When the Waters of the Mediterranean Parted: Jewish Libya and the Trajectory of Escape

By

Danielle Willard-Kyle1

Cloaked under a veil of secrecy, ignored by the international press, a strange, mysterious migration is taking place from one to another shore of the Mediterranean…This flow is continuing, unrelentingly. Small parties manage to cross the comparatively narrow, but often quite rough stretch of waters, in sailing boats and small motor launches. Larger groups use fishing trawlers, tugs and other crafts. This new brand of Displaced Persons are Jews who try to escape from the Anglo-Arab regime which for the last six years has prevailed in Lybia [sic].2

Since the end of World War II in 1945, Jews from Eastern and Central Europe had viewed Italy as the thoroughfare to British Mandatory Palestine/Israel.3 Although blockades and quotas had significantly prolonged their tenure in Italian Displaced Persons (DP) camps—camps set up by the Allied Forces and the United Nations in Germany, Austria, and Italy to handle the refugee crisis caused by the war—by 1949 many had made their way to Israel. Jewish refugees from North Africa were also hoping to follow the same trajectory. The experiences of Jews in postwar Libya were inextricably linked to their time as colonial subjects of Italy. The double-edged sword of racism and antisemitism created a dual burden for Jews in Italian-run Libya. Yet, despite this weighted situation, several thousand Libyan Jews still decided to use Italy as the byway to Israel. Postwar relations between Jewish Libyans and their non-Jewish Libyan neighbors and between the Jews and the British Military Administration (BMA) were tense at best. This tension erupted into violence, which sparked the mass exodus of nearly the entire Jewish population to Israel.

This paper examines the choice of a minority in the Libyan Jewish community to travel to Italy as an escape route to Israel following the 1948 riots. These were individuals, families, and small groups (often of youths) who paid smugglers or relied on the direct intervention of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) to help them with this “mysterious migration” out of Libya. It looks first at the DP camps and the legacy of Fascism more broadly in Italy and Libya. It then demonstrates how the interweaving of support from various organizations and agencies made the journey of these Libyan Jewish migrants possible and ultimately enabled them to continue to Israel, despite their not acquiring the proper paperwork or refugee status.

Italy: Displaced Persons Camps and Fascism

In total, nearly 50,000 non-Italian Jewish refugees entered Italy from the north and from the south between summer 1945 and the end of 1951.4 The majority of these foreign Jews came primarily from Eastern and Central Europe, fleeing the continued antisemitism of their home countries and the dismal conditions of the DP camps in Austria and Germany. A smaller number of refugees arrived from North Africa, escaping violence in their home countries. After their arrival in Italy, refugees entered transit camps spread throughout the country. There were at least thirty-five DP Camps and ninety-seven hachsharot (agricultural training centers) in Italy in the first six years after the war, although not all were active the entire time and their sizes varied greatly.5 These temporary accommodations were often former concentration and internment camps, as well as larger buildings such as army barracks, schools, houses, and even a film studio requisitioned by the Allies. British and American Armed Forces were largely responsible for the initial setup of the camps in Italy. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), and its successor the International Refugee Organization (IRO), were primarily tasked with registering, providing care and maintenance including food, clothing, shelter, and financial resources, and repatriating and later resettling DPs.

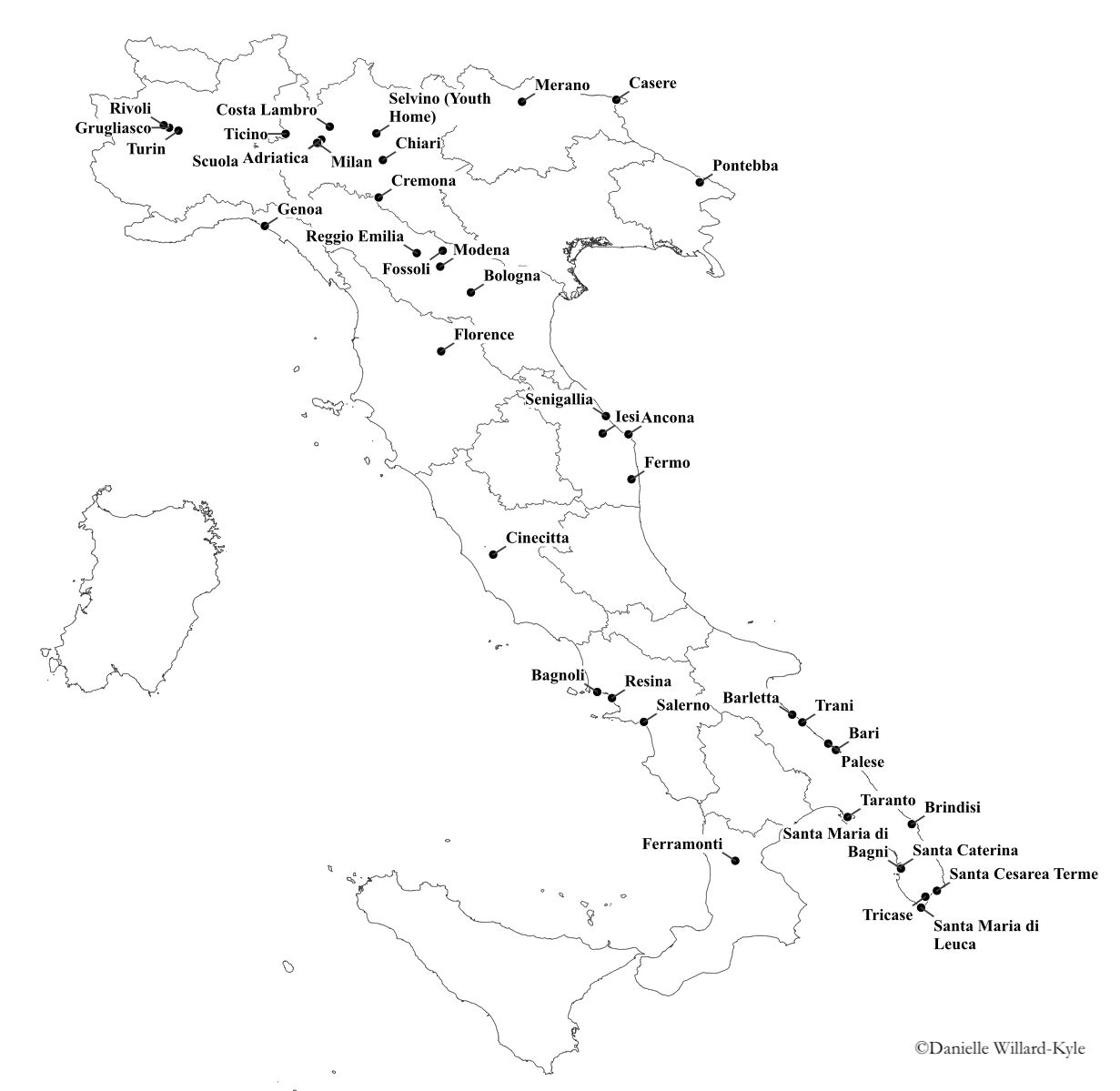

Map of Displaced Persons Camps in Italy. Created by Danielle Willard-Kyle.

Italy’s own complicated history with antisemitism, especially during the Fascist period, offers insight into why Jewish refugees chose to travel to Italy in the first place. Italian policy toward the Jews during the war had varied depending on who was in control and when. The Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini’s 1938 racial decrees stripped all Jews of civil rights and excluded them from public office and higher education. These laws were implemented unevenly at first, which encouraged many German and Austrian Jews who were trying to escape from the Nazis to enter Italy; but after Mussolini declared war, they were stuck. By early 1943, nearly all of these foreign Jews were interned in small towns or in one of the roughly fifty concentration camps in Italy, where they were often forced to work but were not deported.6 The antifascist coup of 1943, however, quickly changed things for both foreign and Italian Jews, as leaders ousted Mussolini and surrendered to the Allies.7 Left vulnerable to attack by an ill-timed surrender and an unprepared Allied force, northern and central Italy were swiftly overtaken by the Germans, who returned Mussolini to power. The Nazis and Fascists then began the deportations of all Jews, foreign and Italian, the most famous of which was the raid in Rome.8 Despite this turn of events, by the end of the war Italy had the second-highest Jewish survival rate in all occupied Europe.

Mussolini’s racial policies did not only apply in Italy, however, but also in its colony, Libya. Libya came under Italian control in 1911 after Italy seized the region from the Ottomans.9 Local resistance under Omar al-Mukhtar began in the 1920s but was eventually crushed following the execution of al-Mukhtar in 1931. Mussolini attempted a process of greater Italian settlement in Libya during the 1930s, as he intended to incorporate the colony into a “Greater Italy;” under Fascist control, the number of Italians who settled in Libya more than doubled, reaching nearly 120,000 on the eve of World War II.10 Jews had lived in Libya for thousands of years, residing primarily in the province of Tripoli (where they comprised nineteen percent of the population) and to a lesser degree in the provinces of Misrata and Benghazi. When Libya became an Italian colony, there were approximately 21,000 Jews in the country; by 1939, Libyan Jews numbered 30,387, just over three percent of the total population.11 Mussolini enacted unprecedented racial laws in Libya in September 1938 that applied to both Italy and Libya. These laws, among other things, expelled Jews from public schooling, forbade “mixed marriages,” and stripped them of their Italian citizenship.12 In 1942-3, the Allies pushed the Italians out of Libya and divided the country under British and French control. Libya finally gained its independence in 1951 under King Idris al-Sanusi.13

Jewish Libyans and the Fight to Leave

In the immediate postwar period, Libyan Jews who had been deported to Bergen-Belsen often made their way home to Libya via train and then boat from Italy.14 In 1945, these North African Jewish survivors were given passage back to their home country via Italy, generally by the Allied Forces or UNRRA whose policies favored repatriation; they did not stay in Italy long. Between 1945 and June 1948, records show that a very small number of Libyan Jewish individuals arrived in Italy hoping to make their way to British Mandatory Palestine. The Italian branch of the Zionist youth organization HeHalutz (or HeChalutz, “Pioneer”), for example, described the arrival of four Tripolitanian youths to Naples in August 1947 who were sent to the hachshara in Cevoli near Pisa and presumably on to Palestine.15

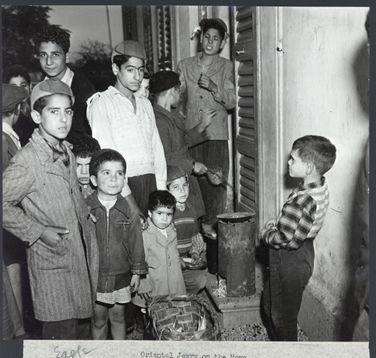

"Italy, circa 1949; A group of Jewish children from Tripoli, still dressed in the rags they arrived in a few days before on a clandestine ship" Image courtesy of the JDC Archives. Reference code: NY_15518.

"Italy, circa 1949; A group of Jewish children from Tripoli, still dressed in the rags they arrived in a few days before on a clandestine ship" Image courtesy of the JDC Archives. Reference code: NY_15518.An American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) report from 1948 marks a shift as it stated that “towards the end of [September] a new element appeared [in the Italian DP camps], in that Jewish refugees from Tripoli were arriving on the shores of Italy in increasing numbers.”16 From late 1948 through mid-1949, larger groups of Libyan Jews, most frequently children accompanied by a few caretakers, arrived in Italy, most through the direct intervention of the JDC and the World Jewish Congress (WJC). Precise numbers are not available, but according to the records of the WJC and the JDC, it appears that between 3,000 and 5,000 Jewish individuals from Libya immigrated first to Italy and then on to Palestine/Israel between 1947 and 1949. During the latter half of 1949 alone, at least 5,000 DPs from North Africa, which included DPs from both Libya and Egypt, made their way through the Italian DP camps; seventy percent of these ultimately emigrated to Israel from Italian ports while the remaining thirty percent were sent to Marseille for further medical recuperation before they could go on to Israel.17

The pogroms in Tripoli and the surrounding region, in particular the second set of riots that occurred in June 1948, appear to have been a turning point for many Libyan Jews who then sought to make life elsewhere. These pogroms were largely motivated by anti-Zionist attitudes amongst the non-Jewish Libyan population sparked by events in the newly founded state of Israel. The violence carried out by the local Arab population that killed over one hundred and thirty individuals and destroyed numerous businesses heightened tensions along racial lines and created an untenable economic situation for the Jewish community so recently devastated by the racial laws and internment, not to mention wartime bombardments. Writing a few months after the pogrom, in September 1948, Roberto Arbib, former president of the Maccabi Club in Tripoli, claimed that because of the British, life in Libya was “becoming more difficult day by day and nearly impossible.”18 They needed assistance and they needed to leave. A local reporter describing the aftermath of the 1948 pogrom proclaimed that “The slogan of every Jew without exception is now ‘to go away,’ irrespective of destination. This is the only goal of every Jew here. They expect in advance to suffer hunger, to abandon their property and their friends, their native country—in order not to become a victim, not to be suddenly slaughtered or burned alive.”19 The Unione delle comunità israelitiche italiane (Union of Italian Jewish Communities, UCII) reported in November 1948 that they were supportive of this goal to leave: “Our brethren do not intend to continue to live in the current dangerous conditions, and we are trying to do what we can to help them.”20

Yet until February 2, 1949, Jews were also not free to leave Libya. Roberto Arbib wrote to the UCII in Rome that life in Libya was becoming unbearable: “We are poorly treated by the British military government and by the Tripoli Arabs, yet at the same time neither one nor the other wants us to abandon the Libyan territory. The moral of the story is that ‘they are holding us hostage’ for an end that is not unknown to us.”21 As late as January 19, 1949, Lillo Arbib, president of the Jewish Community of Tripolitania during the 1948 riots, wrote that “Jews are still not allowed to have a passport and the emigration is still very difficult.”22 Advocating on behalf of Libyan Jews, the Italian president of the UCII stressed to the Director General of the Ministry of Foreign Political Affairs in Italy that “an intervention by the Italian government with the British authorities is required so that they allow Jews to leave Tripolitania.”23 British authorities were reluctant to let Jews leave Libya because they knew most would resettle in Israel and they feared that Jewish migrants would upset the balance there. They argued that “to allow Jews of military age to proceed to Palestine would be a breach of the Security Council’s truce resolution.”24 The UN Security Council resolutions regarding the question of Palestine had called for all persons and organizations to “refrain from bringing and from assisting and encouraging the entry into Palestine of armed bands and fighting personnel, groups and individuals;” 25 the BMA worried that allowing the free exit of Jews from Libya to Israel would be disregarding this order. The BMA was finally convinced to allow Jews to leave Libya only after Great Britain de facto recognized the State of Israel on January 30, 1949.26

In a letter to the WJC, Fritz Becker of the UCII explained the two most frequent ways Jews emigrated from Libya: through what he called “clandestine expatriation” or by obtaining “exit/entry permits through pretext.”27 Using the resources of the JDC, the WJC, the UCII, and the Jewish Agency, Libyan Jews immigrated to Israel via Italy smuggled on fishing boats without papers or sailed on larger boats after receiving false papers. These papers were drawn up under a variety of false pretenses such as claiming to be going on a business trip or continuing religious schooling or needing to receive medical care in Italy. Sixty-five Libyan youth aged twelve to seventeen, for instance, received papers from both the BMA and the Italian authorities in August 1948, to study at the rabbinical college in Rome.28 But when the Ministero dell’Africa Italiana followed up on their arrival in October, he found that instead of enrolling in rabbinical school, the youths had been taken to a DP hachshara or training center in Genazzano just outside Rome; the youths had intended to travel to Italy as a path onward to Israel from the beginning. 29

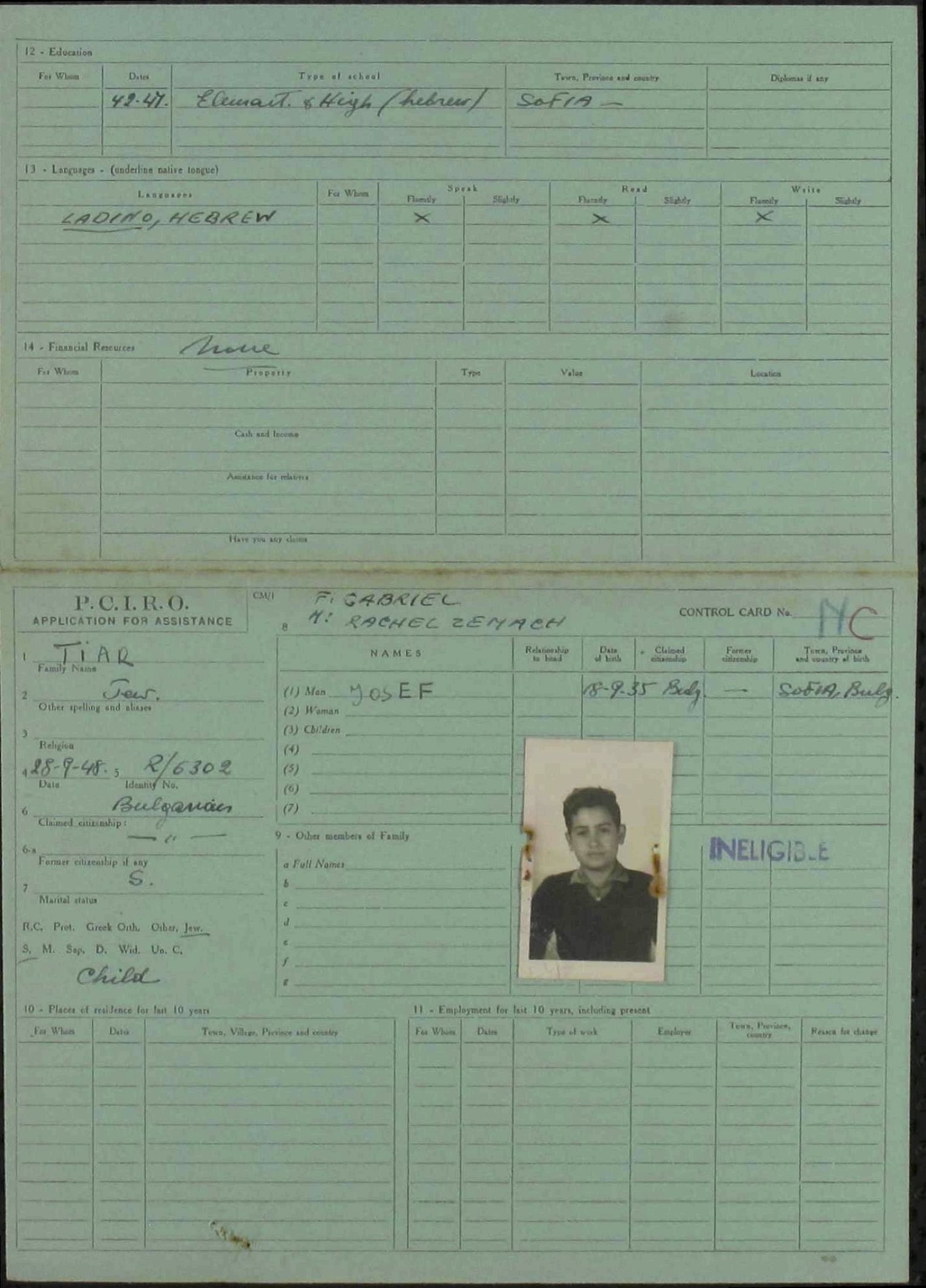

IRO document from "Josef Tiar" aka Josef Tajar.

CM/1 Form for Josef Tajar, 3.2.1.2/80523447/International Tracing Service (ITS) Digital Archive, USHMM.

IRO document from "Josef Tiar" aka Josef Tajar.

CM/1 Form for Josef Tajar, 3.2.1.2/80523447/International Tracing Service (ITS) Digital Archive, USHMM.Upon arrival in Italy, many Libyan Jews claimed partnership with the JDC or with the Jewish Agency. Some lied to the IRO, hoping to expedite their cases and receive eligibility for resettlement aid, as their intent was to leave the country as soon as possible. The case of Josef Tajar offers some insight into arrivals in 1948. Josef Tajar was born September 8, 1935, in Tripoli to Jewish parents. His parents who were still in Tripoli sent him to Italy “because of racial persecution and because they wanted to send him to Israel,” and claimed they had an agreement with the JDC to help him. 30 He arrived in a fishing boat with a small group of others in September 1948. But when the boat arrived in Naples, his group leader confiscated all of his identification documents and told him to tell the IRO he was from Bulgaria, not Tripoli. When interviewed nine days later by the IRO in the Genazzano hachshara, Tajar told them he was “Josef Tiar” from Sofia, Bulgaria, and that he was simply trying to reconnect with his parents and siblings who were already in Israel. Originally believed, he is classified as “eligible” for resettlement and placed on the list for Israel with the Consulate in Rome. But then something went wrong with the plan: the IRO discovered he was actually from Libya, so he was taken off the list, marked “ineligible,” and transferred to the camp in Salerno where he would wait until at least April 1949.31 European Jews had rights and fit into categories for assistance in leaving Italy, as well as aid in Italy that their North African counterparts did not have.

Not all authorities, however, worked against the interests of the Libyans. Records also show that at least some Italian authorities were aware of “illegal” arrivals. Another group of around 130 Jewish Tripolitanian children arrived in Syracuse in November 1948. From Syracuse, they were taken to hachsharot in Ostia and Nemi to prepare them for their eventual immigration to Israel. Before their arrival, Raffaele Cantoni, the president of the UCII wrote to the questore, or superintendent, of the region informing them of the arrival and departure of the children arriving from Tripolitania. Cantoni also wrote to the Direzione Generale della Pubblica Sicurezza to request their help with ensuring the safety of these children. In his letter, he also laid out the dangerous predicament of the Jews still in Libya faced and just how necessary it was for the Italian Jewish community and the Italian community-at-large to help them.32 Follow-up letters indicate many Italians from the mayor to the local carabinieri to the bishop of the region offered a “friendly welcome” to the Libyan refugees, which the Italian Jewish community said it would not forget.33

The late months of 1948 through 1949 show a hodgepodge effort by the IRO, the Jewish Agency, the JDC, the UCII, and the WJC to give housing, care, and maintenance to Libyan DPs at hachsharot and camps spread throughout the Rome and Naples regions, despite the unwillingness of the IRO to give the North African Jews formal refugee status. Josef Tajar, who had claimed to be from Bulgaria, was one of many sent to Genazzano, a town in the greater Rome metropolitan area where the JDC opened the Villa Clementi hachshara in the former hotel of local train engineer Antonio Clementi.34 The Genazzano hachshara opened in June 1948, as a replacement for the older Monte Mario II hachshara that subsequently closed down.35 It remained open until October 1949,36 and the care was, reportedly, above adequate for North African camps.37 In January 1949, a camp in Salerno was reconverted to house several hundred Libyan Jewish youth with the assistance of the Youth Aliyah; it was the only children’s center for Libyan youth operated by the IRO.38 Finally, in the third quarter of 1949, a camp was “especially established” for North Africans in Resina near Naples but “due to the large movements of North Africans into [Italy], it was found that facilities of the camp were not adequate,” and individuals were again moved to another camp.39 The final camp for Jewish Libyans was in Brindisi, which was viewed as an improvement to Resina.40 The atmosphere in the camps, however, was “one of extreme tenseness” as refugees felt uprooted and increasingly more insecure about their futures.41

For those wanting to leave but not yet in Italy, mid-1949 brought about the end to the exit/entry permit problem that had vexed their early immigration. As of April 5, 1949, Jews were allowed to exit freely without quotas, although they were only permitted to take £250 with them.42 Nearly all of the leadership groups connected to Jews in Libya and Italy agreed that Libyan Jews needed to stop coming to Italy illegally as a means to getting to Israel. They argued that Jews wanting to immigrate to Israel should go directly there from Libya, completely bypassing Italy as a stopover.43 Eventually, despite the financial holds and cost, this became the best option for many in Libya.

Yet, financial concerns and the continued fear of violence meant that Jews still could not easily and precipitously make aliyah. One exception to the view that Jews should bide their time in Libya while awaiting rights to immigrate to Israel was David Golding of the Youth Aliyah who argued as late as June 1949 that “Italy is by far a better place [than Tripoli] for a Hachshara for Tripolitanian youth.” In his letter to the JDC regarding their proposed creation of educational homes for Libyan Jewish children in Tripoli, Golding suggested a location change. He feared that within Libya “the state of security is subject to sudden changes…with new political developments the situation of free exit and freedom for Zionist activities may also change” and, therefore, as many children as possible should be taken out of Libya immediately.44 The Youth Aliyah had enough entry permits for Italy, and the JDC already had structures in place to help them in Italy. The JDC declined and decided to assist the Libyan Jewish community in Libya, helping them to make aliyah directly from Tripoli to Israel instead of via Italy.

From 1948 to 1951, nearly 30,000 Libyan Jews immigrated to Israel indicating that Libya no longer felt safe for Jews.45 Ultimately it would take the combined efforts of the Libyan, Italian, American, British, and Israeli Jewish communities to successfully transfer the great majority of the Libyan Jewish population to Israel. The journey still meant traveling through Italy as a means of escape for ten to fifteen percent of this community. Travel manifests attached to a 1951 report from the IRO to the International Tracing Service indicate that nearly all, if not all of the Libyan DPs had made it to Israel.46

37 JDC Archives, Records of the New York office of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee 1945-1954, Folder 625, “American Joint Distribution Committee,” November 23, 1949.

45 Maurice Roumani, “The Final Exodus of the Libyan Jews in 1967,” 77–100.