Sephardic Horizons In the context of Electronic Publishing1

By Judith Roumani2

Many thanks to Yitzchak Kerem for this opportunity and mazal tov, mazal bueno and felisitasiones to Sefarad ve Ha Mizrah for its thirty-year anniversary, a truly amazing record in the internet world, fulfilling a valuable service bringing us material that grows in quantity year by year.

I’d like to go back to about 2005, not quite 20 years, when I gave a paper on Sephardic periodicals of that time at a conference in Ladino held in Livorno. The proceedings of the conference were published in print in 2007 by the two-hundred-year old Sephardic press of Livorno, Belforte, which is still in existence and publishing Jewish books. I was privileged to meet Itzhak Navon there, who included me in the company of “lokitos,” the slightly crazy people, who study Ladino. Jean Carasso insisted that I present my paper in Ladino/Judeo-Spanish, and Alegra Amado was most helpful with the translation.

Only Yitzchak Kerem’s newsletter and

Ladinokomunita were online, as I remember, the rest were

paper publications. The Ladino press had been flourishing in Salonika

and in Istanbul and among immigrants to New York at the beginning of the

century. By the nineteen-forties it had declined and was moribund.3

In Europe, we had venerable academic journals published in Spain, the

UK, and France, that would sometimes address Sephardic Studies, and in

Argentina, Sefárdica, published by the CIDICSEF (Centro de

Investigación y Difusión de la Cultura Sefaradí). In France, we also had

the less formal La Lettre Sépharade, edited by Jean Carasso since

1991. The latter combined short articles, a large number of book and

music reviews in French, and proverbs, sayings and short stories in

Ladino/Judeo-Spanish. It later metamorphized into a publishing house, publishing

the important French-Judeo-Spanish dictionary by Isaac Nehama. In

Belgium, we had Los Muestros, founded in 1990 by Moise

Rahmani.

Only Yitzchak Kerem’s newsletter and

Ladinokomunita were online, as I remember, the rest were

paper publications. The Ladino press had been flourishing in Salonika

and in Istanbul and among immigrants to New York at the beginning of the

century. By the nineteen-forties it had declined and was moribund.3

In Europe, we had venerable academic journals published in Spain, the

UK, and France, that would sometimes address Sephardic Studies, and in

Argentina, Sefárdica, published by the CIDICSEF (Centro de

Investigación y Difusión de la Cultura Sefaradí). In France, we also had

the less formal La Lettre Sépharade, edited by Jean Carasso since

1991. The latter combined short articles, a large number of book and

music reviews in French, and proverbs, sayings and short stories in

Ladino/Judeo-Spanish. It later metamorphized into a publishing house, publishing

the important French-Judeo-Spanish dictionary by Isaac Nehama. In

Belgium, we had Los Muestros, founded in 1990 by Moise

Rahmani.

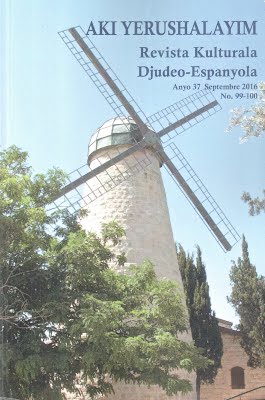

In Israel, there had been the weekly newspaper format

La Luz

de Israel, followed by

Aki Yerushalayim,

a journal

rather than a newspaper, in Turkey,

Şalom and its monthly

Ladino supplement,

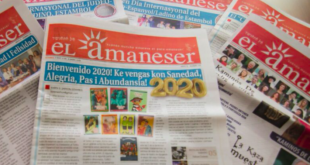

El Amaneser. In the USA, Erensia

sefardi appeared in several languages and the more informal

Ladino-language Ke Haber? in Florida. The English-language version

(together with Ladino/Judeo-Spanish) of La Lettre Sépharade

was published in a printed version, edited by Rosine Nussenblatt,

from the year 2000. It came out on a quarterly basis and consisted of

material translated from French, original reviews and articles in

English, and proverbs and stories in Ladino, until about 2007. And there

may be others that I have overlooked now.

In Israel, there had been the weekly newspaper format

La Luz

de Israel, followed by

Aki Yerushalayim,

a journal

rather than a newspaper, in Turkey,

Şalom and its monthly

Ladino supplement,

El Amaneser. In the USA, Erensia

sefardi appeared in several languages and the more informal

Ladino-language Ke Haber? in Florida. The English-language version

(together with Ladino/Judeo-Spanish) of La Lettre Sépharade

was published in a printed version, edited by Rosine Nussenblatt,

from the year 2000. It came out on a quarterly basis and consisted of

material translated from French, original reviews and articles in

English, and proverbs and stories in Ladino, until about 2007. And there

may be others that I have overlooked now.

Today, one of the few publications

that have survived on paper that I can think of is

El Amaneser,

which is also online. The paper issues of those journals and newsletters

from previous decades, so rich in Sephardic history, genealogy,

language, and folklore, are quite rare, and deserve to be preserved.

Yeshiva University’s Sephardic Studies program published a print

journal, The American Sephardi for many years.

Aki

Yerushalayim, originally edited by Moshe Shaul,

has been particularly influential in setting the parameters of the

language, standardizing spelling, and influencing researchers and

writers around the world. Its printed version has transformed into an

online, more occasional, and very elegant format that privileges

creative writing in Ladino, but the original journal has probably been

the inspiration for the new Akademia de Ladino established by the Israel

and Spanish governments.

Today, one of the few publications

that have survived on paper that I can think of is

El Amaneser,

which is also online. The paper issues of those journals and newsletters

from previous decades, so rich in Sephardic history, genealogy,

language, and folklore, are quite rare, and deserve to be preserved.

Yeshiva University’s Sephardic Studies program published a print

journal, The American Sephardi for many years.

Aki

Yerushalayim, originally edited by Moshe Shaul,

has been particularly influential in setting the parameters of the

language, standardizing spelling, and influencing researchers and

writers around the world. Its printed version has transformed into an

online, more occasional, and very elegant format that privileges

creative writing in Ladino, but the original journal has probably been

the inspiration for the new Akademia de Ladino established by the Israel

and Spanish governments.

In this changing publishing climate, we founded Sephardic Horizons in 2009. We are officially registered with an ISSN international serial number, and we are a project of a Jewish studies institute, the Jewish Institute of Pitigliano, allowing us to receive tax-deductible donations for our working expenses. From the beginning, Sephardic Horizons was purely online, and this has enabled us to keep our expenses low. Anyone, in any country, can print out our articles for themselves, if they wish. In September 2009, I had broken my knee and my entire leg was immobilized in a cast, so that gave me some time to think. The idea actually came to me at a vijita de Alhad of the Washington DC area. Our vijitas are a fairly close-knit group, originally founded by the late Flory Jagoda, and the deliciousness of the food and the music make up for any errors in Ladino. The vijitadores seemed to approve of the idea of a journal, and over the years since then, several have been loyal repeat contributors and supporters, to all of whom we are very grateful.

Sephardic Horizons tries to appeal to both academics and non-academics who, incidentally, in the Sephardic community can be very knowledgeable. We have an editorial board and an advisory board, an editor (I), an associate editor (Dr. Annette B. Fromm), and a webmaster (Altan Gabbay). Both of the latter go beyond the call of duty. Article submissions are sent to readers who are qualified in the particular field, and we are not sparing with editors’ comments, suggestions, and criticism. Some authors might seem to feel slightly offended when their article is not accepted as perfect when submitted, but I, as an author or editor, feel that nothing is perfect the first time, and personally that another critical eye on my work can only benefit me. For Ladino/Judeo-Spanish articles, we mostly edit very lightly, if at all. We publish many book reviews, and occasionally reviews of performances or exhibits, and these, as long as they make sense and show that the reviewer knows the field, receive minimal editing because reviewers ought to be able to express their views freely.

Some highlights from our publications over eleven volumes: an original essay by the Israeli novelist AB Yehoshua, and an exclusive interview; a series of three articles on uses of Judeo-Arabic by the professor and writer Sasson Somekh, of Iraqi origin; unpublished prose, poetry, and portions of a diary provided by the Tunisian-Jewish writer Albert Memmi; articles by Liliana Benveniste of Argentina, Rachel Amado Bortnick, founder of Ladinokomunita, Haim Vidal Sephiha, the father of Judeo-Spanish studies in France, Jean Carasso, founder of the French original of La Lettre Sépharade, interviews and articles by Rosine Nussenblatt, editor of its English version, several reviews and genealogical articles by Ralph Tarica, poetry by Matilda Koen Sarano (Israeli author of manuals for learning Ladino), an upcoming review by Steven Bowman of a book on Jews on Salonika, etc. We have also reviewed, over the last eleven volumes, most of the important works in the field. We have published, about five years ago when the subject was new to all, the first critique of the Spanish citizenship application process, written by Dogan Akman, a Canadian jurist and judge; an original play in Ladino by Jane Mushabac; and special issues on Tunisian Jewish novelists, Greek Jewish history, Italian Jewry, Albert Memmi, Jews of Libya, and several literature-themed issues such as “Sephardim and the City,” and “The Risks that Sephardic Novelists Take,” based on special sessions held at meetings of the American Association for Jewish Studies. The coordinating needed for these special issues is far from easy, so we don’t do them very often. I find that “clusters” of items on a particular topic which sometimes occurs naturally are much more efficient and do not force some authors to wait for a long time to see their work published. Interestingly, when there are special issues on particular topics, they often provoke further material on similar topics, so there is a sort of conversation going on between scholars.

You will understand by now that Sephardic Horizons' definition of “Who are the Sephardim?” is very broad, what some people prefer to call “Sephardi-Mizrahi.” I personally, as described in more detail on our website, prefer the broader definition. I follow the views of Daniel Elazar, who in his book The Other Jews refers to the common origins in Babylonian Nusach, Halakhah, and Minhag before the Iberian “interlude.” Thus, I do not have a great problem with including Arabic-speaking Jews under the rubric of Sephardim. A number of scholars would support this approach.

Online publishing of scholarly

articles is receiving more and more acceptance and has been for more

than a decade. In the less scholarly but important area of language,

Ladinokomunita and other informal online outlets such as

Sefaradimuestro

of Sharope Blanco,

La Boz Sefaradi (The

Sephardic Voice) of the

Sephardic Jewish Brotherhood of America,

La

Ermandad Sefaradi, published weekly, and containing much original

material in Ladino, such as stories of Djoha, the American Sephardi

Federation’s weekly and monthly publications,

El Diario Judio in

Mexico, which I understand publishes partly in Ladino (Judeo-Espanyol),

and has a section called Rincón Sefaradí, are all very valuable. In

Argentina, Liliana Benveniste’s continuing online publication

eSefarad

is published weekly, while she animates musical events and vijitas

that include performers and speakers around the world. Some of the above

online publications reproduce material published elsewhere, rather than

original writings, as

Sephardic Horizons strives to do.

Another original serial

Ladino 21, consisting of interviews in Ladino, posted

online regularly by Carlos Yebra López, constitutes an excellent use of

the internet. We must mention and honor the continuing airing in Spain

of Radio Sefarad, organized and performed by Matilde Gini

de Barnatán and her daughter, Rajel. The organization

Vidas Largas in

France also has bi-weekly hour-long weekly radio broadcasts entitled

Camino Séfarad, on every other Thursday.

Online publishing of scholarly

articles is receiving more and more acceptance and has been for more

than a decade. In the less scholarly but important area of language,

Ladinokomunita and other informal online outlets such as

Sefaradimuestro

of Sharope Blanco,

La Boz Sefaradi (The

Sephardic Voice) of the

Sephardic Jewish Brotherhood of America,

La

Ermandad Sefaradi, published weekly, and containing much original

material in Ladino, such as stories of Djoha, the American Sephardi

Federation’s weekly and monthly publications,

El Diario Judio in

Mexico, which I understand publishes partly in Ladino (Judeo-Espanyol),

and has a section called Rincón Sefaradí, are all very valuable. In

Argentina, Liliana Benveniste’s continuing online publication

eSefarad

is published weekly, while she animates musical events and vijitas

that include performers and speakers around the world. Some of the above

online publications reproduce material published elsewhere, rather than

original writings, as

Sephardic Horizons strives to do.

Another original serial

Ladino 21, consisting of interviews in Ladino, posted

online regularly by Carlos Yebra López, constitutes an excellent use of

the internet. We must mention and honor the continuing airing in Spain

of Radio Sefarad, organized and performed by Matilde Gini

de Barnatán and her daughter, Rajel. The organization

Vidas Largas in

France also has bi-weekly hour-long weekly radio broadcasts entitled

Camino Séfarad, on every other Thursday.

In terms of print publications, I see that the organization La Ermandad Sefaradi has a new quarterly periodical entitled The Sephardic Brother, in English with an article in Ladino, and the American Sephardi Federation continues with its print publication, The Sephardi Report, as well as its other online publications and multiple programs in Sephardic culture and creativity. We should also acknowledge HaLapid, the beautiful, glossy publication of the Society for Crypto-Judaic Studies now in its thirtieth year.

Sephardic Horizons tries to bridge these various genres, to appeal to academics and non-academics. I hope we are successful. We have over a thousand, about fourteen hundred readers, no advertising, almost all original writing, and you may sign up for priority online delivery, totally free, three times a year, by going to our website, https://www.sephardichorizons.org, or of course by googling us.

I’ll conclude here, thanks for listening, and if there are any questions or items you would like me to discuss, please write in the chat. Many thanks, mersi muncho, to Yitzchak Kerem and to all listeners!

1 This paper was delivered in the context of the zoom conference in celebration of the thirtieth anniversary of Sefarad ve HaMizrah, July 28, 2021. A selection of the presentations from the zoom conference can be followed on the Sefarad vehamizrah YouTube channel.

2 Judith Roumani is the founder and editor of Sephardic Horizons, and director of the Jewish Institute of Pitigliano. She holds a doctorate in Comparative Literature from Rutgers University, and has published a monograph on Albert Memmi and numerous articles, chapters and reviews on Sephardic literature. She is the author of Jews in Southern Tuscany during the Holocaust: Ambiguous Refuge (Lanham, Md: Lexington Books, 2021) and has translated or edited three books on North African Jewish culture. Another book is in the works.

3 Synagogues had their bulletins, all in English, and that was about it. Publications from the Seattle community such as the Congregation Ezra Besaroth Bulletin and their monthly The Clarion (issues from the 1940s) may be found in the digital archives of the University of Washington. Devin Naar discusses the earlier flourishing of the Ladino press in New York, in “Between ‘New Greece’ and the ‘New World’: Salonikan Jewish Immigration to America,” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora (2009), read as PDF on Academia.org.