Through the World of Books without a Map: An Ongoing Journey: The Farhi Palace of Damascus, Syria

Reviewed by Bension Varon*

FOR RON...

For Sephardi (Spanish) Jews, in the Last Two Centuries

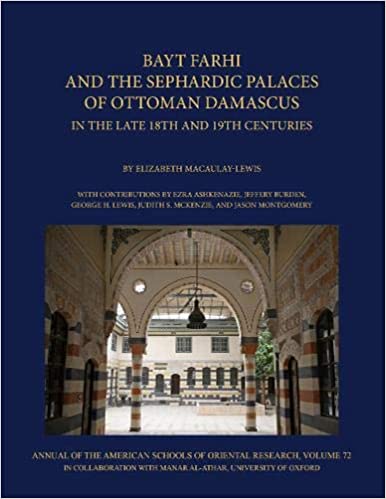

Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis, Bayt Farhi and the Sephardic Palaces of Ottoman Damascus in the Late18th and 19th Centuries, with contributions by Ezra Ashkenazie, Jeffery Burden, George H. Lewis, Judith S. McKenzie, and Jason Montgomery.

Annual of the American School of Oriental Research, Volume 72 in collaboration with Manar Al-Athar, University of Oxford, 2018.

This is not a typical book review. It is, rather, an informal note addressed to you [Ron Kornell] through whom I met my first and only Farhi in the mid-1970s in Paris.1 This odd introduction is prompted by the fact that I have been disappointed by the book. This has been due less to the merits of the book, which are considerable, and more to my unmet expectations. The book presents a comprehensive and scholarly analysis of the subject—a historic Jewish ‘macmansion’. The narrative is 335 pages long and supported by 303 original illustrations, most of them prepared for that purpose.

I had been quite familiar with and attracted by the initiatives of wealthy entrepreneurs, philanthropists, educators, and oligarchs of a broad spectrum to invest in the wellbeing of their less fortunate kin in North Africa, the Middle East (broadly defined), and South and East Asia. I had been familiar with the work of people (a number of whom have been Jewish) like the Rockefellers, the Crémieux, Fords, Soros, and (Fethullah) Gülen in this area. I had been looking forward to letting Macaulay-Lewis and her team fill in the scholarly gap left by others, concerning Sephardim in particular. But this did not happen to the extent I expected.

There is no doubt that the Farhis were Spanish Jews who after the Expulsion and over time reached Syria via Southern Europe, Turkey and Aleppo. Yet, the story Macaulay-Lewis weaves is not strictly speaking a Sephardic story. This is the central point of my note. I also believe that Ron and I were not among the intended audience for Macaulay’s work. (More on this later.) I, nevertheless, and despite my Sephardic core, learned a great deal from it, and I was stimulated by it.

The rest of this paper is in four parts. Part I puts into words both the purpose and coverage of the author(s) work. The next two parts make up the central, substantive part of it. Part II is devoted to the link between the so-called Farhi Palace, Ottoman and Sephardi history and culture, and Part III to the varied strengths and weaknesses of the book. Despite the central place they occupy, Parts II and III barely sketch the contents of Macaulay’s analysis; this is left to other interested readers and researchers to do for themselves. My review ends (Part IV) with observations regarding the contribution of the Farhi book to Sephardi research, which has been in remarkable ascendance. Admittedly, however, it suffers from the same handicap that essays on visual and other arts (including music) and aesthetics do, namely, the challenge of dealing with their subjects, how to critique non-pictorially or without the help of the rainbow, both virtually and figuratively.

Purpose and Coverage

The Farhi House is a mansion in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Damascus built, renovated and maintained by a family of the same name over the last two centuries. The family head or patriarch who took initial steps was Haim Farhi. Like others who did the same in different places and at different times he amassed the political power and material wealth necessary by serving as financial adviser to the ruling governors of the region. The project took some 25 years (1795-1820) to complete, assuming that one ever completes such things. It was aimed to benefit the Farhis’ extended family and had a number of distinctive features. The most striking was its monumental size, which flowed from its style: the multi-functional courtyard style. Its construction overlapped with that of the White House in Washington, DC, 1792-1800 (the comparison stops there), which it dwarfed in size, although the Mount Vernon and George Mason estates would make fairer comparisons on stylistic grounds.

In courtyard construction, the residential buildings surround the courtyard(s) of which the Farhi House had ten, one opening without doors onto another. I am not sure who coined the appellation palace to Farhi House. Macaulay-Lewis’s choice, “Bayt Farhi,” simply means Farhi House in Hebrew. I opted to call it Hacienda, although “compound” would also be appropriate but perhaps unattractive. My choice was influenced by what I read in the book.

The Farhis’ fortunes fluctuated over time, and so did the attention, resources and, indeed, time they could devote to their jewel possession. The property fell into abject neglect at times. It had to undergo several rounds of renovation by the owners, who became too numerous through inheritance and acted like absentee proprietors. Luckily, the family bonds to the place were such that there was often a Farhi pulling for a Farhi shanty house (an admitted over-generalization), if not palace. The result was an incoherent admixture of poorly designed and maintained buildings which drew greater attention to their still poorer surroundings than to themselves. On such occasions, one wished that fewer family members, rather than more, felt the drive to get involved.

Under the circumstances Macaulay-Lewis describes, the option of reconfiguring the estate, finding new uses for it, arose and never died. The most popular one has been conversion to a luxury resort, restaurant or hotel. A series of patchwork renovations have ensued. The last decade in particular saw beehive-like activity in anticipation of or preparation for such a drastic move. The work has involved both exploratory and archival research to preserve authenticity where desired. It has left no issue or concern unaddressed or option not considered. The result has been at times chaotic rather than orderly, with broom-closet-like structures stuck between palatial ones and courtyards. Macaulay-Lewis recounts events after the estate’s last days in Farhi hands, as follows:

The renewed interest in the courtyard houses of Damascus in the late1990s and early 2000s led to a new appreciation of Bayt Farhi. The purchase of the house and its subsequent renovation and conversion into a hotel by Hakam Roukbi, a Syrian born, Paris based architect raised its profile. News of its restoration and conversion appeared in the media. In 2000 Roukbi sold the partially restored house to Ayman Asfari, a London-based Syrian businessman who continued with the hotel conversion until the war. The Asfari family asked me to prepare a coffee table book for the hotel’s guests on the history of the house and its owners, which led to the present more detailed study.

And this is in fact what resulted: a coffee table book of three hundred and thirty glossy-paper pages weighing a full three pounds.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Macaulay-Lewis and her team attacked the task with zeal. The outcome is a highly detailed study, with two exceptions. One was attention to the Farhis themselves, which, in my judgment, was too limited. The thick book includes just one family tree and a meager one, (p.10). The authors call it a partial tree. Where did the family’s financial resources come from? Were there frequent intermarriages or, conversely, family feuds that arose from living together or separately? Macaulay-Lewis et al. write that the Farhi house had a library, a hall dedicated to it. What, if anything, is known about it? Same questions about place of worship and kitchen, based on my experiences with Topkapi and smaller palaces! The reference to the “Service Courtyards” in the last chapter’s title (“The Juwwani, Middle, and Service Courtyards”) seemed to offer an opportunity to admire the owners’ exquisite cooking and eating utensils of Chinese origin like those displayed at the Topkapi now-museum, but this was not the case, as Macaulay-Lewis omitted them.

Etymologists and genealogists usually face problems that are common, starting with the basic one of the origin of names. For this reason, I devoted a whole chapter to my family name in The Tale of a Name,2 my very first attempt at genealogy: it came about largely by consulting with eminent Sephardi scholars, other linguists (including Spanish and Hebrew), and historians. I added native Arabic speakers for the current paper. The effort led to the conclusion that the Farhi surname is related to the notions of comfort, happiness, and ease—Arabic ideal or values?--all connoting good living, as the Farhi founders wished for themselves and others.3

The most serious problem faced by genealogists, like all historians, is the lack of historical information, at least in the desirable reliability and detail. I faced it myself while drafting The Tale of a Name: I simply could not trace my family lineage before the reign of Sultan Mahmut II (1808-1839). Being surrounded by interesting people for most of my life, I transferred my interest to the contemporaries of my kin, whether Varons or not. I adopted the change and the rationale permanently and unhesitatingly because if you cannot go backward in time, go sideways; if you cannot go vertical, go horizontal. This changed the nature and orientation of my genealogical work significantly, even drastically, from biography to cross-cultural comparison with which I am identified. Hence Cultures in Counterpoint.4 Ten years later. I don’t know how common such modifications are, but I look at it as a change in the points of entry into my distant past, not the points of exit from it.

Whether driven by similar considerations or not, Macaulay and her team have given us a study of five Sephardic palaces, not one, which they called “high status houses,” all in Damascus, not just Bayt Farhi. Shall we be disappointed or happy? Time will tell. The houses had names like Bayt Dahdah, Bayt Lisbona, Bayt Stambuli, Bayt Tutah, and Maktab ’Anbar. They are given the thorough architectural treatment in the coffee table book, that is examined from that angle largely or mainly, and the result is repetitive, as a consequence. This is done, moreover, at the expense of digging deeper into Bayt Farhi, for example into its staff and history. It is said that as many as sixty-five family members may have lived at one time there. How about managers, staff? And gardens or stables, even if long gone? Was anything grown there or nearby?

If these were weaknesses, the ‘Farhi Palace Book’, for short, has a number of compensating strengths. The greatest and overarching one is, still, the depth and breadth of the information and analysis presented. The richness of illustrations speaks for itself. The figures are drawn with a precision that connotes obsession and familiarity with the latest technical advances—as if the end-objective were to rebuild an exact copy of Farhi Palace some day or to preserve its memory intact as may be done with the villages and historic monuments being flooded by the construction of dams anywhere in the world. Another strength of the book is the attention to internal design and decorations as time went by in line with changes in the Ottoman environment.

Summing Up

François Farhi, Ron and I have three triangular or two bilateral things in common: western core (all three), French orientation (all three), Sephardic identity or identification (François and I), familiarity with orientalism (François and I), émigré ancestry (all three), Ottoman link (François and I), and multinational experience and leaning (all three). The Spanish angle came only from me, with my Spanish family name and fluency in Judeo-Spanish (Ladino). This is why François introduced the Farhi book to Ron right away, why he in turn passed it on promptly to me, and why we both acquired it without delay.

A potential shared point or convergence of interest was what I could say about the comparative lives and lifestyles of Sephardis in the two Muslim geographic areas. Very little, as it turned out. Macaulay-Lewis et al. are writing for architecture students, albeit mostly Muslim ones, rather than for Sephardi scholars. Their work is steeped in the Arabic culture, ritual, and language, which exacerbated the task of penetrating the highly technical work. One objective in this review had been to present a brief sociological comparison of the two Sephardi communities, Syria’s and Turkey’s, which I could not do because the material on Syria was not there. I shall conclude instead with random observations about the outcome of the work from a personal perspective, as the subject is dear to me.

Spanish Influence. Sephardi means Spanish. What was the extent of Spanish influence in the design and use of Farhi Palace? Very little, as it happens, except for the few Moorish-style arches and fountains. The Farhis did not speak Ladino, nor did the majority of Syrian Sephardim. “The census data of 1892-93 shows a population of 6,265 Jews in Damascus and a comparable number in the province. The Jews of Damascus were almost entirely Arabic-speaking, although they also studied Hebrew in school and learned it for worship. They were well-integrated into Arab-Muslim society, with which they had come to share traditions such as music, food, and material culture" (p. 19). With the exception of some of the communities in Aleppo and Jerusalem, Syrian Jews did not retain Judeo-Spanish as their primary language, Even in Damascus, nearly all of the names for household items were Arabic, whereas they would have been Italian, Greek and French in the rest of the former Ottoman Empire.

Westernization. Though grounded in the Orient, the Farhis had a Western orientation that was ingrained in both their likes and dislikes, both behaviorally and materially. The sartorial choices spoke for more than looks. The women of the family did not wear veils or cover their hair on religious grounds. Besides, when beginning with Mahmud II (first quarter of the 19th century) the Ottoman rulers set a course westward, the Syrian sub- or deputy-rulers kept pace with it, and even led in some artistic and artisanal areas (silverwork, specialized textiles). The models quickly became the westernizing Ottoman rulers. One can see this clearly in the evolution of Syrian wall decorations (sorry I cannot show it). Yet it would be a mistake to call the Farhi Palace western in any way.

Sephardi Connection. The link of the Farhi Palace to the Sephardic past did not go much beyond a whiff of the Alhambra in Granada which had had many courtyards and fountains copied by Haim Farhi and his builders. Macaulay-Lewis, however, provides some links to Sephardi religious practices and traditions that survived to my day. One of these, although not strictly a Sephardic one, is the presence of mezuzot on the doorframes throughout the Farhi Palace. To quote Macaulay-Lewis, “a mezuzah is a parchment scroll inscribed with verses from the Torah, which was affixed to the right doorstop of all rooms in a Jewish home at the top third of a doorframe. A mezuzah was a virtual reminder to the house’s Jewish occupants of God’s command to affix His words to their doorsteps as a constant reference. A mezuzah was also believed to place God’s protection over the house, similar to the way the red doorstep in Egypt on the night of the killing of the firstborn protected the Israelites (93).” When my older sisters were married and established their own homes, my father affixed mezuzot to them with fervor—this was a privilege, not a duty—and with a prayer. Mezuzot are among the most popular souvenirs tourists and visitors carry away from Israel.

Another behavioral trait that Macaulay-Lewis pointed to—one which I can testify to myself —has been a defensive one. Macaulay-Lewis writes, ”The appearance of Bayt Farhi’s exterior and its entry courtyard reflected the common practice of even the most imposing Damascene house having a modest street-side appearance that hid away wealth (p. 1).” Don’t show, don’t show off, was the preferred way.

Conclusions

Ron and François would doubtless want to know how Farhi Palace compares with anything like it, any Sephardic property I have seen in the Middle East or elsewhere. It does not, for there has not been any ... anything of this opulence and size.

The absence of Sephardi character as such in the Farhi Palace or family (at least in my opinion) bears repeating. Unlike North Africa, no evidence of haketia, a mixture of the Arabic and Spanish languages in use there. No equivalent of the popular, beloved thin-dough pastry called boreka No ritualistic, animal-kingdom-like courtship, engagement and arranged marriage tradition among Ottoman Sephardim.as

How about the comparative aesthetics of Farhi Palace? I did not think the so-called palace was beautiful, and it bothered me for a long while to discover why, considering my penchant for Ottoman art and tastes...to discover the absence of the Ottoman heavenly whites, blues and greens on the Ottoman tiles. The dominant colors in Syrian art turned out to be cream, burnt orange and dark brown painted in horizontal bands—not exactly uplifting. Where are the tiles with hints of Chinese and Central Asian and Persian miniatures. I felt like screaming. Not a cedar, not a tulip?

The Farhi Palace’s internal decor did have something original for me in emphasis and abundance, at least: the artistically painted or carved Hebrew or Aramaic quotations from the Torah. They were not unknown in Turkey but not as common because, as my father believed, Hebrew was a holy language that ought to be used sparingly and seriously. I have such a decoration which is limited to a single word, ”Bereshit,” the first word of the Torah meaning: “In the beginning.”

Finally, the picture of Farhi Palace that emerges from Macaulay-Lewis’s book is not one of a place dilapidated and in shambles, to the credit of some Farhis. Should the place be renovated, restored? Yes? But by whom? What is the priority? Where can the means come from? Syria is a war-torn non-country, parts of which are occupied by the United States, Russia, Turkey, the Hezbullah, Iraq, Iran, and Israel (Golan Heights). Every time I write the word restoration, I think of Ibdil, the town on the Syrian-Turkish border which needs reconstruction, not restoration, of its schools, hospitals and housing, and the country that needs to readmit the three to five million people who have left it—a gargantuan task.

* From the editor: this essay dated May 25, 2020, was the last occasional paper that formed part of Ben Varon’s ongoing series, entitled “Through the World of Books without a Map.” One likes to imagine him continuing his journey still, on a higher plane. Ben Varon, who passed away in July 2020, was a loyal supporter and frequent contributor to Sephardic Horizons. Born in Istanbul, he attended Robert College, served in the Turkish armed forces, emigrated to America where he earned degrees in engineering and economics, and followed a career as a World Bank officer, advising various countries on their economic development. He described himself as “a retired economist with varied interests as a writer, including history, biography, bibliophilia, and music.” He maintained his passionate interest in Sephardic culture and often included it among his eclectic writings. He is much missed by his family, colleagues, and friends. The reader will realize that this essay has a somewhat unfinished quality, but shows well a curious and idiosyncratic intelligence at work. Readers can find many photographs of the house on the following website https://www.farhi.org/Documents/Farhi_Houses.htm. With many thanks to Alain Farhi, author of the website. The remaining notes below are Ben Varon’s.

1 For the benefit of third parties, the “you” refers to Ronald (Ron) Kornell, non-Sephardi and non-Jewish, whom I met in January 1965 when I came to the Washington DC metropolitan area to take up a job at the World Bank. We have been close friends and soulmates since. Dr. Macaulay-Lewis, Ph.D. Phil., Oxford University is currently Assistant Professor and Acting Executive Office of the M.A. Program in Liberal Studies (MALS) and director of the MALS track Archeology of the Classical Late Antique and Islamic worlds at Oxford University, and CUNY.

2 The Tale of a Name: Varons across Time and Space. (Fairfax, VA, 2000). https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/bib49794.

3 Reality check always helps. I grew up in Istanbul a few buildings from a six-story rental apartment building called Ferah, comfortable, no better choice of name than this for a residential building.

4 For an essay on and description of this book, see the first issue of Sephardic Horizons.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800