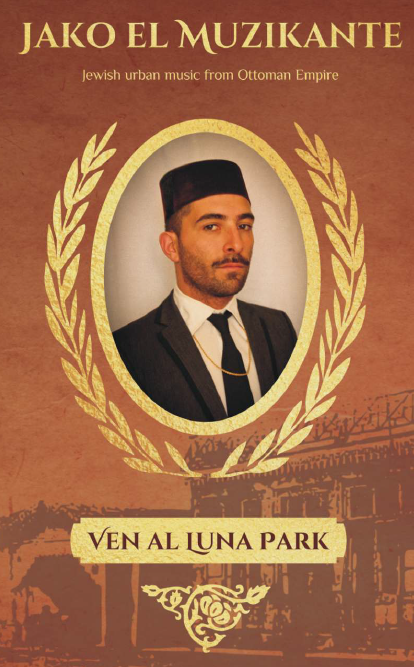

Jako el Muzikante

VEN AL LUNA PARK

Mapamundimusica, CD and Book, 2019

Reviewed by Leonard Stein1

In his 1946 memoir, Farewell to Salonica, the Sephardi writer Leon Sciaky (1893-1958) depicted the cosmopolitan, multi-lingual culture of his childhood city before it irrevocably shifted into the impending nationalist violence of the Young Turks Revolution and the First World War. Far away in New York, a land he fled to in 1915, Sciaky would reminisce of another city life, the kind textured with the noisy taverns near his home:

Early in the evenings the patrons would burst into songs, harmonizing and blending their voices into beautiful choruses. As the hours wore on, however, the tempo would change. Stamping feet and clinking glasses would beat the time restlessly and the voices would become hoarser and the singers befuddled.

Ta horepsome ki ta piume, ki ta pandrepsome. (Greek)

We will dance and we will drink, and we will get married.

As often as not the laughter and mirth would end with the broken bottles and loud curses of a drunken brawl.2

Sciaky here depicts a gathering of Greek singing, but neighboring Salonican Jews similarly performed and listened to live music in their own vernacular Judeo-Spanish, commonly referred to as Ladino. Weddings, circumcisions, and other Jewish occasions demanded festive music, as did public spaces like coffee shops. Despite a vast storehouse of transmitted songs compiled through the oral fieldwork of musicologists, we have limited access to how this music sounded at the turn of the century. Starting in 1907 with the Izmir cantor Salomon Algazi and most successfully developed by the Edirne singer Haim Effendi, record companies like Gramophone and Odeon opened the door for a limited number of Ottoman Jewish musicians to produce Ladino albums before the First World War, after which Ladino music was recorded in other locales (mostly New York).

The Galician singer, percussionist, and scholar Xurxo Fernandes, under the persona Jako el Muzikante, has produced an exceptional album of Ladino music that imagines those chaotic, vibrant, and actually fun sounds from the end of the Ottoman Empire. Although still an under-represented genre in the world of Jewish music, Ladino performers today often lean on familiar and expected styles of singing; a popular repertoire of songs usually sounding nostalgic, operatic, or erotic. The chief accomplishment of Ven Al Luna Park is Fernandes’s innovative approach to perform Ottoman Ladino urban music, which sounds not like a reminiscence of things past, but something very much alive. The excellent production of these thirteen recordings offers a crisp sound to the acoustic instruments (e.g., violins, tambourines, oud, and double bass) and backup vocals, all accompanying the nimble voice of Fernandes. These are not lullabies or Sabbath table hymns, but songs that evoke a loose, outdoor atmosphere filled with smoke, coffee, and probably even stronger stuff.

The album covers an eclectic range of secular topics in songs mostly unfamiliar to Ladino music listeners. The first track, and the namesake for Fernandes’s persona, “Jako el muzikante,” centers on an artful singer who steals items from the bags of audiences, while in “Si no me dan tus paryentes, [If your relatives don’t gimme gimme],” Fernandes sings in the biting voice of a bride threatening the groom and his whole family with elaborate consequences if her dowry is not sufficiently met. Actually, a number of songs are humorous, and even someone who doesn’t understand Ladino will laugh at the animal noises of the satiric “Madam Gaspard.” The most familiar track on the album, and my personal favorite, the romance “Noches Noches,” leaves the festive, coffee shop atmosphere for a nightly, meditative space. Accompanied by a haunting clarinet, Xurxo’s gorgeous melismatic voice, singing “noches, noches, buenas noches, noches son de namorar [Nights, nights, good nights, nights are for falling in love]” could be mistaken for a Sufi mystical prayer. Perhaps the rendition is influenced by “Melisenda Insomne, [Sleepless Melisenda],” the Ladino song it derives from and, as the liner notes explain, that song’s inclusion into the crypto-Jewish Sabbatean liturgy in the seventeenth century.

The book that comes with the CD merits its own purchase. Fernandes provides detailed notes for each song, which include pictures of early twentieth century Sephardic performers, variations of recorded renditions, historical and contextual information showing the artist’s impressive research, and lyrics. The book replicates this into three languages: Ladino in Latin script; English; and, curiously, Ladino in Rashi Hebrew script. Although the album does not elaborate on this choice, I understood the Rashi Ladino as an attempt to reproduce the image of the songs as much as the sound of the recordings. Most listeners will likely follow Ladino lyrics more easily in Latin script, but the added section reminds listeners that Ottoman Ladino speakers at the turn of the century would have printed their poetry and newspapers differently. Unfortunately, the English section of the album contains an excessive amount of grammatical and spelling errors, likely the result of a non-native translator.

The album and book showcase Fernandes’s many talents as singer, percussionist, field worker, Ladino editor, and translator. The eleventh track, “Maldicha Kokaina [Cursed Cocaine]” derives from the Greek song, “Giati Foumaro Kokaini [Why Do I Smoke Cocaine],” performed by the celebrated Sephardi Greek singer and cabaret performer, Roza Eskenazi. Fernandes details the fascinating story of Eskenazi, one of the most important figures in the history of the Greek folk music known as rebetiko, who managed a successful and independent career for some five decades until her death in the 1970s. Despite her upbringing in a Ladino-speaking household, Eskenazi performed and recorded as a Greek singer. Fernandes thus pays homage to her Sephardic identity by translating “Giati Foumaro Kokaini,” which Eskenazi recorded in 1932, into her mother-tongue of Ladino. The homage is complemented by the multimedia experience of the album. Few musicians today create new Ladino lyrics, and the translation highlights Eskenazi’s career while expanding the vision of what Ladino urban music comprises. The track, starting from the opening violin riff, to Fernandes’s pained singing of having to resort to cocaine after heartbreak, to the singer’s spoken asides, ably honors Eskenazi’s style of singing. Those unfamiliar with the queen of rebetiko can then learn about her by reading Fernandes’s treatment.

This album is highly recommended for anyone interested in Ladino music and Sephardic culture. Like so many early recordings, the authentic Ladino songs that I love to hear always come with the pops, scratches, and hisses of worn-out records, but the clean sound of Jako el Muzikante’s Ven Al Luna Park offers something even better: a faithful and lively album that manages to both transport the past into the immediate present while simultaneously develop the future of Ladino performance.

1 Leonard Stein is a Ph.D. Candidate for the Centre for Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto, a Broome & Allen Fellow at the American Sephardi Federation, and the editor for University of Toronto Journal of Jewish Thought. His research compares modern literature from the Sephardic diaspora, specifically representations of al-Andalus and the Spanish Inquisition.

2 Leon Sciaky, Farewell to Salonica: City at the Crossroads (1946; repr., London: Haus Publishing, 2007), 93.