A Fleeting Moment, A Short-lived Press: Hebrew Printing in Sixteenth

Century Fez1

by Marvin J. Heller2

For the tribes will assemble by the mount, there they will slaughter offerings of righteousness, for by the riches of the sea they will be nourished, and by the treasures concealed in the sand. (Deuteronomy 33:19)

Jewish residence and Jewish history in Fez, in northern Morocco, is both continuous and lengthy. Jewish settlement dates to the early ninth century, continuing to the present day. Although not always positive, since there were periods of extreme oppression, Jewish residence was, more often than not, beneficial to Jews.3 Among the little-known aspects of Fez Jewish history is the existence of a brief press that printed as few as seven to nine books, and perhaps even more between c. 1515 to the early 1520s.4

Fez was founded in 789 by Idrīs I. It became the capital of the kingdom in 808 under Idrīs II. The latter admitted a significant number of Jews, who settled in the al-Funduk al-Yahūdī quarter. They paid an annual tax of 30,000 dinars.5

A positive example of this early Jewish residence in Fez is cited by André N. Chouraqui, quoting Roud el Kartas, who relates that when Idris I assaulted the Jews and Christians in the Maghreb in 789, they were defeated and forced to convert to Islam, despite being ensconced in fortresses. The majority who did not submit were executed. Nevertheless, even the Idrises’ efforts were limited, for according to Ibn Khaldun, Yahya ibn Yahya ben Mohammed the last emir of the elder branch of the Idrises, was attracted to a young Jewish girl of Fez. He attempted to seize her while in her bath. The people of Fez revolted, forcing Yahya to take refuge in the Andalusian quarter of the city. Chouraqui concludes that “this episode shows that the townspeople of Fez were concerned for the welfare of their Jews and of their women, and may be accounted for by the strong Berber influence that remained in the town.”6

Three subsequent events in Fez stand out in vivid contrast to this anecdote; in ca. 987, a portion of the community was deported to Algeria; in 1035, 6,000 Jews were massacred by fanatics who conquered Fez; and in 1068, the Almoravides sacked the city. A century later, in 1165, a new Almohad monarch instituted changes including forced conversion. Among the victims the dayyan R. Judah ha-Kohen ibn Shushan was burned alive for refusing to submit and Maimonides and his family, who were refugees from Spain, left for Egypt. Another source of affliction for the community was the appearance, in about 1127, of a pseudo-messiah, Moses Dari.7 Somewhat later, in 1438, the Jews of Fez were required to live in a separate section of the city known as the Mellah in New Fez.8

All of this notwithstanding, Chouraqui writes that “these crises were of a passing nature” and Fez was, once again, felt to be a safe city so that Jews could settle there, including, as noted above, Maimonides' family. Indeed, apart from the trials of Jewish life, Fez was also a home to Jewish scholars and scholarship with moments of security and even prosperity. Indeed, Chouraqui notes that it was a “center of Jewish learning.” Among the early rabbinic figures who resided in Fez are R. Judah ibn Kuraish (9th century), known as the “father of Hebrew grammar,” R. Dunash ben Labrat (mid 10th century), and R. Judah ben David Hayyuj (c. 945–c. 1000), renowned grammarians. Most celebrated of the sages in Fez was R. Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi.9 Among the later sages is R. Jacob Berab (Beirav, c. 1474–1546) and R. Abraham ben Jacob Saba (d. c. 1508). The former was appointed rabbi of Fez at the age of eighteen. He left for the Middle East several years later, where, in Safed he was involved in the attempt to renew semikhah (ordination for a Sanhedrin) for the first time in several hundred years.10

Photo: W. Mittelholzer, 1932. ETH-Bibliothek Collection, Jewish Houses in the Mellah of Fez.

The expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 saw large-scale immigration to Morocco. The Fez community increased to number as many as 10,000, comprised of “Spanish exiles” (megorashim) and "natives" (toshavim).11 It was to this community that Portuguese émigrés Samuel ben Isaac Nedivot and his son Isaac came. As Abraham J. Karp notes, as the presses of the Iberian Peninsula closed and the Italian presses had not yet achieved eminence, there was a need for Hebrew presses. The time appeared propitious for a new press. The Nedivots who had learned the printer’s craft at the press of Eliezer Toledano in Lisbon founded their Hebrew press in Fez in circa 1516, the first in Africa.12 Indeed, there is a similarity to the works published in both places.13 The press would publish seven to nine titles between 1516 and 1524, including a Sefer Abudarham, Azharot, Hilkhot Rav Alfas, Tur Yoreh De'ah, and several Talmudic tractates, although the attribution of several of the tractates is in question.

Lazarus Goldschmidt, writing in 1948, observes that the similarity of fonts from the two presses, also employed in Salonika, resulted in confusion in identifying the Fez imprints. Morocco was isolated from Europe with the result that the Fez imprints were unknown until recent times. He states that “Hardly half a century has passed since a bookseller discovered a complete copy of the book ABUDARHAM with an exact mention of the place and year of printing: Fez, 1517.”14

Among the first works published by Samuel ben Isaac Nedivot was Sefer Abudarham, a popular classic work on Jewish liturgy and customs. It was composed by R. David ben Joseph Abudarham (14th cent.) of Seville in about 1340. Abudarham is reputed to have been a student of R. Jacob ben Asher (Turim, c. 1270-1340) and a leader of the Jewish community in Toledo.

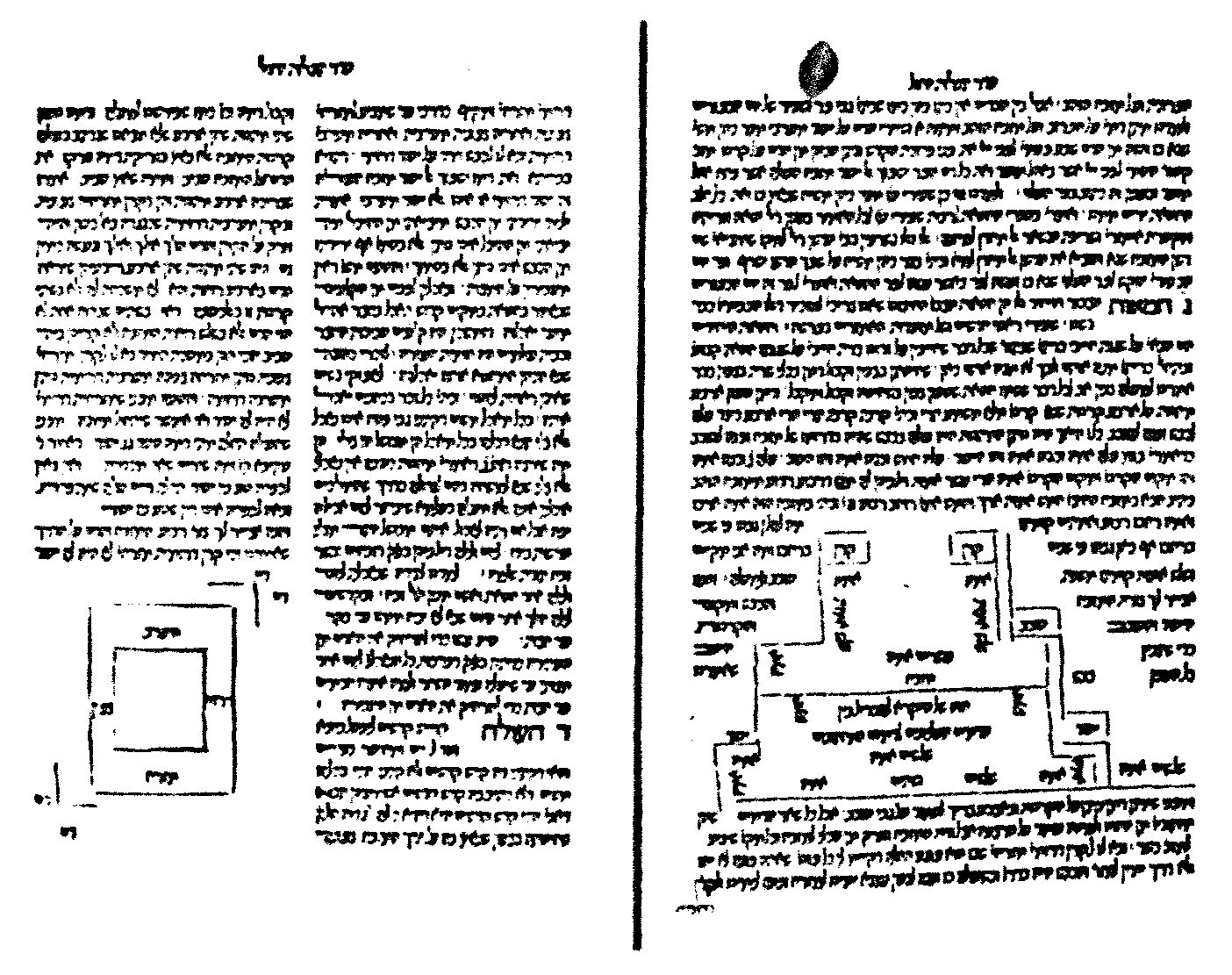

1517, Sefer Abudarham

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Printed as a quarto (40: 170 ff.) by Nedivot, in 1517, it is an exact copy, not only in the font, but also in the beginning and ending of both the pages and the lines on the page, of Eliezer Toledano's 1489 Lisbon edition of that work.15 Nedivot had brought typographical equipment with him from Lisbon to Fez, accounting for the likeness in layout and in the fonts, making the two editions almost indistinguishable. The 1489 Toledano edition served as the copy-text for the typesetters for this printing, the Nedivot Sefer Abudarham being an exact copy of the Toledano edition. It is only in the middle of a long colophon - and it is the sole book printed in Fez with a colophon (extract below), that a short text unquestionably confirms it is a Fez imprint - Nedivot replaces his and his son Isaac’s name, the place of publication, that is, Fez, and the date, Kislev, in the year (5277=1516) עזרה for the information supplied by Toledano.

Sefer Abudarham lacks a title page, Nedivot being concerned that he would not have an adequate supply of paper. Sefer Abudarham informs us in the introduction that he wrote this work because people had become unfamiliar with the words and meanings of prayers and customs. His purpose was to state the laws of Jewish prayer, the reasons for them, and to explain their contents. Based on Talmudic and geonic sources, as well on the works of later commentators, Ashkenazi and Provencal, as well as Sephardic, it is a valuable source of works that have not otherwise survived.16

Sefer Abudarham is one of a number of books known by the name of its author, having no other title. Perhaps in some cases the name proposed by the author was omitted by the copyist, the work becoming known afterwards by the author’s name. Another possibility, appropriate here, is that Abudarham’s intent was to join his commentary on Jewish liturgy to a prayer book, so that it did not require a title, and those who came after called it by his name, Sefer Abudarham.

In describing Sefer Abudarham, Giovanni Bernardo de Rossi writes that it “contains an analysis of the prayers for the whole year, of the Jewish Calendar, of the New Moon, Leap Years, etc. . . It is in manuscript in several libraries. In my library there are likewise MSS. of a commentary, by the same author, on the Haggada, and of the Treatise on Solstices and Equinoxes, both of which I suppose to be extracts of the same work.”17

Sefer Abudarham includes a commentary on the Passover Haggadah, the Jewish calendar, and the order of the weekly Torah readings and haftarot for the year. An unusual feature of the commentary on the Haggadah concerns the blessings over the arb’ah kosot (four cups) of wine at the Pesah Seder. Current Sephardic practice is to make blessings over the first and third cups, whereas the Ashkenazic practice is to make a blessing over each of the four cups. Sefer Abudarham differs from contemporary Sephardic practice, calling for four blessings, reflecting earlier Sephardic custom, changed under the influence of R. Asher ben Jehiel (Rosh, c. 1250-1327).18

Most Fez imprints are quite rare. Another such work, recorded by both Ch. Friedberg and Meir Mordecai Marziano as the first Nedivot publication is R. Isaac ben Reuben al-Bargeloni’s (of Barcelona) Azharot. Friedberg informs us that it was recorded as a unicum in the Bet Midrash Elyon in Berlin.19 Elsewhere Friedberg dates the Fez Azharot as a [1522] publication, the first of fifteen editions of that work.20

Isaac ben Reuben al-Bargeloni (b. 1043) was among the early sages of Barcelona. He was a follower of R. Hanokh ben Moses (d. 1014). and resided in and was a dayyan in Denia until his death. R. Judah ben Barzillai al-Bargeloni (11th-12th century) was among his students and R. Moses ben Nahman (Nahmanides, Ramban, 1194-1270) was a descendant. Al-Bargeloni was a paytan (liturgical poet), author of piyyutim, selihot, and the azharot, which are included in the mahzorim of the communities of North Africa. He also wrote commentaries to tractates of the Talmud, no longer extant.

Azharot are liturgical poems read on Shavuot enumerating the 613 commandments. R. Moses ben Jacob ibn Ezra (c. 1055–after 1135) and R. Judah Al-Harizi, (1165–1225) both paytamim of renown, praise al-Bargeloni’s Azharot.21 Among the most famous of the azharot are those written by R. Solomon ben Judah ibn Gabirol (c. 1021- c. 1057), whose piyyutim are still read and recited to the present.

Another of the Nedivot press’s early works is Yoreh De’ah from R. Jacob ben Asher’s (Ba’al ha-Turim, c. 1270-1340) comprehensive halakhic masterpiece, the Arba’ah Turim. Jacob ben Asher was the son of R. Asher ben Jehiel (Rosh, 1250-1327). Born in Cologne, Jacob left Germany, due to the severe persecution of the Jews, together with his father, eventually resettling in Toledo. Although Jacob served on the rabbinic court in Toledo, he would not accept any wages for his services, nor would he accept an official rabbinic position, preferring to devote his time to study, with the result that he lived a life of privation.22

The Arba’ah Turim is concerned with halakhot that are currently applicable; omitting those inoperative in the absence of the Temple. It is the basis of subsequent codes to the present. Divided into four parts, Yoreh De’ah is the portion dealing with issur ve-hetter (dietary laws), oaths, usury, and mourning.23 The volume measures 30 cm. folio (20: 134 ff.). Nedivot printed a second part of the Arba’ah Turim, Hoshen Mishpat, in 1520.

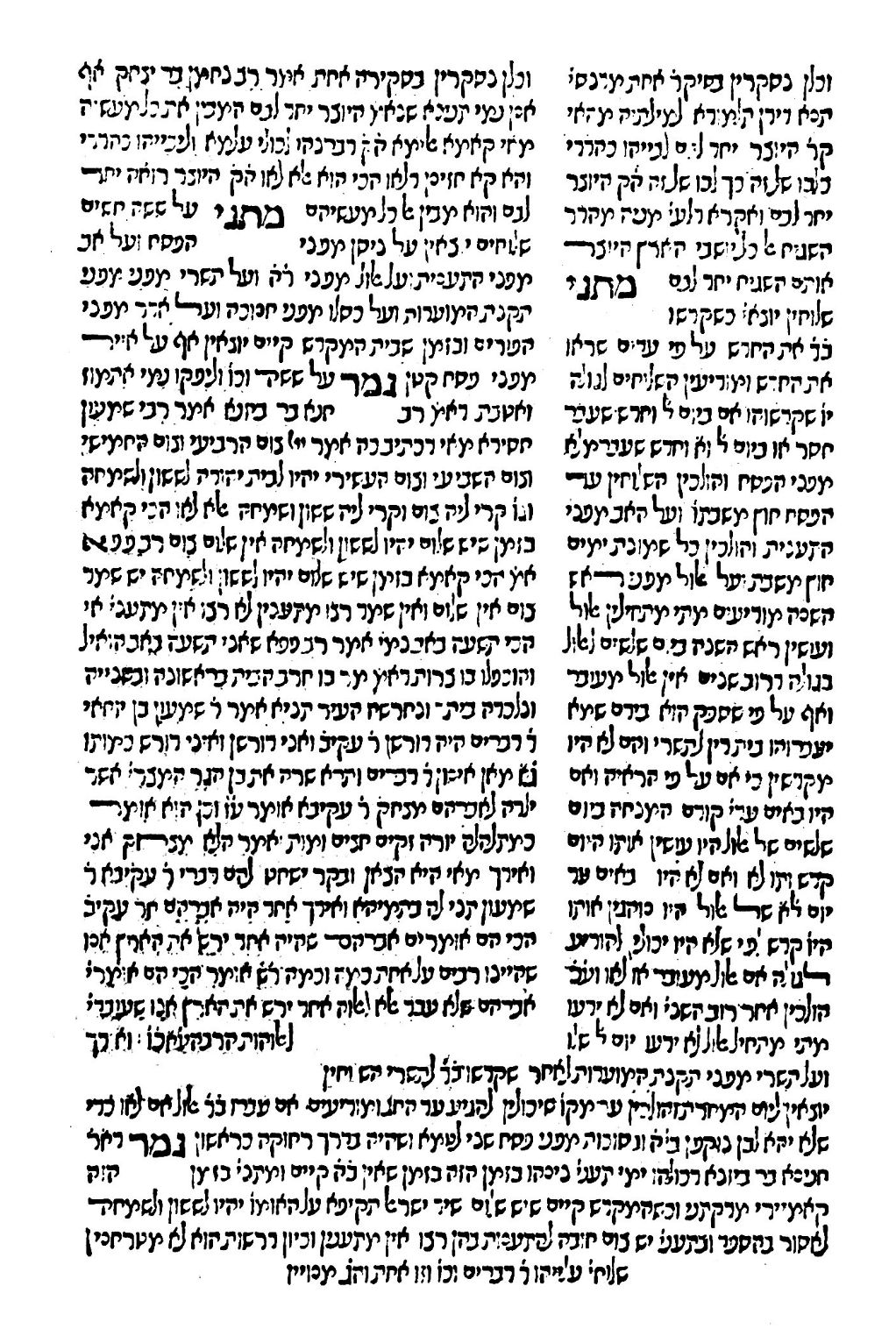

1519, Tur, Yoreh De’ah

Courtesy of Kestenbaum & Company

The Fez Tur Yoreh De’ah is of extreme rarity. Two copies only are recorded, both incomplete, one in the Schocken Library in Jerusalem, and an incomplete copy in the University of Alberta. In addition, small fragments exist elsewhere. The Mehlman Collection in the National Library of Israel has a one leaf fragment and the library of the Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak has a two leaf fragment.

The Thesaurus records this edition of Yoreh De’ah as the first Fez imprint. The above image is from an edition offered at auction by Kestenbaum & Company. The auction catalogue describes it as “ff. 121 (of 134) lacking 34 leaves. Commences from the middle of Siman 5 of the laws of Slaughter (sig. 2:2) and continues through Siman 389 of the laws of Mourning . . .” The asking price was $40,000-$60,000, price realized $50,000.24

Several tractates from the Talmud were printed in Fez. Both Meir Mordecai Marziano and the Thesaurus record tractates Rosh Ha-Shanah, Hullin, and Eruvin as Fez imprints, but the latter, however, gives the location in brackets, that is, as questionable. Friedberg adds Kiddushim but omits Hullin.25

Rosh Ha-Shanah stands out in contrast to other printings of the Talmud, indeed it is a unique tractate, given that its font, that is the letters in which the text is set, are rabbinic (Rashi) rather than the normative square letters. It is questionable whether the Nedivot press had many square letters, as the other Fez titles are also primarily set in rabbinic letters, although in contrast to this tractate the use of such a font in the other titles is not remarkable. Furthermore, the rabbinic letters used by the Nedivot press are a distinctive Sephardic semi-cursive font, which differs from the more common rabbinic letters employed today. The only square letters in the volume are initial letters, for example, indicating the beginning of a Mishnah or Gemara. Another feature of this edition of Rosh Ha-Shanah is the absence of Tosafot. This reflects the Sephardic tradition of learning Rashi and the novellae of R. Moses ben Nahman (Ramban) rather than Tosafot.

Another tractate now considered to be a product of the Nedivot press is Eruvin. Originally thought to be a Salonika imprint from the press of Don Judah Gedaliah, which also employed a like Sephardic font, that attribution was subsequently questioned by several bibliographers, among them Haim Dimitrovsky. He compares Rosh Ha‑Shanah to Nedivot’s edition of the Sefer Abudarham and finds evidence for ascribing both Rosh Ha‑Shanah and Eruvin to the Fez press. He too notes that Rosh Ha‑Shanah is the only tractate in which the text was printed with Rashi letters. According to Dimitrovsky these letters, and the initial large square letters, are identical to the fonts in the Sefer Abudarham.

1516, Tractate Rosh Ha-Shanah

Courtesy of the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary

The tractates also make use of a distinctive mark between sections of the text and within Rashi, an unusual form of abbreviation and of the Tetragrammaton, all also found in the Sefer Abudarham. Rosh Ha‑Shanah has two watermarks, one of which appears in the Sefer Abudarham and the second in the Tur Yorah De'ah printed in Fez. Dimitrovsky also concludes that Rosh Ha‑Shanah preceded the Sefer Abudarham as a comparison of the layout of the pages in Rosh Ha‑Shanah and the Sefer Abudarham, shows greater skill and experience in the latter as opposed to the former.

Dimitrovsky also attributes a fragment of Hullin to Fez. The similarities between this and the other Fez tractates, for example the fonts, the final peh, abbreviations, absence of catchwords, and other marks, justify this attribution. Nevertheless, differences, such as the layout of the page, reflecting the influence of the tractates printed in Soncino and Pesaro, indicate that Hullin was printed later than the other tractates.26

The Thesaurus records also Hilkhot Rav Ashi and Hilkhot Shehita u-Bedika, as [Fez] imprints and both dated [1524]. However, given that they are questionable to begin with and their dates suggest a gap in printing between them and the other Fez imprints we will not address them in this article.

The Nedivot press was forced to close after publishing a small but indeterminate number of titles. The primary reason for the press’s closure was a Spanish prohibition on the sale of paper to the press. It would be almost four hundred years after the closing of the Nedivot press before another Hebrew press opened in Morocco. That press, in Tangier, opened by Solomon ben Hayyun in 1891 began by publishing a weekly, Kol Yisrael.27 It was preceded by the first newspaper in that city in 1870 edited by Ben-Ayon and in 1884 by Le Réveil du Maroc, founded and edited by Levy Cohen.28

Despite the small number of titles printed, Samuel ben Isaac Nedivot together with his son Isaac, for a short interval in time, operated a printing press of substance. Refugees from an oppressive society, they opened a Hebrew press, published attractive and varied works, on liturgy, halakhah, as well as Talmudic tractates, before being forced to close due to circumstances beyond their control. While not well remembered, it is a bright spot in the annals of Hebrew publishing. As we began, we conclude fittingly,

By the riches of the sea they will be nourished, and by the treasures

concealed in the sand.

(Deuteronomy 33:19)

1 I would like to express my appreciation to Eli Genauer for reading this article and for his corrective suggestions.

2 Marvin J. Heller is an award winning author of books and articles on early Hebrew printing and bibliography. Among his books are the Printing the Talmud series, The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book(s): An Abridged Thesaurus, and several collections of articles.

3 https://www.bh.org.il/jewish-community-fez-morocco/

4 Meir Mordecai Marziano, Sefer Bene Melakhim: ve-hu Toldot ha-Sefer ha-Ivri ve Maroko me-Shenat 277 ad Shenat 749 (Jerusalem, 1989), p. 35 [Hebrew]; Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. Listing of Books Printed in Hebrew Letters Since the Beginning of Printing circa 1469 through 1863 II.(Jerusalem, 1993–95), p. 499 [Hebrew].

5 David Corcos, Haim Saadoun, and Ḥayyim J. Cohen, “Fez,” Encyclopaedia Judaica, VII (2007), pp. 6-8.

6 André N. Chouraqui, Between East and West: A History of the Jews in North Africa (Philadelphia, 1968), pp. 38-39.

7 This Moses Dari is not to be confused with Moses ben Abraham Dari (late 12th –early 13th century), a renowned Karaite poet.

8 Museum of the Jewish People - Beit Hatfutsot: https://www.bh.org.il/jewish-community-fez-morocco/; David Corcos, et. al.

9 Chouraqui, p.52, 82-83.

10 A compelling digression: R. Abraham Saba, among the exiles of Spain, first sought refuge in Portugal. The respite was brief, for, in 1497, King Manuel of Portugal ordered the conversion of Portuguese Jewry; Saba then lost his sons to forced baptism, at least one of whom is known to have returned to Judaism. Manuel subsequently ordered the seizure of all Hebrew books. Saba recounts that he lost his extensive library but placed himself in great danger by bringing the manuscripts of his commentary on the Torah, on the Megillahs, Avot, and Zeror ha-Kesef, written in his youth, with him to Lisbon. When he reached that city, local Jews informed him that possession of Hebrew books was considered a capital offense, so that Saba buried his manuscripts under a “green olive tree, fair, full of beautiful fruit.” (Jeremiah Chapter 11:15). For him it, “was more bitter than wormwood, and I called it the tree of weeping, for there I buried that which was more desirable to me than fine gold, my commentary on the Torah and mitzvot, for through them I was comforted for my two sons who were taken involuntarily to be baptized.” Saba was arrested, imprisoned for six months, and pressured to accept baptism. When that failed, Saba was released and permitted to go to Morocco. He eventually settled first in El Qsar el Kebir, ill, as a result of his hardships. When he recovered, Saba was able to rewrite, from memory, with only a Chumash to assist him, most of Zeror ha-Mor. He later moved to Fez, where he completed that work, and rewrote Eshkol ha‑Kofer, his commentary on the books of Esther and Ruth. This account.is well known. R. Hayyim Yosef David Azulai (Hida), who supplements this with the following. After residing in Fez for ten years, Saba traveled to Verona, Italy. En route a storm arose. The captain, in despair, requested Saba to save them and pray for the ship’s safety. He agreed, but on the condition that, if he were to die at sea, the captain should not bury him at sea, but rather take him to a Jewish community for proper burial. The captain agreed, Abraham Saba’s prayers were answered, and the storm abated. Two days later, on the eve of Yom Kippur, Saba died. The captain took his body to Verona, where the Jewish community buried him with great honor. (Shem ha-Gedolim, I (Jerusalem, 1979), pp. 14-15.

11 Concerning the population of both the megorashim and the toshavim see Jane S. Gerber, “The Demography of the Jewish Community of Fez after 1492,” in Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies vol. II pp. 31-42.

12 Abraham J. Karp, From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress (Washington, 1991), pp.15-16.

13 C. B. Friedberg, History of Hebrew Typography in Italy, Spain‑Portugal, and Turkey (Antwerp, 1934, reprint Tel Aviv, 1956), pp. 143-44 [Hebrew].

14 Lazarus Goldschmidt, Hebrew Incunables: A Bibliographical Essay (Oxford, 1948), p. 13.

15 A popular work, Sefer Abudarham was first published in Lisbon in 1489, reprinted in Constantinople (1513), Fez (1517), and reprinted in Venice (1546 and 1566).

16 Shimon Vanunu, Encyclopedia Arzei ha-Levanon. Encyclopedia le-Toldot Geonei ve-Ḥakhmei Yahadut Sefarad ve-ha-Mizraḥ I (Jerusalem, 2006), pp. 425-26 [Hebrew].

17 Giovanni Bernardo de Rossi, Dictionary of Hebrew Authors (Dizionario Storico degli Autori Ebrei e delle Loro Opere), translator Mayer Sulzberger translation, with a prolegomenon by Marvin J. Heller (Lewiston, N. Y., 1999), p. 22.

18 Concerning the Sefer Abudarham and change in the variant customs see Marvin J. Heller “A Note on Medieval Sephardic Practice at the Seder,” Tradition v. 30 n. 3 (1996), pp. 44-50, reprinted in Further Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (Leiden/Boston, 2013), pp. 453-63

19 Friedberg, Italy, p. 143; Marziano, p 12.

20 Ch. B. Friedberg, Bet Eked Sefarim (Tel Aviv, 1951), alef 1433 [Hebrew].

21 Al-Bargeloni (i.e. 'of Barcelona'), Isaac ben Reuben.” Encyclopedia Judaica, I, p. 586: Vanunu, III, p. 1252.

22 Mordechai Margalioth, ed., Encyclopedia of Great Men in Israel III (Tel Aviv, 1986), cols. 842-66 [Hebrew].

23 The other sections of the Arba’ah Turim are Orah Hayyim, laws applicable from rising to retiring for weekdays, Sabbath, and festivals; Even ha-Ezer, matrimonial law, such as divorce and betrothal, as well as other matters relating to women; and Hoshen Mishpat, on civil law, testimony, and other personal and business matters.

24 Kestenbaum & Company, Fine Judaica: Printed Books, Manuscripts and Autograph Letters (May 2nd, 2013), Auction 58 Lot 198.

25 Concerning the tractates discussed in this section see Marvin J. Heller, Printing the Talmud: A History of the Earliest Printed Editions of the Talmud. Brooklyn, 1992, pp.

26 Haim Dimitrovsky, S’ridei Bavli: An Historical and Bibliographical Introduction (Hebrew) (New York, 1979), pp. 44‑45, 68-69 [Hebrew].

27 Marziano, pp. 14, 39.

28 David Corcos, et al., EJ 19, pp. 501-502.