African Jewry began to develop as an undergraduate. I thus was quite surprised when, on the way to picking up Memmi to bring him to the bookstore, Raffaello asked me to explain why Memmi was well known. I don’t remember my brief answer, but I think it impressed Raffaello because one of the points I mentioned in fact came up during the talk. That was the beginning of an active relationship between us, that continued until the mid-nineties, in which I was a kind of cultural consultant and assistant to Raffaello in his initiatives to place Libyan Jewry “on the map” in the framework of his own imaginaire that also encompassed Sephardi Jewry, Israel, and the Arab World.

Our backgrounds were quite different. Born in 1935, Raffaello grew up speaking the Jewish dialect of the local Arabic and his basic education was in Italian. In high school he learned French, but left school before graduating for that was precisely the time of Israeli independence and the possibility of large scale Jewish emigration (that began in April 1949). Raffaello did not have the patience to sit in school in the midst of current events that also led to Libyan independence at the end of 1951. The different trajectories of our respective educations notwithstanding, we shared many perceptions of society and political developments. While never having heard of Pierre Bourdieu, Raffaello’s vocabulary included ‘cultural capital’ when he spoke of the potential contributions of different ethnic groups to Israeli society. I once asked him how he learned English. Waving his grasped hands in front of him he replied: “I grabbed it out of the air.”

While we found much in common in our discussions, there was a big difference between us that probably also became a basis of our friendship. I had chosen a path of seeking to understand social forms and cultural expression, while Raffaello was intent on changing things. In the following paragraphs of this introduction, I briefly will sketch some of his activities and their outcomes while he still was in Libya, after arrival in Rome, and with reference to Israeli society. The main part of the paper, following that, is a transcript taken from a series of interviews carried out in August 1989 in which Raffaello explains and reflects upon some of his accomplishments—and also his disappointments—over the previous 20 years. For me they constitute a conversation that deserves to be continued.

Raffaello Fellah: Background and Activities

A Tripoli-born businessman who moved to Rome, Raffaello provides an example of the discovery of history among the Jews of Libya. He was born in 1935 and died in 2008. One of his early memories was that of a military parade in his native town, which impressed upon him the might of German armor and discipline. Only later did he learn that this political and military power had been turned brutally against his own people. At the beginning of 1943, Axis forces were driven from Tripolitania by Britain’s Eighth Army. In November 1945, a riot broke out among the Arabs of Tripoli and of the neighboring villages, as a result of which over 130 Jews were killed. Raffaello's father was murdered during this pogrom.1 He has stated that the memory of his father, and his mother's loyalty to that memory, were among the main motivating factors shaping his economic, political, and cultural activities.

The majority of Jews in Libya (more than 30,000) emigrated to Israel during the years 1949-1951. Raffaello was among the approximately 4,000 Jews who remained in independent Libya in 1952.2 Utilizing his inheritance, he became an active businessman working along with Arab partners as required by Libyan law.3 In 1967, during the Six-Day War between Israel and her Arab neighbors, the Jews in Tripoli felt themselves in mortal danger and a number were attacked and murdered. Their situation became untenable, and most left for Italy as soon as the government agreed and made it possible for them to do so. Two and half years later, Mu`ammar Qadhafi came to power, and the following year his government confiscated all the property of Italians and of Libyan Jews.

Upon settling in Rome, Raffaello immediately became active with others in organizing a refugee group to lay the groundwork for claims against the Libyan government. While always a ‘man of action’, he also had been keen to press the cultural side of his economic plans and political convictions. When it was learned that the Libyan government planned to build a road across the ancient Jewish cemetery in Tripoli, Raffaello mobilized all the connections he could muster seeking to prevent this step.4 He met with the Libyan Foreign Minister when the latter came to Rome. Another tack was to attempt to influence the contractor working on the road, a Muslim from Crete. When these efforts came to naught he began to think in a new direction.

Raffaello initiated the construction of a monument, in the cemetery of Rome, dedicated to all the Jews buried in Libya. The memory of his father was a motivating force, but he also sensed the importance of the cemetery to all the Jews. He commissioned a young friend from Tripoli to design it, along with an Italian architect, both working under the supervision of the noted architect, Bruno Zevi. In Raffaello's own words: "I tried to develop an idea of great significance, and had sand brought from the Libyan shore, with the help of my [former] partner. The steel represents the bulldozer, the violence which brought the cemetery to its end. I was pleased with the work."5

When it was ready, we organized a ceremony with the Union of Italian Jewish Communities. I gave Abe Karlikow, from the American Jewish Committee,6 the honor of unveiling the monument, and Professor Zevi gave an address on the design. I spoke about the communal and political implications of the initiative.

Given the pressures of daily life, it is easy to forget that you belong to a people, including my own Libyan community. But I said to myself that I cannot abandon the memory of centuries of people who had died there, including my father. Something had to be done to memorialize the community and to remind people of their past in Libya. I received many positive reactions and messages of approval. Till today, close to Rosh Hashanah, many Libyan Jews visit the monument and recite Kaddish there along with a memorial prayer.

This was only the beginning of Raffaello's efforts to establish a past and historical continuity for the Jews of Libya. About the same time, he ran across a book on the history of the Jews of Italy, and asked himself why is there no parallel book on his own community. He turned to leaders of the organized Jewish community in Italy, and they provided him with the names of historians capable of doing work on the subject. Raffaello turned to Renzo De Felice, and commissioned him to write such a book. De Felice’s work on the Fascist period demonstrated his extensive familiarity with Italian government archives.7 Parallel to that, Raffaello’s acquaintances in Italy, England, and Israel placed additional documentary material at the historian's disposal. The result was a major publication, in Italian, that appeared in 1978 with financial assistance by Raffaello.8

Rome became Raffaello's main home but, as the memorial and his linking up with De Felice indicate, this did not imply an erasure of his Libyan past.9 In Italy he worked with people familiar with local industry and became a middle man for exporting goods to Arab countries including Libya. It was in Raffaello’s office that I first had the opportunity to directly witness interaction between Libyan Muslims and Jews. During my first time there, several visitors came from Libya. One was an older man and a long-time friend; Raffaello immediately introduced me, saying I was from Israel. For Muslim travelers, it was then not easy to obtain ḥalal meat in Rome: the kosher food in Raffaello's office was one way of observing Islamic rules. The following day, two younger Libyans whom Raffaello never had met before came on a business visit. This time, he asked me to sit in a separate room when they first arrived. After half an hour he introduced me, again mentioning my Israeli provenance.

A natural continuation of Rafaello’s Libya-oriented activities in Rome was extending them to Israel. Most Jews who remained in Libya through 1967 had relatives, and certainly friends, there. Raffaello’s eldest sister had moved there with the initial large immigration, but his vision was broader than family matters. He sought to mobilize Jews from Libya in Israel to work together with him on ambitious projects. He organized “Libyan Jewry Week” in 1980. This entailed a photo exhibit at Tel Aviv’s Museum of the Diaspora including an appearance by President Yitzhak Navon, an academic symposium linked to the launching of a Hebrew translation of De Felice’s book,10 and a documentary film on Jews in Libya (my wife Judy and I had introduced him to an Israeli producer to help realize this project). The week also included entertainment in which traditional dress and food were featured, and these were highlighted in a visit to moshav Dalton in the north that had been settled by people from a small community in the mountains south of Tripoli.

Raffaello was not the first to seek to preserve and promote Jewish heritage from Libya. The most prominent effort earlier was taken by Rabbi Frija Zuaretz (1907-1993), who was born in Tripoli, served as rabbi in the coastal town of Khoms, was active in the Zionist cultural awakening in Libya, and became a leading figure in the processes of immigration adjustment to Israel. He first was linked to the religious Po’el Mizrahi party, that later became part of the National Religious Party under which the Committee of Libyan Communities in Israel (Va’ad Qehillot Luv Be-Yisrael) was formed.11 Functioning as a landsmanshaft, the committee also undertook projects to perpetuate Libyan heritage, in particular a “memorial book,” Sefer Yahadut Luv in 1960.12 Another immigrant association existed associated with the Mapai (later Labor) party and led by Avigdor Roqah, but had less of an emphasis on cultural continuity in its projects of immigrant integration. Raffaello established contact with both these leaders.

According to Raffaello these leaders were hesitant about the sudden appearance of a newcomer, but eventually ended up cooperating to some extent. After the splash of Libyan Jewry week, he looked toward long-term collaboration. He argued that by this time (the 1980s) Libyan Israelis should leave political attachments aside when focusing on their common past. After many years a new volunteer body—The World Organization of Libyan Jews—was formed and the older associations became defunct. Along with this process was the idea of establishing a heritage center, and discussions were carried out in some cities with large populations of Libyan immigrants. After several attempts such a center emerged in Or Yehuda and was formally founded in 2001.13 The model for all such enterprises is the Babylonian Jewish Heritage Center, founded in 1973, that also is located in Or Yehuda.14 In 2007, a law passed in the Knesset provided the Libyan center with a firm official footing, and is the basis of some annual support from the Ministry of Culture and Sport.

Raffaello differed from these leaders at another level as well. The ties he felt to Libya were also relevant for the present and for him it was natural that this sentiment coexisted with an attachment and commitment to Israel. What some saw as a "paradox" was for him a source of empowerment, making him and other Jews from Arab countries potential mediators between Israel and the Arab world. This basic assumption motivated all of his public activities even when it was not declared explicitly. The concluding segment of this introduction sketches a grandiose and still puzzling project in which Raffaello was a major player several years after our interview.

The larger political scene was shifting considerably during this period. The bombing of a Pan Am plane over Lockerbie in December 1988 gradually led to accusations of two Libyans, and of Libya herself, as responsible. In March 1992 the UN imposed sanctions that isolated the country at many levels. The same period saw Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait that an American-led coalition, including forces from Arab countries, pushed back beginning January 1991. Two Arab countries that were not part of the coalition were Iraq and Libya, although there were some reports that Libya considered joining as Mu’ammar Qadhafi also sought to extricate himself from his rogue status. Raffaello, at some point during these years had visited Libya and made contact with Qadhafi. Along with a small network of contacts a plan was launched that would place Libya in a central place regarding relations with Israel.

When Qadhafi’s revolutionary government had confiscated the property of Jews in 1970 the law stated that in the future compensation would be made in the form of government bonds. This never took place, but continued to exist as a point of contention and, at times, negotiation. A move of reconciliation with Jews from Libya would signal a new relationship with Israel on the part of an Arab state as well. The way this step was taken was both dramatic and roundabout, one might even say bizarre,15 entailing pilgrims from Libya who ostensibly had begun a journey as Muslims fulfilling the obligation to visit Medina and Mecca, but ended up reaching Jerusalem.

As presented by Maurice Roumani (pp. 217-20), the plan behind this brief incident, that made headlines for a few days bridging May and June in 1993, probably was brewing for 2 years. One narrative appearing in the media claimed that a group of about 200 Libyans who had embarked on the Haj became stranded in Egypt because Saudi Arabia refused them entrance in compliance with UN sanctions. In this version, the group took a decision to cross the Sinai peninsula and visit the holy places in Jerusalem instead. By all indications in the Israeli media, the government was taken by surprise,16 and debated how to react to the news. It was decided that the Minister of Tourism (Uzi Bar’am) would head to the border crossing at Rafah and greet the pilgrims, joining Raffaello and others who had worked with him including Libyan Israelis.17 The reception between the Muslim pilgrims and Libyan Jews was warm and moving, lasting more than an hour, after which the pilgrims were transported to the Hyatt Hotel in Jerusalem. During some free hours in the hotel lobby the relaxed cordiality of that initial meeting repeated itself, but the more formal and public aspects of encountering Israel society soured. On Israeli TV some well-known media figures aggressively challenged the spokesman of the group (who was a hand-picked Libyan official), and on another program the Deputy Foreign Minister referred to Libya as a “leper state.”18 After a visit to the Haram ash-Sharif the following day, the spokesman told the press that Jerusalem should be liberated from Israeli control.

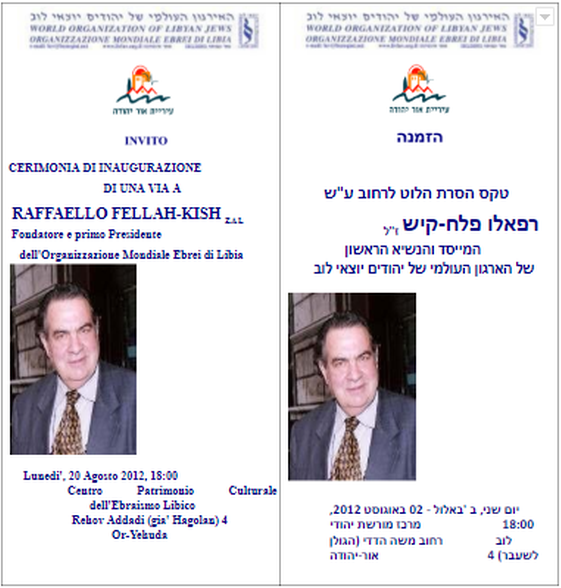

Raffaello Fellah Street naming invitation.

This incident too, which rapidly receded from memory after grabbing international headlines for a few days, took place after my interview with Raffaello. But it resonates with my final question to him in which I mention visits by Moroccan Israelis to the country of their birth, who meet Moroccan Muslims who still have positive memories—and at times current information—about former neighbors now living in Israel. In retrospect, it seems clear that Raffaello’s “holistic” approach, in which high-level politics and intimate relations were interwoven, was one factor attracting my personal and anthropological fascination.

The transcript that follows is from one of a series of interview sessions that took place in Rome in August 1989. The topics ranged from details of Raffaellos’s life in Libya through his most recent activities relating to the Jews in Libya. The theme of this session was an elaboration of Raffaello’s cultural entrepreneurship, beginning with his search for someone to write on the history of his community. The interviews were recorded, and were transcribed by Judith Goldberg in the fall of that year. There are occasional short gaps where words or parts of a sentence were not audible.

My active relationship with Raffaello tapered off in the mid –nineties, but his activities relating to the Jews of Libya continued throughout his life. At a memorial service in at the Heritage Center in Or Yehuda, about a year after he died, Ben-Zion Rubin called him “the Herzl of Libyan Jewry.” It is reported that he died as he lived, passing away in the midst of his efforts, soon after giving one speech on behalf of Libyan Jewry, and while preparing for another one. In 2012, a small street near the Heritage House was named after him.

Interview: Presenting the Past with an Eye on the Future

H: Tell me about your efforts to have Libyan Jews be more aware of their history.

R: At the time when some of the Libyan Jews were taking an interest in the issue of our claims on Libya, I came across the book by Renzo De Felice on the history of Italian Jewry during the Fascist period. I said to myself that in order to keep interest in the Libyan question from waning, I should make sure that someone writes a book on the history of the Jews of Libya.19

H: When was this?

R: The end of 1971 or the beginning of 1972….I approached the President of the Union of Italian Jewish Communities, to get his advice on the right historian to undertake this task. And he recommended two names, one was De Felice. . . . His first recommendation was De Felice because he had dealt with the topic of Italian Jews under Fascist rule. In that context, he already was acquainted with certain aspects of the history of the Jews of Libya. He was very familiar with the papers of the Italian Administration.

H: He must have also worked with the Union to write that book, and knew their archives.

R: He was very acquainted with their archives and the archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Libyan Jewry was under the jurisdiction of that office.

H: What happened when you broached the idea to De Felice? Was he interested in the project?

R: He said that he was, and that the President of the Union had already spoken to him . . . We began to discuss it . . . . I agreed that a premium would be paid for the work, and the expenses of his research. I told him I would cover the cost of an assistant to work in the archives, make photocopies, and things like that.

H: Was there any other help that you provided?

R: He asked me to secure the cooperation of the Jewish community. There were many events that could not be understood without the explanations of people who lived through them. I was pleased about that.

H: So the book is not based solely on archival research?

R: It mostly is based on documents, but not entirely.

H: Were you able to provide him with a lot of additional information?

R: I brought him documents, other material, and people to be interviewed. Those included both Jews and Arabs. He also recognized that the book could not be based only on documents found in Italy. I arranged for research in the Zionist archives by Simonetta and in the Public Record Office in London by Dino and Janet Naim, based on De Felice's request for documents.

H: I had always wondered how in a short time he got to so many different sources.

R: You could say that formally he was commissioned to write the book, but he immediately became very personally involved and worked very hard to find all sorts of material.

H: What was your relationship when it came to the stage of writing book?

R: Whenever he finished a chapter he gave it to me. He asked me to try to find documents to strengthen certain points, or to find people who could enrich a topic with their oral testimony.

H: Was his picture of the history of the Jews of Libya the same as you had understood?

R: There were some points that didn't satisfy me, but most were not major. On one historical issue there was significant disagreement, and we also clashed on one technical matter. Both involved politics.

H: What was the historical question?

R: I disputed the way he dealt with the 1945 pogrom.20 His mention of British involvement was not convincing. In order to arrive at the true version of the events, I said, you have to look at other sources, the testimony of people who were there. He replied that I must base my claim on documentation. My answer is that there can never be written documentation which will show British responsibility as clearly as oral reports. He said that he could take my point of view into consideration, but could not make a serious historical claim on oral testimony alone.

H: Whose opinion prevailed?

R: Let's say there was some kind of compromise. De Felice's book does show that the British failed to take necessary precautions when the first warnings of rioting were sounded and that they were very slow to intervene. He thus was able to point to doubts about the British role in the events, and indicate that they bore partial responsibility.

H: Did you bring him any people to talk about the riots.

R: I brought him [Giacomo] Marchino, [Roberto] Nunes-Vais,21 and Vittorio Naim, very serious people. He also spoke to Arabs that admitted that the British were responsible for what happened. I understand the position of the historian who does not wish to publish conclusions that are not based on written documentation, but the people who saw and lived those events will be the real judge.

H: As you go back in time, it becomes more difficult, and then impossible to find eye-witnesses to historical events.

R: The tension was inevitable. He was a historian who wanted papers and documents, and not the testimony of people. In my opinion, however, certain chapters were still weak in certain aspects. I knew this from what I had heard, and I tried to find people who could give reliable reports on the events of those periods.

H: Did the idea ever occur to you of being a kind of co‑author, or a secondary author with De Felice?

R: No, I could never have pretended that even in my [dreams?]. I just say, I have to introduce the book with the reason [for the] book. Milena [Pavan] worked very hard on this project as well.

H: You said there was also a technical disagreement between you and De Felice.

R: That had to do with the timing of publication. It was about then that Qadhafi began to engage in terrorist activity abroad. I received some warnings, let's say from the secret service. I was told to be careful of my life.

H: De Felice must have worked on the book for over five years. Was he included in this warning?

R: It was mostly for me. It did not relate only to the book, but to my activism on behalf of the Jewish community. I was worried and wanted to postpone the publication of the book. De Felice had his contract with the press, Il Mulino, and wanted the book out. He therefore was angry. Eventually, the book came out more or less as scheduled.

H: Did you have any idea of restricting the circulation of the book?

R: On the contrary. When it was published I sent a copy of the book to the Libyan Ambassador in Rome. My hesitation was mostly a matter of timing.

H: When De Felice wrote his book on the Jews in Fascist Italy, had that been at his own initiative, or was that also in cooperation with the Italian Jewish community.

R: With the Jewish community, and when I compare myself with them it makes me proud of my effort. It took the Jewish community of Rome and the Union of the Italian Jewry two or three years to succeed in financing the research. I was able to do it myself in a shorter period of time.

H: You didn't turn to anyone else to help you?

R: I did. I accepted a $1,000 contribution from the American Jewish Committee; I got this with the aid of Abe Karlikow.22 He was the only one who concretely supported the project at that time. No one else gave a penny.

H: With regard to the first book, did the Italian community raise money from private sources or was there some sort of general campaign?

…

H: Don't you think it would have been better to try to involve many different Libyan Jews in this project?

R: I had hoped that involvement would be widespread. However, when I brought up the idea of a history of the Jews of Libya, most were uninterested. The President of the community asked: "What kind of history do we have?" The most people like Nunes-Vais, Hayyim, and others . . . were willing to do was to be interviewed. They went to De Felice to be interviewed only as a personal favor to me. I found a lot of resistance. People were not prepared to make any other effort, to look for papers, letters, or other documents to give him. I was concerned that he would finish the book without having adequately covered the topic of the life of the Jews of Libya. I had expected much more cooperation from my people, but received just passive cooperation.

H: How do you explain that?

R: Some people were not eager to cooperate with De Felice because they wanted to keep material they had for themselves. An example is Lillo Arbib who is very acquainted with different periods and various episodes of the history.

H: He most likely had the idea of writing a book himself.

R: In fact, I recently helped him get a small book published.23

H: Basically people seem indifferent to history.

R: When I began working with De Felice, I sent a circular letter to 100 persons, to various leaders, explaining that I wanted to produce a book on the history of the Jews of Libya. I asked them to cooperate, to collect their memories on some historical matters. The reaction was always cold. They have no appreciation of the meaning of 2,000 years of existence.

H: Did you seek the cooperation of Libyan Jews living in Israel?

R: When I was working on the book, I sent another circular letter to the Libyan synagogues in Israel. I also wrote to [Rabbi] Frija Zuaretz, who was the first leader of Libyan Jews to make an effort to document our history.

H: I think he worked on that at the same time that he was elected to the Knesset.24

R: I arranged for Zuaretz to be received by the Libyan community at that time, Lillo Arbib …and the Italian Cultural Center.

After that I organized a conference in the Ramat Gan synagogue, to present the project with De Felice. Rabbi Frija and Benzy25 were there, and so was Arkin, from the Jewish brigade that had been in Tripoli.

H: You mean the person who had been appointed as mayor of Tripoli under the British Military Administration?

R: Yes. He came with his uniform…because he was a general in the reserves.26 That was the first time I met him.

H: How did people at the conference react to the idea of the book.

R: Without much enthusiasm. Zuaretz was willing to get up and speak, but I noticed that he was very reserved. He was not prepared to fully endorse the effort. He asked: how can an Italian, who is not Jewish, write the history of the Jews of Libya? He has never had experience with the community and has never even been to Libya. On the other hand he wished him success with the work.

H: How did you present the matter?

R: I stressed how important it was that a well-known historian from Italy have the cooperation of the community. He especially needed their help to deal with the topic of the Libyan Jews in Israel.

H: People in Israel and in Italy reacted pretty much in the same way.

R: That was the reaction that had to be overcome. The aliya of 1950 brought about a divorce between the two parts of the community. Those immigrating to Israel were involved in a new problematic dictated by the Israeli reality. They faced hard work in order to become established in the new society, and suffered from the shock of meeting a very different religious situation from that which they had known in Libya. They were also focused on the future attracted by the idea of the new medina (state), while the Jews who remained in Libya sought to downplay reminders of their distinctive history. For these various reasons, Libyan Jewish history was eclipsed. Except for Frija Zuaretz and the few people around him, little attention was given to the importance of the past.

When De Felice was close to finishing his work, but before publication, I organized a ceremony presenting the research, the conclusion of the work. This took place in the Jewish club in Rome. The President of the Union was there, the Cultural Attaché of the Israeli Embassy, and some major personalities of our own community. The presentation gave a negative impression to some people.

H: I remember that when the Hebrew translation of the book was discussed in Beth Hatefutsoth [ Museum of the Diaspora] in Tel Aviv, there was also some controversy.

R: From a certain point of view our community is too proud. At the Tel Aviv meeting someone protested when it was mentioned that people suffered from trachoma, or mention of the poor made some of the participants angry. All that is objective fact. There are documents relating to the problems of health and the social conditions of the community. De Felice discusses these in the book but our people don't like to hear it.

H: Were there any objections that were politically motivated?

R: That too. The book cites a story in which one Jew was believed to have cooperated with the Italian occupation force in 1911. He acted as a spy, giving information on where to bomb Tripoli. Some objected to this being included, so as not to give the impression to Libyans that the Jews collaborated in the occupation of Libya. People want to mold history the way they like it. They want to hear what pleases them, not the facts. You follow me, Harvey?

Inauguration of Memorial in Rome to Honor the Deceased Buried in Libya, courtesy of the late Raffaello Fellah.

H: You can never write a book that pleases everyone. As I stated, there were some people who were unhappy when Mordekhai Hacohen wrote his book.27

R: I think this reflects that fact that our people have reached only a certain level of culture. I can give you another example from some of the reactions I got when I organized a memorial monument in the Rome cemetery.

H: You mean the memorial sculpture commemorating the Jewish cemetery in Tripoli that was destroyed under Qadhafi?

R: That's right. Some people complained: "Why did you include an inscription in Arabic? What is the purpose? An inscription in Italian and Hebrew is enough."

H. Why did you include Arabic?

R: There is an important message. I wanted the monument to be an act of accusation to the Arab people of Libya, even though not many of them were likely to see it.

H: Did anybody feel that there should not be Arabic script in a Jewish cemetery?

R: No, there were no religious objections, but people did not like my concept.

H: Even with regard to the memorial there was no communal unanimity?

R: Not only did some people complain about the inscription in Arabic, but I heard somebody asking how much money I made by putting up the monument. It cost me about one million and a half [Italian] lire which I was very happy to cover. It was a project that was carried out the right way.

H: Tell me about the publication of the Hebrew translation of De Felice’s book?

R: The book would never have been published if I had not gone to Aryeh Dulzin, who was then head of the Jewish agency. I was introduced by Mordecai Mevorakh, he was the head of the Sephardi department at the time. He suggested to me to meet him. The first time [we met he said] here “is one of the meshugaim (people crazy over an idea).” I told him, Mr. Dulzin, I arranged for publication of that Italian book, and I intend it to be published in Hebrew. Let's have a 50‑50 deal. I will cover the expense of the translator, and [want to] to have certain number of books. The Jewish Agency will have to pay the publisher half of certain [publication costs]. It took four to six months and it was done. If I had asked him: let's please give… from the WOJAC (World Organization of Jews from Arab Countries)… to be published…another three years might have passed. He said, okay. We'll submit it to the committee and so on, and that's how it came out.

H: The translation was published in time to coincide with the opening of the photographic exhibit on Libyan Jewry at Beth Hatefutsoth?

R: Yes. I handled the Bet Hatefusoth matter in the same way. They said that they did not have budget, but were interested if I were ready to cover the expenses. I agreed. It was crucial to have a Bet Hatefusoth exhibition on Libyan Jewry. It cost 5,000 dollars, which was not cheap. But I achieved what otherwise would not be achieved. For example, we brought President Navon to the exhibit opening.

H: Let me give you my overall reaction to your depiction of communal inactivity on the part of the Libyan Jews.

R: Please, go ahead.

H: Maybe what you said about the Libyan Arabs in relation to their nationalism is true of Libyan Jews also. Perhaps, in the Libyan reality, it was too easy for the Jews to make money and develop their own personal fortunes. They lived in a country where the level of education was very low. The Jews could read and write, they knew Italian, so they easily monopolized business. There was little need for them to struggle, to organize, or to adopt a long range view of things. When they arrived in Rome, therefore, they were not prepared to form a strategy at the communal level.

R: That is true up to a point. They knew how to overcome their personal difficulties, but did not know how to work on social or communal problems. Nevertheless, there were leaders who immediately succeeded in establishing two synagogues and in opening a kosher butcher shop.

H: Your style of activism is quite different from that of the other leaders of the community who have made efforts to preserve the group's heritage.

R: Among the older generation, my activism was not always well-received. In certain ways they viewed it as harming them; that I was supplanting their accomplishments. There may have been a bit of jealousy, because they believed that they had done as much as was possible to represent Libyan Jewry. I see things differently. I claim that without the contributions of people like Rabbi Frija Zuaretz or Frija Tayyar,28 we could not reach what we have reached today. They have the merit, the zkhut, of being the people who started the work.

H: Do you state this publically?

R: I always am careful to honor those people in the events I organize, to give them kavod (honor) for what they have done. During the first week of Libyan Jewry, I felt that many of them were upset. "Who is this man from abroad who wants to give us lessons? He wants to show us that what we have done here in Israel is nothing compared to what he has done!"-- that appeared to be their attitude.

H: How did you handle the situation?

R: As I stated, President Navon was the guest of honor at that reception. I told him that this was not my event, but was prepared with the cooperation of all the leaders of Jews of Libya, Lillo Arbib, Rabbi Zuaretz, and so forth. I emphasized that it was not my purpose to take anything away from them. I had no interest in excluding other people from center stage. I was prepared to say that even about people who never did anything important. I wanted to demonstrate that I had not come to take, but to give. Everyone would receive the kavod to which he was entitled.

H: Did they appreciate this gesture?

R: At first it was difficult for them to acquiesce to my role, to pass the banner of representing Libyan Jewry to younger people. They did not act as a grandfather whose work was for the sake of his children. In recent years, however, Rabbi Zuaretz has been more accepting of me.

H: To whom else did you give recognition.

R: At the ceremonies I called attention to the contributions of many different individuals to the life of our people. On Libyan Jewry week I brought Emma Polacco from Rome to Israel, along with other people. She was one of the most important teachers of the last generation in Libya. Danny Lotan . . . gave her recognition. I'm sure you remember Regina Mimoun too, who represented the volunteer work of women.

H: If you think about it, the list must be endless.

R: Undoubtedly. I am sure that I forgot some other people who are very important, but symbolically I want to recognize everybody. There is one category of people who I believe have carried the torch of our traditon, the gabbaim of the Libyan synagogues.

H: The laymen who do the necessary work to keep a synagogue going.

R: They, more than anyone else, are entitled to kavod. They began with small things, organizing prayer in a hut in the ma`abarot, the immigrant transit camps. Today, there are probably about 100 Libyan synagogues throughout Israel. The preservation of the Libyan minhag (local prayer liturgy) is the glue that keeps everything else together. It is the stuff upon which the other projects, the events, the books, are built.

H: How do you recognize their contribution?

R: I do my best. When Haim Khalfon published his book on the life and customs of Libyan Jews, I sent 100 copies to gabbaim around the country.29

H: I see you have tried many different avenues of activating the involvement of Libyan Jews. How do you see your efforts today, in retrospect?

R: If I had realized at the outset the amount of time and money I would be spending, I undoubtedly would have done things differently. I did things day by day, however, without an overall final plan. My direction was determined by quality of cooperation that I got. At first, the Nahum brothers, the lawyers in Tel Aviv, were very active. I was much more involved with Libyan Jews in Israel on an ongoing basis, even from Rome, because they reacted to my initiatives. When people became indifferent, the work became much more difficult. I couldn't deal with the everyday problems in Israel but wanted to be involved only at the key decision points. Now I know that I have made mistakes, and could have spent my money and efforts better.

H: How much money have you put into the subject of Libyan Jewry?

R: You can call it, if you wish, the Libyan Jewry disease. I never guessed it would affect me so heavily. It cost me, over the course of 20 years, at least 2 million dollars in cash. During that period, as you yourself can see, at least fifty percent of my working time is devoted to that subject. I am working 12‑14 hours a day, including weekends.

H: You mean that it cost you even more if you were to figure devoting all that time to business.

R: Not only that; it harmed my business. There were many potential clients in the Arab world, particularly in Libya, who said they would like to do business with me, but were hesitant to do so because of my visibility in the cause of Libyan Jews.

H: Those activities attracted attention here?

R: When I say Libyan Jewish activities, I mean the general Jewish cause as well. I focus on the topic of Libya because it is my duty and my natural entitlement. But it is linked to all my other Jewish concerns: WOJAC, the Sephardic Federation, and the World Zionist Organization. When I sit in my office and do business, these issues are constantly part of my program, and people are aware of that.

H: You organized all these events independently, even when it was in the name of the Association or some other body. You even mentioned putting together events that were more dazzling than those of other Jewish groups. There may be a flaw in such an approach. While the immediate impact of these high quality accomplishments is impressive, the fact that other people weren't cooperating means that no group is being built in the process. There is no basis for further mutual involvement.

R: I'm glad you're being frank.

H: Perhaps, in terms of the long-range goals, it is better to leave less of an impression, make mistakes, and even have disagreements. People build up ties with one another by working through their differences. Arguments sometimes show that people share the same ideas about what is important. When you build a tradition of working together, it may be possible to go further in the long run.

R: I agree with your logic, but, believe me, I tried the step-by-step approach and it has not succeeded. Maybe that is because of my limited capacity. That was the concept behind the . . .[effort] in Israel. I tried to create a group of scientists . . . . you remember you [yourself] were appointed . . . . I have to admit that it failed because of the lack of cooperation.

H: How do you interpret the lack of cooperation?

R: Some say it's due to a characteristic of Libyan Jews. I find the problem among Israelis in general, even among the educated. If people do not see a budget in front of them, they are not willing to continue working on a problem. They are not even prepared to think together, to write a paper, to express an opinion, to explore, theoretically, what the best way is to approach a challenge or to overcome a gap. I know only of a few people who continue to be close to me, to want me to keep up my commitment to the Libyan Jewish cause. The others wait on the sidelines to see what's going to happen next. They are ready to cooperate, but only at the last moment, not in a sustained manner.

H: How do you expect people to work without budgets?

R: Here I disagree with the ideas of other Libyan Jews, or maybe all Jews. No one shares with me the will to say "All right, let's carry the burden together," or "Let's do what's necessary, and later we'll see from where to get the money." Instead, they stop everything. They're willing to deal with a problem only if someone else, or another organization, provides the means.

H: How would you act in circumstances of a limited budget?

R: If you believe in something you have to be willing to invest money in it as well. If you don't have money, show your commitment by hard work and time. It's because of the lack of people ready to collaborate with me that I've changed my strategy by concentrating on occasional but highly visible events. I do not think the impact of these events disappears. When we cooperated with the exhibit in . . . [Bet Hatefutsoth], it struck roots upon which we which we could build. We have brought together Libyan families from Israel and Italy. Some of these affairs have attracted as many as 4,000 people; I am sure that some of the message is getting through. They received an injection of pride; they do not have to see their Libyan roots as some poor page in the book of Jewish history. Perhaps I have failed, but I believe that the message stays with people.

H: What keeps you working on this topic, even when you meet indifference in others?

R: The deep love of my mother for my father, and her continued devotion to him, was transferred, I feel, into feelings toward Jewish causes and towards Zionism. I believe that each Jewish community has to develop its own cultural assets. Its past should be made known to the young, to the young of all groups. This is the only way to develop a sense of kol yisrael ahim (all Israel are brothers). Each group has to know the other...Poles, Libyans, and so forth. That is the road to respect and the way to avoid misconceptions. We have to overcome prejudice so that one group won't think that it has come from royalty and is higher than the others.

In my activities, I have tried to give my community pride. I've helped them discover things that they don't know about their own past: information about their grandparents. Having this knowledge is one of the factors that can move people from passiveness to activity. Everyone has a role. People should be more than just "spectators," "guests" or "visitors." You have as much right to speak as other people. Libyan Jews in Israel did not acknowledge that they were Libyan. I have tried to give them "cultural capital."

H: How do you look back on what has been achieved so far with regard to Libyan Jewry?

R: I think that thus far I have accomplished two main things. First, is the fact I have organized the biggest projects ever concerning Libyan Jewry. I don't deny being proud about that. Secondly, I have implanted a certain amount of positive communal feeling and will to work among Libyan Jews. On the other hand, there is much that I have not achieved. There is still no sense of unity within Libyan Jewry, and I have not been able to motivate the most qualified people to cooperate.

H: Do you think this can yet be accomplished?

R: I am optimistic for two reasons. One is the interest I find in the young generation. They are more concerned about their heritage than I would have expected, and more interested than they were a number of years ago when I started my activities. Secondly, they don't have the negativism that I often found in the older generation.

H: You feel there is a new interest among younger Libyans in their history and heritage?

R: When I first started working on the topic of Libyan Jewry, the attitude was that we didn't want to be reminded of the past, which was an unhappy story. The Libyan Jews accepted the position of Ben-Gurion. He claimed that from the time the state was established there would be no more Sephardim and Ashkenazim, no Libyans or Poles, only 'am ha-yehudi, the Jewish People. I think, however, that his slogan was foolish, even though its aim was to create unity and to build loyalty to the medina (state). My belief is that the goals of unity and nation building are best achieved when each qehilla, each community, sees itself as a component of the mosaic. Then everyone can be proud to contribute his own special portion to the medina.

H: You mean everyone should make some contribution, even though they may be of different kinds and in different amounts.

R: The important thing is not to be a spectator. If you don't give something, say something, you are just a listener, only passive. By bringing something from your own past, you begin to react and be part of things.

H: So your interest in traditional Libyan culture, in the past, is oriented to the future.

R: I firmly believe that. I don't organize these events because I like to eat mafrum (a Friday night delicacy), or listen to the darbuka (drum). I don't like provincialism. It is distasteful to me just to focus on these bits of nostalgia.

H: On folklore?

R: I admire folklore when it is a channel for a deeper message. It can show what the meaning is of 2,000 years of history. For all that period the Jews of the Diaspora kept their culture and identity. Even when they imitated the Gentiles, or absorbed influences from other cultures, like the Islamic world, they did not lose their distinctiveness. I'm sure if these things were studied, you could find that Jews borrowed from other cultures, such as in their manner of dress, but other cultures also borrowed from the Jews.

H: Historians and anthropologists have, in fact, documented such processes.

R: Now, Israel is beginning to recognize the importance of different traditions and their contributions. The attempt to create a unified Jewish nation was, in fact, harmed by an overemphasis on the state. That was the dogma . . . of Ben-Gurion in the 1950s.

H: Don't you think there was some necessity in stressing to the

immigrants that they were now part of a new society?

R: It was understandable in the first ten years, right after the state was created, when people were in transit camps. People had to be weaned somewhat from their past and encouraged to learn modern ways. Otherwise today we would have the Casbah on the one hand, and ghettos of Poland for the Ashkenazim on the other.

H: What would be wrong with having a Polish way of life?

R: They preserved a ghetto style when they first came to Israel: their way of keeping shops, with a lot of rubbish and shmattes (rags). It was not at all modern.

H: What you say about the Ashkenazim is what many European Jews felt about the Sephardim. They were concerned that the Middle Eastern Jews would hold on to what they had, without being prepared to build a new society.

R: I see things differently. The Sephardim more easily followed the guidelines of the country's leaders except for . . . [nusach] in the synagogue. Within ten to fifteen years they absorbed much more of the new Sabra mentality. I mean by that, the Israeli way of life: a mix between Zionist dreams and the new political reality. They learned to operate in a new system based on democracy; they grasped the meaning of the vote.

H: Was this rapid absorption positive in your view?

R: Not in all instances. They also learned that one is free to have a mistress, to smoke on Shabbat, not to observe kashrut. There are some negative aspects to their new life in the medina.

H: I'm trying to reconcile the picture you portray with the common image of Sepharadim as a more traditional population.

R: In some ways, they are more conservative, particularly with regard to the synagogue or food. Perhaps, however, precisely because they could preserve their home life and internal customs they absorbed much more of the new Jewish society in Israel. I therefore think that Ben-Gurion was mistaken in trying to block attachment to their traditions.

H: Your work among Libyan Jews has been guided by the belief that people can both hold on to their traditions and change in ways that make them part of the new state.

R: My Libyan Jewish involvement is a natural part of my activities, but it also is consistent with my fundamental beliefs. The most efficacious way to build Zionism, with a sense of belonging on the part of each community, is to cultivate it with the sentiments of a family. If you are a strong and united mishpaha (family), everything is handled well. Every member of the Jewish People can meet around a big table—the medina. Everyone brings his own portion of culture or folklore. This is the way to construct an active and concrete Zionism, not just a set of principles.

H: How do you link this idea to classic Zionism?

R: Theodore Herzl, and that's all . . . . No one should be kept outside, just looking on. Every community has something of which it can be proud. Everyone is the holder of a title. Each group on its own is small, the Libyan Jewish people, the Polish Jewish people, but they are together in the medina. There, they can compete, each one trying to show his best pieces of art. I say to my Libyan friends, "take out what you own from under the sidda.30 Maybe you don't consider it valid, but let's polish it and present it."

H: Do you see that all the policies which directed the absorption of immigrants as misguided?

R: As I said, in the first generation it may have been necessary to discourage communities from sticking to their past, but that policy also had negative effects. It repressed innovation based on the histories of various Jewish groups. You can see that clearly in the system of education; the history and culture of the Jews of the Middle East were not introduced properly into the schools. No one was taught, for example, that Zionism existed among the Jews of Libya.

H: About thirteen years ago the government addressed this problem. There is now a whole division in the Ministry of Education devoted to integrating the topic of Middle Eastern Jewry, its history and culture, in the curriculum.

R: Yes, but that step reflected the growing political weight of Oriental Jews in the society. It did not stem from a true evaluation of the needs of the country by the people in power.

H: When immigrants began to arrive in the country, the policy was to encourage them to become Israelis as rapidly as possible. At the same time that there was an attempt to overcome ethnic differences, however, the newcomers were divided along new lines.

R: You mean politically, by the different parties.

H: That's right. The immigrants were enfranchised upon arrival. They immediately were given the right to vote, and the existing parties began to compete fiercely to attract them.

R: That was another policy that was exaggerated. It was correct to give people their democratic rights, but it kept Libyan Jews from working together on cultural matters that they shared in common. Political divisiveness still stands in our way today.

H: Was one of the reasons that people objected to your initiatives the fact that you were not identified as religious; you were not connected to the National Religious Party?

R: That was one of the reasons.

H: Are most Libyan Jews supporters of the National Religious Party?

R: Not at all. When I became more acceptable to the Mafdal (National Religious Party) people, by working with Ben-Zion Rubin, other problems [arose] or existed. Ma`arakh (Alignment)31 people claimed that I was in the hand of Benzy Rubin both when he was in Mafdal and when he moved to Tami.32 That's what I call the politicization of Libyan Jewry.

H: Which Libyan Jewish leader is linked to the Ma`arakh?

R: A man by the name of Avigdor Roqah. He heads something called the Libyan Jewish Association which initially was linked to Mapai.

H: You mean like the Va`ad Qehillot Luv was linked to the Po’el Mizrahi?

R: Yes, and there is still an ongoing clash with him.

H: How did the clash begin?

R: It had to do with WOJAC, the World Organization of Jews from Arab Countries. You know, the organization of which Mordechai Ben-Porat was one of the founders.

H: Ben-Porat who was a Member of Knesset and also served in the cabinet once?

R: Yes, he is originally from Iraq. Mordechai Ben Porat was working on forming a WOJAC executive committee. He wanted it to represent all the Jewish communities from Arab countries. He tried to avoid quarrels by choosing each member of the committee from some existing body. For example Shaul Ben-Simhon represented the Moroccans…[and] could bring the flag of an organization of the Moroccan Jews. Also, he was in the Histadrut, and supposedly brought the labor union's support for WOJAC's agenda. That method of forming the executive meant choosing only Israelis, not Jews from Arab countries who were living abroad. In that manner he selected Avigdor Roqah, from the Libyan Jewish Association.

H: You didn't feel that Roqah was the right person?

R: Some of the people Ben-Porat picked were weak; they had nothing to contribute. They were looking for additional positions and prestige. A number of them were clearly in political decline, and were trying to make a comeback. I challenged Ben-Porat with regard to his selection of Roqah.

H: And ever since then there has been tension between you.

R: Yes, but I tried to iron it out during Libyan Jewry week. Ben-Porat told me that he wanted me to make peace with Roqah. I said "No problem," I will invite him to be on the advisory committee.

H: Isn't it naive to expect that the Libyan Jews will be totally united?

R: I understand that in the 1950s they were pulled in different directions because of the struggle over their votes. Both Zuaretz and Roqah worked for their parties, trying to bring the Libyan vote. But now they can be more mature. People have their political differences but should be able to work together on matters of culture.

H: How do you evaluate the performance of Libyans who were elected to the Knesset and participated in the government?

R: Rabbi Frija Zuaretz was the first member of the Parliament from the Libyan community, representing the National Religious Party. The work he did in publishing books and pamphlets on Libyan Jews, and on our heritage, is very important. Afterwards there was Ben-Zion Khalfon, from Mapai. He died in a car accident after being the Deputy Minister of Agriculture.

H: Benzy Rubin was undoubtedly the most effective member of the community to serve in the government.

R: That's true. I didn't always agree with his role with regard to the Jews of Libya. He honestly fought for what he believed however. I think he was overly timid with regard to being a Libyan Jew who had a very important role in the medina.

H: You mean when was he was Deputy Minister of Labor and Welfare, as part of Tami.

R: That's when he was at his best. He managed the ministry very well, better than either Abuhatzeria or Uzzan could have done.

H: He is a very capable organizer.

R: The more means he has at his disposal, the better he works. He is less effective when he has to deal with smaller problems, such as the Jews of Libya.

H: The whole question of ethnicity in Israeli politics has always been problematic. On the one hand it was viewed as a taboo subject, threatening national unity, but, on the other hand it reemerges in various ways. The Tami party did not hold up long after its initial success, but now we have the growth of the Shas Party, which brings together Sephardic ethnicity with ultra-orthodoxy.

R: To my mind, we Jews from Arab countries have failed in our most important mission: to create a dialogue with the Arabs. Even if given a chance, our present leaders might not know how to seize the opportunity. They are limited to their involvements in Israeli politics, and have no larger vision. You can see this in the small fights of the Sephardi leaders, Nessim Gaon, Leon Tammam, and others.33 We have failed to present ourselves as a credible counterpart in the larger political arena.

H: Have you ever tried to encourage developments in this direction?

R: There was a period when [Anwar] Sadat was alive during which I started to play a role. I was invited to participate in a delegation of Sephardi leaders when Sadat came to Ben-Gurion University, in Beersheba. Nessim Gaon was there also. That was the first occasion on which the Sephardim could have begun to properly play their political role. But events deprived us of that opportunity.

H: Did you see Sadat as wanting to cast the Middle Eastern Jews in that role?

R: I am sure he did. On one occasion he gave the Sephardic [community] … permission to refurbish the synagogue in Cairo, and to put the Geniza in order.34 In my view that signaled the starting point of the role of the Sephardi [but]... political events ruined that chance as well.

H: To what extent do wealthy Sephardi leaders have the ear of powerful people in Israel?

R: These leaders do not have real power. They are used by the people with power.

H: When Ismar Schorsch, the Chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America was in Israel during the "who is a Jew” crisis, and was speaking to Shimon Peres, Peres stopped the conversation to answer a call from abroad from Nessim Gaon.

R: That is influence, but not power. Our leaders are used by those in power. Power means decision making, and you can make decisions when you are holding something, that someone else needs. Nessim Gaon and Leon Tamman are big donors to [both] Peres and [Yitzhak] Shamir. During the elections they contributed about 2‑300,000, perhaps half a million dollars.

H: Do they support both parties, or is there a leaning towards Peres?

R: Both parties, but I think you are right. In the last elections the big Sephardi donors were influenced by Steve Shalom,35 who leans towards the left and wants to support only Peres. He influenced Gaon to take a stand on that matter.

Still, they do not have power. Nessim Gaon, for example, gains satisfaction that Peres listens to him, or may even ask him for a recommendation, but the decisions are in Peres' hands.

H: Elections results still show that Israelis of Middle Eastern background tend to support the Likud.

R: That's true. The Sephardic leaders outside the country don't know how to use their influence on Israeli politics properly.

H: Which party would you support?

R: I don't like either of them.

H: Tell me more about WOJAC. It seems to me that the cause of the Jews from Arab countries has the potential of interesting many people.

R: We held an executive meeting of WOJAC during that [Anwar Sadat’s] visit because we wanted to try to show that we can create a dialogue between our group and the Egyptian government. The Israeli government had advised against WOJAC involvement. As usual, they exercised no imagination and didn't want to enlarge upon the subject, or to accord any value to our cause. They only wanted to introduce Sadat to a delegation of former Egyptian Jews, I proposed to the Executive of WOJAC that that they demand that there be a WOJAC delegation, not only an Egyptian delegation. I also wanted to be the head of the WOJAC committee because I saw it as a historic occasion. Never before had there been an opening to meet an Arab leader who could give us an official role and recognize the validity of our contributions as Jews during our sojourn in Arab countries. It would have been possible to build upon such an occasion. Sadat's statement could have molded opinion in other Arab countries, because of the spirit with which he came to Israel at that time. Despite my urging and insistence that a vote be taken, I was defeated. The WOJAC leaders did not want to upset the State of Israel, in particular [Menahem] Begin, by insisting that we see him [Sadat]. In my mind there was no setting better than that. And in fact we never got another opportunity.

H: Why did the Israeli government not want to give prominence to the issue of Jews from Arab countries?

R: They did not want to introduce subjects which were outside of the agenda of Israeli-Egyptian relationships. That is the mentality of Foreign Ministry bureaucrats. Perhaps, too, there was something political; they did not want to give a role to Ben-Porat. Basically, I think it stems from a lack of imagination.

H: Do you still see Middle Eastern Jews as having a special role vis-à-vis Arabs?

R: Ethnic groups will always have a role to play… I can illustrate this from my Libyan experience, which was similar to Egypt and other Arab countries. The importance of ethnic groups became apparent after a decade of the Libyans attempting to fill the vacuum left by the foreigners, particularly the Jews, the Greeks, the Italians, and so on. At first the Arabs were greedy to take possession of all the property left by those communities. That moment has passed, and today they realize that all what they achieved is negative. Now they miss the presence of non‑Arabs.

H: I’ve heard similar statements by some of my anthropologist friends who have spent time in Morocco.

R: You hear it everywhere. I see this attitude among the Sudanese, who are a people without hypocrisy. Without foreigners, particularly the Jews, life is not tasteful.

H: But will foreigners, especially Jews, ever return to these countries?

R: People say that one cannot turn back the clock of history, but I believe that it is possible, in certain ways.

H: Do you envision a mass migration of Jews back to North Africa?

R: Of course not. But I do think that we can continue to play our historic role in the context of Israel. As Jews from Arab countries we are still linked to a Middle Eastern heritage, but, transplanted to Israel, we are continually absorbing the experience of the West. Nevertheless, we remain Oriental. This gives us a certain capital, which world Jewry should learn how to exploit in the Middle East conflict.

H: Middle Eastern Jews have been in Israel, which was initially shaped by Europeans, for two generations, now. Do you really think they still have an Oriental quality to them?

R: Definitely. Their absorption and assimilation have only been partial. Even those who are Sabras, or are intermarried with an Ashkenazi, still have a big dose of Oriental character in them. And this gives us the chance for gluing together peaceful coexistence with the Arab countries.

H: You mean, for example, that they could get involved in business with Arab countries.

R: That's one of the practical sides of the issue, but there is also the question of basic principles. The Jews from Arab countries are the ones who convince the Arabs, in their own eyes, to accept Israel. The existence of this category of people proves to the Arabs that the Jews are entitled to have their own country and state. The Russian Jew is nothing to them; they view him as unconnected to the region.

The Oriental Jew provides a way for them to recognize two things. The first is the similarity between Arabs and Jews. They understand each other, speak the same language, and share the same mentality. Even in the realm of religion, they have many customs in common. Arabs naturally accept Middle Eastern Jews as interlocutors. They do not like to be forced to deal with "Motti Chaskelevitch," which they see as a "product of Europe."

H: Do you think the image of Israel as a socialist country is another factor that makes it seem “foreign" in Arab eyes?

R: Perhaps. The Middle Eastern Jews have a role to play in overcoming all those misperceptions.

H: What is the second thing that Arabs have to recognize?

R: Those are the practical matters: business and politics. The latter is very important. The potential contribution of Middle Eastern Jews has not yet been exploited, due to both objective circumstances and lack of imagination on the part of Jewish leadership.

H: I think you're right about "natural ties" between Jews and Arabs who share the same background. For close to ten years now Moroccan Jews who live in Israel, Moroccan Israelis that is, have been able to visit Morocco. I have heard from friends who visited there that some Muslim Moroccans, through these Israeli visitors, keep up with the lives of their ex‑neighbors who now live in Tel Aviv, Ashdod or wherever. They know that this one's daughter got married, and that another's son is in the university, and so forth. In a sense, they still consider these people their neighbors and follow what they are doing.

R: That's a small detail, but I think very significant. It shows that that the link is not a superficial one. If someone keeps up with all the everyday matters and wants to know: "How is Judith? Is she married, and how many children does she have?", or "What about Khlafu, what happened to him after his illness?", it's a clear demonstration that the sentiment continues to exist.

H: If these types of bonds were taken for granted in the past, how do you explain the prevailing sentiments of animosity and tension?

R: That is the challenge that our leaders have to face.

* Harvey E. Goldberg is Emeritus professor, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Sarah Allen Shaine Chair in Sociology and Anthropology, author, translator and editor of numerous books in Sephardic and Libyan Jewish studies: Jewish Life in Muslim Libya; Jewish Passages; DYNAMIC BELONGING Contemporary Jewish Collective Identities, Perspectives on Israeli Anthropology.

1 A picture of Raffaello's father is found in Raphael Patai

and E. Rosow. The Vanished Worlds of Jewry. New York: Macmillan,

1980, p. 122.

2 There are various estimates. Some think that by 1967 the number had reached 6,000.

3 Some features of this interaction are described in Harvey E, Goldberg, “Patronage as a Model for Muslim–Jewish Relations in North Africa: Contributions of Anthropological Field Research and a Case from Libya.” Intertwined Worlds, Special section of Religion Compass 6(2), 2012, pp. 152-62. DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2012.00337.x

4 Harvey E. Goldberg, "Gravesites and Memorials: Alternative Versions of the Sacralization of Space in Judaism.” In E. Ben-Ari and Y. Bilu, eds. Grasping Land: Space and Place in Israeli Discourse and Experience. Albany: SUNY Press, 1997, pp. 49-62.

5 The quotes in this section are from a series of interviews carried out in the summer of 1989, along with the extensive interview session transcribed below.

6 Abraham Karlikow was the representative of the American Jewish Committee to the Consultative Committee of Jewish Organizations that sought to ensure the rights of minorities while a Libyan constitution was being formulated under U.N. auspices.

7 Renzo De Felice, trans. Robert L. Miller, The Jews in Fascist Italy. A History. Enigma Books, 2001.

8 Renzo De Felice, Ebrei in un paese arabo: gli ebrei nella Libia contemporanea tra colonialismo, nazionalismo arabo e sionismo (1835–1970). Bologna: Mulino, 1978.

9 On Fellah’s activities in Rome, see Harvey E. Goldberg, “History and Experience: An Anthropologist among the Jews of Libya,” In J. Kugelmass, ed. Going Home. YIVO Annual 21:241-72, 1992.

10 Yehudim be-eretz aravit. Trans. Immanuel Hartom. Tel Aviv: Maariv, 1980, under the auspices of The Cultural Center of Libyan Jewry, with support of the Department for Sephardi Communities of the World Zionist Organization, The World Sephardi Federation, The World Organization of Jews for Arab Countries, The Center for the Integration of Sephardi Heritage in the Ministry of Education, and the World Jewish Congress.

11 Goldberg, “History and Experience”; idem, “ The notion of ‘Libyan Jewry’ and its cultural-historical complexity.” In Frédéric Abécassis, Karima Dirèche, and Rita Aouad, ed. La bienvenue et l’adieu: Migrants juifs et musulmans au Maghreb (XVe-XXe siècle), Volume 2: Ruptures et recompositions. Casablanca: Éditions La Croisée des Chemins, 2012, 121-134.

12 Frija Zuaretz, A. Guweta, Ts. Shaked, G. Arbib, F. Tayer, eds., Yahadut Luv. Tel Aviv: Committee of Libyan Jewish Communities in Israel, 1960.

13 Pierra Rosetto, "Displaying Relational Memory: Notes on Museums and Heritage Centres of the Libyan Jewish Community." In Dario Miccoli, Emanuela Trevisan Semi, and Tudor Parfitt, eds. Memory and Ethnicity: Ethnic Museums in Israel and the Diaspora. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 2013, pp. 77-95.

14 On this Heritage Center see: https://www.bjhcenglish.com/. Its development was spearheaded by Mordecai Ben-Porat, who is mentioned in the interview with Raffaello.

15 The pilgrim visit is described in Maurice M. Roumani, The Jews of Libya: Coexistence, Persecution, Resettlement. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2008, pp. 217-220. In his opening remarks on the events, Roumani notes that “some call it bizarre.”

16 It is possible that through back-channel communication, some Israeli leaders knew that Qadhafi was considering moves in this direction (see Roumani, Jews of Libya, p. 217), but not necessarily details of a planned visit.

17 Maurice Roumani was among those present at Rafah. I had the chance to observe interactions between the visiting and Israeli Libyans at the Hyatt Hotel.

18 This is only a hunch on my part without direct evidence, but this sharp remark might have reflected a dictate by the US to react negatively to the Libyan initiative, which it viewed as attempting to weaken the grip of the UN sanctions. The Israeli Deputy Foreign Minister at the time was Yossi Beilin who during the very same year was involved in the secret negotiations with Palestinians that led to the Oslo Accords.

19 The English translation of the book was: Jews in an Arab Land: Libya, 1835‑1970, trans. Judith Roumani. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985.

20 See De Felice, Jews in an Arab Land, pp. 192-210; Harvey E. Goldberg, Jewish Life in Muslim Libya: Rivals and Relatives. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990, pp. 197-222; Roumani, Jews of Libya, pp. 48-56.

21 See Roberto Nunes-Vais, Reminiscenze Tripoline. N.p.: Edizioni Uaddan, 1982.

22 On Abraham Karlikow see note 6 above. He reconnected to Libyan Jews in Rome, including Raffaello, in the late 1960s.

23 Eliaho (Lillo) Arbib was born at the time of the Italian conquest of Tripoli (1911), received an Italian education, and was trained as an accountant. In 1948 he was appointed by the British to head the Jewish community in Libya, and was among those remaining after independence. His personal letters to officials in 1967, after the violence that broke out in Tripoli in wake of the 1967 (Six-Day) war, were critical in moving the government to allow Jews to emigrate. The book to which Raffaello referred probably is Gli Ebrei in Libia fra Idris e Ghedadafi, 1948-1970: pagina di storia contemporanea. Tiratura speciale per il 2º Convegno Internazionale degli Ebrei di Libia. Roma, 19-22 gennaio 1989. Arbib died in 2003. See the online article in Haaretz: https://www.haaretz.co.il/misc/1.906323, accessed 11 November, 2019. In 2018, his sons contributed Lillo Arbib’s archive to the World Organization of Libyan Jews in Or Yehuda.

24 The Knesset website with information on Zuaretz

25 Ben-Zion Rubin, who was a Knesset Member in the National Religious Party, and then one of the leaders of the breakaway Tami party. See Wikipedia: Ben-Zion_Rubin, accessed 11 November 2011. Rubin published a book in which he edited three diaries related to Zionist activities in Libya. Two were diaries of emissaries from Mandate Palestine in the years leading up to Israel’s independence, and the third—the diary of a local activist, Yosef Guweta. See Ben-Zion Rubin, Luv: Hedim min ha-yoman. Jerusalem: Ha-agudah le-moreshet yahadut luv be-shituf im ha-merkaz ha-tarbuti le-yahadut luv, 1988.

26 In a source cited by De Felice, Jews in an Arab Land, p. 198, he is mentioned as Major Arkin. In the diary of Ephraim Urbach he is referred to as captain. See E. E. Urbach, War Journals: Diary of a Jewish Chaplain from Eretz Israel in the British Army, 1942-1944. Tel Aviv: MOD Publishing House, p. 117 and passim. Neither source provides his personal name. (Hebrew).

27 See Mordekhai Hakohen, The Book of Mordechai: A Study of the Jews of Libya, translator and editor, Harvey E. Goldberg. London: Darf, 1993, p. 13.

28 A colleague of Rabbi Zuaretz who worked together with him on many of the publication projects of the Committee of Libyan Jews in Israel.

29 Haim Khalfon, Lanu u-levanenu. Netanya, 1986. The author’s father, in Tripoli, served as the secretary of the rabbinical court.

30 An elevated wooden platform, in a traditional Jewish house in Tripoli, that served as a bedroom for a family.

31 The Ma’arakh emerged-as a result of a merger from the historic Mapai party and eventually evolved into the current Labor party.

32 Tami is an acronym for the “Movement for the Heritage of Israel” that broke away from the Mafdal before the 1981 elections and gained three seats in the Knesset. It was headed by Aharon Abuhatzira, scion of a famous rabbinic family in Morocco. The other two Knesset Members were Aharon Uzan, from Tunisia, who had served as Minister of Agriculture as part of Mapai and Ben-Zion Rubin, from Libya, who also had been in the Mafdal. Abuhatzira was appointed Minister of Labor and Social Welfare, but resigned in April 1982 after being convicted of larceny. The Ministry was then run by Ben-Zion Rubin, formally in the position of Deputy Minister.

33 Nessim Gaon, born in the Sudan (1922), was a wealthy businessman and philanthropist who, beginning in 1973, was head of the World Sephardi Federation for many years. Leon Tamman was somewhat younger, and Gaon’s brother-in-law, and also widely involved in Jewish philanthropic projects. Both left the Sudan in 1956 and took up residence in Switzerland.

34 An extensive collection of manuscript fragments in Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic from the Middle Ages that were kept in the geniza—synagogue storeroom—of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fustat (Old Cairo). A good overview of its 'discovery' and significance is found in Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole, Sacred Trash: The Lost and Found World of the Cairo Geniza. New York: Schocken, 2011.

35 Founder of the American Sephardi Federation.