Being Sephardic, or Just Jewish?

Reframing The Study of Contemporary Ethno-Local Jewish Dimensions in Greece

By Maria Ch. Sidiropoulou1

Abstract:

The present qualitative and quantitative research highlights the contemporary ethno-local aspects of the Greek Jewish identity(-ies), that is Sephardic and Romaniote traditions, within the ever-changing world and more specifically, within the context of the secularized local Greek society. The religious identity of Greek Jewry, although referring to the acceptance of the Jewish religion (Orthodox Judaism) is presented theoretically as their basic coherent element; however, it has acquired another more cultural meaning in practice.

Through this empirical research, this article seeks to examine how the self-characterization of a person as a Jew currently living in Greece, is expressed, which ethno-local characteristics emerge, and how those are differentiated from generation to generation both within and outside the Jewish context and environment. For this research purpose, one hundred and fifty Jews (150) aged 18-75 years old from four different Greek towns (Athens, Thessaloniki, Larissa, Volos) were interviewed. The interviews were conducted during 2016-2017 in the largest Jewish communities in Greece (J.C.A., J.C.T., J.C.L., J.C.V.),2 located in the above cities.3

A. Introduction

For more than twenty centuries, the Greek peninsula constituted a refuge for the Jewish diaspora. During the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman periods, various Jewish groups made their homes there including: Romaniote Jews (316, 140 BCE) (Anastasopoulos 2015; Siobotis 2005; Luther 2004; Bickerman 1988); Ashkenazi(c) (1376, 1470 CE). From 1492 and onwards, large numbers of Spanish and Portuguese Jews (Varon Vassard 2018; Nar 2018; Altabé 2000) fleeing the Inquisition in the Iberian Peninsula, some of whom had stopped first in Italy (1536), were drawn to areas in the Ottoman Empire. A large population of Sephardi Jews settled in Thessaloniki and Sephardic creativity reached a high point in the sixteenth century. Since World War II and earlier, all Greek Jews have been slowly integrated into a single group, with the Sephardic characteristics ultimately prevailing while mingling with some Romaniote customs. The differences between the ethno-religious Jewish groups lie primarily in the different spoken Jewish idioms.

After the successive liberation of Greek territories from the Ottomans and their accession into the Greek state in the early twentieth century (1920-23), the identity of Jews living in Greece was redefined in relation to the rest of the Greeks, as it was institutionally recognized and bounded by the diptych: Hellenism and Jewishness (Hekimoglou 2016). Despite their long history and demographic superiority in the Greek context especially in Thessaloniki, in the mid-twentieth century, significant events such as the Second World War (1939-45) dramatically reduced their numerical strength (Hagouel 2013; Bowman 2002). Today, even with their small number in the total national population, the approximately four to five thousand Greek Jews retain Jewish identity through the secular, organization of their communal life, such as women’s activities with WIZO and AVIV in Athens and Ziv in Thessaloniki4 and Holocaust memorial events such as the Stolpersteine commemorations in the port of Thessaloniki and in the A' High School for Boys (Sidiropoulou 2020a & b; 2019; 2018a & b; Alcalay 2018). At the same time they have revived the ethnic and cultural aspects of their Sephardic and Romaniote heritage through religious, educational, or philanthropic activities and have fully complied with the Greek modern life model behaving as Greek Jewish citizens (Varon Vassard 2019; Sidiropoulou 2016; 2015a & b). Today, two synagogues function in the center of Athens, facing each other on Melidoni Street. “Etz Hayyim” Synagogue (1904), the older, Romaniote synagogue is referred to by the elderly as “the Gianniotiki.” The newer and larger Sephardic synagogue, Beth Shalom (1935), operates daily. At services in the synagogue, one will hear Judeo-Spanish and Romaniote melodies, with Greek words from Ioannina, where the largest Romaniote presence was located in the pre-war period. The Greco-Jewish (in Greek: γραικο-ιουδαϊκός/ή) dialect has many Hebrew/Jewish admixtures in terms referring to customs. Today’s Romaniote Jews follow the Sephardic ritual as theirs is no longer followed, except in a few “Zemirot” (hymns). In the Kiddush that follows the services in the community buildings, attendees eat foods from both traditions, such as “pasteles” (pies), eggs, and cooked greens. Romaniote and Sephardic recipes are now classified as a single culinary tradition although many Sephardic recipes retain their Ladino names.

This article is a sociological study of the contemporary national and religious identity(-ies) of Greek Jewry, both Sephardic and Romaniote, and how they interact within the framework of secularized Greek society.

B. Methodological Tools and Analysis

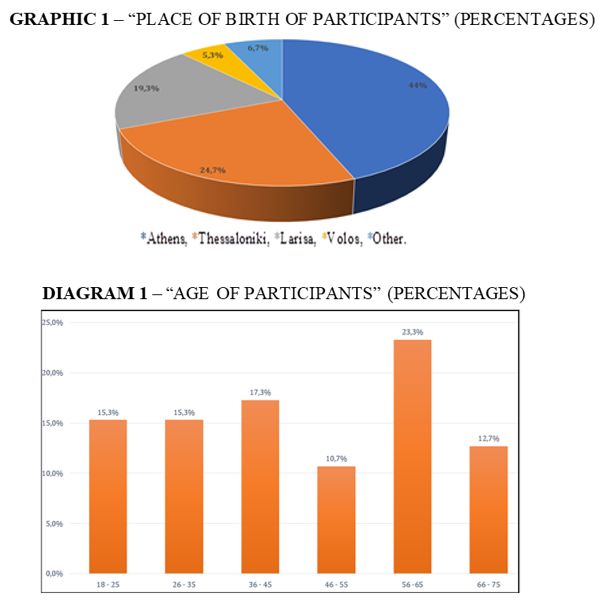

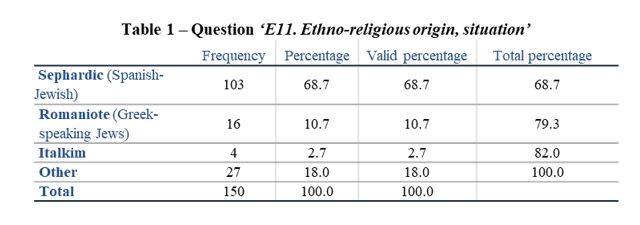

This survey is drawn from Ph.D. research that comprises qualitative and quantitative methods and on-the-spot observations in combination with an interview guide that includes both closed and open-ended questions. It was conducted between September 2016 and June 2017, in the following four Greek cities: Athens (49.3% J.C.A.), Thessaloniki (28.7% J.C.T.), Larissa (14.7% J.C.L.) and Volos (7.3% J.C.V.). One hundred and fifty people (52% women) participated in the study, the majority of whom were born in Athens (44%) and in Thessaloniki (24.7%) (see Graphic 1); 23.3% of the participants were aged between 56-65 years (see Diagram 1). As regards their marital status, 44% of the sample was married, 39.3% are single, 10% are divorced, and 6.7% have another kind of arrangement in their personal lives.

C. The importance of the ethno-local factor: Sephardi(m) or Romaniote Jews?

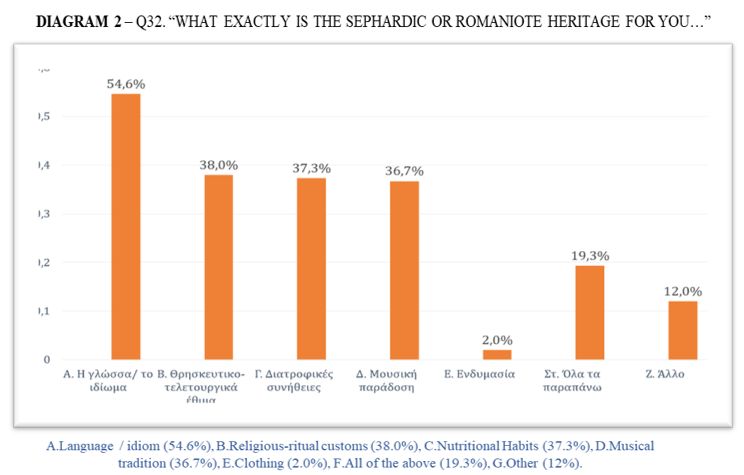

According to the research findings, most of the participants stated that they are of Sephardic origin (68.7%, see Table 1). Thus, the vast majority (84%) come from Jewish Sephardic parents. Undoubtedly, Sephardic culture is deeply rooted in the Thessaloniki, Trikala, and Larissa (Vernet Pons 2014: 297-313) communities. It is typical of the Salonika Jews that: “(to be) Thessalonian and not be a Sephardi, it is not possible,” as there is the description of Thessaloniki, the so-called “Jerusalem of the Mediterranean, the mother of Israel,” as Jerusalem was in the days of her glory. Characteristically, by the middle of the sixteenth century, Thessaloniki is said to have been the Jewish center of Europe, the Torah learning center of the Old Testament and the Talmud; Jews from all over Europe were coming there to live a spiritual life according to Jewish laws.5

Although today Sephardic tradition marks the dominant ethnic origin, it does not have the glamor and dynamism of the past, because, as Moren writes, there is “the agony of a culture” since it has already died twice, once with the Holocaust and once with its accession to secular Greek culture (Moren 2011). Of all the rich Sephardic heritage, the majority of individuals interviewed emphasized Judeo-Spanish gastronomy: “I am Sephardi because of the Spanish Jewish food.”6 (see also Eden and Stavroulakis 1997) Most participants traditionally retain this ethnic trait through family memories and narratives, as it is stated: “I am historically Sephardic, because of grandparents”7; “as a folklore element.”8 The importance of the ethnic factor among younger people either disappears completely or is indirectly inherent as a historical heritage from their parents. A young Jewish woman in Athens claimed: “It has prevailed, but not that it means anything, I have no knowledge, I happen to come from a Spanish-speaking family, we only have a strong memory.”9

On the other hand, the emblematic ancient Romaniote tradition of the Greek-speaking Jews (10.7%) has significantly weakened today in places that used to be full of Jewish life, such as Ioannina, Arta, Chalkida, and Trikala. More specifically, one participant comments that: “I cannot separate the Jew from the Sephardic and the Romaniote, every difference between us is now normalized.”10 The Chief Rabbi of Athens, Mr. Gabriel Negrin, informs us that: “Nowadays, there are no expressions ‘you will not take my child from them,’ or that ‘someone who does not speak Spanish is not a Jew.’ Some people embrace identity intensely, but there is no question of [no issue about--eds.] marrying one another.”11 Few experts on the Greco-Jewish idiom share their concerns, saying: “I know and speak with idioms in “Romaniotika,” we are counted on our fingers. Many times with Rabbi Negrin we exchange some phrases, honoring our grandparents, it is a reference to tradition from something that stimulates our memory.”12 A group of respondents has not maintained any ethnic traditions (18.0%), commenting: “I used to say that I was a Romaniote Jew, but in the course of my life I discovered that no ethnic difference matters. I feel that I am generally a Jew and more Greek.”13

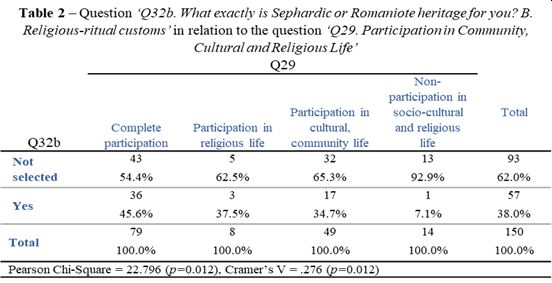

The importance of a particular ethno-local tradition to those who identify with it lies in language/idiom (54.6%, 51.3% Sephardic/Judeo-Spanish language), religious customs (38%), and food traditions (37.3%). Those who feel closer to the musical tradition (Kavvadia 2005) provide the following analysis: “It’s our music history. We learned it ourselves”14 (Eden and Stavroulakis 1997; Benrubi 2002) (see Diagram 2). The preference for Judeo-Spanish culture is supported by the characteristics of tradition or even habit: “It is a warm tradition, it has the Mediterranean temperament.”15 Another individual recalls: “The way we say the Sabbath prayer in Larissa is the Sephardic one, but you don’t sit down to think about it at that time, it’s embedded.”16

Sephardic customs have their place of honor, as they refer more to traditions than to rules. They are summarized mainly in Pesach hymns and gastronomic recipes and aromas which, especially in Thessaloniki, bring back family memories from the festive Jewish table (Kravva 2010; 2004a &b). For example, recipes such as leafy greens, onions, eggplants, such as “prasokeftedes,” “boumouelos,” “bogika,” “bigoules,” “yufka,” “bourekas,” “pasteliko,” “chaminados,” and “bourekitos.”17 Others emphasize a variety of popular music, many of which are love songs, such as “Adio Kerida” (Goodbye Beloved) and underline the sentiment that: “the Sephardim of the Ottoman Empire with their open temperament had the luxury of loving and singing!”18

On the other hand, some people interviewed wonder that it has been possible to create a fusion of Greek Byzantine and Jewish culture as a unique cultural treasure. Community members to this day (Fromm 2008; Nachman 2004; Connerty 2003; Dalven 1990) express surprise at this notion, as one interviewee states: “It is a very small part of Judaism which concerns us directly geographically and historically, that was created and lived in our Greek space.”19

An expected finding in the research is that the greater the participation of individuals in the life of the Jewish community, the higher the percentage of those who claim that religious heritage is an integral part of the Jewish heritage (see Table 2).

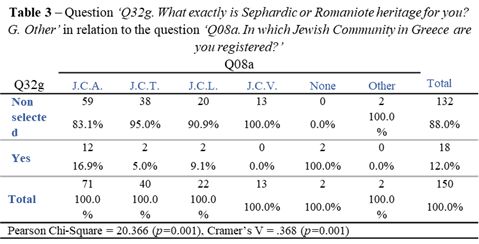

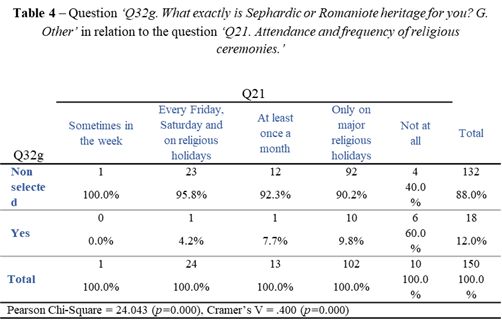

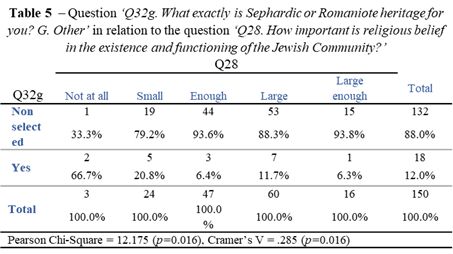

As for the Jewish community in which Greek Jews are registered, a different answer than the standard one was chosen by both participants who are not registered in any Jewish community, as well as 16.9% of the Athenians registered in the Jewish community (see Table 3). In addition, as attendance at religious ceremonies decreases, so does the percentage of the group that selects another answer (see Table 4). A similar relationship is presented with the question of the importance of faith for the existence of the Jewish community (see Table 5). In the alternatives (Other), respondents report that they are not only completely ignorant as generations go by, but also that they do not distinguish the ethnic element from the Jewish one because it has been incorporated. Furthermore, from conversations with young Jews, it seemed that many young people do not care at all for either the Sephardic or Romaniote heritage, or for the community activities and religious ceremonies. For some, it’s a matter of reputation since:

“Today the legacy they have left, the Sephardic and Romaniote tradition, is Judaism”20;

“At Pesach we can sing Romaniote songs, but it is not active, it is only a memory.”21

As already stated, it is understood that the influence of the ethno-local factor plays a minor role for the younger generations, as the customs and rituals practiced by the older generations tend to disappear. Young people do not experience any emotional attachment to Sephardic identity, as long as they note:

I do not know anything specific22;

I have never heard of them23;

My grandmother died without having been able to transfer any knowledge to me24;

I see it historically only as an origin. The Jews in modern life banish the old,

we have all become one thing, we have more or less the same religious

identity as traditional Jews.25

In contrast, those older participants who have retained knowledge of a few customs credit the family circle for transmitting them:

I learned growing up. There are things that you don’t remember how they went

through you26;

From our mother27;

My in-laws, because I didn’t meet grandparents because of the Holocaust28;

From my spiritual teacher in Larissa, Amore.29

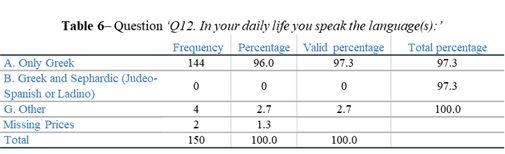

According to the findings, the majority of Greek Jews use only the Greek language (96.0%), but some have heard or use Judeo-Spanish or Ladino phrases in moments of intimacy: “When I want to say something to a loved one, for example to my son, ‘parariko’ (my little bird) or a ‘kerido’ (my beloved son).”30 Others say for emotional reasons: “I love Ladino as a native of Thessaloniki, but no more than Greek, we have a great emotional attachment to our homeland as Greek citizens”31 (see Table 6).

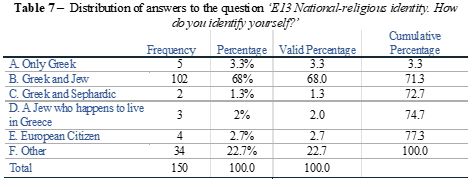

The current data suggest that the vast majority of participants (68%) define themselves as Greek and Jewish (see Table 7). Some of them identify with their Greek citizenship so strongly and emphatically that they claim:

We grew up here, we were born here! We are Greeks!32;

I served in the army, I strongly feel the Greek identity, it is my nationality.33

The observation in my research finds that the Greek-Jewish majority see the Jewish aspect of their identity as a traditional and historic heritage. Others appear purely secular, while religious practice has gained social significance. The Greek-Jewish diasporic identity contributes decisively to the creation of a cosmopolitan existence, because the Sephardic/Romaniote reference has weakened in relation to the past and has shifted in its role in the formation of personal and collective identity (Horowitz 2000; Elazar 1992).

D. Conclusions

The origin/ethno-local element of the Greek-Jews played a major role in the pre-war period. In contrast, my research shows that today it is not significant as an identifying element. The one-time cultural differences between the aforementioned two ethnic-local Jewish groups, which had a rich linguistic, religious, and functional diversity seems to be long outdated.

My research shows that the largest percentage of participants is of Sephardic origin and a few are Romaniote, therefore the existence of a homogeneous ethno-local Jewish identity is evident. The ethnic dimension with the reduction to the more recent Judeo-Spanish origin from the Iberian Peninsula, with the predominance of the no-longer-spoken traditional Sephardic language idiom (Judeo-Spanish or Ladino), or the older Romaniote, Greek-Byzantine origin, with the Romaniote(/ic) dialect (Judeo-Greek idiom), contributes in a dual way to the cultural and historical preservation of the Greek-Jewish identity. Today’s Greek Jews, with a predominantly Sephardic tradition, retain some particularly ethnic-local features, such as customs, religious traditions, and eating habits, either collectively (synagogue, spiritual center, Jewish school, camp), or within the family. In short, the elements of Sephardic culture form a dichotomy with the deeply rooted Greek-Jewish identity(-ies), in which the ethno-cultural dimension has almost absorbed the religious dimension in full harmony with local Greek social reality.

Bibliography

Alcalay, Artemis. 2018. “A Study On Trauma, Memory And Loss: Greek Jews Survivors of the Holocaust.” In The International Holocaust Remembrance Day 2018, Thessaloniki: Thessaloniki Concert Hall.

Altabé, David. 2000. “The Portuguese Jews of Salonica.” Pp. 119-124 in Studies on The History of Portuguese Jews, eds. Israel J. Katz and Mitchell M. Serels. New York: Sepher-Hermon Press.

Anastasopoulos, Nikolaos A. 2015. The Israelite Club of Ioannina During the Interwar Period: Establishment, Objectives, Presence (Η Ισραηλιτική Λέσχη Ιωαννίνων Κατά τον Μεσοπόλεμο: Ίδρυση, Στόχοι, Παρουσία). Ioannina: Foundation Gani Iossif and Esthir (in Greek).

Benrubi, Nina. 2002. A Sweet Life… And Bitter (Μια Ζωή Γλυκιά…Kαι Πικρή). Thessaloniki: Syghronoi Orizontes (in Greek).

Bickerman, Elias Joseph. 1988. The Jews in the Greek Age. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press.

Bowman, Steven. 2002. “Jews.” Pp. 64-80 in Minorities In Greece: Aspects Of A Plural Society, ed. Richard Clogg. London: C. Hurst.

Connerty, Mary C. 2003. Judeo-Greek: The Language, The Culture. New York: Jay Street Publishers.

Dalven, Rae. 1990. The Jews of Ioannina. Philadelphia: Cadmus Press.

Eden, Esin and Stavroulakis, Nicholas. 1997. Salonika: A Family Cookbook. Athens: Talos Press.

Elazar, Daniel J. 1992. “Can Sephardic Judaism Be Reconstructed?” Judaism 41(3): 217-228.

Fromm, Annette B. 2008. We Are Few: Folklore and Ethnic Identity of the Jewish Community of Ioannina, Greece. UK: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Hagouel, Paul I. 2013. “The History of the Jews of Salonika and the Holocaust: An Exposé.” Sephardic Horizons Vol. 3.

Hekimoglou, Evangelos. 2016. “The Religious Filter In The History Of The Urban Transformations; Sephardim In Thessaloniki.” Pp. 145-160 in Jewish Communities Between East and West, 15th-20th Century: Economy, Society, Politics, Culture (Εβραϊκές Κοινότητες Ανάμεσα Σε Ανατολή και Δύση, 15ος–20ός Αιώνας: Οικονομία, Κοινωνία, Πολιτική, Πολιτισμός), eds. Anna Macheira and Lida Papastefanaki. Ioannina: Isnafi.

Horowitz, Bethamie. 2000. Connections and Journeys: Assessing Critical Opportunities for Enhancing Jewish Identity (A report to the Commission on Jewish Identity and Renewal UJA-Federation of New York). New York: UJA-Federation of Jewish Philanthropies.

Kavvadia, Emmanouela. 2005. Aspects of Contemporary Jewish Music in Greece: Case of Judeo-Spanish Songs of Jewish Community of Thessaloniki. Ph.D. dissertation. London: Goldsmiths College.

Kravva, Vasiliki. 2004(a). “Food Αnd Identity: The Case Οf Τhe Jews Οf Thessaloniki” («Τροφή και Ταυτότητα: Η Περίπτωση των Εβραίων της Θεσσαλονίκης»). Ethnology (10) (in Greek).

Kravva, Vasiliki. 2004(b). “Our Foods Are Different From Your Own…” («Τα Δικά μας Φαγητά Διαφέρουν από τα Δικά σας…»). Ethnology 12 (in Greek).

Kravva, Vasiliki. 2010. “The Sephardic Jews Οf Thessaloniki: Nutrition Αnd Collective Memory” («Οι Σεφαραδίτες Εβραίοι της Θεσσαλονίκης: Διατροφή και Συλλογική Μνήμη»): 133-145 in Culture Αt Τhe Table, Thessaloniki: Archaeological Museum Οf Thessaloniki (Ο Πολιτισμός στο Τραπέζι, Θεσσαλονίκη: Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο Θεσσαλονίκης). Thessaloniki: Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki (in Greek).

Nachman Nachmias, Eftihia. (eds. Marcia Haddad Ikonomopoulos and Isaac Dostis). 2004. Yannina: A Journey To The Past. New York: Bloch Publishing Company.

Nar, Leon. 2018. I Νever Forgot Υou (Δε Σε Ξέχασα Ποτέ). Thessaloniki: Performing Arts Theater by KTHBE (in Greek).

Nehama, Joseph. 2000. The History Οf Τhe Jews Οf Thessaloniki (Η Ιστορία Των Ισραηλιτών Της Σαλονίκης) (Vols. A, B, C). Thessaloniki: University Studio Press (in Greek).

Sidiropoulou, Maria Ch. 2016. ‟Negotiating Female Identity in the Jewish Community of Thessaloniki: Between Tradition and Modernity.” European Society of Women in Theological Research 24 (1-11): 189-201.

Sidiropoulou, Maria Ch. 2018a. “The Holocaust and the Reclamation of Memory: The Case of the Jewish Community in Thessaloniki.” Holocaust. Study and Research 11(10): 207-242.

Sidiropoulou, Maria Ch. 2018b. Alef (Άλεφ) 71: 10-12 (in Greek).

Sidiropoulou, Maria Ch. 2019. “The Position of Greek Jewish Women Ιn Public Space: Ethical And Social Dimensions” («Η Θέση Των Ελληνίδων Εβραίων Στο Δημόσιο Χώρο: Ηθικές Και Κοινωνικές Διαστάσεις»). Synthesis E-Journal 6(2): 77-100 (in Greek).

Sidiropoulou, Maria Ch. 2020a. Greek Jews in Contemporary Greece: Swirling Paths To Modernity (Οι Έλληνες Εβραίοι Στη Σύγχρονη Ελλάδα: Η Περιδίνηση Στη Νεωτερικότητα). Thessaloniki: University of Macedonia Press (in Greek).

Sidiropoulou, Maria Ch. 2020b. “Modern Greek Jewish Women: Paths and Identities”. Women in Judaism: A Multidisciplinary E-Journal 15(2).

Varon Vassard, Odette. 2018. Presentation in Sephardic Jews - History, Culture (Σεφαραδίτες Εβραίοι - Ιστορία, Πολιτισμός). Athens: Ministry of Digital Policy, Telecommunications and Media (in Greek).

Varon Vassard, Odette. 2019. “The Emergence of a Difficult Memory” («Η Ανάδυση Μιας Δύσκολης Μνήμης»). Presentation in TEDx University of Crete. Crete: TEDx (in Greek).

Vernet Pons, Mariona. 2014. “The Origin of the Name Sepharad: A New Interpretation.” Journal of Semitic Studies LIX(1): 297-313.

1 Dr. Maria Ch. Sidiropoulou is a Postdoctoral Researcher in the Department of Ethics and Sociology, and a Research Associate and Founding Member of the “Social Research Centre for Religion and Culture” (ΕΚΕΘΡΗΠΟ) in A.U.Th. (Greece). Her scientific research is focused on the Holocaust, anti-Semitism, and the empirical study of modern Greek Jewish identity(-ies) and its contemporary identitarian aspects from a sociological perspective. Her postdoctoral research is on the effect of the Holocaust on the Greek-Jewish self-consciousness; it answers the question: “Is religion ‘replaced’ by the Holocaust, or not?” Her first book is Greek Jews in Contemporary Greece: Swirling Paths to Modernity (Οι Έλληνες Εβραίοι Στη Σύγχρονη Ελλάδα: Η Περιδίνηση Στη Νεωτερικότητα). Thessaloniki: University of Macedonia Press. 2020 (in Greek).

2 J.C.T. Jewish Community of Thessaloniki, J.C.L. Jewish Community of Larissa, J.C.V. Jewish Community of Volos.

3 The qualitative and quantitative data that are presented herein are part of my dissertation findings as submitted in 2018 in the Department of Ethics and Sociology, School of Theology, Faculty of Theology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. It was published as Greek Jews in Contemporary Greece: Swirling Paths to Modernity (Οι Έλληνες Εβραίοι Στη Σύγχρονη Ελλάδα: Η Περιδίνηση Στη Νεωτερικότητα). Thessaloniki: University of Macedonia Press. 2020 (in Greek).

4 In Greece, today, there is an active Jewish female presence. In Athens, there is a branch of WIZO (Women’s International Zionist Organization, 1935). In some areas of the capital, other Jewish women’s groups such as AVIV (1963) (e.g. AVIV in Glyfada, in Kifissia) are active. Jewish women’s organizations also support the Lauder Athens Jewish Community School; they host cultural and educational events and have published a Jewish cookbook. In Thessaloniki, one Jewish women’s charitable association, Ziv (light, glow), is tasked with the preservation and conservation of the Jewish cultural heritage including support of the poor. The women themselves point out: “... (Help goes to) those who have substantial need in the city.” From interviews with Jewish Women (56-65) in Thessaloniki, Greece (September, 2016) (See, Sidiropoulou 2016).

5 Interview with a Jewish Man (66-75) in Thessaloniki, Greece (February, 2017).

6 Interview with a Jewish Man (75+) in Thessaloniki, Greece (November, 2016).

7 Interview with a Young Jewish Woman (18-25) in Athens, Greece (January, 2017).

8 Interview with a Young Jewish Woman (26-35) in Thessaloniki, Greece (March, 2017).

9 Interview with a Young Jewish Woman (26-35) in Athens, Greece (December, 2016).

10 Interview with a Jewish Woman (56-65) in Volos, Greece (April, 2017).

11 Interview with the Chief Rabbi of the Jewish Community of Athens (J.C.A.), Mr. Gabriel Negrin, cantor, mohel, shochet (Beth Shalom Synagogue, Athens, September 30, 2016).

12 Interview with a Jewish Man (56-65) in Athens, Greece (December, 2016).

13 Interview with a Jewish Man (36-45) in Athens, Greece (January, 2017).

14 Interview with a Young Jewish Man (18-25) in Thessaloniki, Greece (September, 2016).

15 Interview with a Jewish Woman (56-65) in Thessaloniki, Greece (October, 2016).

16 Interview with a Jewish Man (56-65) in Larissa, Greece (May, 2017).

17 In English, “Prasokeftedes”: leek balls; “Boumouelos”: donuts from unleavened flatbread [matza(-h)]; “Bogika”: Romaniote sweet; “Bigoules”: homemade pasta; “Yufka”: wrapped appetizers and snacks; “Bourekas”: pie made with phyllo, with potato, mushroom, eggplant, spinach, cheese; “Pasteliko”: pie with eggplant and minced meat; “Chaminados”: Braised eggs, whole eggs in the shell, which are placed on top of a “hamin” (a Shabbat stew on Saturday); “Bourekitos”: puff pastry filled with either cheese or a mixture of feta (white cheese), mashed potato, mushrooms, spinach and eggplant.

18 Interview with a Sephardic Jewish Man (75+) originally from Thessaloniki, now lives in Athens, Greece since the post-war period (December, 2016).

19 Interview with a Sephardic Jewish Man (75+) who lives in Athens from the post-war period, but he comes from Thessaloniki, Greece (December, 2016).

20 Interview with a Young Jewish Man (18-25) in Larissa, Greece (May, 2017).

21 Interview with a Young Jewish Man (18-25) in Athens, Greece (September, 2016).

22 Interview with a Young Jewish Woman (26-35) in Athens, Greece (January, 2017).

23 Interview with a Young Jewish Woman (18-25) in Athens, Greece (December, 2016).

24 Interview with a Young Jewish Woman (18-25) in Athens, Greece (December, 2016).

25 Interview with a Young Jewish Man (46-55) in Athens, Greece (September, 2016).

26 Interview with a Jewish Woman (56-65) in Larissa, Greece (May, 2017).

27 Interview with a Jewish Woman (75+) in Larissa, Greece (May, 2017).

28 Interview with a Jewish Woman (36-45) in Athens, Greece (December, 2016).

29 Interview with a Jewish Man (56-65) in Larissa, Greece (May, 2017).

30 Interview with a Jewish Woman (56-65) in Thessaloniki, Greece (October, 2016).

31 Interview with a Jewish Woman (56-65) in Thessaloniki, Greece (September, 2016).

32 Interview with a Jewish Man (66-75) in Thessaloniki, Greece (April, 2017).

33 Interview with a Jewish Man (66-75) in Athens, Greece (November, 2016).

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800