Tales of Seha the Sage and Seha the Clown:

Jewish Folktales from Morocco

By Marc Eliany*

Tales about Seha the sage and Seha the clown were widespread in Morocco and in all likelihood in the rest of the Maghreb, including Western Libya, as well as other Arab and Muslim countries in the Middle East.

Seha was everything to everyone in Morocco. Seha could be the smartest man on earth in one tale and the dumbest in another. Seha could be the poorest of all men in some circumstances and yet an advisor to kings in others. He was a child, a man, an angel, and a jinn too, a mythical ‘underground’ creature. He may have taken names such as Moha or Joha, yet he remained the same perennial clown. Seha offered storytellers in Morocco, among other places, an opportunity to make fun of everyone and everything without offending anyone.

Tales of Seha were in all likelihood influenced by Arab and Muslim mythology, which perceive Seha as an intelligent spirit, but of lower rank than that of angels. Seha shared some characteristics with the jinns, which were believed to be able to appear in human and animal forms, as well as possess extraordinary powers.

Jews and Muslim recounted Seha tales, coloring them with their own world of concepts from Judaism and Islam.

Granpa Elkhiany

Tales of Seha the Sage

I grew up under the wings of my paternal grandfather, Mordekhay Elkhiany, who acquired most of his rabbinical education under the auspices of the well-known AviHatsira family. My paternal grandfather was a devout man of profound Jewish knowledge. He read Torah, Talmud, and Harif’s HaHalakhot on normal days, and opted for the Zohar, the Book of Splendor, in times of mourning. I learnt from him to distinguish between עיקר and טפל, separating the important from the trivial, as demonstrated by ‘Harif’, Rabbi Itshak HaCohen of Fez, who drew the main Halakhot, i.e., key rules, from Talmudic debates, setting aside legends, and myths. My paternal grandfather conveyed to me the essence of Biblical tales, in a beautiful Biblical Hebrew and Jewish Moroccan Arabic, always stressing the ethical significance underlying the storytelling. My paternal grandfather’s Seha tales were colored by Jewish myths, as told in the tale “Amulets and Good Fortune,” where creation, Adam and Eve, and loving angels feature.

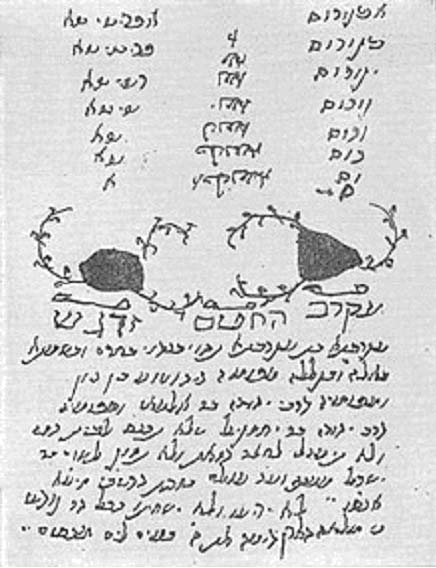

Moroccan Hebrew talisman

Amulets and Good Fortune

In the beginning angels disagreed about the creation of Adam and Eve. Some angels loved them, while others envied them. The angels of envy did everything in their power to undermine the first man and woman ever created and tempted them to eat from the Fruit of Knowledge. But eating the Fruit of Knowledge was forbidden and as a consequence, humankind nowadays must work to make a living. Some do well but many don't.

Angels of envy watch from above and say:“See, Adam and Eve lost Paradise. Now they will lose Justice too!”

But the angels who love mankind know the angels of envy well and from time to time they descend to earth to correct every wrongdoing.

One day Raphael, one of the loving angels, watched Seha working day and night yet hardly making a living. Raphael gave Seha wealth to make his life easier. But angels of envy came down to earth as crooks, to swindle Seha, and make his life miserable again. So Raphael visited Seha in his dream and gave him a good fortune amulet. The amulet contained nothing, but it made Seha's life on earth much easier!

Love and Compassion

My maternal grandmother, Tany Khessous, who was a seamstress of the Glaoui, the governor of Marrakech, was pretty familiar with political intrigues. Her tale of “Love and Compassion,” relating to Seha, was in all likelihood influenced by gossip about historical realities in Morocco, i.e., political instability and conspiracies, which often led to executions of innocent people. Jewish Moroccan influential leaders were indeed subject to such misjudgments. This kind of storytelling or mythmaking appears to provide socio-psychological comfort to a disadvantaged community, unable to fend for itself in a ‘dhimma’ system, where a saint or a mythical Seha, fulfills the function of a miracle-maker.

In the time of King Ishmael Al Alaoui (1672-1727), Moshe Ben Atar represented the king in foreign lands in commerce and diplomatic missions and to buy arms to maintain order in Morocco during times of rebellion (times of Siba). But in spite of the contributions Jews made to the well-being of Morocco, they remained subject to humiliation, as Muslim ministers became envious of Moshe Ben Atar because of his influence on the king. So they conspired to bring about his dismissal, imprisonment, and death. But kings did not need excuses to get rid of Jewish leaders in their service. They dismissed Jewish advisors to disinherit them on a regular basis. When Moshe Ben Atar died, his son-in-law left Meknes for Sla, near Rabat. He earned a living in gold and silver embroidery, while continuing his rabbinical occupations.

My maternal grandmother, the seamstress of the Glaoui, specialized in gold and silver embroidery, a specialization of Cohanim (i.e, priests) since antiquity. It is interesting to note here, that my maternal grandmother, whose family name was Khesus, considered herself a descendent of the priesthood, and that her family name was changed from Cohen to De Jesus in the forced conversion in Portugal in 1497. The name change from Jesus to Khesus and Khessous to Kesus occurred in all likelihood due to linguistic differences between Spanish/Portuguese, Arabic, and French influence.

Love and Compassion Tale

It was a time of great instability in the Land of Maghreb. The king ruled in the city while the opposition's control over the outskirts increased day by day. And rumors spread that Seha, the prime minister, had conspired with his father-in-law, the head of treasury, to get rid of the king and re-establish order in the country.

As usual in such cases, arrests followed rumors and the death penalty was certain to come thereafter. But Seha had a loving wife and as soon as the arrests took place, she rushed to the king to plead on behalf of her father and husband.

“My husband and father are innocent,” Seha's wife said. “Rest assured, compassionate king, my husband and father remain your loyal servants. The plot is for sure a fabrication to undermine your government.”

“There must be some truth to the rumors,” replied the king. “At least one man must be guilty, your father or your husband. Who shall I spare?”

“Spare my father, O compassionate king, a father cannot be replaced. As to my husband, though I love him dearly and he remains innocent, I could always wed a new one!”

Convinced, the king said: “Your love for your father equals your husband's innocence; their lives shall be spared for your sake.”

Ever since, it has been known in the Land of Maghreb that love breeds compassion, and royal misjudgments bring about the downfall of loyal servants.

Magic Cures and National Fame

The tale “Magic Cures and National Fame” points to the exposure of Moroccan Jewry to modernity, involving French education, migration from the outskirts to urban centers, as well as a rising awareness of the ineffectiveness of magic remedies. Interesting in this specific tale is the role reversal between a leader, i.e., the sheikh, and Seha, the commoner. The leader who may have ‘sold’ magic cures to simple folks is reciprocated by Seha, the simple villager, when he becomes more knowledgeable with the spread of education and urbanization.

In 1910, Morocco signed a Protectorate Treaty with France, allowing for a significant penetration of Western influence in Morocco. Moroccan Jews were subject to French influence somewhat earlier with the establishment of the ‘Alliance Schools’ around 1860. As the Alliance education system was financed primarily by the French government, it is proposed that Moroccan Jews were exposed to modern education to serve French interests to facilitate penetrating Morocco, as well as in response to the expressed aim of French Jews to benefit other Jews in North Africa and the Middle East. It is also proposed that French education served France’s later need to fill the demographic void left by population losses following World War I and World War II. The exposure of Moroccan Jewry to modernity is expressed in the following tale concerning migration from the outskirts to urban centers, as well as a rising awareness of the ineffectiveness of magic remedies.

Magic Cures and National Fame

Before French doctors brought us modern medicine, men and women had ancient cures for every ill in Morocco. It was a time when Seha was not a doctor but a very poor man in a very remote village in the Atlas Mountains. Poverty was not a problem because people knew how to live a simple life then. Yet Seha had a major problem. He had many daughters and the village became too small to find them all the right husbands.

Seha invested his savings in fancy cloths, moved to Marrakech, and told everyone he met he was a doctor of great fame. Soon people called upon him to cure every ill. He treated all his patients with great respect but gave them all the same medicine: sugar pills and enema. His basic assumption was that if his treatment did not help, it would not cause any harm either.

One day Seha was called upon to cure an aging sheikh. But as soon as Seha prescribed sugar pills and enema, the sheikh burst laughing. He remembered the formula for success he gave Seha some years before and felt better.

Tales of Seha the Clown

The tale of Seha the clown “Swimming with Stars” may appear different in its child-like simplicity. Yet it seems significant in pointing out an increasing migration from the interior to urban centers along the Atlantic and Mediterranean shores, stretching from Agadir and Mogador in the south, through Casablanca and Rabat in the center and Tangier up north, bridging the Atlantic and Mediterranean seas. Furthermore, it demonstrates the world of fantasy which occupied Moroccan minds since antiquity and expresses a wish to break out of land confines into the world beyond the Great Sea. Morocco was often referred to in rabbinical discourse as the ‘Land beyond which lies the Great Sea’.

Swimming with Stars

One warm night Seha went for a walk with his mother along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. The sea stood still and the moon and the stars reflected upon its face bright and clear.

“What is that?” asked Seha of his mother.

“That is the reflection of the moon and the stars upon the water,” replied Seha's mother.

“No” said Seha. “It cannot be. The moon and the stars must have gone for a swim.”

And hardly finished to express his point of view, Seha jumped into the water, to swim amongst the moon and the stars he liked so much.

Seha the Rain Maker

Jewish Moroccan tales are more characterized by saints’ tales, in which individuals’ and communal wishes are fulfilled, to save from pending disasters. Saints, and sometimes Seha, have the power to impact nature and change its course. They bring about storms of stones, ice, and rain to prevent harm to entire communities. They are able to summon darkness to save people from harm. They can stop the sun in its course to allow a saint to surrender his soul before Sabbath, to complete a funeral in due time, or to arrive home before dark. They can bring about a drought or rain following long droughts, as well as make rivers produce water in unlikely season. They can walk on water and transform matter, such as water into honey.

Seha is not a saint, but like a jinn who is an almost angel; he is elevated to the sainthood level in a humorous way, as he makes rain fall whenever he hangs cloths to dry.

Seha is a sage and a clown in Jewish Moroccan tales, combining Jewish, Arab/Berber, and Muslim mythology into one. Living side by side for centuries, Jewish, Arab, and Berber inhabitants of Morocco joined in the creation of a particular local culture in which pilgrimage, rites, myths, and tales combined in ways which express tolerance in good times (Dar Al Makhzen), as well as, hardship in turbulent transition periods (Dar A siba).

Seha the Rain Maker

Everyone knows that saints in Morocco were capable of bringing rain after long droughts. But few ever guessed Seha was able to make rain, too.

One day Seha traveled to a far-away village behind the Atlas Mountains to sell his wares. Upon arrival, he not only could not sell any of his merchandise, he also had to perform a miracle to save the poor villagers from thirst, as a drought of long duration dried every well and people had no water to drink.

As people were desperate, they asked Seha to make the wind bring clouds and rain. Seha asked the villagers to bring him a bucket of water, two sticks and, a rope. The villagers did as requested. Seha washed his cloths and hung them on the rope between the two sticks.

“What have you done?” cried the villagers. “The bucket of water we gave you was our last drinking reserve and you wasted it to wash your clothes?”

“Don't despair,” replied Seha. “Whenever I hang my cloths to dry, rain falls.”And as Seha completed his sentence, a strong wind brought clouds above the village and rain filled its wells again!

Moroccan Jews adopted not only tales but also local pilgrimage traditions. As my maternal grandmother conveyed in her tales, pilgrims plead saints to intercede on their behalf to have their wishes fulfilled: good health, a husband or a wife, fertility, a baby boy, a baby girl, good fortune, rain in season, abundant crops or a prosperous season in the markets. Later, I was impressed by the admiration of the Moroccan people to their kings, especially to the deceased Moulay Youssef. It often equals saintly reverence.

My painting, Pilgrims Hugging a Saint, 1993, portrays pilgrims’ reverence of saints and royalty. It expresses an ancient tradition of sleeping in proximity of saints’ tombs to benefit from their protection and blessings.

Pilgrims' wishes bring Moroccans together around the tombs of saints. There, salvation is sought, forgiveness is granted and promises are made. Carved on a tree or a rock are timeless wishes: a fish for fertility, a hand, an eye to guard against evil, red for sacrifice and green for abundance.

Pilgrims Hugging Saints, Marc Eliany, 1993

When pilgrims step on holy grounds, the presence of saints inhabits them, their hair stands on end, prayers and wishes come out of their mouths as if they knew them by heart from some old and ancient time. And when a bird flies over a tomb or when rain suddenly falls from above, pilgrims dance, as if chasing away spirits, and filled with joy, they chant:

"The saint is here!

The saint has come!

To bless

To cure,

Grant wishes, and

Hearts’ desires!"

Chasing Spirits, Marc Eliany, 1993

Exhibited at the Palais Clam-Gallas, Vienna, 1994

(sponsored by the Embassies of Morocco and France)

And pilgrims dip their hands in the saints' water and spread it on their eyes and lips and ears and every other part of their body craving for a cure. They go to their saints full of anxieties and leave happy and content that all their wishes will be fulfilled . . . Pilgrimage, contemporary psychologists might say, is in all likelihood one of the most rewarding therapies a Moroccan pilgrim could get.

* Marc Eliany (b. Morocco 1948) conducted national and international health surveys for Canada and the United Nations, where his publications are extensive. He documents the life and tales of Moroccan Jews in writings, paintings, video, and photography (www.artengine.ca/eliany/). He authored Like a King’s Daughter (Hebrew, 2012) and a Biographical Dictionary of Mediterranean Jews (French, 2001).