Three about Flory: Two films

and a children’s book

about ‘Nona’ Flory Jagoda

By Judith Cohen*

Like countless other people, I have long loved and admired Flory Jagoda, who went from recording “Songs of my Nona” – “Songs of my Grandmother” – to being, herself, the beloved and revered Nona. Whatever my comments about the three items under review, this remains constant.

I should make it clear that this is being written from more than one perspective: as an ethnomusicologist specialized in Sephardic music, and with extensive background in both Balkan music and medieval Iberian music; as a performer of all these and other traditions, and also as a long-time friend and colleague of Flory’s. She and I first met in 1983, when my Canadian Moroccan Sephardic ensemble “Gerineldo” opened for her first concert in Montreal. Flory asked me to join her with simple harmonies in “Una kandelika” and “Adio kerida.”1 Flory and I stayed in touch. After a 1993 concert in Toronto, she spent a few days at my house, I visited her whenever I was in Washington DC, and I was honored in 2014 to invite her to sing a guest song with me in a concert at the Bulgarian Embassy there.

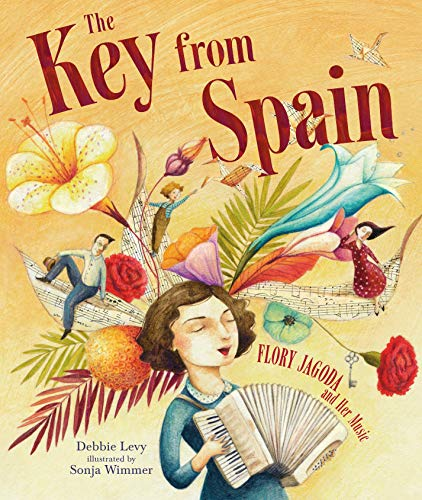

Book:

The Key from Spain: Flory Jagoda and her Music (Debbie Levy, illus. Sonja Wimmer. Minneapolis. Kar-Ben Publishing 2019. ISBN: 978-1541522190)

This is an illustrated book for children: quite young children, according to the author. It’s not an easy story to tell for children, as it includes the story of Flory’s family and the Holocaust. At the same time, it is notoriously difficult to avoid sentimental clichés, whether writing for adults or for children, and Levy has managed to avoid the temptation. I had already agreed to review the book for Sephardic Horizons when I remembered that the author had consulted me about some historical and musicological details two years ago, and was pleased to note that my corrections were incorporated. Basically, the author tells how Flory’s ancestors were forced to leave Spain, along with other Jews, during the time of the Spanish Inquisition, if they wanted to keep their religion. She sketches Flory’s early life in a small town near Sarajevo, and, later, as World War II became a dangerous reality, how playing her harmoniku (accordion), and singing songs in Croatian, not Ladino, so as not to reveal her Jewish identity, saved her. As a young bride, she began a new life in the United States. The old language kept by her family, now known as Ladino or Judeo-Spanish, her family’s songs, and her harmoniku also take on a new life, as Flory and her children sing the songs of her nona (grandmother), and her own new compositions . She herself becomes known as the nona, the grandmother, of Sephardic songs. The emblematic key so often evoked in stories of the Sephardic expulsion and diaspora becomes a metaphorical key, of music unlocking the door to a lost life. The story flows well, and reads quite engagingly; the illustrations complement the narrative and tone.

Films

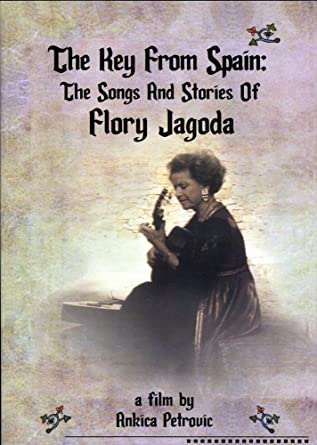

The Key from Spain.

Directed by Ankica Petrović and Mischa Livingstone. 2002. Distributed by

National Center for Jewish Film, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA 02454.

40 minutes.

Flory’s Flame:

the story of Sephardic music legend Flory Jagoda and her 90th birthday

celebration concert at the United States Library of Congress.

Directed by Curt Fissel, produced by Ellen Friedland, Jemglo 2014. 59 min.

These two films are twelve years apart, and quite different in style. The Key from Spain, released in 2002, lasts just over forty minutes. Ankica Petrović was clearly the obvious person to direct a film about Flory Jagoda. She is a Bosnian ethnomusicologist, whose work on both Bosnian traditions in general and Bosnian Sephardic music in particular I have been familiar with since the 1980s. Flory’s Flame lasts longer, close to an hour, and focuses more on the celebratory concert Flory performed at the Library of Congress for her 90th birthday, on September 21, 2013, with her family, friends and apprentices.

The Key from Spain (2002) gives a straightforward background account of Flory’s early life, and a capsule resumé of the history of the Jews in Bosnia-Hercegovina, from their arrival to the Holocaust, and, briefly, Flory’s return there many decades later. For the most part, Flory herself speaks, relaxed and informally dressed, sometimes in the company of her husband Harry Jagoda, who had recently passed away when the second film was made. After a list of scenes, Flory appears, wearing reading glasses, holding a tambourine, a scene echoed fleetingly with a page from the legendary medieval Spanish Sarajevo Haggadah, where Miriam is depicted also holding a tambourine. A few more illustrations from the same manuscript are lined up with following scenes, without labels or comments, as a subtle reminder of the continuity which Flory herself mentions often. In fact, she says that for her, the “only meaning” of the mythical “key from Spain” is “to continue, to go on.” Brief scenes of the Spanish towns of Hervás and Toledo (not identified by name, but familiar to me) lead to Flory’s discussion of Jewish life in Bosnia-Hercegovina. The Altarac2 (see pronunciation note below) family’s life in the small town of Vlasenica, her nona’s mastery of herbal remedies and her work as a midwife, and “the Altarac singing family,” are all vividly evoked. Flory emphasizes that her nona spoke only Judeo-Spanish; as was common, she called it ‘dzhidio’, i.e. ‘Jewish’, analogous to the Ashkenazi term ‘Yiddish’. Flory repeats her nona’s dictum: “sos dzhudia, kale avlar en dzhidio” (“you’re Jewish, you should speak Judeo-Spanish”).

Flory tells the story of her mother, Rosa, yearning for life in a bigger city, and eventually going to Sarajevo, where she married the musician Samuel Papo. Just a year later, Rosa returned to Vlasenica with Flory, then a baby, and created a scandal as the town’s first divorced Sephardic woman. Flory never did meet her biological father. Eventually Rosa married Mikhael Kabilio and moved with him to Zagreb, though for some time ‘Florica’ remained with her grandparents in Vlasenica. Flory recalls joining them in Zagreb; she didn’t really warm to her stepfather until the magic day when he took her to a music store after school and bought her an accordion. In April 1941, when she showed up for her weekly lesson wearing the obligatory yellow Jewish badge, her beloved accordion teacher told her not to come back. All these decades later, telling the story in the film, Flory has to swallow her tears and collect herself to go on.

She tells of how they left for Split: her parents sent her on a separate train with instructions to remove the yellow star, not speak, and play the accordion. This undoubtedly saved her, Flory explains, and goes on to recount how, when they were sent to the island of Korčula, she bartered playing and teaching the instrument for food and other necessities for the family. Fast forward to her marriage, in Bari, Italy, to the handsome young American Jewish soldier Harry Jagoda3; the news that all the rest of their family had perished – and her mother Rosa becoming “dead inside.” Forty-three years later, when Flory returned to Bosnia with Harry, they learned from a farmer that the whole family had been murdered, and were buried in a mass grave. That, and the destruction of the 1990s war in Bosnia, led Flory to compose her most somber songs.

In the late 1970s, the local Jewish Community Center asked her whether she knew any Sephardic songs, and – the rest is history, as they say. She ends the film singing a traditional welcome to the new week after the Sabbath, and speaks again of continuity and survival. Being Flory, she is serious and reflective, but also always positive and forward-looking, always embracing life and what it brings.

There are very few errors in the film. The narrator speaks of “the melodies of Spanish romansiero,” a common error. Aside from the spelling mistake (it is romancero, not romansiero), romancero refers to romances in general, or a specific corpus or anthology of romances, narrative ballads (not love songs, despite the popular misconception). No known Sephardic songs, including romances, use the same melodies sung in pre-expulsion Spain; in fact, there is no written record of Sephardic music of the time, although Iberian Jews probably did know many songs of their non-Jewish neighbours. Sephardim often sing an old romance’s story, but not its melody. In any case, Flory sings only one romance, “Anderleto” (known in ballad scholarship as “Landarico”), with a Bosnian melody; the rest of her repertoire consists of love songs, life and calendar cycle songs, as well as the songs she herself has composed over the years, many of which have entered the canon of the Sephardic song repertoire. So, for the most part, she does not sing melodies of the Spanish or even the Bosnian Judeo-Spanish romancero. Other than that, there are no inaccuracies in the film that I am aware of.

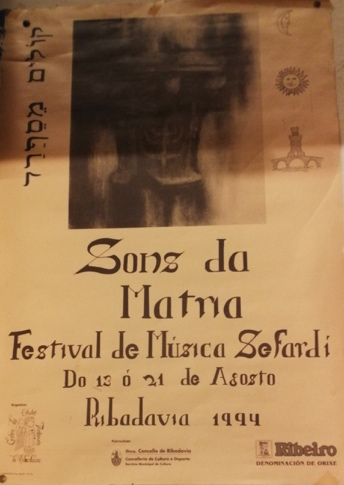

Poster advertising the 1994 Ribadavia festival, collection Judith Cohen.

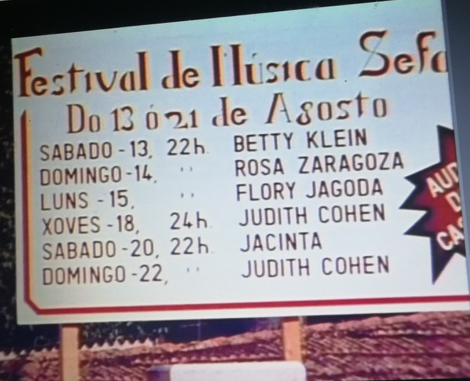

Toward the end of the film, Flory mentions two concerts which stand out in her memory: one in her home town of Vlasenica, and the other in Ribadavia, a small town in Galicia, northwestern Spain. On the program shown in the film (see photo), my name also appears, as I had been invited to both perform in it and be a music consultant for the project. This Ribadavia concert is also referred to at the beginning of the second film, Flame, albeit with two errors - not on Flory’s part: the year of the event, which was 1994, not 1995, and the statement “the king of Spain invited us.” The king of Spain had nothing to do with the invitation and was unlikely to even have known about it. The organizers were a group of friends in this small town, which has a long history of Jewish and then converso life. They decided to put on a festival of song and talks which they called “Sons de Matria” (“Sounds of the Motherland,” see poster). Having attended my concert of Sephardic songs nearby in 1993, they asked me to advise them about singers and speakers for this. The final line-up featured Flory and her family, Betty Klein from Israel, Rosa Zaragoza from Barcelona, Jacintha from France, and myself and my eight-year-old daughter Tamar from Canada, along with a few speakers. The organizers worked hard to obtain minimal funding; certainly the monarchy was not involved. It is a rather peculiar error, since, had the king invited Flory, there would have been considerable publicity, the performers would not have been billeted with the organizers, and there would have been at least one other concert, probably in the capital (and a performers’ fee).

Program from the 1994 Ribadavia festival, collection Judith Cohen.

There are other errors in Flame. Rather than take the opportunity to dispel romantic and inaccurate myths such as “preserved a repertoire of Jewish melodies that stretched back to the Golden Age of Spain” (Screenshot 2), the film’s narrative tends to reinforce them. There is no such thing officially as “the role of keeper of the flame”, much less a role “passed to” Flory or anyone else (Screenshot). The Jews of Spain did not, as written in one panel, speak “the Judeo-Spanish language known as Ladino,” much less with a ‘”Turkish” element, in pre-expulsion Spain. A quick consultation with a linguist working in Judeo-Spanish would have cleared that up, and provided a concise explanation of Ladino as a diaspora language, and its Iberian roots. In the credits, “Yo Parti Para La Gera” is credited as a “traditional Macedonian folk song,” but, like “Adio Kerida,” it is a widely-known Sephardic song; the latter is also not limited to Sarajevo. “Dieziocho Anyos Tengo,” similarly, is a Sephardic, not a “traditional Bulgarian folk” song. The orthography and the use of upper-case letters in the song titles might be attributed to Flory’s family tradition, though they could have been screened for consistency, and it would have been easy to add the missing accent over the “c” in Korčula, the island so important in Flory’s life.

While some might dismiss the errors as unimportant, or pedantic cavils, they are unfortunate because this film has a much wider circulation than the earlier one, aided by social media and other 21st-century forms of instant, widespread dissemination. Also, the concert which forms the centrepiece took place at the Library of Congress, and this, along with Flory’s justified fame and respect serves to reinforce the errors. In any case, romanticization is superfluous: Sephardic history, Bosnian history and Flory’s story are all more than sufficiently fascinating in their own right.

Screenshot from “Flame”.

Flory herself, direct and engaging as always, opens Flame by telling us “my nona would say if you cannot put your soul and your feeling into a song, don’t bother singing . . . and that is why most of the songs that I have written are a little bit too emotional sometimes, but that’s it, that’s what happens.” The phrase “she is the keeper of the flame” appears at the end of the first film (Key, at 37:08), and in the second film, her late son Elliot says “she is the ‘it’ of Sephardic music and the keeper of the flame; she’s made this happen.” Flory’s own narrative in this film is as compelling as in the earlier Key, including her moving return to Vlasenica, and her wedding dress made from parachutes. She uses a little more Serbo-Croatian in this later film than in The Key from Spain. Recounting the flight from Zagreb to Split in the train, she remembers her father cautioning her: “samo sviraj harmoniku I pjesme pjesme”-- “[don’t talk]; only play the accordion and sing songs.”

It is poignant to see footage of her son Elliot and husband Harry, who both passed away after the Library of Congress concert; the top line of the credits dedicates the film to their memory. Harry in the film is dancing with his walker, irresistibly irrepressible as always – I smile, recalling him. The only professional musician of the four children, Elliot recounts in Flame how at six he started noticing the musicians who came to their home, and hearing songs from different cultures, besides Ladino. Other family members, including Flory’s grand-daughter Ariel, who also sings and plays the guitar, as well as some close musical colleagues, add their observations.

Both films include several songs; in Flame, some appear in older footage of Flory and her family, and more in the live footage from the Library of Congress concert. It appears to have been a warm, engaging event, with Flory herself, her family, and musicians and singers she works with and has mentored. Several of the songs are performed by everyone, others by small groups or soloists. The atmosphere is celebratory and friendly, and everyone on stage is visibly happy and moved. At the time, Flory was already beginning to show some signs of memory lapse, which subsequently became serious. Although she was consulted throughout the preparation of the first film (Key), it is unclear whether she ever saw this second one (Flame) in its entirety before it was released.

With Flory at her home, 2016.

It is interesting to compare earlier interviews with Flory. I conducted one with her for my post-doctoral research in the early 1990s, when she was 68, and in 1995 the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC (USHMM) conducted a lengthy one (the online reference is below4; note that the transcription is full of errors). In the interview with me, Flory speaks of singing with her family, and specifies that “the harmonies were just a third up or down, or a fifth.” That is, they were not singing the oldest style of Bosnian songs, but rather a style which became popular in former Yugoslavia in the late nineteenth/early twentieth century.

To my knowledge, there has not been any scholarly study of Flory Jagoda in the fields of Sephardic studies and ethnomusicology. Mark Slobin dedicates a few pages to her in the context of a chapter on Eastern Europe in a late 1990s ethnomusicology textbook, and she is mentioned elsewhere, here and there; the USHMM interview also contains some material, sometimes quite serious, not in the films. Perhaps it is time for a scholarly monograph. Meanwhile, both films and the children’s book, the always appealing songs and Flory’s own addictive charm should keep her many fans happy.

* Judith Cohen (www.judithcohen.ca) is a Canadian ethnomusicologist, singer, medievalist and educator. She specializes in Sephardic music and related traditions, including music among the Crypto-Jews of Portugal, and music traditions of Spain, Portugal, the Balkans, French Canada, pan-European balladry, as well as in medieval music. She teaches part-time at York University in Toronto and is the editor/consultant for the Alan Lomax Spain collection.

1 After the concert, I heard her speaking Serbo-Croatian to a small, vivacious older lady, and introduced myself in my halting version of the language. Flory’s long-lost friend turned out to be Nina Šalom Vučković, whom I later interviewed and wrote about; she was the only Bosnian Sephardic woman to live the second half of her life on a Mohawk First Nations reserve.

2 The intervocalic “c” or final “c” following a vowel in conventional transliteration from the Cyrillic alphabet is used to indicate the “ts” or “tz” sound in English. Hence, Flory as a child was known as Florica, pronounced Floritsa. Her family name, Altarac, is pronounced Altaratz (sometimes written in English as Altaras), and her home town is pronounced Vlasenitsa. “C” as “č” and “ć” are pronounced slightly differently, but for general purposes may both be pronounced as English “ch” as in “church,” hence Korčula, Korchula; Ankica Petrović, Ankitsa Petrovich; and Nina Šalom Vučković, Nina Shalom Vuchkovich.

3 Sephardic Horizons has featured a poem about their marriage, accompanied by their wedding photo, “The Girl whose Dress was a Parachute,” by David Almaleck Wolinsky, as well as an in-depth two-part interview by Rosine Nussenblatt, in Sephardic Horizons Volume 1, Issue 2 and Issue 4 (eds.)

4 USHMM material related to Flory Jagoda, including videotaped interviews. Accessed January 28, 2020.