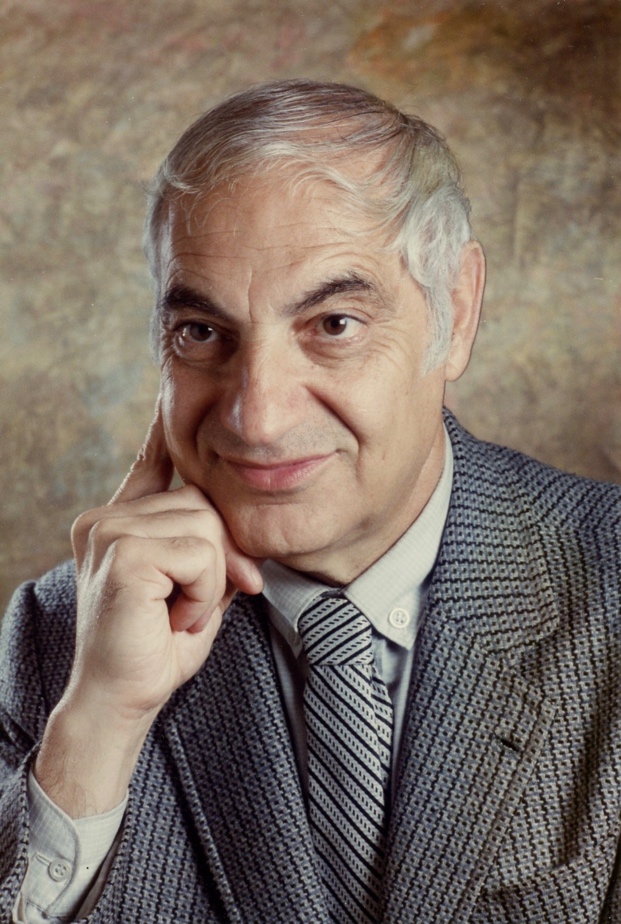

Habib Gerez: Humanist, Artist, and Poet

By Isaac Jack Lévy*

In the summer of 1990, during a visit to Istanbul to pursue our research on the historical and literary background of the Jewish community, my wife Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt and I stopped by the Office of David Asseo, the Haham Bashi (Chief Rabbi) of Turkey from 1961 until his death in 2002. By chance, we met Habib Gerez (Josef Habib Gerez), a native of Istanbul, born on June 14, 1926, in the suburb of Ortaköy, who was working as the secretary of the Haham Bashi. We spoke in Judeo-Spanish with some individuals present in the lobby of the Chief Rabbinate who spoke highly of Habib.

A close acquaintance said, “Gerez was highly renowned in Turkey and Europe.” One person referred to him as a humanist: “Even though he is devoted to his people, Habib does not differentiate a Jew from a Muslim or any other human being. For him we are all equal and should be respected as such.” Similar thoughts were expressed by the artist, Ester Almelek, an old friend who knew him for 50 years:

Gerez’s buddies, much like his persona, comprise a colorful spectrum. Those who know him well say he associates with all kinds of people, irrespective of religion or profession. He is kind and generous to his fellow writers, artists, and über-intellectuals.

Another individual present in the office interrupted, “Habib is a devout Sephardi interested in the future of his coreligionists and community.”

We learned that he was a passionate Turkish nationalist. One of his aspirations was for his people to feel Turkish and to speak and write in Turkish. As Beki Louisa Bahar, an 84-year-old Jewish poet and playwright in Istanbul and dear friend of Habib, observed:

Writers want to be Turkish writers, national writers, they don’t want to be Jewish writers. [Turkey] is not a country where, even if he is very successful, a Jewish writer is accepted. All our writers want to prove that they are Turkish.1

Sara S. Jamshidi interviewed Gerez in December 2015. “How do you get along with Muslims here?” she asked. Habib replied, “I am a Turk, only a Jewish one.”2

An acquaintance of mine from Istanbul told me, “For Gerez, there is nothing that he would not do for others: ‘Demanda i na, lo azi’ (Ask. There! It is done).’” Another person, who was present at the Chief Rabbinate, was totally in accord, “Mas devuada persona no ay (There isn't a more devoted individual).” Commentators and acquaintances have portrayed Gerez as a delightful and “magically engaging person, as well as a surprisingly likable” individual. Still they depict him as “overwhelmingly eccentric and a [charming] narcissist,” who “never failed to repeat his name more than one thousand times during our one hour tour [of his house].”3

Perhaps he acts thus with strangers. The experience Rosemary and I had was quite the opposite. Gerez is not one who demands the attention and admiration of others, not one who is more interested in the self, and is not jealous of those who receive any recognition. This is not the Gerez that we have come to know. There was nothing “surprising” nor “magical” about him. In our two meetings, especially the second one in 1997, and in our following emails and telephone conversations, I found him to be approachable, polite, and not at all pompous. On October 25, 2018, Naim Avigdor Gūleryūz responded to my email of October 13:

Concerning Gerez, I have known him since 1951/52, when we were attending the same class at the Law Faculty / University of Istanbul [which he did not complete because of health problems]. As far as I remember it was then that he published his first poems and he was very proud of them. He published several books of poems before he ‘appeared’ as a painter. I really don't know which part of his art prevails for him: the poetry or the painting . . . He was and still is a nice guy . . . He worked for the community since his young age: as a volunteer, assisting the orphans at the Ortaköy Jewish Orphanage in their lessons; as a member of different Jewish charities and/or cultural associations; . . . by writing articles in the Jewish press . . . and later as the private secretary of the Chief Rabbi. I do not have the impression that he ever hid his Jewishness.4

Insofar as Gerez’s connection to Judaism is concerned, some commentators, such as Jasmine Dilmanian, have an opposite view, “He is cunningly selective in terms of what he chooses to reveal about his past—and his Jewish identity is among the parts of his biography that he masks . . . Gerez does not identify with his faith, describing himself as an atheist . . . Entrenched in an odd state of apathy for a Jew raised in a Muslim state, Gerez denies any particular solidarity to the state of Israel.”5 She cannot provide any explanation for his connection with the Jewish community, two Jewish journals, his pride in being listed in the Encyclopedia Judaica, and “the large painting bearing the Star of David and other Jewish symbols occupying a wall in his bedroom [which] symbolizes a nation that raised [itself] from blood and dirt—Israel.”6

Carol Stevens Yūrūr writes that Gerez “sees himself as an international artist in the humanist tradition. ‘We are of the world,’ he said. ‘I do not believe in borders’.” Yūrūr remarks that “Gerez may not be a regular synagogue goer”7 and adds in another article that “many Istanbul Jews are not regular temple-goers.”8 While Gerez and his coreligionists consider themselves Turkish citizens, this in no way precludes them from being faithful to Judaism. From my own experiences, I will add, identity is flexible according to context. When I lived in Italy as a young boy, I considered myself Italian, but I still was a strong Jew; now in the United States, I consider myself an American and I still identify as a Jew.

During one of my earlier trips to Turkey, Beki and Mony Bardavid invited me to a Shabbat dinner. The apartment was full of people discussing several issues, among them life in Israel, the customs of the Spanish Jews, and humor. I brought up the name of Habib Gerez. A close friend of Habib described him as a man with many skills. “Habib Gerez is our pride. In addition to serving well the Chief Rabbi and the Jewish community, he is a poet, a painter, a journalist, a writer, and a teacher. He is fluent in many languages.”

In a subsequent trip to Istanbul, I visited Gerez. Seeing the abundance of works scattered all over the house, I asked him, “How many works have you done, how many have you published?” He replied, “No se, eskrivi un mabul de artikulos en jurnales, diarios, livros. No se” (I don’t know, I wrote a great deal of articles in newspapers, review magazines, and books. I don’t know).” When Naim Gūleryūz asked Gerez how he learned French, Italian, Spanish, Turkish, Judeo-Spanish, and to some extent, Hebrew and Russian, Gerez replied in French, “Autodidacte” (Self-taught).

When I asked him about his many accolades, Gerez gave me a copy of an interview in which he declared the reason for his international fame:

Fin oy en la Turkiya (onde bivo) i en otros payizes ize munchas ekspozisiones i partisipi en munchos konkorsos i resivi munchos premios por razon ke mis pinturas i mi teknika son diferentes de los otros. [En kuanto a la] poezia, resivi premios en los dos domenios. Es por esta razon ke el numero de mis premios son elevados.

(Up to today, in Turkey—where I live— and in other countries, I put many exhibitions and participated in many contests. I was awarded many prizes because my paintings and my technique are different from other painters. In so far as the poetry is concerned, I received prizes in both areas. As a result, the number of my prizes is high.)9

Due to his artistic and literary successes, Gerez attained international fame. He had over 150 exhibitions of his paintings in France, Belgium, the United States, Israel, Italy, and especially in Turkey. He won more than sixty prizes for his writing, including the Academia Internazionale di San Marco Poetry Prize in 1979, 1985, and 1993; the European Grand Prize on June 28, 1998; and the Academy of Europe’s 1991 Grand Prix de la Mediterranée Étoiles d’Europe. He was honored by several academies in Europe and Turkey, and among other honors, he was a member of the Association of the Turkish Press and the International Federation of Journalists and Writers. Moreover, Gerez is the recipient of numerous trophies, ribbons, and gold medals, which he displays in a case in his home.

During our 1997 trip to Istanbul, Habib invited Rosemary and me to visit his multilevel house, a true library with over four thousand as-yet-unsold paintings and poetry books. After briefly going over my literary interests, we went out for lunch, and visited a few Jewish buildings in the neighborhood of Ortaköy. Upon returning, I asked if he had any artistic interest in the Holocaust. Thoughtfully he replied:

Mancha preta del Olokausto fue

una para la istoria. Devemos siempre pensar en esta trajedia, pensar en

esta mancha i saver lo ke paso en Varsovia i en otros kampos donde

murieron miles, donde tantos fueron sakrifikados por ser djudios.

Korajozos djudios i otros puevlos fueron kemados en los ornos. Espero ke

esta trajedia no va pasar otra ves.

(The Holocaust was a dark stain

in history. We always have to think about this tragedy, to think about

this stain and know what happened in Warsaw and in the other camps where

thousands died, where so many were sacrificed for being Jews. Brave Jews

and other people were burned in the ovens. I hope this tragedy will not

happen again.)

We asked to see some of his work which was scattered all over the house and went over some of his artwork and books on poetry. Habib gave me several books. I asked him again if he had worked on the Holocaust. “Indeed, I did,” he replied. “I have several paintings and sketches.” Realizing that I was working on the Sephardic art of the Holocaust, he handed me several slides. After I returned home, he sent me printed copies of his pictures with titles and explanations.

During our October 2018, telephone conversation, I asked him if he had published or exhibited any of the Holocaust material. “I did not do much with it. I did not write about it nor exhibited any of it,” he replied. “It was not published anywhere. I wanted to show it to the public, but the galleries did not accept this kind of art. It could not have been done in Turkey. This topic is not interesting to the Turkish people. They are not interested in other people, surely not on the Holocaust.”

Therefore, I am presenting some of Habib Gerez’s paintings on the Holocaust, which he shared with me.

1. Concentration Camp with guard in front

2. Extermination Camp, Austria

3. Faces of the victims, living and dead, walking

4. Untitled. The Devil represents the Nazi Party; the Swastika represents German desire to destroy Judaism; the dead victims are piled on top of the Yellow Star of David

When I asked Gerez if he had written poetry on the Holocaust, he forgot that he had published a few poems on the tragedy. I conclude with two of these. “The Chimneys of the Ovens” depicts the horrors of the journey and of the camps.10

The Chimneys of the Ovens

With full cars

whole convoys

of innocent people

unaware of their destiny

go toward the fields of death . . .

In the sunken eyes

One can guess the horror and fright . . .

From the chimneys of the ovens

All hopes fade . . .

How much sadness

Turn it off in an instant

Of that sun born to shine,

Turned off for eternity

Become ashes,

The dying of white clouds

In the blue sky

Of the calm or wavy seas

Of the songs of the hymns to life . . .

In the sunken eyes

The horror is frightening . . .

From the chimneys of the oven

All hopes fade . . .

Habib Gerez conveys his despair in the following untitled poem:

My head is spinning

With all that happens.

Stop the world

Exit please . . .11

Habib’s final observation of despair is “We have devoured one another.”12 The indescribable pains suffered extend beyond words. According to Gerez they are personal, “They cannot be shared / they cannot be shared.”13

Habib Gerez speaks to us then through his art and his poetry. He is a multilingual community leader who is a widely recognized artist and poet, and winner of many awards. In order to understand Habib Gerez and the acclaim accorded his works, one must recognize both the Turk and the Sephardi blended creatively in one extraordinary man.

* Isaac Jack Lévy passed away in January 2020, just as this article was going to press. May his memory be a blessing. Isaac Jack Lévy (MA Iowa, 1959; PhD University of Michigan, 1966) was Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Spanish Language and Literatures at the University of South Carolina. He is author of And the World Stood Silent: Sephardic Poetry of the Holocaust (1989,1999); Jewish Rhodes, A Lost Culture (1989); and co-author with Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt of Ritual Medical Lore of Sephardic Women: Sweetening the Spirits, Healing the Sick (2003). His most recent book, Sephardic Voices of the Holocaust: A Forgotten People, will be published by the University of Alabama Press. Spanish is rendered in Judeo-Spanish orthography, which differs from that of modern Spanish. All images are courtesy of Habib Gerez.

1 “Josef Habib Gerez: Landscape / Turkish Jewish Poet Istanbul Modern.”

2 Sara S. Jamshidi, “Habib Gerez, A Turkish Painter, Poet Charming Nacissit [sic],” Goltune News, Modest Fashion & Peace Journalism. December 17, 2015.

3 Sara S. Jamshidi, “Habib Gerez, A Turkish Painter,” Goltune News, Modest Fashion & Peace Journalism. December 17, 2015.

4 Naim Avigdor Gūleryūz, email dated October 8, 2018.

5 Jasmine Dilmanian, Tablet Magazine Book Revıews, “The Turkish Art of Love”, April 9, 2012. .

6 Dalmanian, “The Turkish Art of Love”, April 9, 2012.

7 Carol Stevens Yūrūr, “Humanist Habib Gerez Creates Impressions in Poetry and Painting,” in Habib Gerez, Beyoğlu, Istanbul, Tiryaki Yayinları, 2000, 105.

8 Carol Stevens Yūrūr, “The Spanish Jews’ 500 Years of Safe Haven in Turkey,” Hilton Turkey Magazine, 23, no. 91, 1992/3, 24.

9 Gerez sent me a copy of an interview given in Istanbul. Unfortunately, it does not mention the name of the interviewer nor the date.

10 Translated from Turkish to Italian by Luigi Sassi and into English by Isaac J. Lévy. A poem by a similar title, “Chimneys of Ovens,” is included in Gerez: Art is My Destiny, trans. Erdoğan Ağca (İstanbul: Doyuran Matbaası, 2000, 215. Ellipses in original.

11 “My Head is Spinning,” in Gerez: Art is My Destiny, 228.

12 “Vicoli Ciechi” (Blind Alleys), in Gerez: Via Delle Speranze, 2000, 142-43.

13 “These Pains Cannot be Shared,” in Gerez: Art is My Destiny, 210-11.