The Caribbean Sephardim in the Ḥaluqah System: From Jerusalem to the

West Indies and Back

by Yehonatan Elazar-DeMota1

Abstract

Before the rise of Zionism, Jews living in the Land of Israel were supported by the ḥaluqah system. Sephardim played an important role in the collecting and distribution of funds throughout the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries. Yet, little is known about the involvement of the Caribbean Sephardim in the ḥaluqah. This paper explores those communities, the Ḥakhamim, and the travel patterns undertaken in order to maintain a Jewish presence in the Land of Israel.

A belief exists among Jews that if prayer from Jerusalem ceases for a moment, the world will return to its primeval chaos. In order to ensure that this never happens, no matter how small the population, Jews must be ever-present in the Holy City. Before the fifteenth century, the Jewish population in the Land of Israel was minuscule, nevertheless, significant. After the Expulsion of the Sephardim from Spain and the forced conversions in Portugal, the Jewish presence in Ereṣ Israel (the Land of Israel) increased considerably. Almost simultaneously, the Sephardi diaspora communities developed into economic centers, whether in Europe or in the Americas.

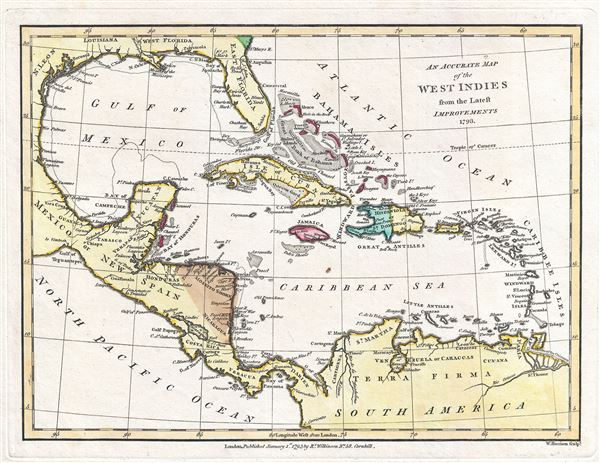

The now-neglected Caribbean Sephardi communities were at the forefront of trading and wealth in the eighteenth century. Through their money and influence, the Caribbean Sephardim managed to send continual financial support to the Jews living in the four holy cities. The capital of the Ottoman Empire served as the center of a “far-flung philanthropic network in support of the Jews” in Ereṣ Israel, “linking Jewish communities throughout the empire and beyond, from the Caribbean in the west to India in the east, and from England in the north to Yemen in the south” (Lehmann 1). Rabbinic emissaries were sent throughout the Jewish world, collecting pledges and contributions, which were then sent to Constantinople and distributed to Jerusalem, Safed, Ḥebron, and Tiberias (Lehmann 2)

The ḥaluqah was an organized system of collection and distribution of charity funds for Jewish residents in the Land of Israel. Jews from all over the world would donate charity to this cause. The ḥaluqah divided its funds in three equal parts. One part was given to Torah scholars. Another third was given to widows and orphans, and the last third was to pay taxes. This paper will detail the historical accounts of the emissaries, their missions, their plights, and their successes and give a historical account of the Nação in Amsterdam, her daughter communities in the Western hemisphere, and their interactions with Sephardi communities in the Land of Israel. The primary focus will entail a survey of the Caribbean Sephardi communities that played a significant role in the ḥaluqah system.

THE NAÇÃO IN THE NETHERLANDS

In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, some Portuguese anusim established themselves in the Netherlands. Their first community was founded in 1602 in Amsterdam, with the help of an Ashkenazi rabbi from Emdem. Later in 1608, David Pardo, a Venetian rabbinic scholar also settled there. He was appointed Ḥakham of Beth Jacob. A year later, the Moroccan-born ambassador, Samuel Palache, started a congregation called Neweh Shalom. The time of the establishment of these communities was opportune. As a result of the trade treaty between the Dutch and the Portuguese, many opportunities were forged for the Jews of the Portuguese Nation, henceforth, the Nação. Thus, the elite of this newly founded community were brokers and merchants. They formed part of the Ma’amad (the Board of Trustees), which was often labeled as an oppressive autocratic regime. The Ma’amad consisted of seven parnasim (chief administrators) who ultimately were responsible for the identity and vision of the community. In 1639, the communal leaders united under one roof to form Kahal Kadosh Talmud Torah. By that time, the community had “demographic strength, wealth, and rabbinic stature” to trek forward (Bodian 51).

THE CARIBBEAN SEPHARDIM

One of the first trade settlements established by the Nação in the Western Hemisphere was in northeastern Brazil. Brazil was claimed by the Portuguese navigator Pedro do Noronha. Soon after, many Portuguese anusim2 were banished there. In 1630, the Dutch invaded and took possession of the entire territory by 1635. During that time, a Jewish congregation was founded in Recife called Ṣur Israel. The former anusim were able to practice their ancestral faith openly. Talmud Torah of Amsterdam sent Ḥakham3 Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, the first rabbinic scholar to the Americas, as the spiritual guide of this outpost.

Unfortunately, the Portuguese took over the Dutch administration in northwestern Brazil in 1654; many Jews returned to Amsterdam. Another group dispersed throughout the Caribbean, including, but not limited to Jamaica, Curaçao, and Barbados (Gerber 4). Soon thereafter, Curaçao became the hub for Caribbean Sephardim and the center where Iberian anusim could revert to the Jewish tradition (ibid 68).

By the end of the eighteenth century, the Dutch trading system had provided the Portuguese Jews a golden opportunity to gain prominence and wealth, not only in the ‘New World’, but also as far as India (ibid 30). Their knowledge of the Romance languages and sense of peoplehood gave them the upper hand in the Caribbean trading market of cash crops - sugar, indigo, tobacco, and more. Some of the anusim who reverted to Jewish tradition in Protestant European territories, used their liminal identities to take advantage of commerce throughout the Americas and the Mediterranean.

Yerushalmi asserts, “Outwardly Christian, they could penetrate into areas from which professing Jews were excluded. Already in the sixteenth century we find them in Southwestern France, in London, in Spanish Flanders, and throughout the far-flung Spanish and Portuguese overseas empires” (Yerushalmi 177). They established communities in congruence with the trading posts throughout the British and Dutch West Indies. All of these Jewish communities were linked with a gente da Nação in London, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Livorno, Constantinople, and ultimately, Jerusalem.

The communal records of charities and distribution of funds demonstrate that the Nação in Recife used to make regular contributions to the Holy Land via Amsterdam (Emmanuel 1970, 484). On Shabbath Naḥamu (the Sabbath after the Ninth of Ab), Recife congregants made pledges for donations on behalf of the poor of the Holy Land (Wiznitzer 243).

Jamaica

The first Jewish settlement in Jamaica was established in 1530, by Spanish and Portuguese anusim who fled the Inquisition. Mordechay Arbell asserts, “Various cases show that the Jews continued to arrive from Spain and Portugal directly to Jamaica, sometimes passing through France” (Arbell 2000, 8). Those Jews made every effort not to be identified as such because the Inquisition was in full force. On May 21, 1577, a repeal of the edict prohibiting the emigration of the anusim went into force. Delevante states, “From then on, with the payment of 1,700,000 cruzados, conversos and Jews in the colonies were allowed freedom of residence and trade, if not religious practice” (Delevante 9). After Jews were expelled from Brazil in 1653, many of them resettled in Jamaica. Don Pedro Nuño Colon de Portugal, a descendant of Columbus, inherited the island from Columbus’ granddaughter in 1636. After the Jews met with him, he agreed to allow them to settle there (Arbell 2002, 7).

With the English conquest of the island in 1655, the anusim could practice the Jewish tradition openly. Spanish Town, originally St. Iago de la Vega, saw the first official Spanish-Portuguese Jewish community of Jamaica. This period coincided with the meeting between Ḥakham Menashe Ben Israel and Oliver Cromwell in London. In 1655, Jews were allowed to return to England officially for the first time since the expulsion in the thirteenth century. Arbell states, “This led to the new settlement of a number of Amsterdam Jews in Jamaica. They were joined by Jews from Bordeaux and Bayonne, transit points for Jews leaving Portugal and seeking safe places to live. These Jews settled in Port Royal for the most part” (Arbell, 2000, 11). In 1692, a Spanish-Portuguese congregation was founded there. The synagogue, Neweh Shalom, which served as the center for Jamaican Jewry was built in 1704.

Barbados

The first Jews arrived in Barbados in 1628. After the Dutch ceded Recife to the Portuguese in 1654, many of the Jews evacuated from Brazil in 1667 and went directly to Barbados. By 1656, after having received protection, emissaries were sent to the mother community in Amsterdam to bring back Torah scrolls and other religious paraphenalia. Their main settlements were in Bridgetown and Speightstown. Others went via Suriname or Guyana in 1674. Yet others came to the island from England.

The early pioneers cultivated sugar plantations. This community flourished throughout the eighteenth century and received full rights in 1802. After the destruction of coffee plantations in 1831, many Jews left for England and the United States. Despite having gained full rights on Barbados, the Jews were not always at peace with their non-Jewish brethren. Darnell Davis notes the following in 1846:

Whereas upon the humble Petition of Antonio Rodrigo Rigio, Abraham Levi Regio, Lewis Dias, Isaac Jeriao Coutinho, Abraham Pereira, David Baruch Louzado, and other Hebrews, made free Denizens by His Majesty’s Letters Patents, and residing at Barbados…divers persons of said Island do endeavour to deprive them of the benefit thereof, and refuse to admit their testimony in Courts of Judicatures, and expose them to all sorts of injuries in their Trade… (Davis 131).

By 1928, the original synagogue Nidḥe Israel in Speightstown was no longer in use. The community continued to dwindle well into the twentieth century.

Curaçao

Jewish settlement on Curaçao began in 1651, when João Yllan was given a permit to settle on the island, along with other Jews. A year later, Joseph Nunes de Fosenca was also issued a permit to settle there. The wealthy Jews were brokers, large-scale merchants, and international traders, whereas the lower class consisted of small tradesmen. Thus, there were two communities: one in Willemstad for the rich and another in Otrabanda for the lower class. Miqweh Israel was the synagogue built in Willemstad. The original by-laws were drafted in 1688. The parnasim permitted a second synagogue in Otrabanda called Neweh Shalom in 1732. By 1746, the Sephardi population on the island had reached its demographic peak of circa 2,000 people (Gerber 87) and the membership of Neweh Shalom had a visible presence in the Jewish community (ibid 88).

The Ma’amad, as introduced above, was given authority in all matters of Jewish life in the Portuguese community of Amsterdam. This had implications on Curaçao and often led to conflicts. The Curazoan Jews generally preferred Ḥakhamim4 from Turkey or Greece, since they were more sympathetic of their laissé-faire lifestyle. Sometimes, members were excommunicated from the community because they disobeyed or disrespected the orders of the distant Ma’amad in Amsterdam. Such was the case of David Aboab, an Italian Jew who was knowledgeable in Jewish law. He clashed severely with Ḥakham Raphael Jesurun and with Ḥakham Samuel Mendes de Sola over the duty of the deceased’s sons to provide for a tombstone (Emmanuel 1957, 120). Moreover, by 1864, a group of reformed Jews wanted to include the pipe organ in their services. The result was an offshoot community called Temple Emmanuel. Ironically, in 1964 Miqweh Israel and Temple Emmanuel merged to form Miqweh Israel-Emmanuel. Today, this community identifies itself as egalitarian and reconstructionist.

Dominican Republic

The first Jews arrived in the Americas during Columbus’ three trips to Hispaniola. Carlos Deive offers a detailed description of the presence of anusim in Hispaniola. He states that during Columbus’ first trip to the West Indies, the crew was composed of ninety men, of which many were, indeed, anusim. He states further that at that moment, there was no legislation prohibiting anusim from being part of the crew (Deive 57). According to Deive with regards to Columbus’ second trip, “about a dozen, or perhaps more anusim participated in Columbus’ second trip…the New Christians were Juan de Ocampo or del Campo, Antonio de Castro, Efraín Bienvenido de Calahorra, Álvaro de Ledesma, Iñigo de Rivas, and García de Herrera” (ibid 60). He affirms that criminals and incarcerated evildoers were forgiven upon joining Columbus’ crew on his third trip.

The first explicit mention that denies entry of the harassed anusim by the Inquisition to the Indies, however, is found in the provision of June 22, 1497 (ibid 65). Later, in May 1509, the same prohibition was repeated in the instruction to Diego Colón. In fact, at least five anusim from Seville arrived in Hispaniola aboard the Santa Maria Magdalena ship with him in 1502 (ibid 98). Deive states that many anusim paid their way into the Indies; they changed their names and reordered their surnames to depart from Spain (ibid 68). By the time Fray Bartholomé de las Casas arrived in Hispaniola, a large and powerful enough nucleus of anusim was there in order to compete with the “Old Christians” for the encomiendas (land grants) (ibid 72). For this matter and since the anusim were reluctant to follow Christian principles, Fray de las Casas suggested the inauguration of the Inquisition on Hispaniola (Bissainte 81).

The presence of Portuguese Jewish merchants was prevalent on Hispaniola, especially during the seventeenth century. In August, 1596, a witness of the Hearing of Santo Domingo wrote to the King that:

…after having examined certain passports, that José Rodríguez, Portuguese, declared that he had neighbors in the aforementioned city (Santo Domingo) that were leaving for England to the house of Duarte de Rivero, apparently affirming also that Simón Herrera, Ramón Cardoso, and Juan Riveros, Portuguese men, [were] leaving for England with their titles to plantations, and declaring that they were Jews, and that they were departing in order to practice the Law (of Moses) in liberty; two were arrested and the other sent to Puerto Rico, implying that there were many Jews living according to their Law, not only in Santo Domingo, but in other parts of the West Indies… (Ayala 56)

Indeed, many Iberian anusim came in and out of Hispaniola as secret Jews. As long as the Inquisition held tribunals in New Spain and Cartagena de las Indias, Jews were not able to practice openly and freely in Spanish territories. Kritzler asserts that “in the Treaty of Madrid in 1670, Spain acceded to Europe’s right to settle the ‘New World’… and Jews were finally free to be Jews” (10).

Spanish and Portuguese Jews from Jamaica, Curaçao, Amsterdam, and St. Thomas began arriving in Hispaniola in the early eighteenth century. They engaged in the sugar, tobacco, and coffee industries. Some prominent families within their network helped the Dominican Republic gain independence by supplying funds for artillery and ammunition. After gaining independence from Haiti in 1844, many Jews came from Curaçao. They established a community called Congregación Israelita, led by the cantor Raphael Namias Curiel by the end of the nineteenth century.

SEPHARDIM IN THE HOLY LAND

After the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 and the forced conversion in Portugal in 1497, the Ottoman Empire opened its borders to Sephardi refugees. The Ottoman ruler Bayazid II (1481-1512) saw the expulsion of the Spanish Jews as an opportunity. Thus, he gave the exiles refuge and hope (Zohar 152). Some passed through Cairo and Salonika, to eventually settle in the Land of Israel. Upon arriving there, they established themselves in Jerusalem, Safed, Tiberias, and Ḥebron. Their presence helped reinforce the extant Jewish communities there, while they founded new settlements. The eminent Sephardi centers became Constantinople, Salonika, Fez, Naples, Ferrara, and Cairo (David 64).

Jerusalem

Before the fifteenth century few Jews lived in Jerusalem. Only after the Sephardi exiles went to the Holy Land, did Jerusalem become a center of Jewish scholarship. According to Abraham David, “Starting from 1510, additional information is available on the presence of Spanish exiles in Jerusalem, alongside their counterparts from the other kehalim”5 (David 65). He also affirms, “From the 1520s to the mid-to-late 1570s, however, the Sephardim rose to dominance with the communal structure [Jerusalem], even absorbing some of the other kehalim” (David 65). There were so many Sephardim in Jerusalem that the Arabic-speaking Jews adopted the Sephardi culture and languages. Furthermore, Levi Avigdor asserts that the influx of Iberian scholars and Kabbalists to Jerusalem revitalized Jerusalem as the center of Jewish scholarship (Levy 39). Sixteenth century Jerusalem witnessed prominent scholars such as Levi ibn Ḥabib (ca. 1483-1545), David ibn Abi Zimra (ca. 1479-1573), Beṣṣal’el Ashkenazi (ca. 1520-1591), and Ḥayyim Vital (ca. 1479-1573) (ibid). Thus, the tragedy of the expulsion from Sepharad brought a blessing in disguise for Jerusalem’s Jewish communities.

Ḥebron

Ḥebron is one of the four holy cities of the Land of Israel. The Hebrew patriarchs are buried at the cave of Maḥpelah there. According to Abraham David, Ḥebron’s Jewish population in the 1480s comprised about twenty families (David 24). After the Expulsion from Sepharad, a few families went to Ḥebron by way of Salonika. Another source states, “Ḥebron’s sixteenth-century Jewish population fluctuated between eight and twenty families” (ibid). Most important, there was a prominent yeshibah6 called Talmud Torah. Ḥebron birthed many outstanding rabbinic scholars throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries including Isaac Ḥayyim Carigal, Ḥayyim Yosef David Azoulay, David Melamed, Meir Gedalia, Mordekhay Zoabi, Ḥayyim Yehudah Gomez Patto, Ḥayyim Raḥamim Bagiaio, and Isaac Ṣedaqah, to name a few (Yaari 580). In 1929, because of rumors that they were planning to take hold of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, the Ḥebron Jewish community suffered a massacre. Many of the four hundred and thirty-five Jews who survived were saved by local Arab families. Overall, the Jewish community in Ḥebron has remained small in number, yet important in Jewish scholarship and leadership.

Safed

Another important holy city in the Land of Israel is Safed. It became the bedrock of the Kabbalistic tradition there and had eighteen yeshiboth and twenty-one synagogues. The oldest synagogues in Safed reveal the strong presence of the Sephardim through their architecture and interior design. Various sources mention that the origin of aliyah7 to Safed was Ottoman Salonika. In 1523, David ha-Reubeni, a messianic pretender, was responsible for instigating a mass movement of Sephardim from Salonika to Safed (David 16). The vast majority of them were former anusim from Portugal (ibid 17). David also asserts that the Iberian exiles had a preference for Safed, as early as 1504 (ibid 65). Furthermore, he states:

With the marked increase in immigration following the Ottoman conquest, our knowledge of the various kehalim in Safed, including the Sefardi one, is enhanced. Only a few short years after the inception of Ottoman rule, the Sefardi kahal, composed of expellees from the Iberian Peninsula who reached Eretz-Israel from various points in the Sefardi diaspora—Turkey, the Balkans, North Africa, Egypt, and Syria—dominated Safed (David 102).

Because of teachings in the Zohar that the Messiah would first appear in Galilee (ibid 104) immigration to Safed gained importance. All in all, Safed was primarily developed by Portuguese and Spanish former-anusim exiles who thought the Messianic Era to be at hand after the Expulsion in 1492.

THE ḤALUQAH SYSTEM AMONG SEPHARDI COMMUNITIES IN THE LAND OF ISRAEL

Matthias Lehmann states that, “Jewish financial support to the Holy Land before the seventeenth century was haphazard” (Lehmann 18). Before Constantinople became the center of movement between Asia, Europe, and the Americas, financial contributions were sent to Venice (Lehmann 20). Special voluntary associations in charge of collecting money for pidyon shebuyim8 were established in the Western Sephardi communities in Amsterdam, London, and Hamburg. Funds were collected by the gibber kelali.9 Different funds were solicited for the ransoming of captives held by the Inquisition or by pirates, especially among the Portuguese Jews. They also had a “dowry” society for poor brides.

The Nação in Amsterdam established funds for Terra Santa (Holy Land) in the early seventeenth century. The activities of this charity were recorded in registers of the respective communities. The Terra Santa fund is first mentioned in the financial registers of Beth Jacob and Neweh Shalom (GAA 334, 19, 20, 21).

When the Ottoman Empire expanded to the region of the Land of Israel, it began charging the Jews taxes, due to their dhimmi10 status. In the latter part of the sixteenth century, when there was a revenue crisis, taxes for the Jews increased and the task of taking care of the poor became heavier. “As a result of all these changes, more centralized community structures began to make their tentative appearance” (Levy 65). For the purposes of taxation, the function of Ḥakham Bashi11 was instituted, as it had also been used in medieval Islamic Spain (ibid 45). A lot of money was given to the poll tax for non-Muslim citizens, and to bribe Ottoman officials in the Land of Israel. This created a deficit that haunted the Jewish communities. Sometimes throughout the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries the qadi (Islamic judge) in Jerusalem asked for more money, creating an increasing problem.

According to Raphael Mordecai Malki, the Jews of Jerusalem were paying about 5,000 kuruş a year in taxes, even though Ottoman documents suggest that only about 2,000 kuruş of djizya were collected in the early 1700s. Malki also provided an estimate of the financial needs of the Jerusalem community, indicating, on the one hand, that the bulk of the budget was needed to keep up with the poll tax and other payments to the Ottoman provincial authorities and, on the other hand, that only the ongoing support from the Jewish Diaspora could sustain the Jerusalem community financially (Lehmann 24). This is the context that led Sephardi scholars from the Land of Israel to explore fundraising in the tropics of the Caribbean.

THE MESHULAḤIM

Almsgiving and charity are at the core of the Jewish tradition. The Torah states, “Poor persons will never disappear from the earth. That’s why I’m giving you this command: you must open your hand generously to your fellow Israelites, to the needy among you, and to the poor who live with you in your land” (Deuteronomy 15:11, my trans.). Furthermore, the Talmud states, “that the giving of ṣedaqah is equal to all the other commandments combined” (b.Bath.9b). In order to ensure that this precept is guarded, it has been customary over the centuries to have a box for charity in every home. Jews place ṣedaqah boxes in all rooms of the house, except the restroom. Many business owners have charity boxes at their restaurants and places of business. At the synagogue, it is still customary for men to place money in the charity box on a daily basis, except for the Sabbath when money is not handled. These funds are distributed to the yeshiboth, orphan asylums, hospitals, and other needs for the poor in the Holy Land. The board of trustees is traditionally entrusted with the collecting of the funds.

Those who traveled to distant lands in search of these funds are called meshulaḥim.12 In fact, “Recife, the first Jewish community of the Western hemisphere, used to make regular contributions to the Holy Land via Amsterdam…” (Emmanuel 482). Many of the meshulaḥim were rabbinic scholars, men of renowned wisdom and reputable character. Historical letters and synagogue minutes detail the travails of how they acquired funds for the respective charities in the Holy Land and elsewhere. Yaari states, “Thus, it is known to us about emissaries from the Land of Israel that served as rabbis in distant and dispersed communities, from India and Bokhara, until Barbados in the West Indies” (Yaari 131). Such was the case of the Sephardi luminaries that reached North and South America via the Caribbean, namely, Ḥakham Ḥayyim Isaac Carigal and Ḥakham Aharon Yehudah Corcos. According to Carigal, in the seventeenth century, there were only three rabbis in the New World, one each in Jamaica, Suriname, and Curaçao, but none in North America (Lehmann 146).

While emissaries from the Nação were traveling between the European communities and the West Indies in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the archives reveal that Carigal and Corcos were the only two rabbinic emissaries from the Holy Land who embarked on fundraising journeys to the New World. Only two meshulaḥim from the Land of Israel came to the Caribbean in the mid-eighteenth century, as far as I have been able to identify in the communal archives of the Nação in Europe, North America, and the West Indies. The details of the Nação Caribbean communities and the emissaries from the Holy Land who visited them will be the focus of the next section.

Ḥakham Ḥayyim Isaac Carigal

One of the most preeminent and extraordinary meshulaḥim was Ḥakham Ḥayyim Isaac Carigal, born in Ḥebron (15 Tishri 5493, October 4, 1732). According to Ḥakham Emmanuel, his father was Moshe de Abraham Carigal, the prolific author of rabbinical works and the administrator of the yeshiboth Vaz and Drago in Jerusalem. (Emmanuel 482). Isaac studied under the sages of Ḥebron, including: David Melamed, Meir Gedalia, Mordekhay Zoabi, Hayyim Rahamim Bagiaio, Hayyim Yehudah Gomez Patto, and Isaac Ṣedaqah. In 1750, at the age of seventeen, he was ordained by David Melamed (Yaari 580). Others state that, “Having traveled very extensively in the Eastern world and being a man of observation, learning and intelligence, his conversation was highly entertaining and instructive” (Kohut & Parry 124). In twenty-five years of activity, he earned the honor of the emissary who covered more distance than any other of that era (Emmanuel 482).

In 1753, Carigal was sent on his first mission to Egypt as a fundraiser for the Land of Israel. This mission led him to other lands within the Ottoman Empire. He went on his second mission to Western Europe in 1757. Carigal sailed to Curaçao on his third mission in 1761. There, the Ma’amad immediately took him on as rabbi and teacher for the next two years, following Ḥakham de Sola’s death, at the prodigious salary of seven hundred and fifty pesos a year (Emmanuel 1970. 483). He also served as the shoḥet13 of the community and “instructed the housewives how to salt and clean the meat properly” (ibid). His religious tolerance, vast knowledge, and refinement allowed him to reflect honor on Ḥebron and American Jewry, in particular Curaçao, “then the largest, wealthiest community of the Western world” (ibid). Curaçao had long established itself as a donor to the Holy Land. Indeed, Ḥakham Emmanuel asserts:

Curaçao most likely gave funds for the four Holy Cities ever since Ḥakham Pardo’s time (1674-1683). It showed special favor toward Ḥebron where the Patriarchs repose. As a matter of fact, two brotherhoods of Curaçao had as their main object the sending of moneys to Ḥebron. They were the ḥonen Dalim founded before 1726 and the Neweh Ṣedeq founded in 1742 (Emmanuel 1970, 482).

Carigal would take the funds raised back to the Land of Israel at the end of each mission. In 1764, he returned to the places of his second trip, namely Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Nuremberg, Augsburg, and Livorno. Finally, he sailed from Livorno to the Land of Israel, arriving at his home in Ḥebron in August 1764 (Yaari 581).

In 1768, Carigal left Ḥebron on his own mission. He sailed from the port of Jaffa to Marseille. Then he went to Paris, where he stayed for four months. He spent the next two and a half years in England, where he taught at the Beth HaMidrash for a salary. In 1771, he sailed to Jamaica, where he spent a year. Arbell asserts:

Relations with Shearith Israel in New York were very close, as were those between Jamaica and other Spanish-Portuguese Jewish communities in North America - Newport, Savannah, Philadelphia, and Charleston; in the area - Barbados, Curação, Nevis, and Surinam; and in Europe, particularly in London, and North Africa (Arbell 2000, 37).

Delevante also maintains, “The community in Jamaica maintained regular contact with the Holy Land as well as with other Sephardi communities in Amsterdam, London, New York and Curaçao” (Delevante 52). Apparently, Ḥakham Carigal was influential in linking these communities together.

In 1772, Carigal left Jamaica for North America and spent time in Philadelphia, New York, and Newport (Yaari 581). During his stay in Newport, he built a beautiful relationship with Christian theologian and academic Ezra Stiles, who became a close friend of Carigal and described him during the Purim morning service:

He was one of the two persons that stood by the ḥazan14 while the Book of Esther was read. He was dressed in a red Garment with the usual phylacteries and habiliments, the white silk Surplice; he wore a high brown fur Cap, had a long beard. He has the appearance of an ingenious and sensible man (Stiles).

A sense of their friendship can be gained through reading theological and cultural discussions in their correspondence (Dexter 354). Ḥakham Ḥayyim’s journey ended in Barbados. On July 21, 1773, Carigal sailed from Newport to Suriname. After six months there, he left for Barbados, which was the center of trade in the West Indies. One year later, Carigal was appointed as the Rabbi of the K”K Nidḥe Israel, after the passing of Rabbi Meir Cohen-Belifante in 1774. The world lost a great person during the summer of 1777 in Barbados, when Carigal passed (Yaari 582).

Laura Liebman argues that earlier historians note that Carigal was sent to the Americas to raise funds for the Jewish community in Ḥebron. She points out, however, that the religious aspect of his missions has been ignored. She holds that, “Sephardi itinerant rabbis who traveled from the Holy Land to the Diaspora during the eighteenth century had two intertwined missions: to raise funds to support Torah scholars and Jews in the Holy Land and to ensure normative Sephardi religious practice in the Diaspora in the wake of the failed messianic movement of Shabbetai Ṣebi and the ongoing return of anusim to the Sephardi life” (Liebman 78).

She argues further, “That one of the goals of Carigal’s sermon is to meld the disjunctures between the communities’ fractured identities and alliances. Notably, Carigal insists that the identity that unites all of the community (the Kahal) is that of Rabbinic Judaism that supports the Jewish community in the Holy Land” (Liebman 76). Thus, it is important to not limit Carigal’s career to an emissary who collected funds, but to view him as a fundamental figure that worked for the redemption of the Jewish People (ibid. 78).

Ḥakham Aharon Yehudah Corcos

Another emissary who made his way to the Caribbean in order to collect funds was Ḥakham Aharon Yehudah Corcos. The Corcos family was originally from Spain and went to Italy and Morocco after the Expulsion. One of the branches went from Italy to Egypt, then to Jerusalem. Corcos was born in the holy city of Jerusalem. Not much is known about Ḥakham Corcos with the exception that he came from a rabbinic family. According to one source, Corcos sailed to New York via Curaçao, where he arrived on August 12, 1823. He was given a letter written by Reverend Moses Levy Maduro Peixotto, which detailed his predicament. His mission was to collect funds to redeem Corcos’ wife and six children who were captured by the Greeks in Ottoman Turkey (Yaari 712). An entry in the minutes of Shearith Israel (New York) states, “1823…Discourse of M.M. Noah to collect funds for Rabbi Aaron Corcos. $175 made up. Resolved to give him a letter to the Sephardi congregation in Charleston” (Cong. Shearith Israel 167).

A few things can be inferred from this piece of information. Greeks posed a threat to people traveling through the coastlands of Turkey, Corcos had to travel to faraway lands to appeal to the wealthier communities, and he went to visit the Sephardi community in Charleston, South Carolina. The Sephardi community, Beth Elohim in Charleston was founded in 1749; the Hebrew Benevolent Society was formed in 1784. In the initial decades of the nineteenth century, this community was America’s wealthiest. Most of its members came from England and the Caribbean islands and did business as merchants. The outcome for Ḥakham Corcos’ family is not recorded in any known sources.

CONCLUSION

By the nineteenth century, the financial contributions of the Caribbean Sephardim in the ḥaluqah system began to dwindle. Political, social, and economic factors played roles in this situation. Already in the late eighteenth century, the plantation economies that existed a century earlier were not as important. The nineteenth century saw a diminishing of Jewish populations and assimilation of Caribbean Jewry. In the twentieth century, as new states formed in the Caribbean, their economies became dependent on imports from their former motherlands (Harris and Neff 68). Consequently, they were able to neither diversify their economies nor sustain the development of agriculture and industry. This led many Caribbean Sephardim to choose to migrate either to Europe or the United States.

European Jews were emancipated in the mid-nineteenth century and, thus, gained rights to political office and employment in the public sector (Ben-Ur 2020, 223). Prior to 1865, Jamaican Sephardim held a monopoly in agriculture. When they were granted full political rights in 1831, they quickly filled elective seats in the House of Assembly, representing a significant voice in the Parliament. Emancipation also led to high levels of assimilation, such as intermarriage with Christians. In the case of Curaçao, throughout the nineteenth century Jewish men emigrated in search of economic prosperity, thereby leaving many Jewish women without suitable partners (Capriles Goldish 10-11). In Suriname, integration with the non-Jewish society included intermarriage with the majority African-origin Christian population (Ben-Ur 2020, 240).

The end of the nineteenth century saw an influx of Ashkenazim into Jamaica, Barbados, Suriname, and Curaçao. Initially, the communities kept separate. With time, they merged into one. Arbell notes that Caribbean Sephardim began to marry Ashkenazi Jews, thereby losing their Iberian heritage (Arbell 2002, 335; Zohar 291-93). New synagogue bylaws and statutes were drafted in the nineteenth century. Consequently, the established tradition of sending money to Sephardi communities in the Land of Israel was no longer a priority of the hybrid communities.

Caribbean Sephardim had contributed to the ḥaluqah system for over two hundred years. In addition to the changes in the Jewish communities of the Caribbean, the rise of Zionism, the establishment of the State of Israel, and the contemporary use of technology have essentially outdated the ḥaluqah system. Meshulaḥim from the Holy Land were no longer necessary to collect funds on behalf the poor and to support the needy.

Bibliography

Amsterdam City Archives [GAA] 334, Portuguese Jewish Community, folio 19.Amsterdam City Archives [GAA] 334, Portuguese Jewish Community, folio 20.

Amsterdam City Archives [GAA] 334, Portuguese Jewish Community, folio 21.

Andrade, Jacob A.P. M and Basil Oscar Parks. 1941. A Record of the Jews in Jamaica from the English Conquest to the Present Times. Kingston, Jamaica: Jamaica times Ltd.

Arbell, Mordehay. 2002. The Jewish Nation of the Caribbean: The Spanish-Portuguese Jewish Settlements in the Caribbean and the Guianas. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House.

Arbell, Mordehay. 2000. The Portuguese Jews of Jamaica. Kingston, Jamaica: Canoe Press.

August, Thomas. 1987. “An Historical Profile of the Jewish Community of Jamaica.” Jewish Social Studies, 49, 3/4: 303-316.

Avraham, David. 1999.To Come to the Land : Immigration and Settlement in Sixteenth-Century Eretz-Israel. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Ayala, Manuel Josef de. 1990. Diccionario de Gobierno y Legislación de Indias. Madrid: Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamericana.

Ben-Arieh, Y. 1973. “The Process of the Jewish Community’s Emergence from Within Jerusalem’s Walls at the End of the Ottoman Period.” World Union of Jewish Studies, Vol 2: 313-329.

Ben-Ur, Aviva. 2012. Sephardic Jews in America: A Diasporic History. New York: New York University Press.

Berkowitz, Michael. 2004.Nationalism, Zionism and Ethnic Mobilization of the Jews in 1900 and Beyond. Leiden: Brill.

Bettinger-López, Caroline. 2000. Cuban-Jewish Journeys: Searching for Identity, Home, and History in Miami. Knoxville, Tennessee: Univ. of Tennessee Press.

Bissainthe, Jean Ghassman. 2006. Los Judíos en el Destino de Quisqueya. Santo Domingo: Editora Búho.

Bodian, Miriam. 1997. Hebrews of the Portuguese Nation : Conversos and Community in Early Modern Amsterdam. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Capriles Goldish, Josette. 2002. The Girls They Left Behind: Curaçao's Jewish Women in the Nineteenth Century. Waltham: Hadassah-Brandeis Institute.

Congregation Shearith Israel. 1823. Meeting of Congregation Shearith Israel: Hol HaMoed Sukkoth. 22 September.

Davis, N. Darnell. 1909. “Notes on the History of the Jews in Barbados.” American Jewish Historical Society, no. 18: 129-148.

Deive, Carlos Esteban. 1983. Heterodoxia e inquisición en Santo Domingo, 1492-1822. Santo Domingo: Taller.

Dexter, Franklin Bowditch, ed. 1901. The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles: edition under the authority of the corporation of Yale University catalog. hathitrust.org/Record/007925033. Accessed December 11, 2020.

Emmanuel, Isaac Samuel. History of the Jews of the Netherlands Antilles. Cincinnati, OH: American Jewish Archives, 1970.

Emmanuel, Isaac Samuel. 1957. Precious stones of the Jews of Curaçao: Curaçaon Jewry 1656-1957. New York: Bloch.

Fidanque, E. Alvín, et al. 1977. Kol Shearith Israel—Cien Años de Vida Judía en Panamá 1876-1976. Madison: Centennial Book Committee.

Gerber, Jane S. 2014. The Jews in the Caribbean. Portland: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization.

Halper, Jeff. 2019. Between Redemption and Revival: The Jewish Yishuv of Jerusalem in the Nineteenth Century. Abingdon: Routledge.

Harris, Richard L., Jorge Neff. 2008. Capital, Power, and Inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Klich, Ignacio and Jeffrey Lesser. 2013. Arab and Jewish Immigrants in Latin America: Images and Realities. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kohut, George Alexander; Parry, John. 1895. “Early Jewish Literature in America.” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, No. 3, pp. 103-147.

Kritzler, Edward. 2009. Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean: How a Generation of Swashbuckling Jews Carved Out an Empire in the New World in Their Quest for Treasure, Religious Freedom--and Revenge. Chicago: JR Books Ltd.

Lehmann, Matthias. 2014. Emissaries from the Holy Land: the Sephardic Diaspora and the Practice of Pan-Judaism in the Eighteenth Century. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Levy, Avigdor. 1994. The Jews of the Ottoman Empire. Edited with an introduction. Princeton: Darwin Press.

Liebman, Laura. 2009. “From Holy Land to New England Canaan: Rabbi Haim Carigal and Sephardic Itinerant Preaching in the Eighteenth Century.” Early American Literature, 44, 1: 71-93.

Medoff, Rafael and Chaim Waxman. 2009. The A to Z of Zionism. Lanham: Scarecrow Press.

Taylor, Patrick and Frederick I. Case. 2013. The Encyclopedia of Caribbean Religions: Volume 1: A - L; Volume 2: M - Z. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

The Babylonian Talmud. 1997. Schottenstein Edition. New York: Artscroll Mesorah Publications.

The Jewish Bible: Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures -- The New JPS Translation According to the Traditional Hebrew Text: Torah, Nevi'im,Kethuvim. 1985. New York: The Jewish Publication Society.

Yaari, Abraham. 1977. Sheluḥe Erets Yiśrael: Toldot Ha-Sheliḥut Meha-Arets La-Golah Me-Ḥurban Bayit Sheni Ad Ha-Meah Ha-Tesha Eśreh. Yerushalayim: Mosad ha-Rav Ḳuḳ.

Yerushalmi, Yosef Hayim. 1982. “Between Amsterdam and New Amsterdam: The Place of Curaçao and the Caribbean in Early Modern Jewish History.” American Jewish History, Vol. 72, No. 2, pp. 172-192.

Zohar, Zion. 2005. Sephardic & Mizrahi Jewry. New York: New York University Press.

1 Yehonatan Elazar-DeMota was born in Miami, Florida, and comes from a Caribbean-Sephardi family, via the Dominican Republic, Curaçao, Holland, and Iberia. He is an ordained rabbi, shohet, and mohel. He has a Master’s Degree in Latin American and Sephardi studies from Florida International University. Yehonatan is a terminal international law Ph.D candidate at the University of Amsterdam. An earlier, unedited version of this article appears on Academia.com.

2 Hebrew term for forced converts, also known as conversos.

3 Sephardic title for rabbi.

4 Rabbis.

5 Congregations.

6 Rabbinic seminary.

7 Emigration to the Holy Land.

8 Rescue of the captives.

9 Literally man of the community, i.e., the sexton.

10 Non-Muslim citizens.

11 Chief Rabbi.

12 Emissaries.

13 Ritual slaughterer.

14 Cantor.