Deborah A. Starr

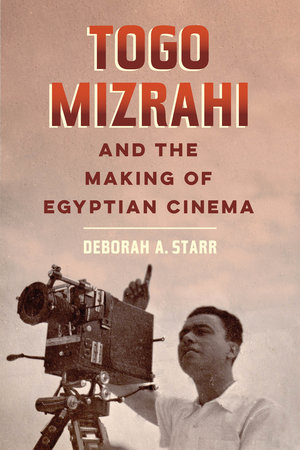

Togo Mizrahi and the Making of Egyptian Cinema

Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2020. ISBN 978-0-520-36620-6

Reviewed by Timothy Riggio Quevillon*

Through his films, Togo Mizrahi repeatedly fashioned himself, and his Jewish protagonists, as children of Egypt. Sometimes this was as unsubtle as the movie posters for his 1933 film Awlad Misr (Children of Egypt) which read “Togo Mizrahi presents Children of Egypt,” with “presents” shown in such small letters as to make it disappear from view upon first glance. In other films, such as Mistreated by Affluence, his assertions were more veiled, opting instead to have Jewish characters be easily mistaken for other Egyptians. This upending of national preconceptions is the primary focus of Deborah Starr’s latest book, Togo Mizrahi and the Making of Egyptian Cinema. Starr, a professor of Near Eastern and Jewish Studies at Cornell, builds upon her previous work on Egyptian literature and culture and adds another dynamic through the examination of popular culture.

Deborah Starr’s book is the latest in a bevy of literature which examines the role of pop culture in examining and forming Jewish identities. Focusing on the work of Togo Mizrahi, a pioneer in Egyptian cinema and an Egyptian Jew with Italian nationality, Starr’s book integrates film analysis with film history to assess the cultural and political implications of Egyptian cinema. Starr argues that Mizrahi’s movies use masquerade and mistaken identity to subvert dominant notions of race, gender, and nationality and to challenge their categorical rigidity. In so doing, Mizrahi’s films offer a hopeful vision of a pluralist Egypt and urged viewers to reconsider the debates over who is Egyptian.

Beyond analyzing Mizrahi’s films through historical critique, Starr also examines what Mizrahi’s success in early-twentieth century Egypt means for existing narratives on the history of Egyptian national cinema. Starr argues that in his day, Togo Mizrahi was viewed by his peers and contemporaneous critics as a consummate professional who was instrumental in establishing a cinema industry in Egypt. However, subsequent generations of film critics and historians who embraced the socialist-influenced, pan-Arab, and anticolonial nationalism espoused by Nasser obscured his historical importance and branded him as a Jew accused of Zionist sympathies. Throughout her book, Starr seeks to recuperate Mizrahi’s image and resuscitate his importance within the nationalist cinema of the day. In so doing, Starr challenges assumptions of who is Egyptian and what makes a movie Egyptian, both ideas that have been linked together throughout the history of Egyptian cinema.

Perhaps the strongest part in Starr’s work is her fourth chapter “Queering the Levantine.” Here, Starr examines Al-Duktur Farahat (Doctor Farahat 1935) and Al-‘Izz Bahdala (Mistreated by Affluence) and argues that the films’ narratives queer both ethno-religious and gender identities simultaneously. Building from the opening shot of Al-‘Izz Bahdala where a Jewish man and a Muslim man wake up in bed together, Starr argues that Mizrahi uses imagery like this as not only a metaphor for ethnic coexistence, but also as a projection of sameness and difference. Through this discussion, Chapter Four excels in demonstrating the ways that Mizrahi’s films challenge Egypt’s heteronormative and homosocial norms. For example, she points to the example of Al-Duktur Farahat’s Tahiya, played by Carioca, who, despite possessing a seemingly normal homosocial relationship with her friend Nona, played by Amina Muhammad, displays romantic desires that challenge the nature of their friendship. By comparing the divergent portrayal of homosocial relationships in these two films, Starr demonstrates that the relationships in Mizrahi’s films often challenged the assumptions of what it meant to be a man or woman in Egyptian society.

Togo Mizrahi and the Making of Egyptian Cinema fits well into the current historiographic refocusing on Sephardic and Mizrahi cinema. Since the rerelease of Ella Shohat’s seminal Israeli Cinema in 2010, a renaissance of critical review of Jewish film and visual media has blossomed. Starr taps into concurrent discussions from Eran Kaplan, Projecting the Nation, – and Yvonne Kozlovsky Golan, Site of Amnesia, which examine the consciousness, or lost consciousness in the case of Kozlovsky Golan, of North African Jews playing out on film. In her addition to this scholarly current, Starr wonderfully recaptures a pre-1948 Egypt in which Jews enjoyed a level of coexistence with their Arab neighbors.

* Timothy Riggio Quevillon, PhD is a Lecturer in History at the University of Houston. His first book examines Jewish nationalism in civil rights struggles through the lens of cousins Moshe and Meir Kahane. His other research focuses on Jewish ethnic and national representation in popular media such as movies, television, video games, and new media.