Italian Fascism and its Treatment of Jews in Libya during World War

II: The Expulsion of Libyan Jews to Tunisia and the Bombardment of La

Marsa

By

Maurice M. Roumani1

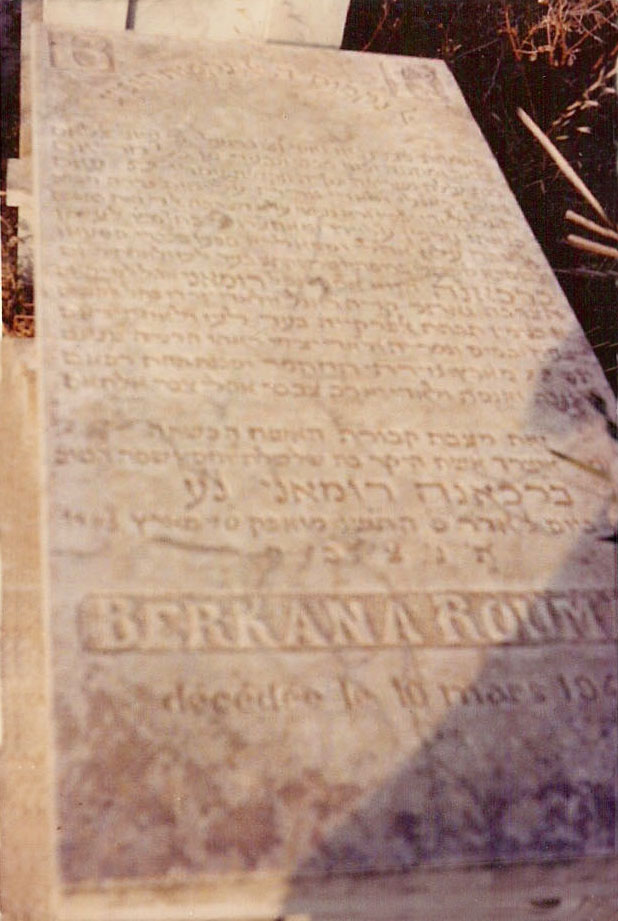

Gravestone in the Jewish Cemetery of Tunis. Photo by Jacques Roumani.

Courtesy of Vivienne Roumani-Denn. Still from the film Last Jews of Libya.

This research article aims to analyze the fate of Libyan Jews, particularly those originating from Benghazi and Cyrenaica, between 1940 and 1944, when Axis and Allied forces were confronting each other in North Africa. What happened to these Jews was set in motion by Mussolini’s anti-Semitic program, applied first on Italian soil and later in Libya. This anti-Semitic program is not unrelated to the motivations for the deportation of foreign Jews to Tunisia and Europe and the internment of the other Jews in camps in Libya. The research traces specific aspects of the operation of deportation of Jews who were French and Tunisian subjects, emphasizing the interventions, fraught with tensions, of various authorities involved: the Italians and the French for the deportation, the French and British governments and Jewish organizations, for the repatriation. Another focus is the bombing of La Marsa, in Tunisia, on March 10, 1943, and its terrible consequences for the Jews who were in the oukala.

The Situation in Libya (1940)

The anti-Semitic laws (termed the ‘Racial Laws’) which Italy passed in 1938, were not immediately applied in Libya, due to Governor Italo Balbo’s policy. Concerned about the economic repercussions of measures affecting the most dynamic component of the colony’s population, Balbo tried to mitigate the impact of the discrimination, even openly opposing Mussolini’s policies, in this and many other aspects.2 Balbo died on June 28, 1940, a few days after Italy entered the war as an ally of Nazi Germany. Two governors followed in quick succession, until General Ettore Bastico was appointed (on July 19, 1941); he addressed various issues, including extending to Libya the anti-Semitism being practiced in Italy, and expelling the foreign population of all religions from the colony for security reasons, and because of the shortage of the food supply in the region.

Removing the population (1941)

Bastico arranged for the departures to start in the second week of September, 1941. They involved approximately 7,000 foreign citizens of various nationalities, among whom there were many Jews. According to Bastico’s report, there were 1,600 Jews in Tripolitania with French or Tunisian citizenship, while the overall estimate for Cyrenaica was just over 2,000 foreign citizens. The Ministry of Italian Africa responded, seeking the opinion of the Interior Ministry and of the Foreign Ministry in a document that no longer spoke of “sfollamento” (removal) but rather of “expulsion of foreigners” from Libya to Italy and their organization in “campi di concentramento” (internment camps). The Interior Ministry cited problems and requested that foreign citizens, deemed to be “dangerous,” be interned in such camps in Libya and that they should stay there.3

Attilio Teruzzi, the Minister of Italian Africa, replied suggesting that the number of internees in Italy be reduced to the 1,900 Anglo-Maltese and the 870 British Jews, since the French and Tunisian citizens (Muslims and Jews) could be sent back to their countries of origin: Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco.4 The expulsion received Mussolini’s approval on Sept. 20, 1941, following the lines suggested by Teruzzi, but the operation turned out to be complex and far from easy.

Hostility toward Jews

The war actions, taking place mainly in the eastern province of Libya, complicated the plan which was being carried out against a background of growing hostility to Jews. Between 1941 and November 1942, Cyrenaica, in particular Benghazi, saw the front changing five times. British forces occupied Benghazi from February 6 to April 3, 1941, yielding to the Italians, who reoccupied it from April 4 until December 23, 1941. The unreliability of the Jews emerges in a report from the General Inspectorate of the Police of Italian Africa dated March 17, 1941, in which Jews are accused of “sending light signals … to the enemy during incursions.”5 Once the Italians returned to Benghazi, the authorities punished the Jews accused of showing favor to the occupying force.6 During the two days between the rapid British retreat and recapture of Benghazi by the Italians, April 3 and 4, 1941, the Italian population took advantage of a vacuum in security, and managed to loot and destroy shops and homes of Jews, and anyone who opposed them was killed.7 Efraim Khalfon, president of the Jewish Community of Benghazi, testified that when they reoccupied the city, the Fascist authorities refrained from punishing those guilty of looting, but arrested about thirty Jews with the accusation of “favoring and passing intelligence to the enemy.”

Accusations against Jews continued in a report from the Italian censorship service dated April 17, 1941, in which in addition to collusion with Allied Forces, the Jews of Benghazi were accused of speculating in prices and thus of arousing the ire of the civilians who sought for revenge.

Negotiations with France (1941)

The Italians began negotiations with the French authorities to send away French subjects (Jews and Muslims) in September 1941, while Cyrenaica was still in Italian hands. But the negotiations for what was diplomatically termed ‘removal’ of French and Tunisian citizens were far from easy and kept the parties busy for almost a year. The French were requesting personal details about the citizens being removed, and identification documents, while for the Italians the issue was extremely urgent. The French requested that the Italians provide an inventory of assets of those being expelled, and that they should be able to bring with them jewelry, money, and other movable assets of value.8

The French expressed their perplexity at the measure, while the Italians responded that the expulsion measure covered all foreigners “without distinction” and that it also involved 20,000 Italian citizens whose activities were not essential for the war effort.9 The Tunisian authorities hoped the process would be carried out with humanitarianism and generosity, guaranteeing ownership rights, completing the inventory of real estate, protecting the interests of those being expelled and allowing transfer of returns on property left in Libya. None of this actually happened: the amount of funds they were allowed to carry was not “adequate for needs over a long period” as the French would have wished, nor were the “valuable objects for personal use.”10 Minister of Finance Revel made a quick end of French requests for transfer of returns and remittances, citing “the laws of war.”

On December 28, the Minister of Trade agreed to the French authorities’ request that the exiles could take with them “jewelry and other valuables” but the amount of money they could take was limited to 450 Italian liras.

On December 24, 1941, Benghazi was again conquered by the allies, but it did not last long. On January 29, 1942, the Germans, followed by the Italians, took the city back.

As a note for the Duce confirms, in January 1942 the negotiations with France were not yet concluded and the French and Tunisian citizens were still in Libya.

The Italian Authorities punish the Jews (1942)

After the second re-conquest of Benghazi, hostility of the Fascist authorities towards Jews became more pronounced. On February 7, 1942, Teruzzi, a close collaborator of Mussolini, wrote two letters, one to Ettore Bastico, the governor of Libya, and the other to Count Ugo Cavallero, the army’s chief of staff. Teruzzi informed them about Mussolini’s firm decision to concentrate all the Jews of Cyrenaica “without exception, in an internment camp, which will be set up using tents in the interior of Tripolitania.” The action had to be taken “due to the behavior of the Jewish group towards the recent British occupation of Cyrenaica.” Teruzzi also communicated that for the time being there were no decisions about the Jews of Tripolitania.11

The exchange of letters points out that the expulsion of the Jews of Libya had become urgent and had to be carried out immediately. Concerning the French and Tunisian citizens, the agreement between the Italian authorities and the French delegation was finally reached on March 14, 1942. The French declared themselves ready to accept their repatriated citizens starting from April 15, 1942, and hoped that they could be “transported in trucks to the border or even to Ben Gardane . . . with a daily frequency of no more than one hundred persons.”

The Italian Consul in Tunis, Silimbani, insisted with the Italian authorities about the importance of protecting the interests of Italian citizens in Tunisia (he mentioned a number of 135,000), including Libyan citizens already living in Tunisia (25,000), but he was never interested in the fate of those French citizens being expelled from Libya.

Meanwhile in Libya the situation seemed rather confused. Despite the agreements made, included in the first contingent to be sent to the internment camp of Giado there were 145 French Jews, who on April 15 had been taken from Barce to be sent to Tripoli. That day the group was at El Coefia waiting to leave for the next destination, Agedabia. The PAI (Italian Africa Police) of Benghazi managed to intervene and obtained a “temporary suspension” of the measure. The group of French Jews was taken back to Barce in the same trucks in which they had gone, but according to the Italian police, there was great discontent because, following the order of removal, they had sold much of their property and they were in dire straits. The Jews were convinced that the removal was in revenge for the fact that about a hundred of them had left Benghazi and followed the British troops during their last retreat. Punishments for Jews accused of collusion with the enemy even included a death sentence for three found guilty by the military tribunal of Benghazi for ‘political looting’. The three Jews (Scialom and Iona Berrebbi, Abramo Bedussa) were executed in Benghazi on June 12, 1942.12

The anti-Jewish legislation in Libya (1942)

The expulsion of the Jews proceeded at the same time as the application of the anti-Jewish laws in Libya. On January 1, 1942 the “Racial Statute for the Jews of Libya” was issued and its twenty-five articles paved the way for discrimination specifically against the Jews in relation to Muslims.13 The measures against Jews followed incrementally during 1942, until the racial laws, in force in Italy since 1938, were fully applied in Libya.

Law No. 1420, “Restricting legal rights of Jews in Libya,” was issued on October 9, 1942, but it was published only on December 17 of that year, when the Italians had definitively lost control of Benghazi and of all of Cyrenaica to the advancing Allied Forces (November 20, 1942).

The deportation to French territories (July-August 1942)

The anti-Jewish legislation sealed the expulsion of foreign citizens (primarily affecting Jews) and the internment of Libyan or Italian-Libyan Jews, which was carried out successfully during 1942. The entire operation regarding French subjects took place in two phases: July 13 to 26, and August 6 to 23. By July 23, 591 Jews from Cyrenaica were first concentrated in Tripoli and then shipped to the border with Tunisia.14 The operation involved “2,542 subjects and Protected French, including 681 Muslims and 1,861 Jews.”15

According to the testimonies of the deportees, the transports consisted of trucks, into which entire families were crowded.

Lieutenant Guarino of the PAI (August 25, 1942) reported that on July 14 the first transport of 203 French and Tunisian Jews from Tripoli to Zuara took place. An internment camp holding 300 people had been set up there.

The groups travelled from Tripoli in special railway coaches that reached Zuara in the evening.16 After customs inspection of luggage and persons, the deportees were loaded the next day into trucks in a column of six or seven. At that point, responsibility for the deportees was taken over by an official of ACORGUERRA, and the convoy was escorted by PAI soldiers (and perhaps by Guarino himself) with the tacit order not to stop until they reached the actual frontier. After a short stop, the convoy continued in Tunisian territory toward the station of Ben Gardane, along bumpy roads on which the vehicles often broke down or got stuck in the sand.

The deportees arrived at Ben Gardane and were placed in a hospital while the bureaucracy proceeded by handling the papers and declarations of assets to the Tunisian authorities. According to the reports of the Tunisian police, the deportees were of of modest means, with many elderly, children, and very few healthy males.17

According to a Tunisian document, the number of Libyans who crossed the frontier at Ben Gardane between July and August 1942 was 2,303: 1,293 Jews and 335 Muslims going to Tunisia; 514 Jews and 55 Muslims going to Algeria; 31 Jews and 75 Muslims travelling to Morocco. Jews identified by the Tunisian police were 1,838.18

From the office of the Joint (American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, AJJDC) in Lisbon, Joseph Schwartz maintained that the number of Libyan Jewish refugees reaching Algeria was 200 families and requested authorization to allocate new resources.19 Six families of Libyan Jews arrived in Morocco and were housed in apartments in Casablanca assisted by the Joint.

Those sent to Tunis or La Marsa amounted to 656 persons. A group of 131 Jews from Benghazi was sent to a camp five kilometers away from Sfax. A second group raised the total near Sfax to 573, while 35 were sent to Sousse and 29 to Gabès. A report from the Tunisian frontier police dated October 1, 1942 confirmed that the deportees from Libya “who arrived in Tunisia about two months ago following an Italian-French agreement, were allowed by the Italian authorities to bring 450 liras each, 1,000 francs and their jewelry.”20

The Situation in Tunisia (1940-1942)

After the signing of the armistice with the Axis forces in 1940, Tunisia was under the control of the Vichy government and its representative, Admiral Estéva, who was appointed governor in July 1940. The French government’s anti-Jewish legislation was applied slowly but relentlessly in the Protectorate of Tunisia.21

The arrival of the Libyan Jews in Tunisia provoked some problems since they were not viewed kindly either by the French authorities or by the Bey, who insisted that the responsibility fall on the local Jewish authorities. Several documents from the American Joint state that the French authorities viewed the Libyan Jews who had arrived in Tunisia as “enemy-aliens,” and for this reason they were placed in internment camps.22

Most of the group that went directly to La Marsa was housed in a single-story building with rooms opening onto a central courtyard (called locally an ‘oukala’), provided by the governing authorities of the Protectorate. The oukala opened directly onto the beach, at La Marsa Plage. Each family occupied one room, with their children, and they lived off their meager personal resources, occasional odd jobs, and the help of the local Jewish community when possible. Food was insufficient, the premises were overcrowded, and sanitary conditions were intolerable.23 Among the refugees, the teachers set up classes for children of various ages.

Libyan Jews who were not housed in the oukala were housed in the hara (Jewish quarter) of Tunis, in La Goulette, or in La Marsa itself.

The Military Campaign in Tunisia (1942-1943)

While the war waged back and forth on the eastern front, the Allies decided to enter the western side of North Africa. Between November 8 and 11, they landed first near Casablanca, then in Algeria, near Oran and Algiers. Operation Torch, led by General Dwight D. Eisenhower, caused the defeat of the Vichy government’s troops in Algeria, due to the collaboration of Admiral D’Arlan, captured in Algiers on the eve of the landing. German troops started landing in Tunisia on November 9, 1942. The Axis forces, maintaining that they had received permission from the Vichy government, continued arriving on November 10. Rommel himself did not arrive in Tunisia until January 25, 1943, but the Einsatzkommando security police under SS Commander Walter Rauff were already active from November 22-24, shortly after the occupation. The Germans applied the same anti-Jewish policies as in other European countries they had invaded, drafting Jews to fortification labor on the front.

In the area of Tunis, there were several camps under German control, including one at El Aouina airport, which was constantly in danger from Allied bombings. Another camp at La Goulette, on the outskirts of Tunis, was under Italian control. The Libyan Jews too, both at Sfax and at La Marsa, were subject to forced labor. All males over eighteen years old were subject to recruitment, often carried out by German soldiers in the depths of the night. A group of Libyan Jewish men was sent from La Marsa to the German camp of Bizerte, which was under heavy bombing, and they were not given permission to return to their families for long periods.24

From the point of view of wartime strategy, the bombings of the airports and ports of Tunisia were intended to prepare the way for the Allied troops advancing from Algeria. The advance faced considerable difficulties due to poor logistics, dispersion of the ground forces and, lastly, the winter weather.25

The American Bombing of La Marsa (March 10, 1943)

By January 24, 1943, all the Italian and German air forces had left Libya and were stationed in Tunisia. Besides El Aouina, near Tunis, the German air force had a landing field about fifteen kilometers from the city, used since November 1942 to bring German troops into Tunisia. The landing field was about three kilometers from La Marsa, near the road that leads to Gammarth.

The Allies bombed La Marsa repeatedly in March and April, 1943, though less than El Aouina. The first bombing of La Marsa, on March 10, 1943, is still recalled as being the worst in terms of civilian casualties.

On March 10, the Fifth Heavy Bombardment Wing organized two simultaneous missions: one against the airfield of La Marsa and the other against El Aouina.

The bombing of El Aouina involved four squadrons of the American 97th Bombardment Group. The forty-four B-17 heavy bombers , so-called ‘flying fortresses’, unloaded over 3,000 fragmentation bombs over the airport.

Regarding La Marsa, American intelligence reported various anti-aircraft positions located not only at the airport, where there were perhaps twenty German planes, but also in town.

The bombing of La Marsa was carried out by the American 301st Bombardment Group of NASAF (Northwest African Strategic Air Force), with its 32nd, 352nd, 353rd, and 419th squadrons. The Americans sent a total of 36 B-17 heavy bombers, each carrying 144 twenty-pound fragmentation bombs. They took off just after 1 p.m. from St. Donat, in Algeria, meeting with their escort at 1:55 pm. Only 34 planes reached La Marsa at 3:17 p.m. All planes returned to base, though not all succeeded in carrying the bombing due to the difficulty of identifying the target. They did manage to drop 4,392 fragmentation bombs. Photos taken during the mission did not prove that the airfield had been effectively hit. It was clear that a number of bombs ended up in the sea, to the north-east of the town, while the crews reported bombs that had fallen to the south and south-east of the airfield and “many points hit” in the town of La Marsa.

The general report on the mission, validated by American intelligence, complained about the lack of photos and information about the target. There were clouds and the escort had to defend the bombers from German counter-attack over El Aouina, but not over La Marsa.

The bombing of La Marsa is recalled by the survivors as a traumatic event that caused at least two hundred dead and numbers of wounded. It was the first time that the Bey’s hometown had been bombed, moreover it happened in the afternoon when many people were lining up in front of the stores to get supplies. The survivors remember that the population was caught off-guard and had no chance to get to safety. The result was a massacre, with dead and wounded strung out along the way to the mosque and to the oukala of La Marsa Plage. Fifty Libyan Jews were killed by the many bombs that fell on the town and near the oukala, including thirteen members of the author’s family, Roumani. The bombing lasted only half an hour.26

The Repatriation of the Libyan Jews (1944)

In June 1943, Joseph Schwartz established an office of the Joint in Tunisia to deal directly with the relief of the local Jewish community.27 The first account on French Jews of Libya deported to Tunisia dates back to July 1943. Elie Gozlan sent a telegram from Algeria to the Joint in New York describing the intolerable condition of Tunisian Jews, which included the 1,000 deportees from Libya, after a year under German occupation. The bombings had left many Jews homeless and the Nazi authorities’ extortions had left the community destitute and in difficult sanitary conditions. Gozlan quickly made a sufficient sum available to meet initial needs. In July 1943, Schwartz stated that both the 400 Jews from Tripoli and Benghazi living in the oukala and the 300 concentrated around Sousse and Sfax were destitute. The Joint took action immediately, approaching the British authorities in Tunisia and Algeria, and the Americans in Washington, to authorize the repatriation of the Libyan Jews. However, the British authorities were seriously concerned about the cost, not so much that of transportation (which would be organized by the army) but that of initial support for people who had lost everything, and whom the British Military Administration in Libya saw as a burden. The Joint declared that it would take responsibility for economic assistance to those being repatriated.

Though the Joint saw repatriation as an issue that should have an immediate and prompt solution, nothing had happened beyond a declaration of intent. Therefore, on August 25, 1943, the Joint organized a joint conference of Americans, French, British and relief organizations, to plan the operation. The French would prepare the list of persons to be repatriated, the British in Tripoli would prepare ground transportation to Tripolitania, while the British in Cairo would take care of sea transportation for the Jews of Cyrenaica, from Sousse or Sfax to Benghazi. The Joint guaranteed their economic support during the journey and for their re-settling in in Libya.

The Libyan Jews were unable to depart by the end of September 1943, because the British had closed the border between Tunisia and Libya “for economic reasons.” The Joint was still confident though that the operation could take place within a short time. At the beginning of December, Herbert Katzki of the Joint wrote to the office in New York that the British authorities had finally authorized the repatriation from Tunisia of 672 Jews from Tripolitania and 63 Jews from Cyrenaica. However, by the end of 1943, none of these French Libyan Jews had returned to Libya, where the Jewish communities were facing hardships and were appealing for help. The approximately 750 Libyans authorized for repatriation and waiting to leave Tunisia could not leave, because the British military authorities still feared the additional burden of supporting destitute people whom the local Jewish community could not help. At the same time the community of Tripoli asked the Joint for $3,600 for supporting those repatriated from Tunisia, since at least 200 people (about 50 families) would be totally dependent on the Jewish community institutions. The Joint emphasized that the funds would be transferred directly to the Jewish community institutions and opposed the demands of the British Military Administration to transfer the funds to Major Gallagher, head of civil affairs in Tripoli, and Lieutenant Bischoff, the officer responsible for relations with the Jewish community.

In February 1944, a report of the Jewish community of Benghazi stated that a thousand Jews from Tunis and Sfax had reached Tripoli. They were actually the same 750 Jews together with 250 Muslims whose departure had been delayed several times.

Part of the Jews of Tripolitania had gone home, but according to the Joint in July 1944, there were still 500 Jews from Libya in Tunisia, and about 550 in Algiers, including those who were previously in Morocco. Transportation was scarce, and many of the transports planned for the month of June had been cancelled. After the cancellation of transport of Libyan Jews from Algeria in July 1944, Julien Gozlan went to Tunisia to reach an agreement with the local authorities for coordinating the operation. They considered sending the deportees from Algeria and Morocco by train to Tunisia, and then back to Libya by car or truck. The Algerian Comité d’Aide aux Réfugiés planned to give them assistance, and house them in the Joint organization’s building in Tunis, the Hafsia school. An initial group of 16 persons left Tunisia on July 10, followed by a second group of 57 persons on July 23, and at the end of July a third group left Tunis (55 people) and another 44 from Sfax. The Joint calculated that there were still 220 Jews in Tunis and 150 in Sfax, while there were still 450 in Algeria, in addition to the 20 from Morocco. The Joint calculated that by mid-September they would all have been able to return to Libya, while Gozlan more prudently predicted that the operation might be completed by the end of 1944.

According to the Joint’s report at the end of November 1944, all the Libyan refugees who had been in Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco had by then been repatriated.

The Libyan Jewish refugees, returning home from the French territories of North Africa, after three years of absence and totally lacking in resources, continued receiving assistance from the Joint programs in Libya.

Conclusions

The research confirms what preceding studies had suggested, i.e. that the expulsion policy was motivated by anti-Semitism. The war on the soil of North Africa, in particular in Libya, inflicted unprecedented hardship on the Jewish community, especially that of Cyrenaica, hardship that evokes what happened to fellow Jews in Europe.

1 Maurice M. Roumani is professor emeritus of Political Science and the Middle East at Ben Gurion University of the Negev, where he is the founding director of the J. R. Elyachar Center for Studies in Sephardic Heritage. He is a leading expert on Libyan Jewish history and has published extensively on Jews from Arab countries, ethnic relations, and migration. His many publications include The Jews of Libya: Coexistence, Persecution, Resettlement (Sussex Academic Press, 2008), lately translated into Italian and Hebrew. He taught at American and Italian universities and serves on the editorial boards of Italian and Israeli journals. Translated by Judith Roumani.

2 Renzo De Felice, Ebrei in un paese arabo (Bologna: Il Mulino, 1978), p. 261ff. Jews in an Arab Land: Libya, 1835-1970, trans. Judith Roumani (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985), pp. 143-167.

3 Document No. 442/25694 (September 13, 1941). ACS (Archivio Centrale di Stato), Ministero dell’Interno, Direzione Generale di Pubblica Sicurezza, Divisione Affari Generali e Riservati, Archivio Generale (1870-1958), Massime, Busta 105.

4 September 18, 1941 and September 21, 1941. Ibid.

5 ACS, Ministero dell’Africa Italiana, Direzione Generale Affari Politici, busta 14.

6 A report identifies 28 people in a photograph applauding the passing British troops in the municipal square of Benghazi. There are 15 Jews, all identified by first and last names: 2 British, 9 French, 3 Libyan, and one Italian Jew. The “nine French Jews and the three Libyan Jews collaborated and showed ‘feelings of sympathy to the British’. Eight of the nine French Jews followed the British in their retreat.” ACS, Ministero dell’Africa Italiana, Direzione Generale Affari Politici, busta 7.

7 Maurice M. Roumani, The Jews of Libya: Coexistence, Persecution, Resettlement (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press 2008), p. 29, and De Felice, Ebrei in un paese arabo, p. 272 and note 26, p. 282 , Jews in an Arab Land, p. 179 and p. 359, note 27. Efraim Khalfon, president of the Jewish community of Benghazi, described the phases of looting that Italians carried out against the shops, homes and synagogues of the Jews, including the murder of two Jews. See note 12 hereafter.

8 Letter from Admiral Duplat, October 10, 1941. ACS, Ministero dell’Interno, Direzione Generale Pubblica Sicurezza, Divisione Affari Generali e Riservati, Archivio Generale (1870-1058), Massime, Busta 105, Nos. 18585, 18586, 18587.

9 Ibid., No. 18585, p. 2. On the figure of the Consul General Giacomo Silimbani, see Daniel Carpi, The Italian Authorities and the Jews of France and Tunisia during the Second World War (in Hebrew) (Jerusalem: Shazar Center, 1993), p. 240 ff.

10 The document is referred to in a letter of October 21, 1941 from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the Interior Ministry. Central State Archives, Interior Ministry, Direzione Generale Pubblica Sicurezza, Divisione Affari generalie riservati, Archivio generale (1870-1958), Massime, Busta 105.

11 The two documents may be found at the ASSME (Archivio Storico dello Stato Maggiore dell’Esercito), Fondo N11, Diari Storici Seconda Guerra Mondiale, Fascicolo 12/3/4, Ministero dell’Africa Italiana 1942, no. 3575. See also Roumani, The Jews of Libya, p. 28 and note 76, p. 245.

12 The information on the Benghazi residents who followed the British troops is taken from the report by Efraim Khalfon, who states that they almost all returned to Benghazi by the end of 1943. Among them was Angelina Gabso, who had been sentenced by the special tribunal to 24 years of imprisonment due to her “political defeatism . . . insulting the Italian nation.” The sentence was not carried out, nor was the death sentence which had been passed on the same occasion on Abramo Arbib for “favoring the enemy” and other crimes. ACS, Ministero dell’Africa italiana, Comando Generale della PAI, no. 3728 (October 26, 1941), nos. 3687 and 3689 (March 17, 1942).

13 See Liliana Picciotto, Gli "ebrei di Libia sotto la dominazione italiana", in Ebraismo e rapporti con le culture del Mediterraneo nei secolo XVIII-XX (Firenze: Giuntina 2003), pp. 92-93.

14 For precise numbers see Roumani, The Jews of Libya, p. 31.

15 Lt. A. Guarino, Relazione sul servizio di sfollamento dei sudditi e protetti francesi dalla Libia in Tunisia, luglio-agosto 1942=XX (August 25, 1942).

16 Lt. A. Guarino and PAI military were there to witness all operations in Zuara. Ibid., p. 1.

17 Habib Kazdaghli, "Immigrations des juifs de Tripolitaine vers la Tunisie (1936-1948)", in La Bienvenue et l’adieu: Migrants juifs et musulmans au Maghreb (XV-XX siècles), vol. 2 (Casablanca: Karthala 2012), p. 33.

18 Ibid., p. 30. Since we do not have lists of names, the discrepancy has yet to be explained.

19 Telegram (August 28, 1942). JDC Archives, Records of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, 1933-1944, File 437.

20 Kazdaghli, Immigrations des juifs de Tripolitaine, p. 33.

21 Jacques Sabille, Les Juifs de Tunisie sous Vichy et l’occupation (Paris: Editions du Centre, 1954), p. 27. Also Carpi, The Italian Authorities and the Jews, p. 248 ff.; Paul Sebag, Histoire des Juifs de Tunisie des origines à nos jours (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1991), p. 222 ff.

22 Kazdaghli, "Immigrations des juifs de Tripolitaine, p. 35 ff. According to Daniel Carpi, Between Mussolini and Hitler: The Jews and the Italian Authorities" in France and Tunisia (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1994), p. 216, the Tunisian Jewish community welcomed the newcomers with open arms. Information from Fascist sources gives us a more nuanced picture of strong tensions between French Jews and Italian Jews. After the liberation of Tunisia, the Allies kept the Libyan Jews in the same camps because they considered them citizens of an enemy country. JDC Archives, Records of the New York Office of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee 1933-1944, File 23, “Minute of the Meeting of the Executive” (September 22, 1943); File 434, “News of the Joint” (November 5, 1943).

23 Testimony of Mino Tammam, deported to Tunisia with his parents and brothers and sisters in the oukala of La Marsa.

24 Testimony of Mino Tammam.

25 Bruce Allan Watson, Exit Rommel: The Tunisian Campaign, 1942-1943 (Westport: Praeger, 1999), p. 65.

26 Other accounts from survivors suggest the oukala was the site of a skirmish between Allied and German planes, or that it was targeted because it was mistaken for the German Kommandatur of La Marsa (not far away, at the Hotel Zephyr), or by mistake, in an effort not to hit the nearby synagogue. These hypotheses are contradicted by the documents.

27 Local sections were later established in all the towns of Tunisia where there was a Jewish community in order to manage effectively the relief operations. In January 1944, the committee was headed by Paul Ghez. JDC Archives, Records of the New York Office of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee 1933-1944, File 119, “Discussion with Mr. Herbert Katzki re Accountings from Committees Subsidized by the JDC” (January 28, 1944).