Solomon de Oliveyra:

A Seventeenth Century Sephardic Sage

by Marvin J. Heller1

Ayyelet head-piece

Among the Sephardic sages of Amsterdam is R. Solomon de Oliveyra (1633-1708), a multi-faceted person of prominence in his time but, like so many sages over the ages, not well remembered today outside of academic sources.2 Solomon de Oliveyra, a rabbi (hakham) and teacher in the Talmud Torah Etz Haim of the Keter Torah association of the Amsterdam Portuguese community, of which he later became president, was a member of the rabbinical council, over which he presided after the death of R. Jacob Sasportas (c. 1610-98). In addition to these rabbinic positions, Oliveyra worked as a corrector in the printing-house of Uri Phoebus.3 He was the author of a number of varied multi-lingual works on grammar, lexicography, other philological subjects, poetry, and riddles. Several of these subjects related to the Torah and Talmud. Albert Van Der Heide has described Oliveyra as “the preeminent and omnipresent Hebrew poet of Jewish Amsterdam.”4

Solomon de Oliveyra (Oliveira, 1633-1708) was the son of R. David Israel de Oliveyra, also a Portuguese scholar. Solomon de Oliveyra’s place of birth, whether Lisbon or Amsterdam, is uncertain. Albert Van Der Heide suggests, however, that as Oliveyra’s parents were fugitive conversos, as documented in Amsterdam in 1628, he must have been born in the latter location. Also, based on the marriage certificate issued by the city of Amsterdam, Oliveyra married Rached Dias in 1660, when twenty-seven years old, again attesting to Amsterdam as his place of birth.5 Although a scholar, professor, and poet, as well as serving as a hakham of the Sephardic congregation of Amsterdam, Oliveyra became an adherent of Shabbetai Zevi; he composed liturgical verse in his behalf.

An important part of Oliveyra’s prolific output was poetry, written in a classical Hispanic-Arabic style of the Middle Ages. Cognizant of his audience, however, Oliveyra also adopted contemporary conventions of stanza and rhyme. Van Der Heide finds that, compared to the Hebrew poems of the “plain and predictable material written by the Hebrew poets of the seventeenth century,” Oliveyra’s poetry was to be “neither futile nor meaningless.” Nevertheless, he does not feel that it was on the same level as that of Oliveyra’s Italian contemporaries.6 Another area in which Oliveyra made a considerable contribution was his lexicographic works, addressing the needs of a converso returning to rabbinic Judaism and its literature, not an easy undertaking.

The Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book attributes fourteen titles to Oliveyra, but those are works in Hebrew letters or bilingual, such as the Hebrew-Portuguese Etz Hayyim, but not including works in other scripts nor other Hebrew titles that Oliveyra worked on or contributed to, such as the Tikkun Kriah le-Yom ve-Lilah, but of which he was not the primary author.7 Among the non-Hebrew works were a Portuguese translation of the Canon of Avicenna (1630), and “Calendario Fazil y Curioso de las Tablas Lunares (with the text of the Pentateuch, 1666, 1726) with Circulo de los Tequphot (1687); Enseña á Pecadores Que Contiene Diferentes Obras Mediante las Quales Pide el Hombre Piedad á Su Criador (1666), a Portuguese translation of part of Isaiah Hurwitz’s ascetic work; some occasional speeches in Portuguese.” These latter works are not addressed in this article.8 Herein, several of Oliveyra’s titles are described in some detail; others are noted briefly, giving the reader an appreciation of this sage’s oeuvre.9

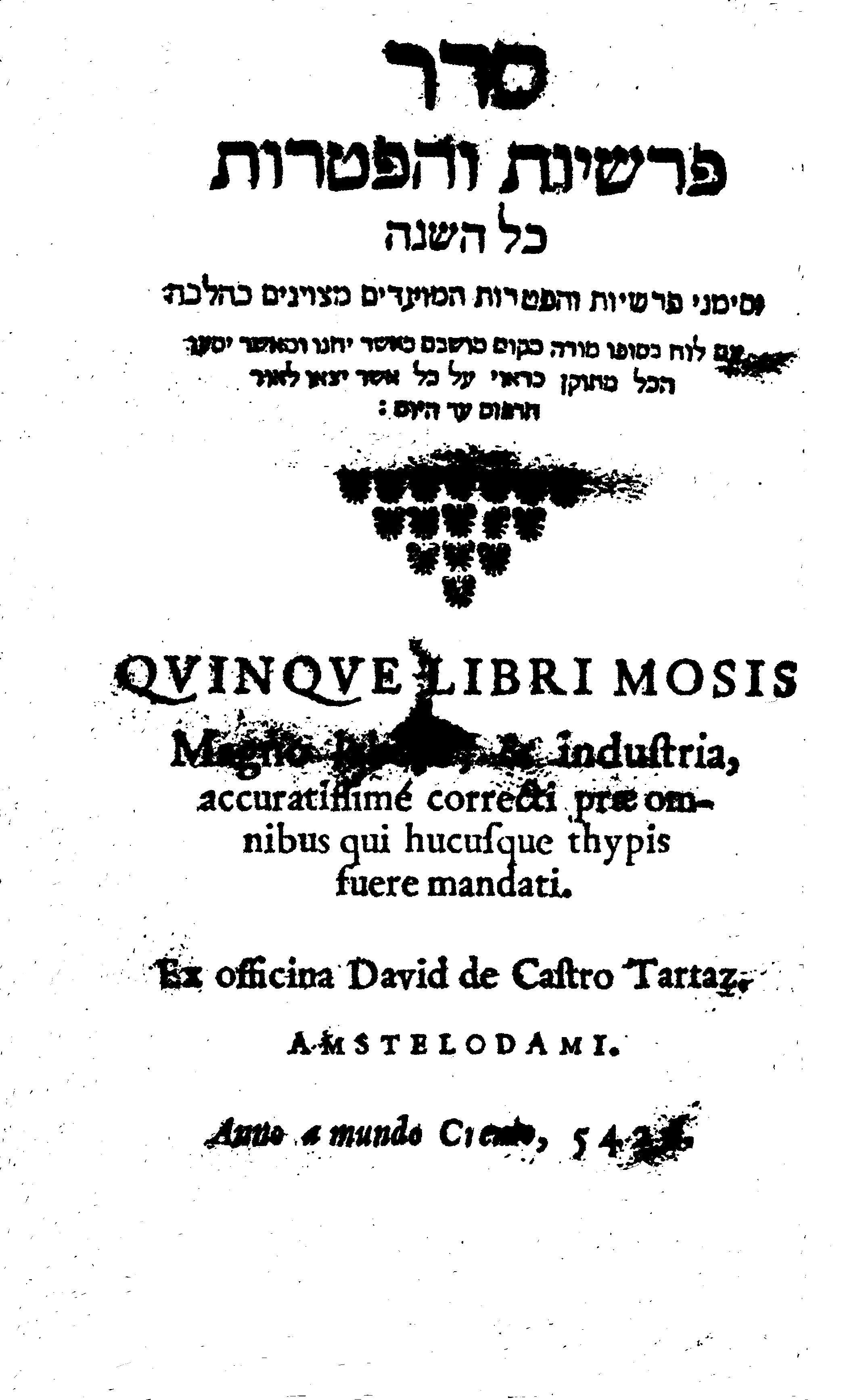

The primary publisher of Oliveyra’ books was David de Castro Tartas (c. 1625–c. 1700), active from 1662 to 1698 in Amsterdam. Their relationship began in 1665, when Ayyelet Ahavim and Sharshot Gablut were printed, continuing through 1688 when Tartas issued Livro da Gramatica Hebrayca & Chaldayca. Tartas published almost seventy books in Hebrew and a number in other languages, primarily Spanish. Nevertheless, Tartas was not among Amsterdam’s major publishers of Hebrew books; other leading printers of such works included Uri Phoebus ha-Levi and Joseph Athias. Fuks and R. G. Fuks-Mansfeld (hereafter Fuks) describe Tartas as being “on the fringes of Hebrew book-printing in Amsterdam.” He did excel, however, in another field, publishing Spanish and Italian language newspapers.

Tartas was the son of conversos who came to Amsterdam in 1640 via France where they resided in the city Tartas (Gascogne). In Amsterdam, they returned to their ancestral faith, taking the name Tartas. David’s brother, Isaac, had gone to Recife and Bahia where, refusing to abjure his faith, he was burned at an auto-da-fé in 1647.10 David Tartas learned the printer’s craft at the press of Menasseh Ben Israel, working there as a compositor. In 1662, he established his own press. According to Friedberg, Tartas initially worked alone but, being successful, added workers so that he eventually had a large staff.11 His output was varied and, in some cases notable. He printed prayer-books, discourses, a Mishnah, and numerous other titles, primarily small works, in addition to newspapers. Among the books published by Tartas, as noted above, are several by Oliveyra. A small number of books that Oliveyra worked on were also published by Uri Phoebus, noted below.

We have briefly reviewed Oliveyra’s background and the Tartas press, where the majority of Oliveyra’s books were published. In the core of the article, we will describe the various books that he wrote, several in some detail, and, to a lesser degree, other works that he was involved with, such as giving approbations and concerning Shabbetai Zevi.

I

Ayyelet Ahavim:

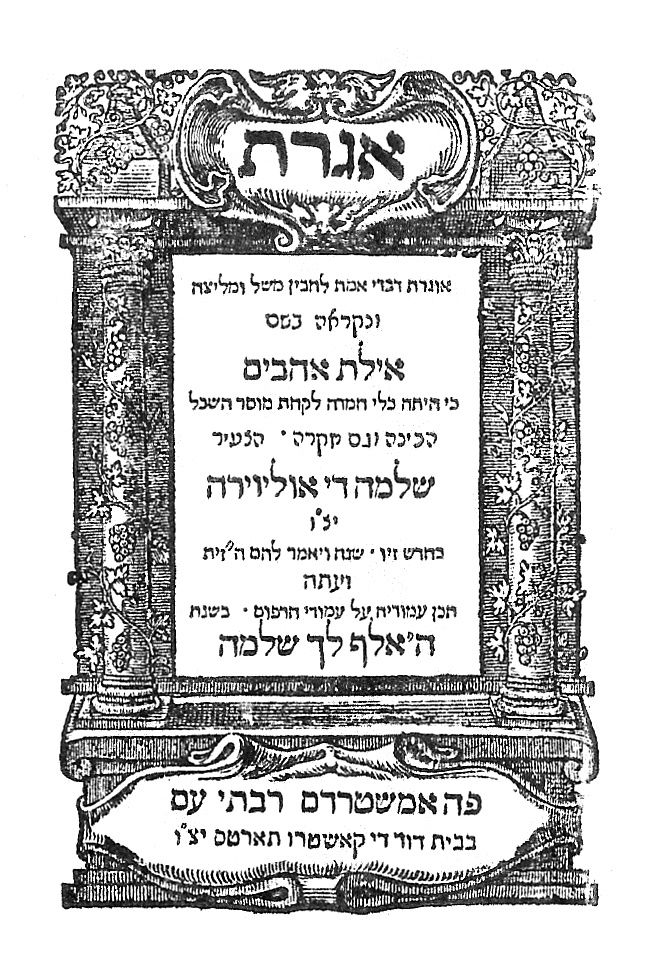

Our first Oliveyra title is Ayyelet Ahavim, a rhetorical and poetic treatise on the Akedah (sacrifice of Isaac). Ayyelet Ahavim is Oliveyra’s magnum opus, written in prose and poetry. Its title is from “A loving hind (ayyelet ahavim) inspiring favor” (Proverbs 5:19). It was published in 1665 by Tartas in a small sextodecimo format (160: 32, [2] ff.).12 The title-page is embellished with a pillared frame and a header that informs that it is a letter אגרת, stating:

Igeret

A compilation אגרת of words of truth “To understand a proverb, and a figure” (Proverbs 1:6).

It is entitled

Ayyelet Ahavim

for it was “a precious vessel” (Hosea 13:15, Nahum 2:10, II Chronicles 32:27),

“To receive the instruction of wisdom” (Proverbs 1:3).

“He established it and searched

it out” (Job 28:27), the youth

Solomon de Oliveyra

in the month of Ziv, in the year “But the olive tree (662 = 422) הזית said to them” (Judges 9:9).

And now brought to press, in the year

“O Solomon, must have one thousand

(ה"אלך לך שלמה (5425 = 1665” (Song of Songs 8:12).

Here, Amsterdam “the city great with people” (Lamentations 1:1).

At the press of David de Castro Tartas

Oliveyra’s introduction follows (2a-b) in which he states that he does not wish to delve into deep explanations nor to go up to the heights of discourse, but rather his heart wishes to speak of the greatness of that “righteous man, who quarried the fetters of love, of that which he formed יצורו for the love of the One Who formed him יוצרו.” Oliveyra’s intent is to investigate this holy and wondrous deed. Among the several reasons that he entitled this work Ayyelet Ahavim is that it is on the love of Abraham and his soul for God “As the hart longs for water streams” (cf. Psalms 42:2).

1665, Ayyelet Ahavim

Courtesy of Virtual Judaica

The wide-ranging text, composed of interspersed prose in a single column in square letters and verse in a larger vocalized font, is comprised of numerous aggadot, and including riddles and parables. In one section the alternating paragraphs of verse are between father and son. The prose text is accompanied by infrequent marginal references.

Albert Van Der Heide describes Ayyelet Ahavim as relating the story of the Akedah:

In full rabbinic attire: it includes references to all the aggadic embellishments to be found in midrashic literature on the subject. In addition, it contains two novelistic digressions, namely the story of Abraham’s youth and his burgeoning belief in the one God, based on the aggadah, and Ishmael’s ‘Rake’s Progress’, his unruly life in the desert, his marriage to Fatima and his return to Abraham’s tent. . . . the little book is written in prose melitsa, in flowery, highly styled rhyming prose, interspersed with metrical poems. It makes pleasant reading and reveals a sound knowledge of the Hebrew language and rabbinic literature.13

The volume concludes with a star-form pictograph, a prayer in prose, the

animal-like tailpiece employed by Tartas in several of his publications,

and a postscript (epilogue) by Oliveyra, which ends that he has placed

this book before those who see (understand) it, to seek associates, to

hear their voice, and they will say concerning it, before the eyes of

all who look into it:

The volume concludes with a star-form pictograph, a prayer in prose, the

animal-like tailpiece employed by Tartas in several of his publications,

and a postscript (epilogue) by Oliveyra, which ends that he has placed

this book before those who see (understand) it, to seek associates, to

hear their voice, and they will say concerning it, before the eyes of

all who look into it:

“You have the thousands O Solomon”

(Song of Songs 8:12)

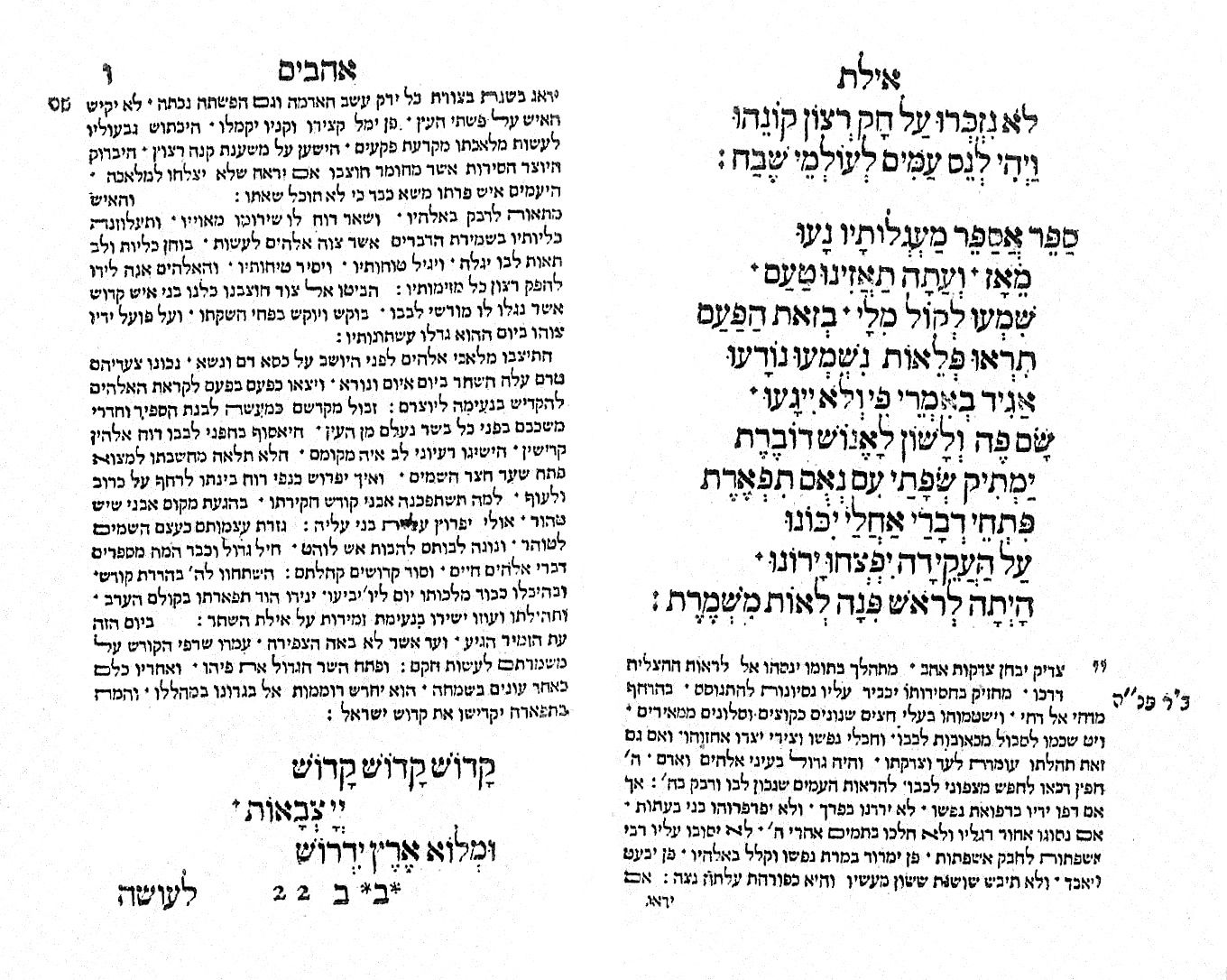

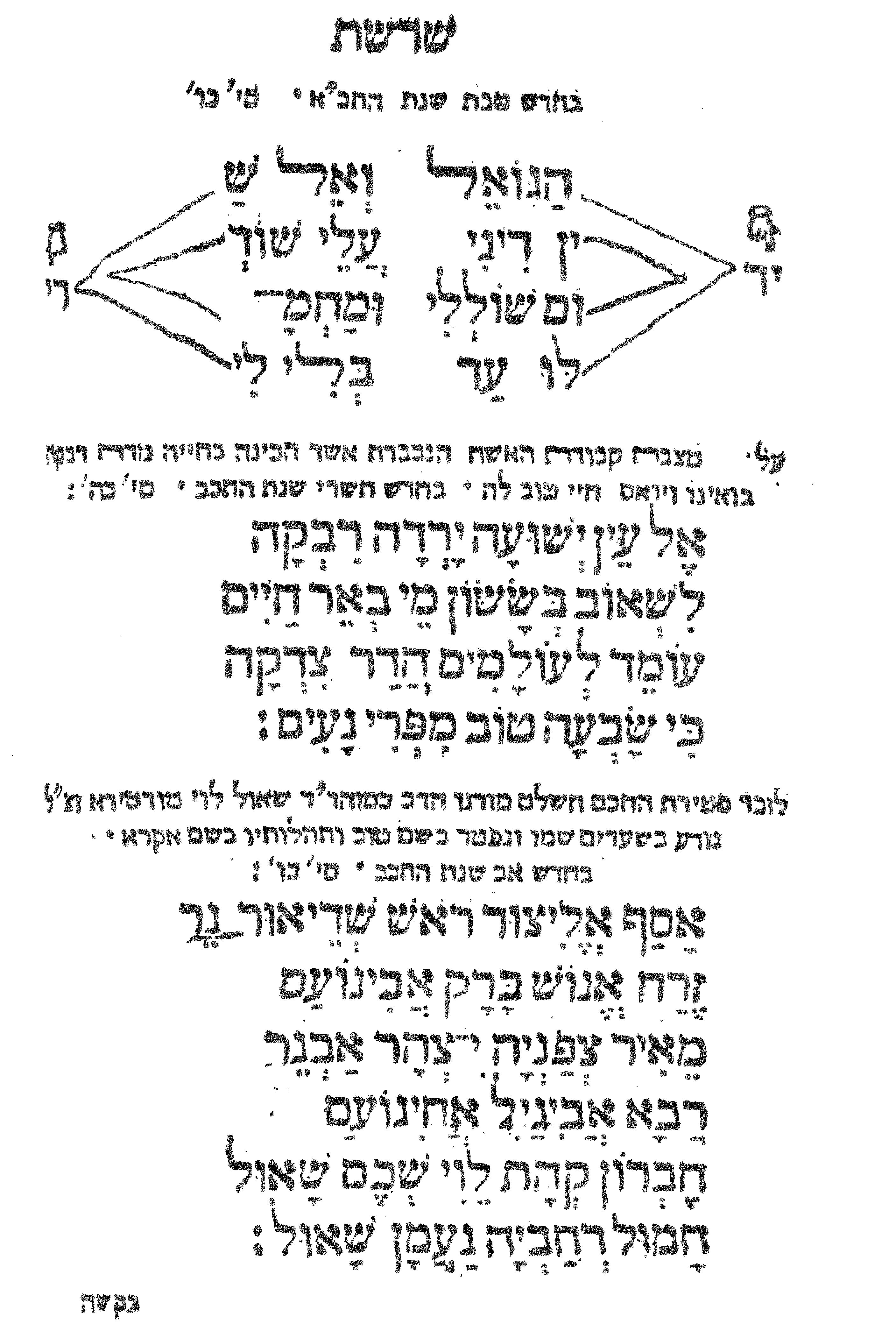

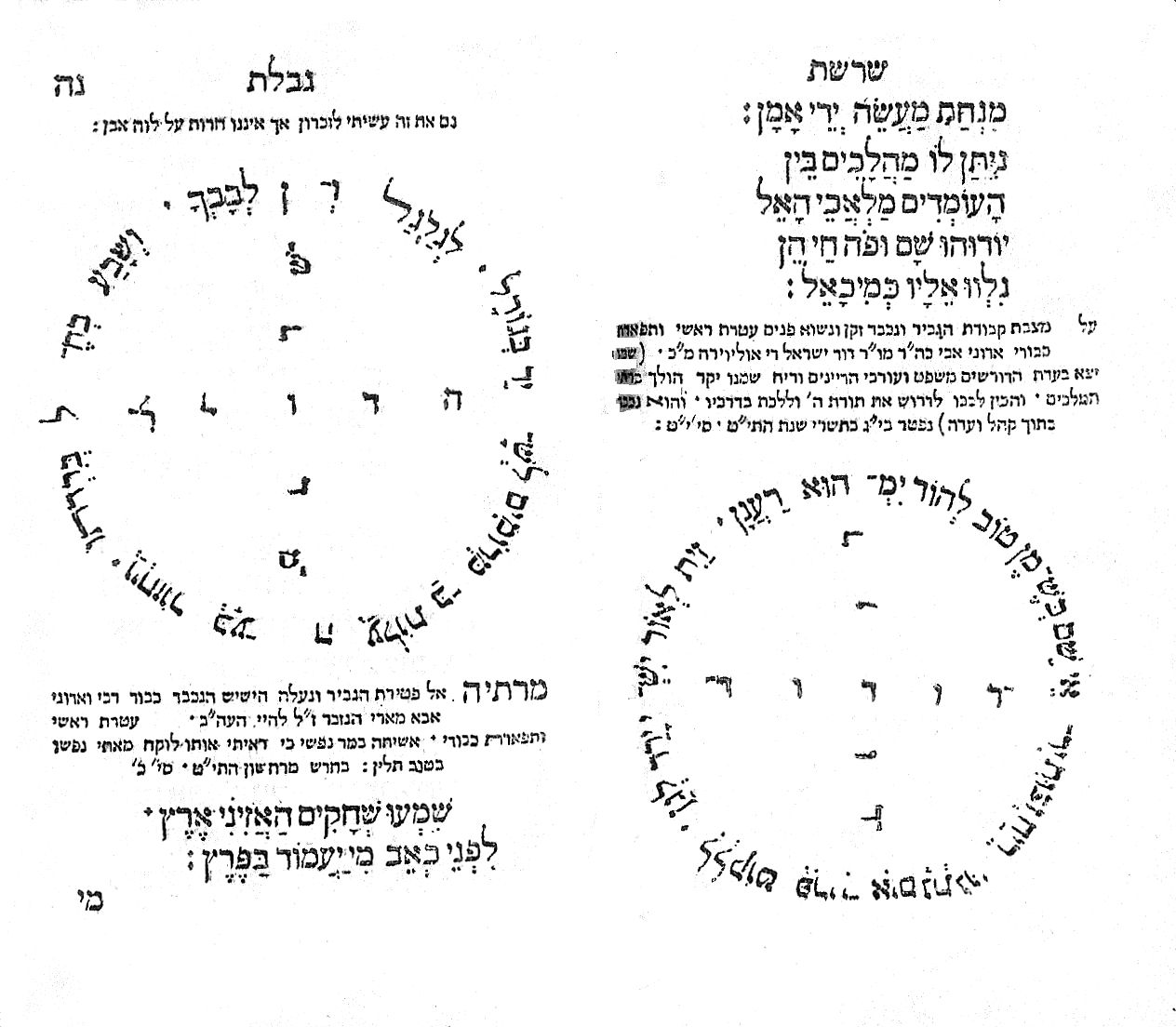

Sharshot Gablut:

This is a Hebrew rhyming lexicon and treatise on poetry published by David de Castro Tartas in 1665 in a small sextodecimo format (160: 70, [2] ff.). The title is from “And on the breastplate you shall make chains at the edge (sharshot gablut), twisted like cords, of pure gold” (Exodus 28:22). The title page has the same frame as Oliveyra’s Ayyelet Ahavim, and was also printed in 1665.

The title-page states that it is:

Sharshot Gablut,

“He set the bounds” (Deuteronomy 32:8) of rhymes of the roots comparable “one to the other” (Genesis 37:19, et. al).

“And its hand took hold of the heel” (cf. Genesis 25:26) of its neighbor as the chain work “that every man should rule”

(Esther 1:22).

With the rules of “measures of length, of meter” (cf. Leviticus 19:35),

in the service of verse with its history,

to be “an ornament of grace” (Proverbs 1:9, 4:9) for the poet, “with cords of love” (Hosea 11:4)ת

a work of verse.

Solomon de Oliveyra

Beginning of the work was on Rosh Hodesh Tammuz, “I have come באתי

(413 = Thursday, June 26, 1653) into my garden” (Song of Songs 5:1).

Printed in the year O Solomon, must have one thousand (ה"אלף לך שלמה (5425 = 1665”

(Song of Songs 8:12).

At the press of David de Castro Tartas

Oliveyra’s introduction follows (2a-b) in which he notes that verse is precious in the eyes of God and man, the ladder of the levels of verse standing on the ground in the holiness of the house of God and reaching to heaven. He references the great antiquity and history of verse, beginning with Moses, Deborah, David, and Solomon, and the rules of composition.

The text is comprised of pages of rhymes in alphabetic order, a discourse on Hebrew poetry, examples of Hebrew poetry from biblical times, as well as several of Oliveyra’s poems, and explanations for the use of diagrams. Fuks describes Sharshot Gablut as “a lexicon and handbook of Hebrew rhyme” and as “a treatise on Hebrew poetry; . . . examples of Hebrew poetry from biblical times until the 17th century.”14

1665,

Sharshot Gablut

Courtesy of Virtual Judaica

Among the contents is a eulogy for Isaac de Castro Tartas who, as noted above, was a converso, born in Portugal and resident in Amsterdam. At the age of sixteen, in 1644, Isaac traveled to Recife in Dutch Brazil, where there was a Jewish community. From there Isaac went to Bahia in Portuguese Brazil, reputedly to convert New Christian relatives, or perchance to avoid Dutch justice for his commercial activities. Although he claimed to be an unbaptized Jew, evidence to the contrary was produced and Isaac was extradited to Portugal where he admitted that he was an observant Jew and burned at an auto-da-fé in Lisbon in 1647.15 Oliveyra memorialized Isaac de Castro’s martyrdom in verse in Sharshot Gablut, with an introductory paragraph that begins “On the demise of the youthful, comely, and God-fearing man, Isaac de Castro Tartas, stately as the cedar, whose life flames of fire did devour [because of his zeal] for the unity and holiness of God. His pure soul left [the body] in innocence. Well may he be called a martyr.” A portion of the eulogy states:

They swallowed alive the lamb at

whom they hissed

And changed to night his day

They darkened and profaned his

holiness [piety].

Go worship the cross! said they

[the Inquisition],

[As they] smoothing their

deceitful tongue [ready] to swallow him,

[Not knowing, like dumb cattle,

their folly,

The work of the hands of man -

wood and stone.]

And he answered in a pleasant

tone and with joyful heart,

Wherefore do ye annoy and confuse

me?

I shall rise and be strengthened,

I triumph

[Whilst] you crouch and fall to

naught.16

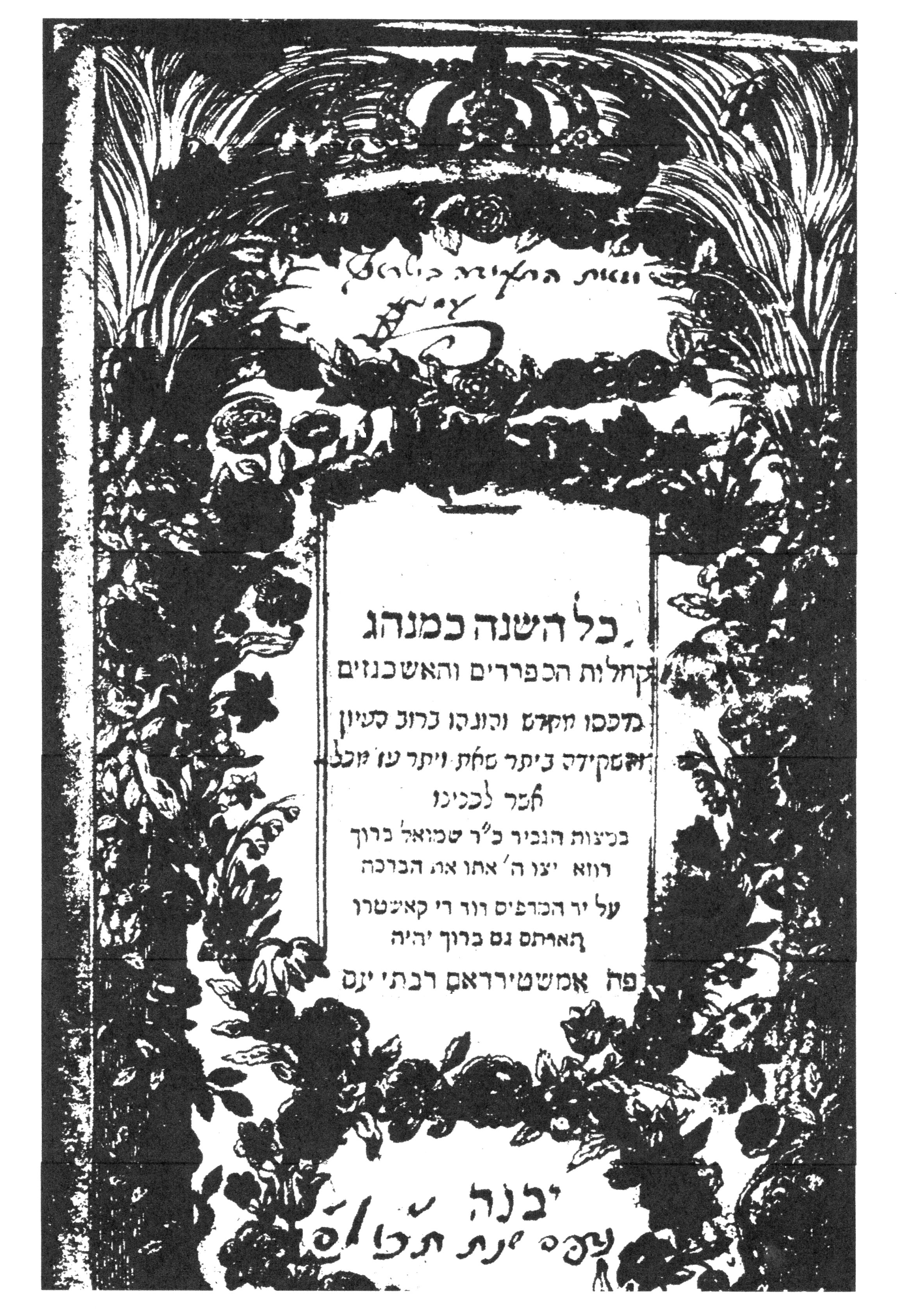

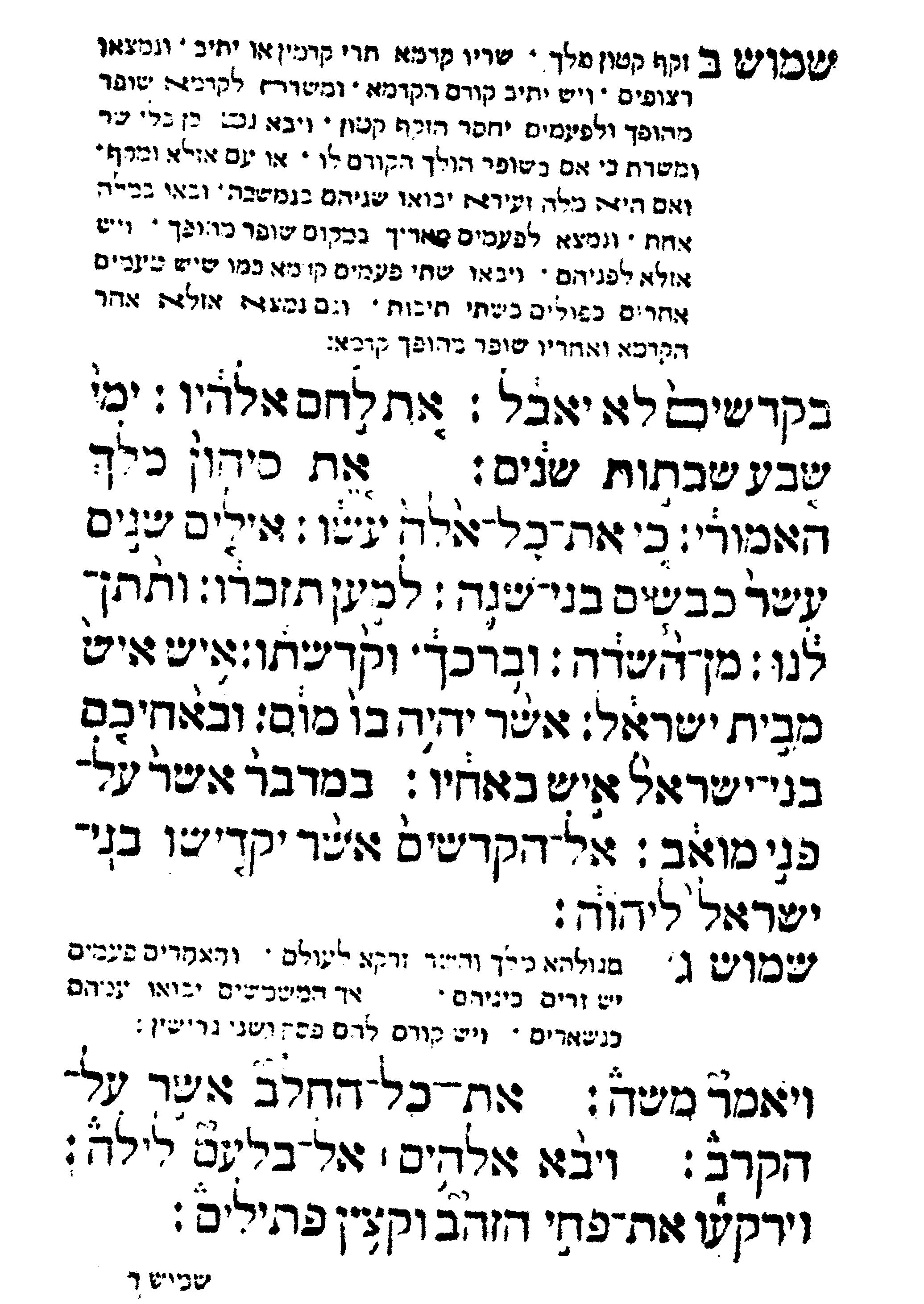

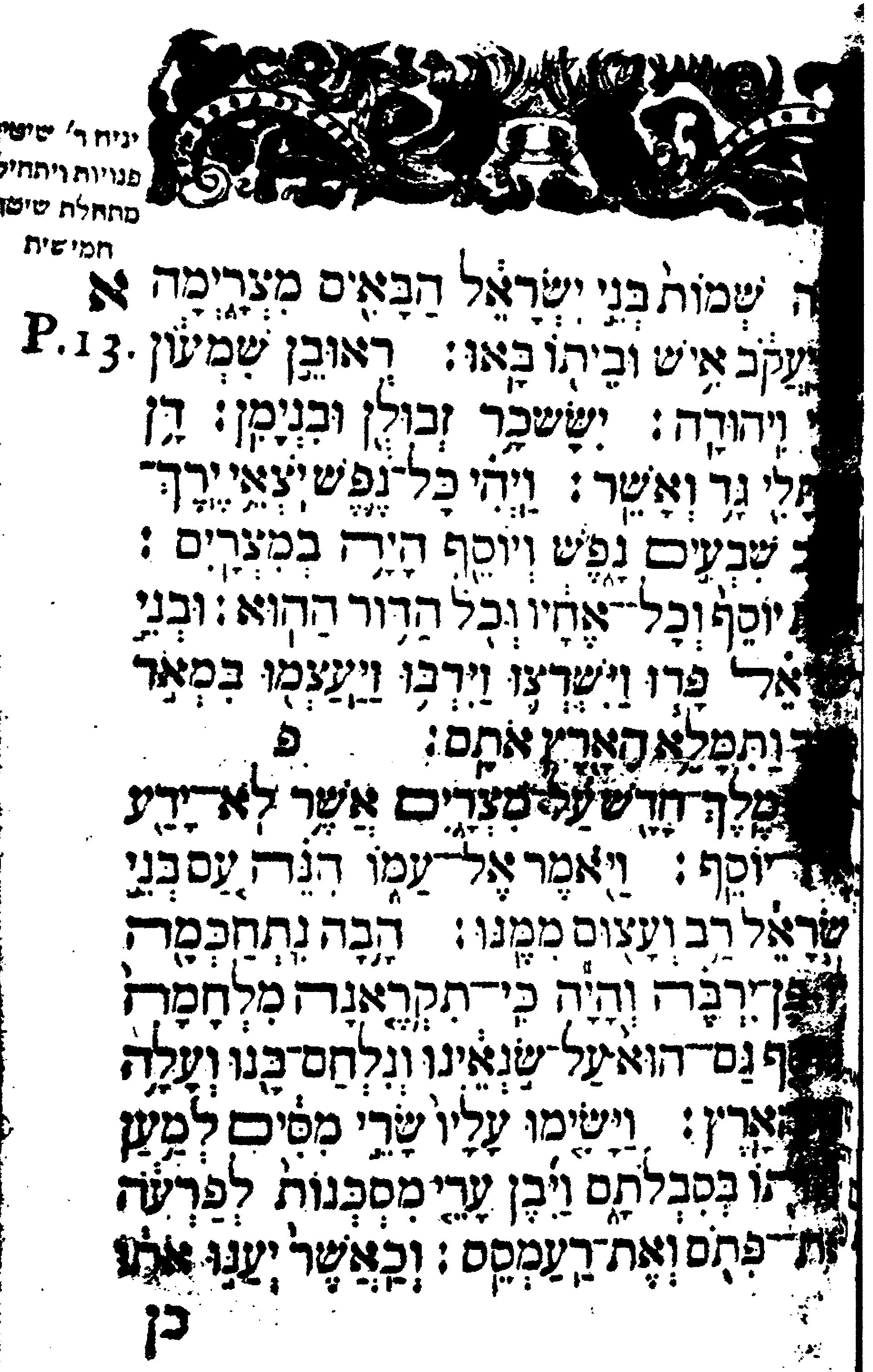

Hamishah Homshei Torah with Tikkun Soferim:

Another linguistic work, that is language-oriented, is Hamishah Homshei Torah with Tikkun Soferim, on the correct writing of biblical texts for sofrim (scribes). This was printed at the Tartas press in 1666, in a small format, this a duodecimo (12:0, [xii], 1-325, [326-328], 329-446, [447-450] pp.). Tikkun Sofrim (tiqqūnēi sōferīm) to the correct writing and, here, printing of books of the Bible, that is with the tagim (crowns) and ritual script of Hebrew letters. The copper plate title-page states that it is for the entire year according to the customs of the Sephardic and Ashkenazic communities and that it was financed by R. Samuel ben Isaac Baruch Rosa. Fuks informs that there are “several different copies extant. Several have an engraved title with a full Heb. text. . . . without the printed title and without the calendar at the end. There also exist copies with the same engraved titlep. (sic.) but with a slightly different Heb. Text.”17 The only copy seen by this writer is the one reproduced below.

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

The title-page is followed by the introduction remarks with the heading “Our help is the name of the Lord, maker of heaven and earth” (Psalms 124:8). Next is a page of verse with the tailpiece below it and then Oliveyra’s introduction which begins,

The Lord, God, spoke to us and gave us His Torah by Moses, His prophet, who wrote the Sefer Torah with Hebrew letters. Our eyes can see, it was without nekudot (vowels) or te’amim (diacritical) marks. In truth, it was made known to the children of Israel how to read, chant, and sing them orally.

Oliveyra continues that what was made known did not include the instructive forms of the cantillation and continues to address that subject in the body of the introduction, concluding with verse by Oliveyra and a brief statement by R. Elijah ben Michael Judah Leon, the corrector, who dates the beginning of the work to Sunday, 4 Tishrei, (September 3, 1665) in the year “Indeed, You loved the people greatly, all its holy ones were in your hands, for they תכו planted themselves at Your feet bearing [the yoke] of Your utterances (426 = 1666)” (Deuteronomy 33:3).18 Next is an approbation from R. Isaac Aboab and R. Moses Raphael of Aguilar, who inform that the text was corrected by students of the Amsterdam academy, and another approbation from R. Joseph d Fano, R. Emanuel Abenatar, R. Joshua de Silva, R. Samuel Pinto, R. Abraham Senior Coronel, and R. Elijah de Leon who attest to the accuracy of the text.

A second more detailed bilingual title page follows and then the text of Hamishah Homshei Torah with full cantillation. That section concludes that it was completed on Friday 16 Shevat (January 12) “Now heed My voice, I shall advise you, may God be with you היה אתה. You be a representative to God, and you convey the matters to God (426 = 1666)” (Exodus 18:19), informing that Tikkun Sofrim was prepared in a little more than four months, that is, from the beginning of September to early January.

Next are pages with the blessings to be recited before and after reading the Haftarot for Shabbat and then for festivals, Rosh Ha-Shanah and for Yom ha-Kippurim, and then the Haftarot. The volume concludes with a listing of the Haftorat to be read by occasion, and then a calendar calculating when occasions occur. Hamishah Homshei Torah with Tikkun Soferim is an attractive, practical, and highly functional volume

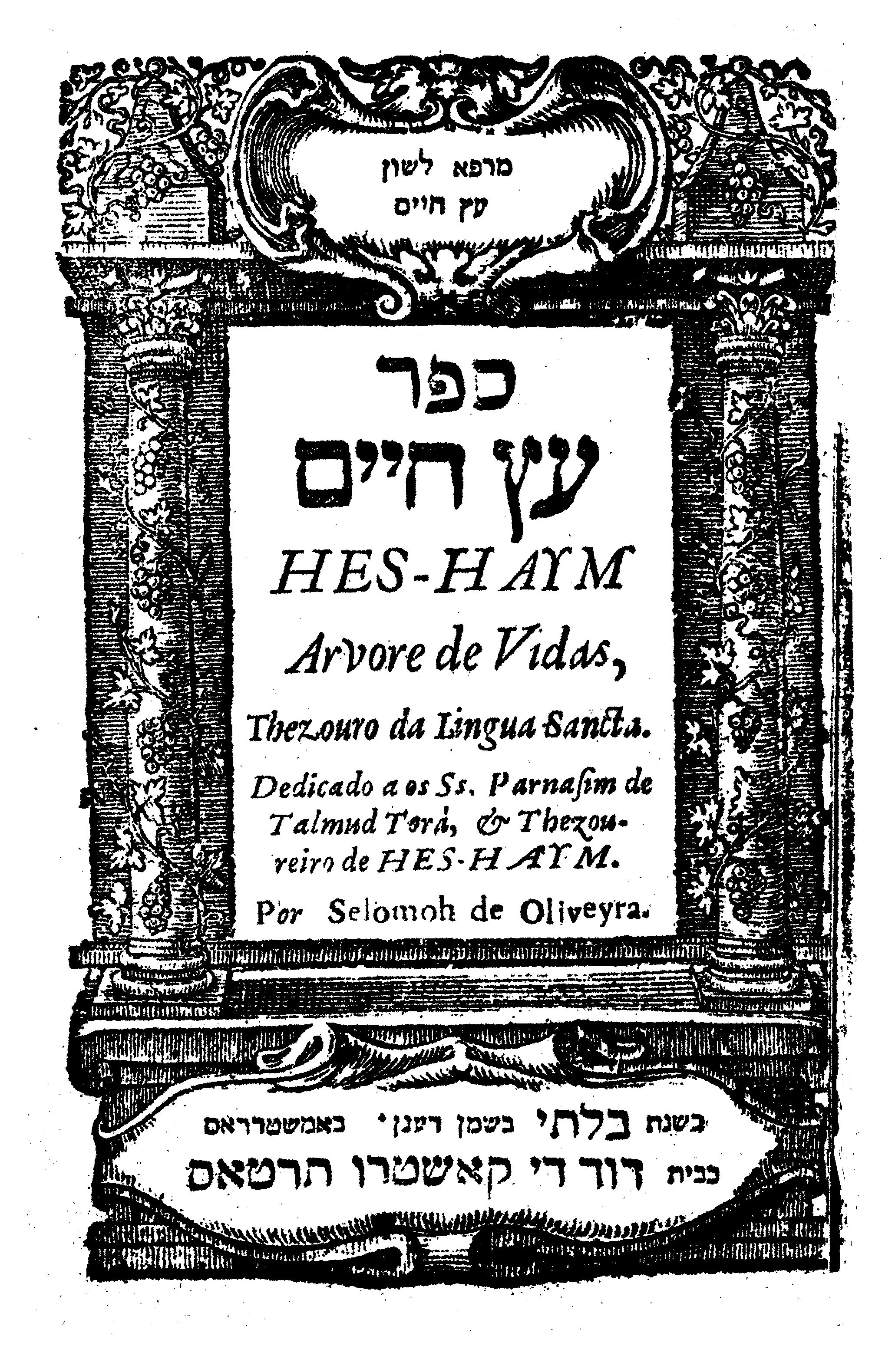

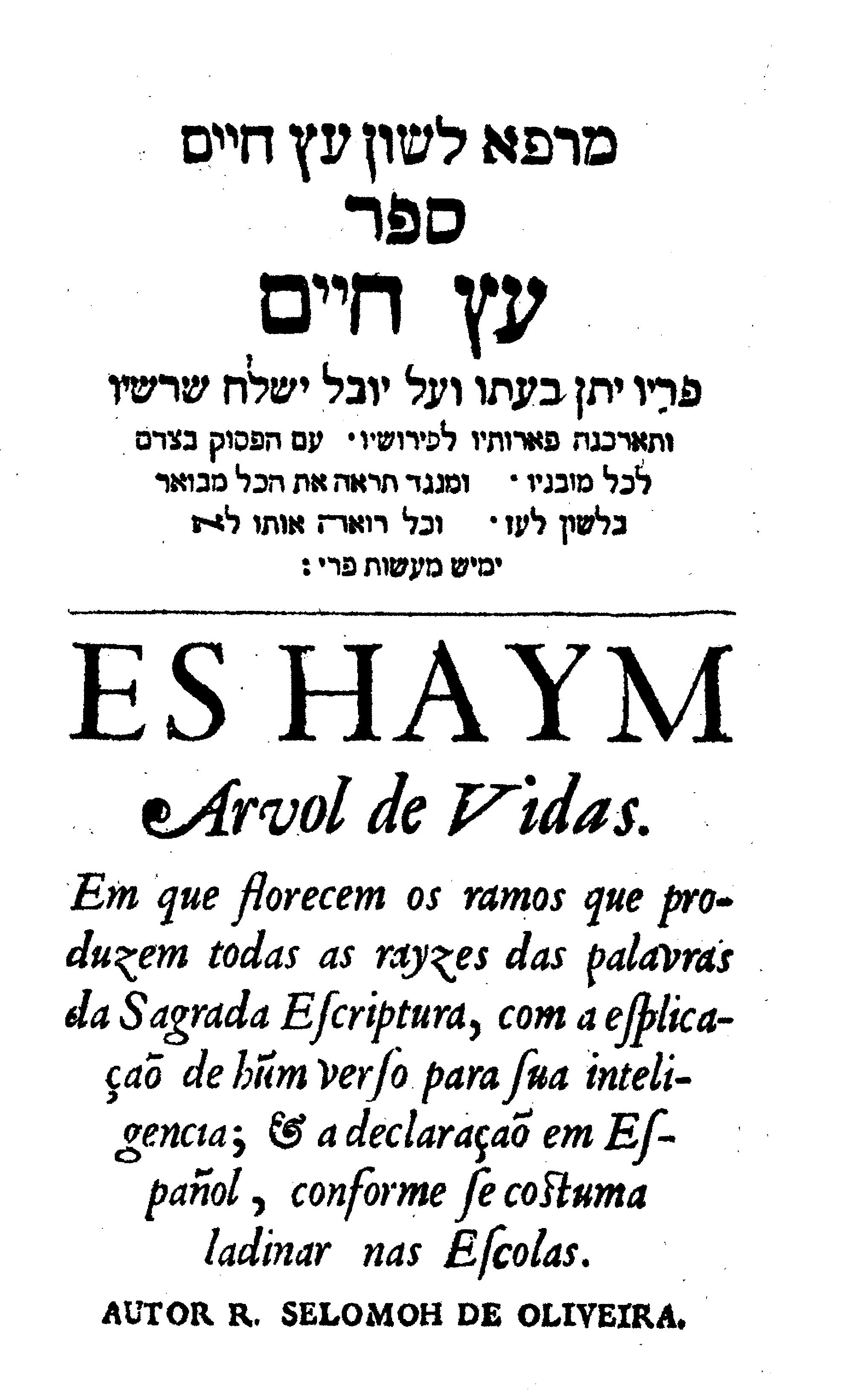

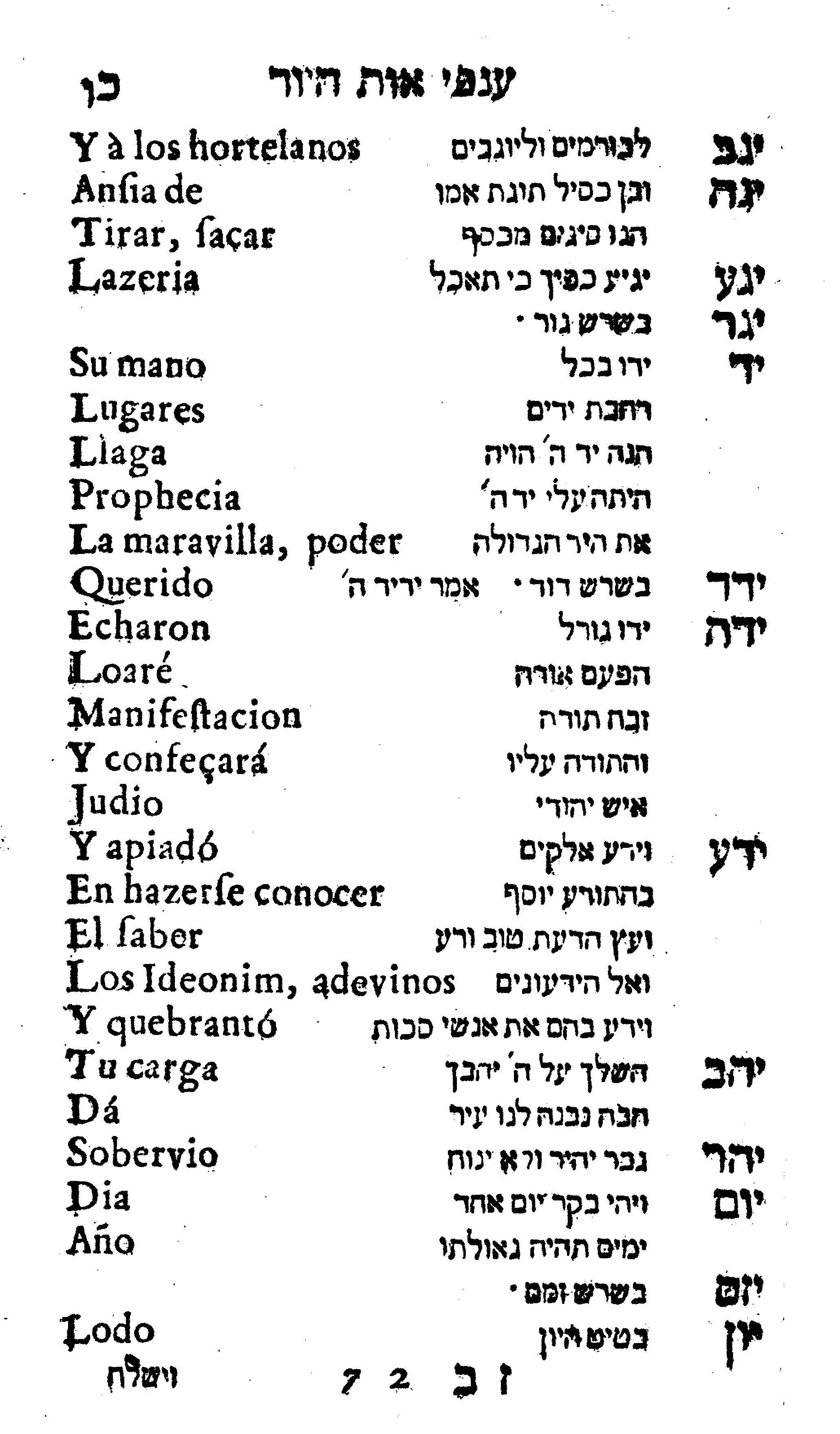

Sefer Etz Hayyim:

Oliveyra's activity as a linguist is reflected in several of his works. In that category is Sefer Etz Hayyim, a Hebrew-Aramaic-Portuguese-Spanish lexicon. This too was published as a sextodecimo (160: [5], 72 ff.) by Tartas. It is dated “I was saturated with ever fresh oil בלתי בשמן רענן )442 = 1682)” (Psalms 92:11). The title-page, with the Tartas pillared frame, has the header “A healing tongue [is a tree of life]” (Proverbs 15:4). The text, bilingual, states that it is: (Deuteronomy 33):

Sefer

Etz Hayyim

Hes Haym

Arvore de Vidas,

Thezouro da Limgua Sancta

Dedicado a os Ss. Parnasim de

Talmud Torah, & Thezou-

Veiro de HES-HAYM

Por Selomoh de Oliveyra

Courtesy of Hathi Trust

The subtitle, Arvore de Vidas, is Portuguese for tree of life. In contrast, Oliveyra’s introduction has the heading Arvol de Vidas, Spanish, also for tree of life. The Portuguese text on the title-page states that it is a thesaurus of the holy language (Hebrew) dedicated by Solomon de Oliveyra to the parnasim (governors, trustees) of the Talmud Torah Etz Hayyim. The title-page is followed by a dedicatory page to the noble parnasim of the Talmud Torah, here six members are named.19

Next is a prologue, and then a second more detailed bilingual title-page, followed by the text. The first section, generally in three columns organized alphabetically by the Hebrew term, reading from right to left, consists of the Hebrew word, a brief explanation in Hebrew of the subject term, and the Spanish translation. Occasionally, when necessary, synonyms appear. This is followed by a section with Aramaic terms organized in the same manner as the Hebrew section. Sefer Etz Hayyim is a highly functional work, as valuable today as it was in the seventeenth century.

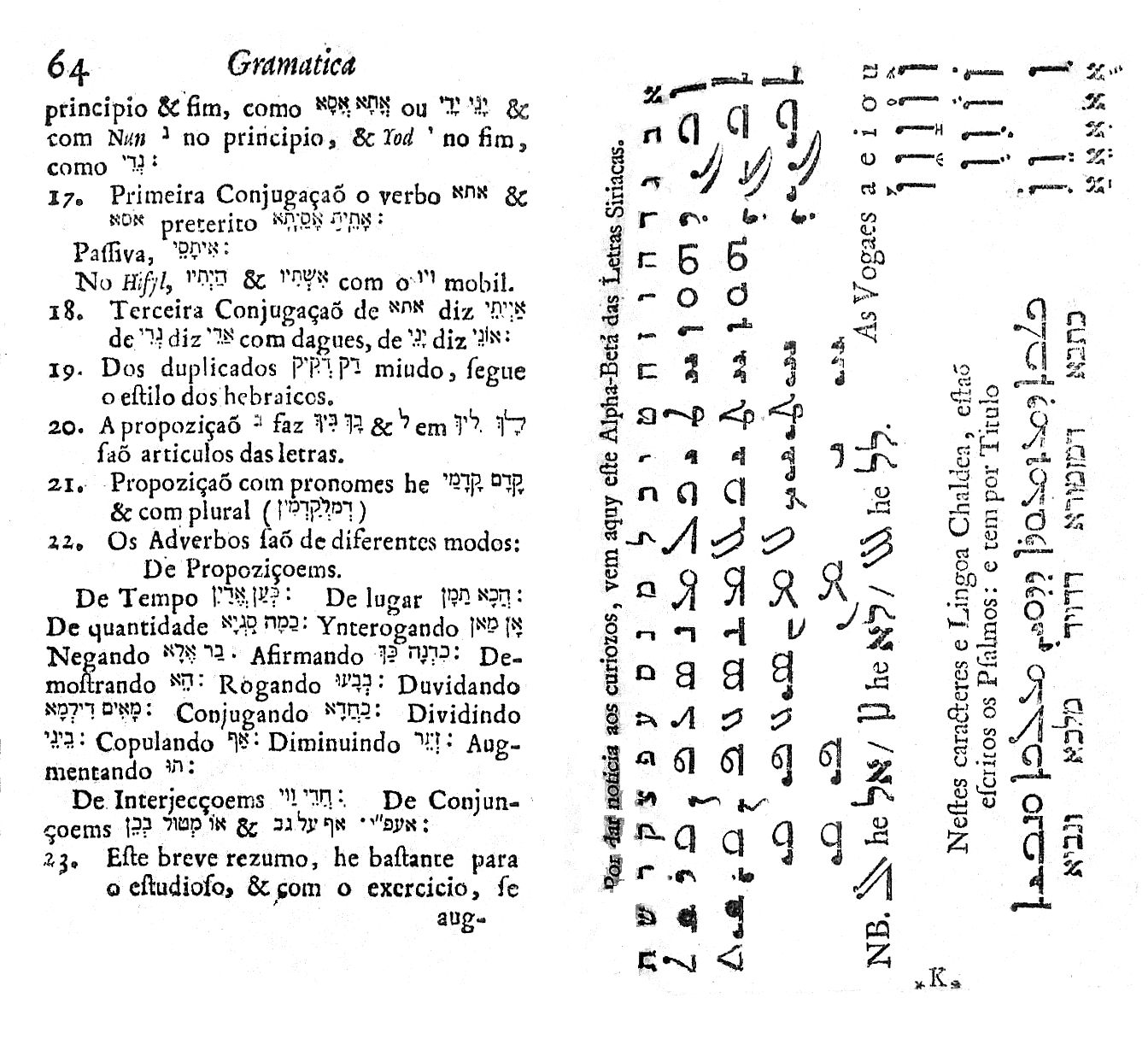

Livro da Gramatica Hebrayca & Chaldayca:

Another grammatical work by Oliveyra, printed in the same year as Sefer Etz Hayyim, is Livro da Gramatica Hebrayca & Chaldayca. Also published as a sextodecimo (160: [8], 71, [11] pp.) by David Tartas in 1688, this latter title is comprised of two combined works on Hebrew and Aramaic grammar in Portuguese. The title page of Livro da Gramatica Hebrayca has the same frame as Oliveyra’s Ayyelet Ahavim (see figure). There is a Hebrew heading with the title Yad Lashon and in smaller letters Dal Sefataim. The text of the title page, in Portuguese, states that it is Livro da Gramatica Hebrayca & Chaldayca Estilo breve & facil. and that it is dedicated to the parnasim of the Talmud Torah & Thezoureyro de Hes-Haym.

1688, Livro da Gramatica Hebrayca & Chaldayca

Courtesy of Virtual Judaica

The title page is followed by a list of books by Oliveyra, verse in Hebrew on the order of the seasons in months in their (zodiac) constellations and the stars in their orbits, and a dedication to the parnasim of the Talmud Torah & Thezoureiro [sic] de Hes-Haym. There are separate unadorned title pages for each part of Livro da Gramatica.

Yad Lashon is the first part, described as Gramatica Manual da lingua Hebraica . . . dated 18 Heshvan 5449 (Thursday, November 11, 1688). It begins with a prologue, followed by the Hebrew grammar in Portuguese with accompanying Hebrew. The text includes exercises and concludes with Hebrew language charts. The second part of Livro da Gramatica is Dal Sefataim, Gramatica Breve da Lingua Chaldaica, dated 5442 (1682). The composition of the Chaldaic grammar section is the same as of the Hebrew grammar, concluding with the rules of grammar ([72]) and a Hebrew-Portuguese lexicon. There is an unpaginated table of the old Letras Siriacas (Syriac) after p. 72. Pagination for the two parts is continuous.

Oliveyra was the author of a series of small books on Hebrew grammar and versification, Livro da Gramatica being the final book. Fuks notes that these books were written and printed over several years. Today, they are generally bound together, resulting in a lack of uniformity between volumes and bibliographic descriptions. He also informs that Ets Haim, the Sephardic society for tuition, purchased two hundred and fifty copies at fifty cents a copy for the school.20

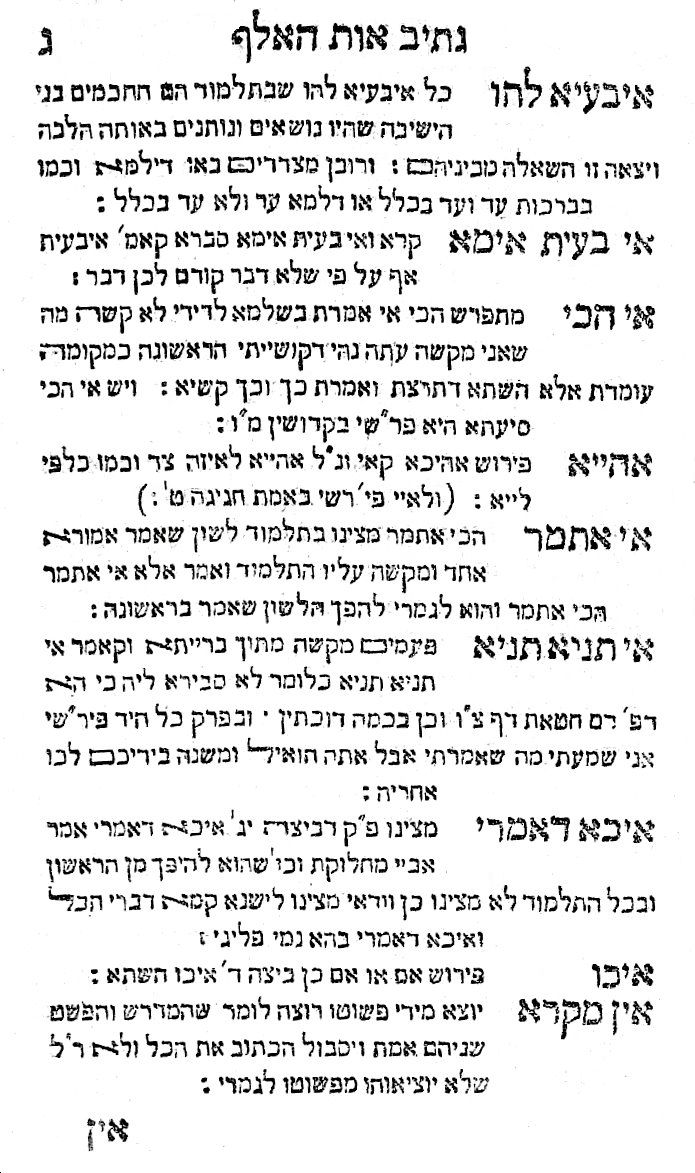

Darkhei No’am:

On Talmudic terminology by R. Solomon ben David de Oliveyra, also in duodecimate format (160: 48, [3], 28, [4] ff.) and published in 1688 by Tartas. Here, too, the title page has the Tartas architectural border and states that it is Darkhei No’am, “ways of pleasantness,” (Proverbs 3:17),

They “are pure words” (Psalms 12:7) and a general index to come to the “entrance of the gate” (var. cit.) to learn the Talmud and at the entrance enter “the place of the [inner] gate” (cf. Zecharia 14:10).

The title page is dated הת"מג in the month of Sivan (448 = between May 30-June 28, 1688), and states “He that walks uprightly בתום (448) walks surely (Proverbs 10:9).” Oliveyra’s introduction follows, beginning, “Her ways are ways of pleasantness, and all her paths are peace” (Proverbs 3:17), explaining that the Talmud is divided into the Mishnah (which is comprised of tractates), and its commentary, which is the gemara. The Mishnah is called Torah she-be’al peh (oral law), and it is the foundation of the Torah transcribed from the time of Moses until Rabbenu ha-Kadosh (Judah ha-Nasi, late 2nd-early 3rd century) for which there was a tradition from the time of Joshua. Oliveyra explains that there is a twenty-one part division consisting of Tosefta, Baraita, responsa, and so forth, for which there are signs and orders, all here addressed. The work is divided into eight netivot (pathways), for example, netiv ha-Mishnah with twenty-six kellalim (rules); netiv ha-kushia (difficulty); forty-seven kellalim; netiv ha-metarez (explanation) in three ways: terutz twenty-five kellalim, hazorah (repetition); and three kellalim.

The text follows, in alphabetic order, set in a single column in square letters, except for the final pages which are in rabbinic type. Printed after the text of Darkhei No’am is Tuv Ta’am ve-Da’at on Hebrew cantillation and the fourteen kellalim of Maimonides concerning the mitzvot. Generally bound with Darkhei No’am, is Darkhei Ha-Shem, an alphabetical index of the 613 commandments, by Oliveyra. The colophon of this last work gives the printer’s name as Uri Phoebus ha-Levi. Fuks enumerates it separately, in contrast to Benjacob and others who list these works together.

1688, Darkhei No’am

Courtesy of R. Shimon Hook

Darkhei No’am is a small work, measuring about 14.5 cm. It has been variously listed as an octavo (Fuks, Steinschneider), a duodecimo (Benjacob), and a sextodecimo (JNUL). The latter is most likely correct, this being an example of half-page imposition, in which a sheet is printed and cut in the middle to form two separate gatherings. This is the only edition of Darkhei No’am.

As noted above, Oliveyra worked on several titles printed at the press of Uri Phoebus. Among them are Tikkun Erev Rosh Hodesh (prayers to be recited on the eve of Rosh Hodesh, 1666), in which Oliveyra’s name appears in the colophon. In addition to the works described above, Oliveyra contributed to or worked on several additional titles. He wrote approbations, discussed below, and both wrote and added to yet further books. Among them are a Tiun Erev Rosh Hodesh (1666), a small volume, a duodecimo (120: 24ff.), prayers for the beginning of the new month; a Mikrei Kodesh (1670), also a duodecimo (120: [12] ff.), chronological tables for converting Hebrew dates into secular dates which Oliveyra informs in the introduction that he wrote in Spanish and translated into Hebrew; a Hamishah Homshei Torah with Megillot, Haftarot, and calendar, this with verse by Oliveyra on festivals (1679-80); another Hamishah Homshei Torah with Rashi, Targum Onkelot, and other commentaries, and a laudatory poem in R. Joseph Bass’s Siftei Yewswhenim, (1680), all printed at the press of Uri Phoebus. Another Hamishah Homshei Torah with Megillot and Haftarot with verse by Oliveyra at the end (1659), printed at the press of Joseph Athias.21

II

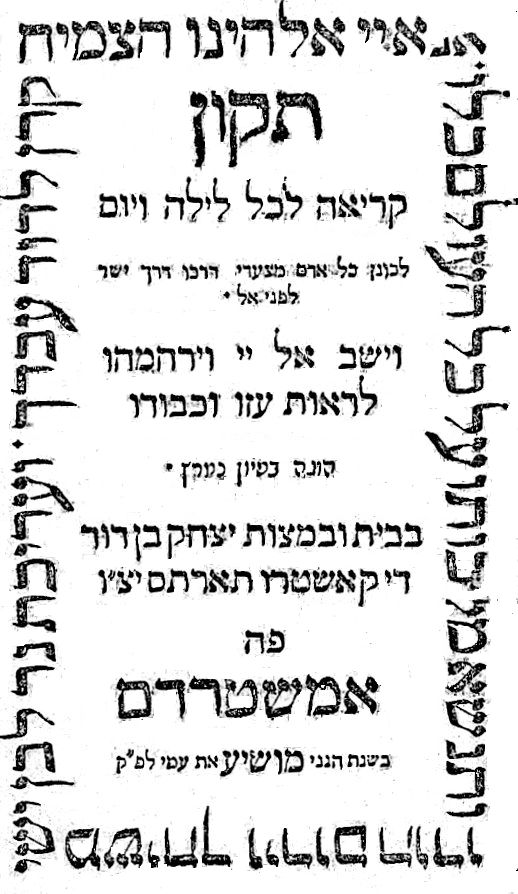

Tikkun Kriah le-Yom ve-Lilah:

Oliveyra, as noted above, was a supporter, advocate of the pseudo-messiah, Shabbetai Zevi (1626–1676). Shabbetai Zevi was the central figure in what has been described by Gershom Scholem as “the largest and most momentous messianic movement in Jewish history.”22 According to Fuks “the tidings of the appearance of the pseudo-Messiah Shabbetai Zevi in Turkey caused a frenzy of messianic expectations in Jewish Amsterdam in 1666.” While several Amsterdam printers published Sabbatean works, Tartas printed the majority of the prayer-books and special texts for that movement, both in Hebrew and Spanish, related to the appearance of the pseudo-messiah and the “imminent redemption of the Jewish people.”23

Among the Shabbatean titles that Oliveyra was involved with are Tikkun Kriah le-Yom ve-Lilah, penitential prayers to be recited day and night, reputedly compiled by Nathan of Gaza (c. 1643-80), the prophet of the pseudo-messiah. Several editions were printed by Tartas, at least two duodecimo editions, a (120: 54, 32 ff.), and a (120: 94, [2] ff.) in 1666. Some editions of Tikkun Kriah have two title-pages, a copperplate engraved portrait of Shabbetai Zevi, enthroned as the Messiah on the throne of King Solomon, holding a scepter, with four angels holding a crown on his head that says “ateret zevi (a crown of glory)” (Isaiah 28:5) and as a king with men at his side seemingly chanting hymns in his honor. On the side of the steps to the throne are lions and below on the steps is the verse “In those days, and at that time, will I cause the Branch of righteousness to grow up unto David; and he shall execute judgment and righteousness in the land.” (Jeremiah 33:15). Below is a large table with twelve men learning and an oversized thirteenth man, representative of the twelve tribes and the Messiah, learning, surrounded by a multitude of men and women and the verse “Thou shalt meditate therein day and night (Josuha1:8).24

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

1666, Tikkun Kriah le-Yom ve-Lilah

Courtesy of Jewish Encyclopedia

The textual title-page informs that it is a tikkun to be recited every day and night and that its purpose is to direct every man so that his steps will be in the straightforward way before God “‘and let him return to the Lord, and he will have mercy upon him’ (Isaiah 55:7) to see his strength and glory.” It is dated “Behold, I will save מושיע (426 = 1666) my people” (Zechariah 8:7), an allusion to Shabbetai Zevi.

There is an introduction by Oliveyra, beginning that it is a day of good tidings and mentioning in the text that the tidings are formal, concluding “in order to redeem our souls from captivity the Lord God gave us ‘a crown of glory (ateret zevi)’” (Isaiah 28:5). Gershom Scholem notes that this is in contrast to the compositions of R. Isaac Aboab and others which are composed in traditional style and lack direct reference to their “immediate occasion.” Scholem describes Oliveyra’s contribution as “rhymed and also more explicit. Oliveira, who was a well-known poet, or rather rhymester, composed a special confession of sins for the afternoon services preceding the eve of the First of Adar I, which was subsequently included in some of the tiqqun that appeared during the summer of 1666. He also composed “a prayer of supplication, containing details regarding the Redemption.”25 In later editions, printed after July, 1666, Oliveyra added the sentence “And now behold a new thing came to us from Safed, and I gave myself no rest until I had laid it before you.”26 There is also an epilogue from Oliveyra.

Tikkun Kriah was also printed and reprinted by both Athas and Uri Phoebus as well as in several other locations, and widely distributed. Although Nathan of Gaza’s name does not appear on the title pages of the Hebrew books it can be found in one Spanish edition. Many copies have two title pages; the first a copper-plate portrait of Shabbetai Zevi, holding a scepter, enthroned as the Messiah on the throne of King Solomon, with a crown that says “ateret zevi (a crown of glory)” (Isaiah 28:5). The second title page repeats the admonition given above, informing that it is a tikkun to be recited on a regular and recurring basis so that they may better serve the Lord and He will have compassion on them. It is dated “Behold, I will save (1666 = 426) מושיע my people” (Zechariah 8:7), an allusion to Shabbetai Zevi.

The popularity of the Tikkun Kriah work reflects the widespread enthusiasm for Shabbetai Zevi at the time, as noted in a postscript in one of the many editions of the tikkun, as reported by Gershom Scholem. He writes that either the printer or corrector states that although he has printed the tikkun previously, due to the haste and the number of people urging him to complete the work that they might “read in it day and night as commanded by our prophet, the man of God that is in Gaza, the misfortunes of every printer befell also me and there are a few errors in the text,” so that he determined to print it again but more slowly.

Oliveyra was among the signatories of a letter of homage to Shabbetai Zevi, but never delivered because the envoys heard of his apostasy while on the way, returning home crestfallen. Scholem writes that “by one of the strange ironies of history, the testimony of faith was signed on the same day that Sabbatai . . .” apostatized.27 28

III

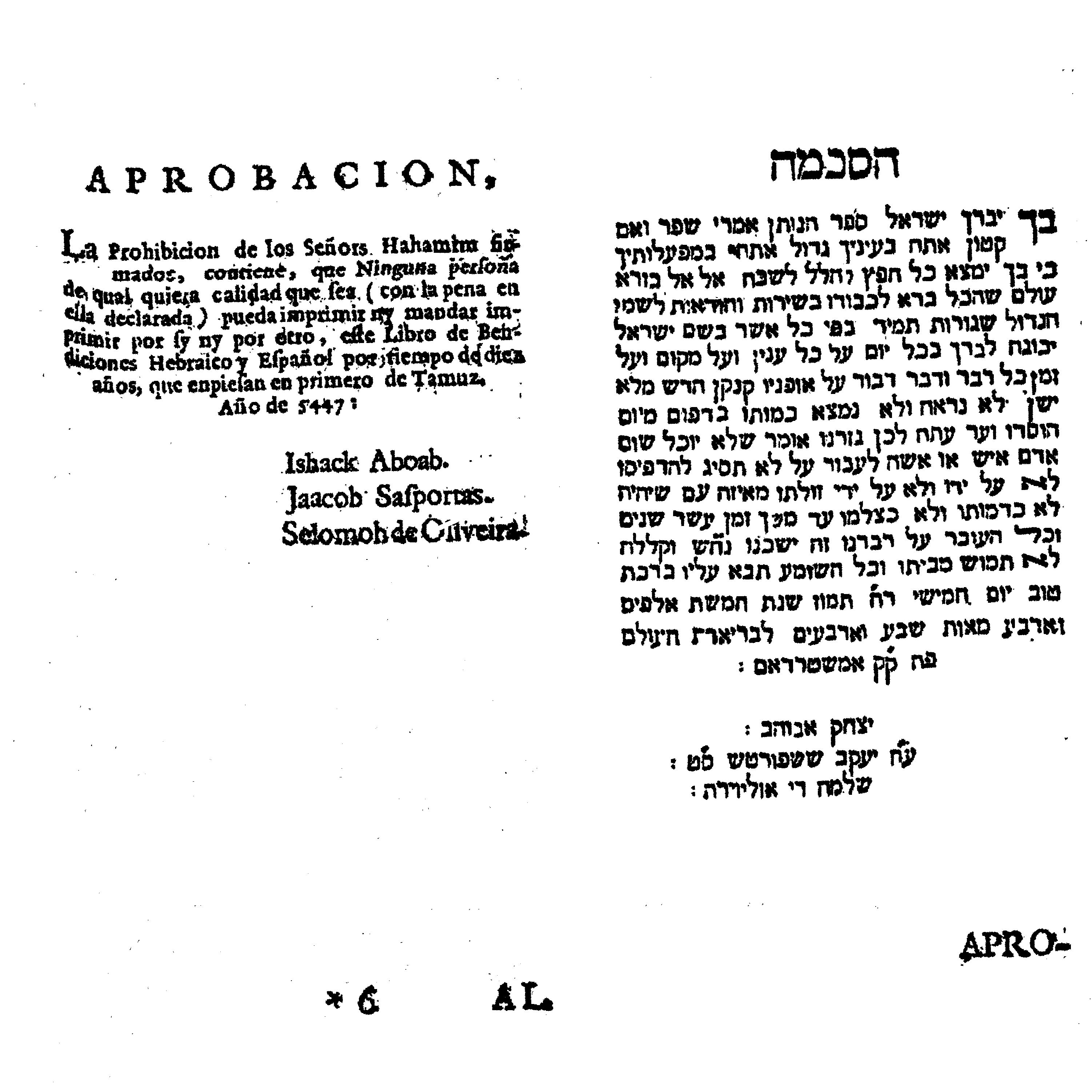

Me’ah Berakhot:

Oliveyra’s importance is evident from the number of books printed in Amsterdam with his approbations. His involvement with Shabbetai Zevi, not withstanding, and having come to an end, he continued to be an individual of importance in the Amsterdam community, as evidenced by the requests for his approbations by leading rabbis. Approbations for books have multiple purposes, among them commendations, indicating approval or praise for the subject work, confirming that a book’s contents do not contain forbidden or prohibited matter, and to protect a publisher’s investment from competitive editions for a fixed period of time.

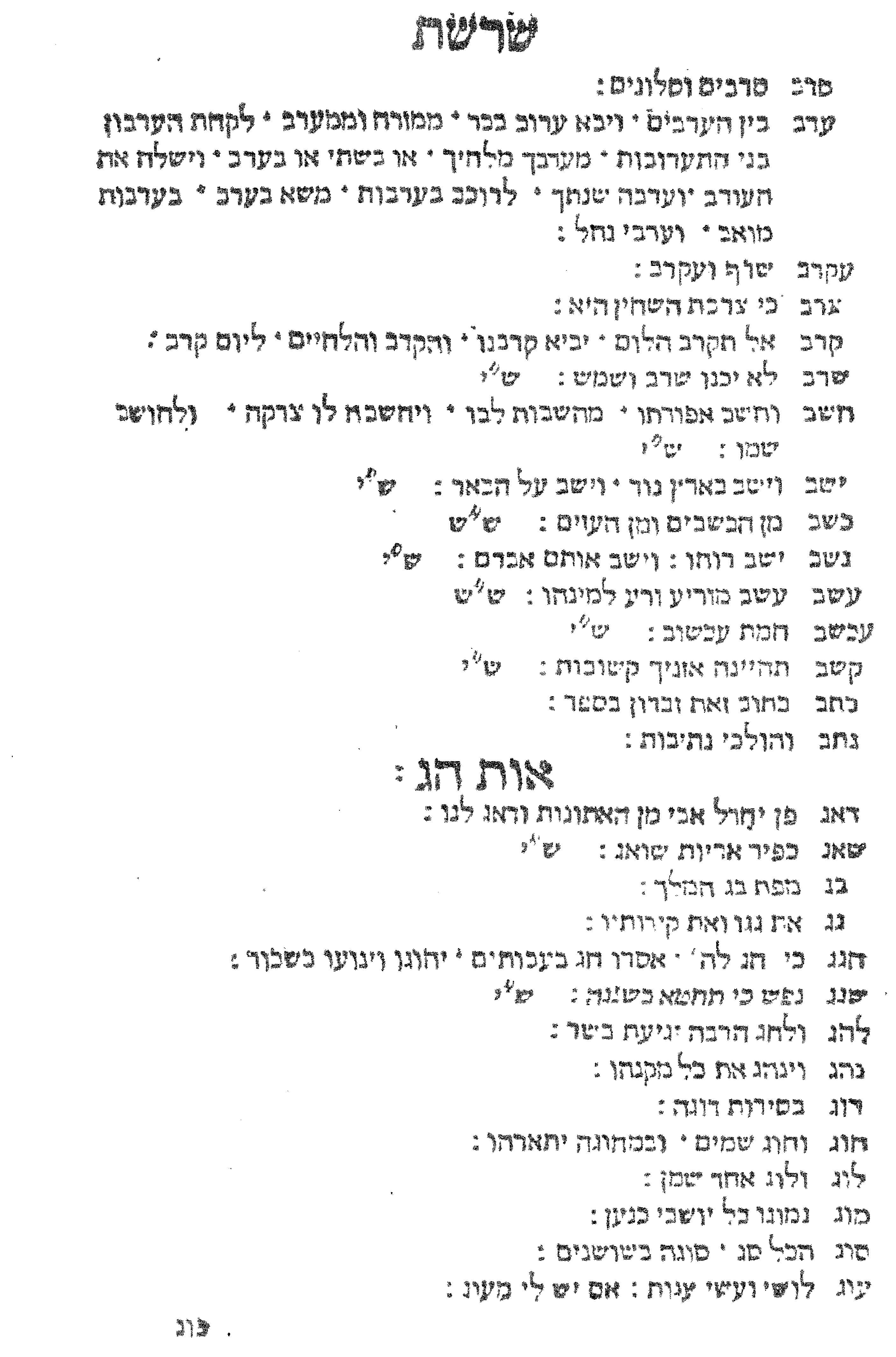

Among the varied works with approbations from Oliveyra are, in order of publishers, Yesh Nohalim (1701); Kizzur Shnei Luhot ha-Berit (1701); Mishneh Torah (1702); Divrei Zikaron (1705); Targum Shir ha-Shirim (1683); Mishnayot Seder Zera’im (1687); Derekh Moshe (1699); Menorat ha-Me’or (1700); Ein Yisrael (1698); Sefer ha-Maggid Nevi’im Rishonim (1699); Perush al ha-Mesorah (1702); Divrei Shemuel (1699); Hesed Shemuel (1699); Zohar Hadash (1701); Hamishah Homshei Torah (1701); Parah Mateh Aharon (1702); Seder Keriah ve-Tikkun le-Liley Hag Shevu’ot ve-Hoshannah Rabbah (1700); Halikhot Olam (1706): and Me’ah Berakhot with Spanish translation (1687, below).

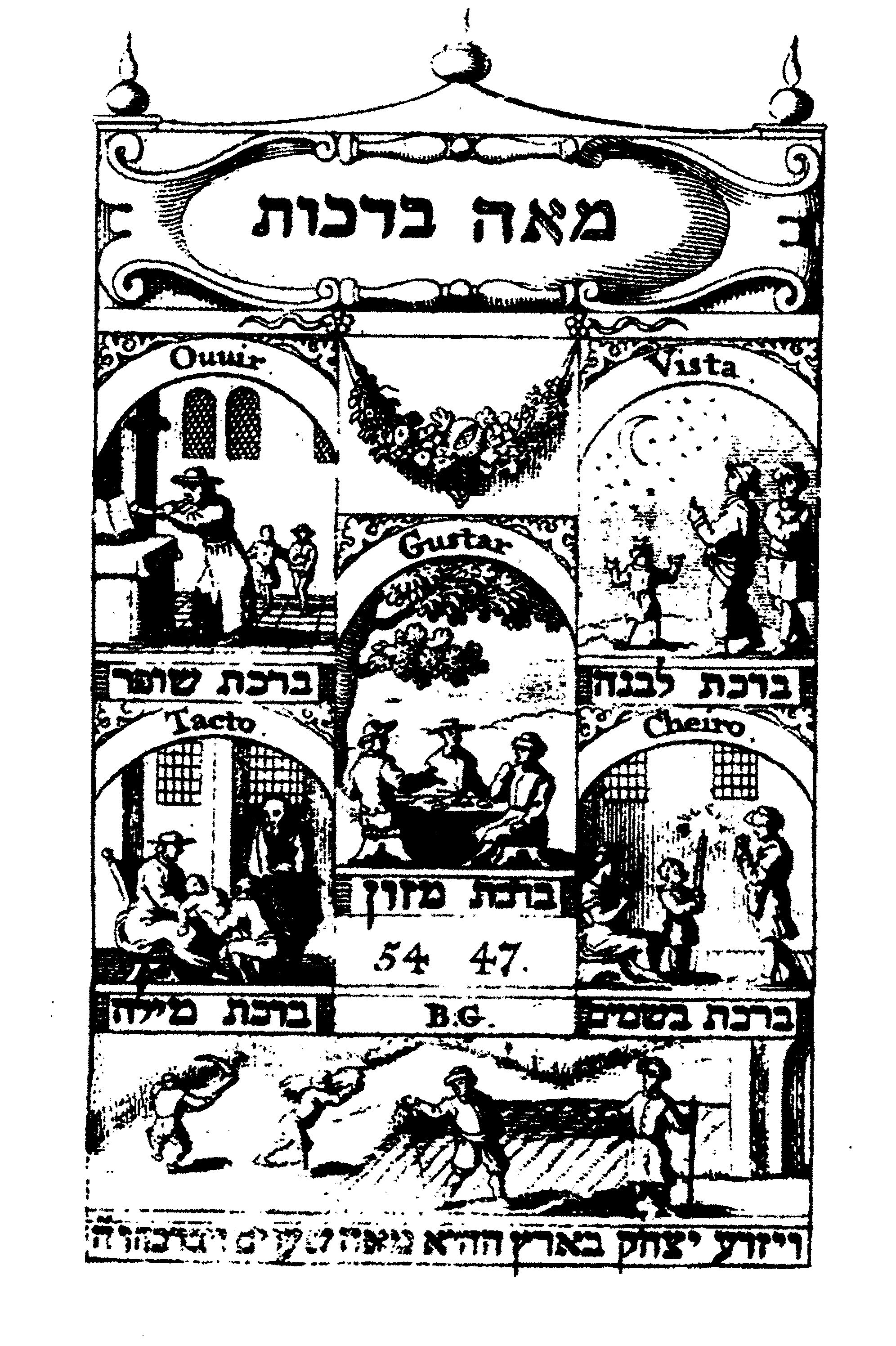

1687,

Me’ah Berakhot

Courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

The contents of these books are varied, encompassing Kabbalah, Talmudic novellae, responsa, and ethical and literary works, all attesting to the value of Oliveyra’s approbation, albeit one of several such commendations to a title. In addition to approving the subject work in his approbation, Oliveyra prohibits rival editions for a fixed period of time, generally ten years.

For example, the approbation for Me’ah Berakhot, Orden de Bendiciones; Y las ocaziones en que fe deven dezir (Order of Blessings; And the occasions in which they must be said) has two title-pages, the illustrated one, above, and a second title-page with a Hebrew header and Spanish text. The approbation has two additional co-signors, R. Jacob Aboab and R. Jacob Sassoon. The approbation is bilingual, the Spanish version shorter, the Hebrew text notes the value of the book and both prohibit its republication by another press for ten years. Just as the approbation is bilingual, appearing on separate pages, so too is there a Spanish title-page. The text of Me’ah Berakhot, is bilingual, set on separate pages, published by Albertus Magnus as a duodecimo (120: xxiii, 303 pp). The Spanish translation is Las Alabancas de Santidad, tradcion de los Psalmos de David (1670-71).29 All attesting to the importance and prestige of Oliveyra.

IV

Oliveyra was, as we began, a multi-faceted person of prominence in his time. Unfortunately, like so many sages over the ages, he is not well-remembered today. Oliveyra stands out, however, as his interests, his expertise, his oeuvre, varies from most other sages, being in literary, poetic, and lexicographic fields rather than rabbinic works, not that he was not also a sage in traditional Jewish literature.

A prolific writer, however, not all of his works are addressed in this article, particularly those without Hebrew text. Additional titles by Oliveyra, noted by Kayserling, and mentioned above, include Calendario Fazil y Curioso de las Tablas Lunares (with the text of the Pentateuch) (1666, 1726); with Circulo de los Tequphot (1687); Enseña á Pecadores Que Contiene Diferentes Obras Mediante las Quales Pide al Hombre Piedad á Su Criador (1666), a Portuguese translation of part of Isaiah Hurwitz's ascetic work; some occasional speeches in Portuguese; and a collection entitled Peraḥ Shoshan, containing various treatises on the fine arts, grammar and logic, the virtues, the festivals, etc., as well as several treatises on the calendar, extant in manuscript.30

Why did Oliveyra write so many bilingual works as well as books entirely in Spanish and/or in Portuguese? Indeed, his orations were primarily in the latter language. Mozes Heiman Gans informs that Portuguese was the language which most of his congregants were familiar with. Furthermore, Gans writes that “in the introduction to the little dictionary he [Oliveyra] published in 1685, Chacham d’Oliveira called Spanish ‘the language into which we usually translate (the Bible and prayers) in our schools’ and Portuguese ‘the language we usually speak.’”31

Oliveyra’s works have not, with the exception of Ayyelet Ahavim (Amsterdam,1776; Vienna, 1818; Harderwijck, 1821) and Ta’amei ha-Ta’amim (Amsterdam 1670,1689, 1732) been republished.32 This does not detract from their value or his achievements. I would suggest two reasons for their not being reprinted. One, to some extent, lies in the changing nature of the community Oliveyra served so well, and for which many of the titles were produced. Bilingual books such as the Hebrew-Aramaic-Portuguese-Spanish lexicon Sefer Etz Hayyim were of considerable value to a converso community not fully familiar with rabbinic texts. However, as the community became more conversant with rabbinic literature, despite Spanish/Portuguese remaining in usage as a vernacular speech, the value of such bilingual texts diminished. Secondly, Oliveyra’s poetic works, as is the case of many other authors’ versified tomes, albeit of value, were not of such value and, indeed, even today remain of limited interest to the larger community.

All of this notwithstanding, R. Solomon de Oliveyra was a profound individual, one who served his community well, occupied rabbinic posts, was highly regarded by his contemporaries, and authored numerous works of value to his congregants, students, and contemporaries.

1 Marvin J. Heller is an award winning author of books and articles on early Hebrew printing and bibliography. Among his books are the Printing the Talmud series, The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book(s): An Abridged Thesaurus, and several collections of articles.

2 Two additional individuals, prominent in their time but barely remembered today, were addressed by Marvin J. Heller in “Moses ben Baruch Almosnino: A Sixteenth Century Multi-Faceted Sephardic Sage in Salonika.” (Sephardic Horizons, 11: 4, Fall, 2021); “Jacob Judah (Aryeh) de Leão Templo: A Converso Scholar, a Jewish Hahkam” (Sephardic Horizons, 12:1, Spring 2022).

3 "Oliveyra, Solomon ben David de." Encyclopaedia Judaica, v. 15, p. 408; L. Fuks and R. G. Fuks-Mansfeld, Hebrew Typography in the Northern Netherlands 1585-1815 2 (Leiden, 1987), p. 247; Mordechai Margalioth, ed., Encyclopedia of Great Men in Israel IV (Tel Aviv, 1986), col. 1264 [Hebrew].

4 Albert Van Der Heide, “Poetry in the Margin: The Literary Career of Haham Selomoh d’Oliveyra (1633-1708),” Studia Rosenthaliana 40 (2007-08), p. 140).

5 Van Der Heide, op. cit.

6 Van Der Heide, pp. 141-42.

7 Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. Listing of Books Printed in Hebrew Letters Since the Beginning of Printing circa 1469 through 1863 I.(Jerusalem, 1993–95), p. 3186 [Hebrew].

8 Meyer Kayserling “Oliveyra, Solomon De,” Jewish Encyclopedia, vol. 9, pp. 394-95. Also see Meyer Kayserling, Biblioteca Espanola-Portugueza-Judaica (1890, reprint with Prolegomen by Y. H. Yerushalmi, New York, 1971), pp. 101-03.

9 The descriptions of several of the titles in this article are extracted, with additions and modifications, from Marvin J. Heller, The Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book: An Abridged Thesaurus I (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2011), var. cit.

10 Fuks, pp. 339-40.

11 Ch. B. Friedberg, History of Hebrew Typography of the following Cities in Europe: Amsterdam, Antwerp, Avignon, Basle, Carlsruhe, Cleve, Coethen, Constance, Dessau, Deyhernfurt, Halle, Isny, Jessnitz, Leyden, London, Metz, Strasbourg, Thiengen, Vienna, Zurich. From its beginning in the year 1516 (Antwerp, 1937), p. 31 [Hebrew].

12 Sextodecimo format refers to the size of book page resulting from folding each printed sheet into sixteen leaves (32 pages). Duodecimo, the format of several other books described here is the book size resulting from folding printed sheet into 12 leaves (24 pages).

13 Van Der Heide, pp. 142-43.

14 Fuks , II p. 352.

15 Mariam Bodian, Hebrews of the Portuguese Nation: Conversos and Community in Early Modern Amsterdam (Bloomington, Ind. 1999), pp. 82-83.

16 The entire eulogy in Hebrew and with English translation is in George Alexander Kohut, “Jewish Martyrs of the Inquisition in South America,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 4 (1986) pp.167-71.

17 Fuks, pp.352-53.

18 The variance in the year, 1665-1666 reflects the fact that the Hebrew calendar year begins several months earlier than the Gregorian solar year.

19 The six individuals are Semuel de Elisah Abrabanel, Iahacob Ximenes Cardozo, Yshac Levi Ximenes, Moseh Alvares, David Ymanuel de Pinto, and Iaacob Fraco da Silva.

20 Fuks, p. 341.

21 Fuks, II var. cit.

22 Gershom Scholem, “Shabbetai Ẓevi,” Encyclopaedia Judaica., vol. 18, Mac, pp. 340-359.

23 Fuks, II pp. 293, 341.

24 A.M. Haberman, Title Pages of Hebrew Books (Tel Aviv: 1969), pp. 55, 129 no. 40a [Hebrew]; Gershom Scholem, Sabbatai Sevi. The Mystical Messiah 1626-1676 (Princeton, 1973), p. 526.

25 Scholem, Sabbatai Sevi. p. 525.

26 Scholem, Sabbatai Sevi. The Mystical Messiah, p. 368.

27 Scholem, Sabbatai Sevi. p. 541.

28 While most of Shabbetai Zevi’s followers returned to normative Judaism there were a number of his disciples who, after his apostasy, followed him and outwardly converted to Islam, practicing a form of Judaism secretly, with practices in serious violation of traditional Judaism. There were several subsects of these groups, Donmeh. Several members of the Donmeh were active in the Young Turk revolution (1909) and it was even suggested that Kemal Atatürk (1881-1938), the first president of Turkey, was of Donmeh origin [not substantiated--A.G.]. There are still Donmeh in Turkey today.

29 Fuks, II var. cit.

30 Kayserling. Jewish Encyclopedia, vol. 9, pp. 394-95.

31 Mozes Heiman Gans, Memorbook : History of Dutch Jewry from the Renaissance to 1940, English translation Arnold J. Pomerans, (Baarn, Netherlands, 1971), p. 104.

32 This refers to the Hamishah Homshei Torah with Tikkun Soferim addressed above.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800