SCOOP: A JEW FROM TURKEY IN QUEBEC CITY BEFORE ESTHER BRANDEAU1

by Nikolas-Samuel Baron Bernier2,3

Figure 1. “The encounter of the Soul-Mates,” Suzan Edith Baron

Lafrenière, 20184

Private Collection of Nikolas-Samuel Baron Bernier and Elizabeth Garcia Carrillo

Everyone in Quebec City knows the picturesque and tragic story of our national Yentl, Esther Brandeau, the young Jewish woman who disguised as a boy and tried to immigrate illegally to New France. She landed at the port of Quebec City in 1738 (Tisdel, Dictionnaire biographique du Canada). But who has ever heard of the incredible story of Joseph Langeron? He was a Jew from Turkey who left eloquent, but discreet, traces in the archives, particularly during his hospitalizations at the Hôtel-Dieu in Quebec City in 1691 and in 1697, as well as in his quixotic duel with the justice system.

Several years ago, I read historian Pierre Anctil’s article “Une présence juive en Nouvelle-France?” (“A Jewish presence in New-France?”). Despite the historical dogma that no other Jewish people had immigrated to early Canada except for Esther Brandeau, I was motivated to search for such a presence. I remain amazed that this is the really first discovery proving that another Jew lived here in this French colony of North America. Both were Sephardic. And I wouldn’t be surprised if we find more in the years to come.

NO TRESPASSING

The French Law of the time strictly stipulates that no Jew has the right to settle in New France, unless he converts to the Catholic religion. There is therefore no official Jewish immigration before the British regime (1760). "The Esther Brandeau (Brandao) affair," kept the authorities in suspense from 1738 to 1739. The expulsion of the young Sephardi woman from the Saint Esprit district of Bayonne at the expense of the king, leads us to suppose that other conversos were able to settle incognito in the colony, without “getting caught.”

The traces of a few exceptional cases of the fate of illegal immigrants or, on the contrary, “legally converted” remain. The earliest appearance found in the list of ships that came to New France was reference to "the Jew" who "signed a solemn protest" concerning a commercial restriction imposed by the English (Trudel, p. 495) and who landed in Quebec on “Le Don de Dieu” (“the Gift of G‑d”) on July 4, 1631.

JOSEPH LANGERON DIT PASSEPARTOUT, “JEW FROM TURKEY”

Considering so many prohibitions on the passage to New France and resigned to the shortage of historical documents on the question, to my amazement I made this discovery one sleepless night. It was downright “throwing me to the ground,”6 especially since I was precisely rummaging through The Dictionnaire généalogique des familles du Québec (Genealogical Dictionary of Quebec Families), a must-read for “origin beggars” by the renowned René Jetté.

A small notice, nothing at all, suddenly became the key opening the door to other manuscripts unearthed during the same night. Here is what I saw appear before my confused and incredulous eyes:

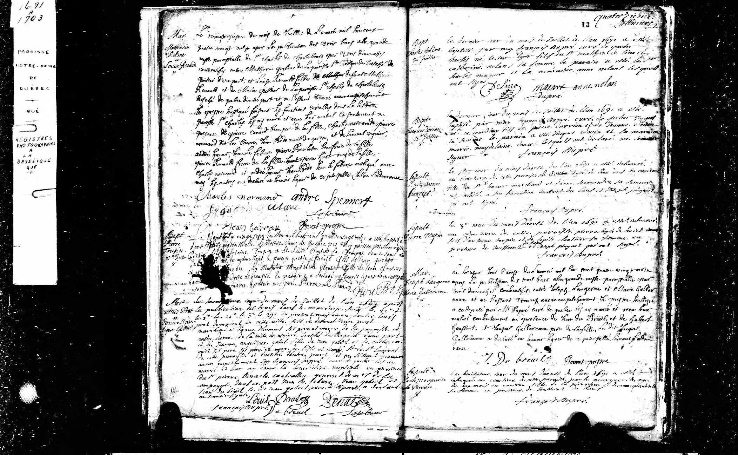

Figure 2. Excerpt from the Genealogical Dictionary of Quebec Families, bottom of page 644.

“LANGERON, Joseph (Assin & Facq CASON) Jewish, from Turkey; cited 11-12-1691

Hôtel-Dieu Québec, 30 years old, Turkish and 11-10-1697 Provence, 39

years old. Mr. 06•08-1691 Quebec (Ct 25-07 Gilles Rageot)”

Continued on the right page was the following, his bride:

“GALARNEAU, Marie-Madeleine (Jacques & Jacqueline HERON) rem. 1701 Jean Deslandes.

WITHOUT POSTERlTY” (Jetté, p.644)

In summary, The Hôtel-Dieu Hospital of Québec City provided medical care at least twice to Joseph Langeron, a Jew from Turkey, whose father was named Assin Langeron and whose mother was Facq Cason (“Jacq” in the document below), first on December 11, 1691, and next on October 11, 1697.

Joseph Langeron was married on August 6, 1691, (actually August 8) to Marie-Madeleine Galarneau, daughter of Jacques Galarneau and Jacqueline Héron (or Néron, see below). Finally, this notice by René Jetté informs us that the couple had no children and that in 1701 Marie-Madeleine remarried a man named Jean Deslandes.

Of course, after reading this report, several questions arose: First, how is it that Joseph Langeron was officially identified as a "Jew from Turkey" given the laws in force in New France? The most logical hypothesis is that he converted to Catholicism. This notion is confirmed by the fact that he and Marie-Madeleine Galarneau had a religious wedding at the Basilique of Quebec City, as I was able to see in their marriage certificate:

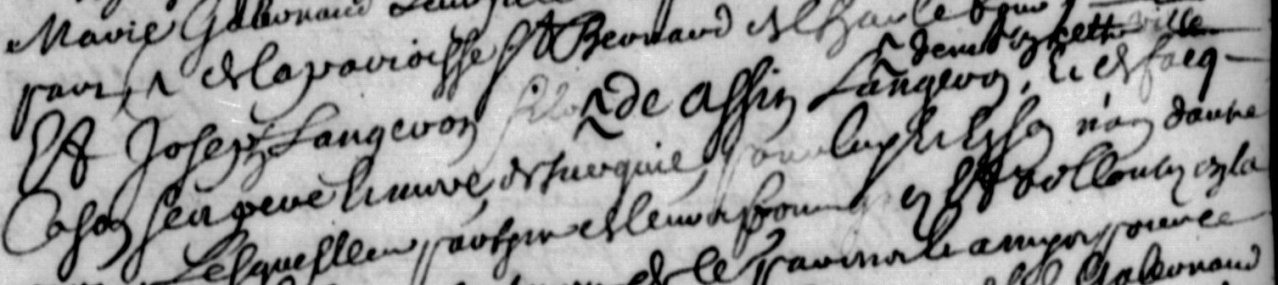

Figure 3. Marriage of Joseph

Langeron and Marie-Madeleine Galarneau, Basilique Notre-Dame de Quebec, August 8, 1691.

Source: Drouin Genealogical Institute.

However, upon further investigation, a doubt arises:

From which original archive(s) did Jetté derive the information that he was a “Jew from Turkey”? And from where did he get the names of Langeron’s parents? No mention of this appears in the religious marriage certificate.

Thus, at all costs, I set out to find the archives of the patients of the Hôtel-Dieu in 1691 and 1697, only to discover that Joseph was treated as a soldier when he entered the hospital. Indeed, by consulting the Programme de Recherche en Démographie historique de l’université de Montréal (PRDH), I found that Joseph Langeron benefitted from an earlier hospitalization on January 1, 1691, of which Jetté does not write. It was also revealed that his nickname is "Passepartout," that he is a soldier by profession, and that he is indeed from Turkey (no. 4 left, which is reconfirmed during the hospitalization of December 11, 1691 ("Turkish nation") (no. 12 right):

Figures 4 & 5. Joseph Langeron, Hospitalisations de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec

Left (no.4 du 1691-01-01, PRDH N0 414749) - Right (no.12 du 1691-12-11, PRDH N0 413048)

Following a lead indicated by Jetté and the PRDH, I came across a register of the notary Gilles Rageot on July 25, 1691. Joseph and Marie-Madeleine had signed a wedding contract before the notary before the religious marriage, as was customary under French law. Then I felt the need to absolutely find the original marriage contract; the names of the parents and the Jewishness of Joseph Langeron must, doubtless, be found in these ancient scribbles on this document or else in the fly-like originals of the registers of hospitalized patients at the Hôtel-Dieu.

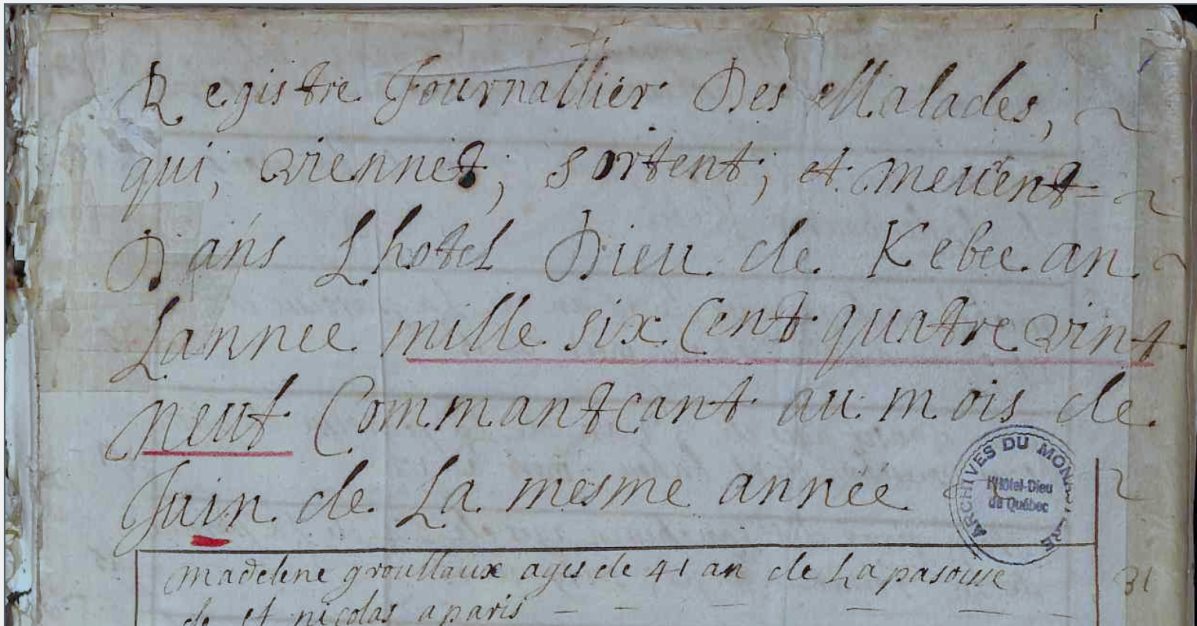

Figure 6. Daily Register of Sickness Who Come, Leave, and Die in the Hotel-Dieu de Quebec (1689-1698), title page (excerpt).

Fonds Hôpital du Monastère des Augustines de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec.

Source: Archives du Monastère Augustinians.

The investigation of the handwritten list of patients hospitalized at the Hotel-Dieu in Quebec in these archives allowed me to retrace Joseph dit Passepartout of Turkey on January 1 of "the year one thousand six hundred and ninety-one” (1691) (p. 83). To my great surprise, his surname appears not as “Langeron” but rather as “Langello” (3rd name in the list of this excerpt).

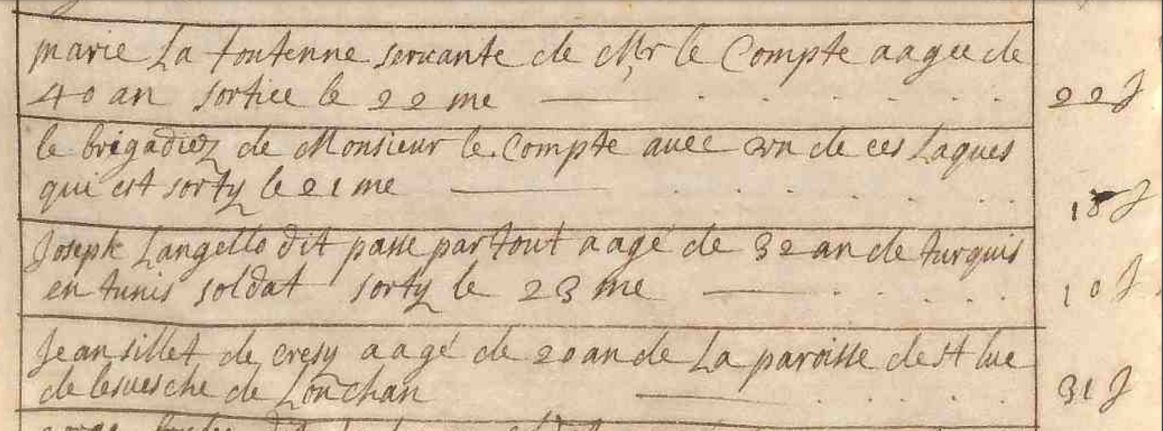

Figure 7. Daily Register of Sickness Who Come, Leave and Die in the Hotel-Dieu de Quebec (1689-1698), p.83.

Fonds Hôpital du Monastère des Augustines de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec.

Source: Archives du Monastère des Augustines.

Despite my interest in these discoveries in the archives of the Hotel-Dieu about our Joseph Langello, who became Langeron of Turkey, his Jewish roots going back to Abraham, Itzkhak, and Yakov were not revealed there.

IN SEARCH OF THE ORIGINS OF JOSEPH

The gold mine of the National Library and Archives of Quebec (BAnQ numérique), more specifically the notarial acts of Gilles Rageot, was my next destination in the search for the marriage certificate. Here, I sought documents in which the names of Joseph's mother and father would appear, as well as the key to his Jewish origin. I also found documents concerning Joseph's legal misadventures (which I will tell you about later) and none of this information is there either.

I placed all my hopes of finding what would indeed consist of direct proof of the presence of a Jew in Quebec before Esther Brandeau in a single notarial document7 comprised of seven thousand, two hundred and eighty-seven pages and covering several years (notary Gilles Rageot 1666-1691). To my knowledge, it would be the only tangible example of a Jew (and not a converso) that settled and lived several years in New France.

ORIGINAL SOURCE FOUND: JOSEPH THE TURK WAS A JEW

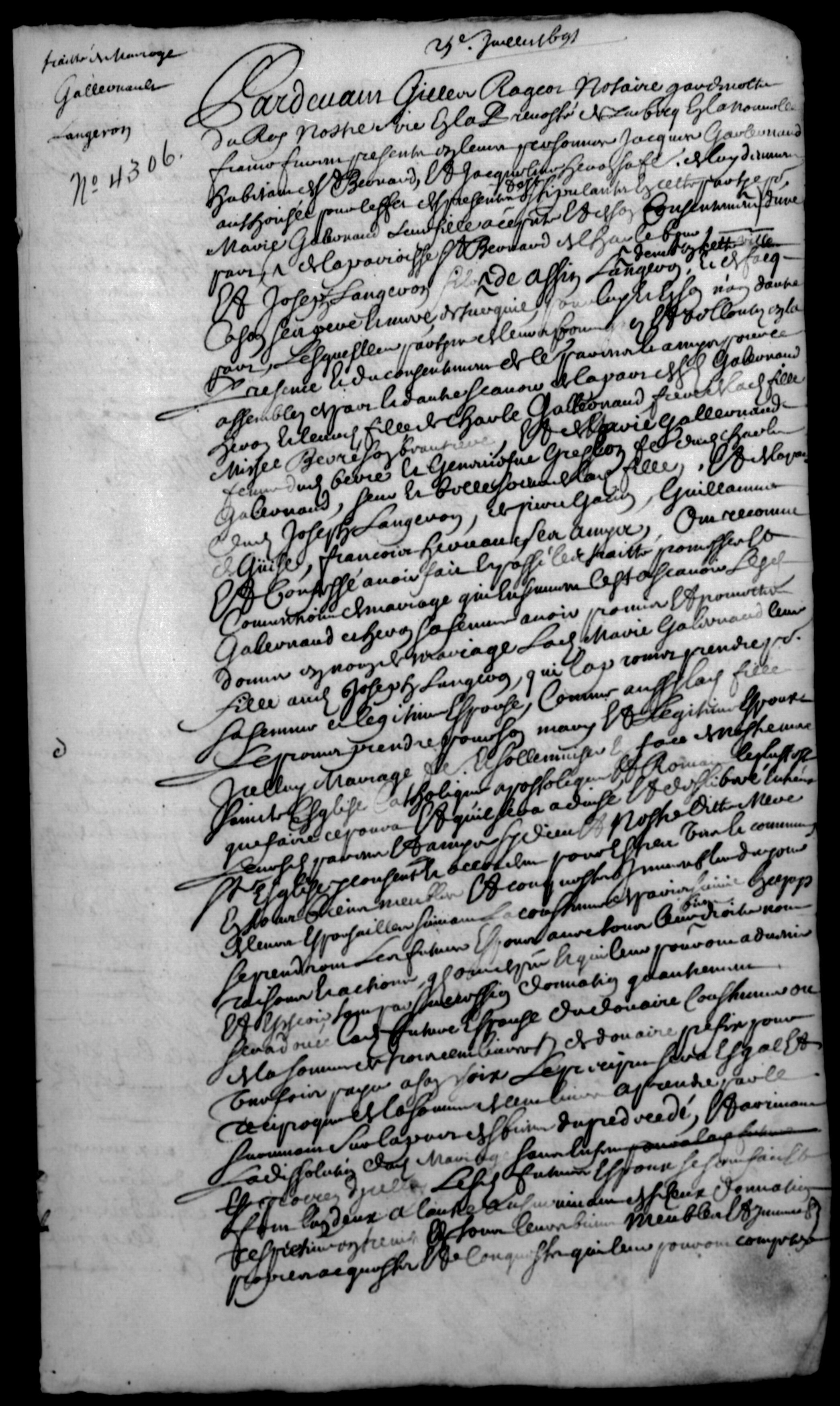

Finally, I found the July 25, 1691, civil marriage of Joseph and Marie-Madeleine containing the written proof that René Jetté was not mistaken:

“(…)et Joseph Langeron, jeuif en cette ville (Québec), fils de Assin Langeron et

Jacq Cason, feu père et mère de Turquie (…)”

“(…) and Joseph Langeron, Jew in this city (Quebec City), son of Assin Langeron and

Jacq Cason, late father and mother from Turkey (…)”

Figure 8. Civil marriage contract of Joseph Langeron and Marie-Madeleine

Galarneau, July 25, 1691

Acts of Notary Gilles Rageot (1666-1691), Notarial act No. 4306

Library and National Archives of Quebec (BAnQ numérique)

Figure 9. Excerpt highlighting lines 8-9 “Joseph Langeron, “Jeuif (juif) en cette ville,” meaning “Jew in this city (Quebec city)”

Civil marriage contract of Joseph Langeron and Marie-Madeleine

Galarneau, July 25, 1691

Actes du Notaire Gilles Rageot (1666-1691),

Notarial act No. 4306

National Library and Archives of Quebec (BAnQ numérique)

For the first time, therefore, there is direct proof of the Jewish presence in New France other than that of Esther Brandeau. Joseph Langello/Langeron is, so far, the first known Jew in Quebec and in Canada.

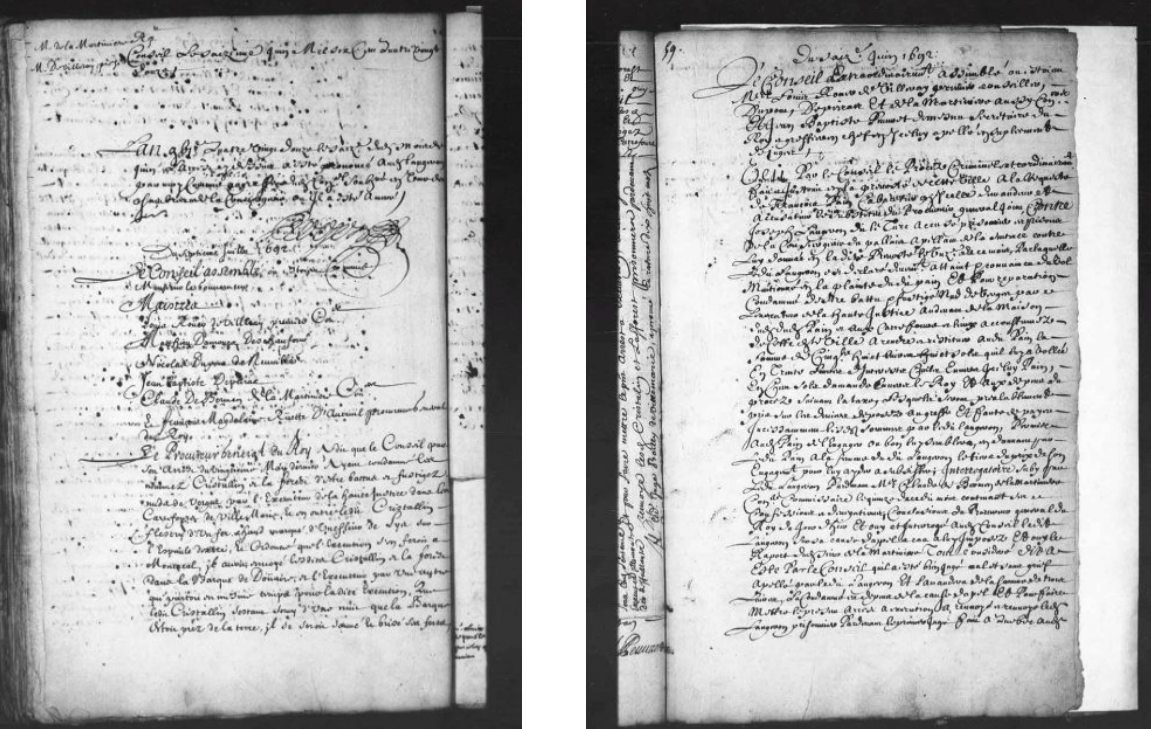

A DUEL WITH THE JUSTICE OF NEW FRANCE

In 1692, Joseph Langeron dit le Turque (meaning “J.L. called ‘the Turk’”), then working as a servant for François Pain, is accused of theft by the latter. He is put on trial and is "sentenced to be beaten and castigated naked, with rods by the Executor of the High Justice (the executioner)..."

Joseph proclaims his innocence and asks for an appeal before the Sovereign Council of New France. He loses his case on June 16, and must, therefore suffer the punishment.

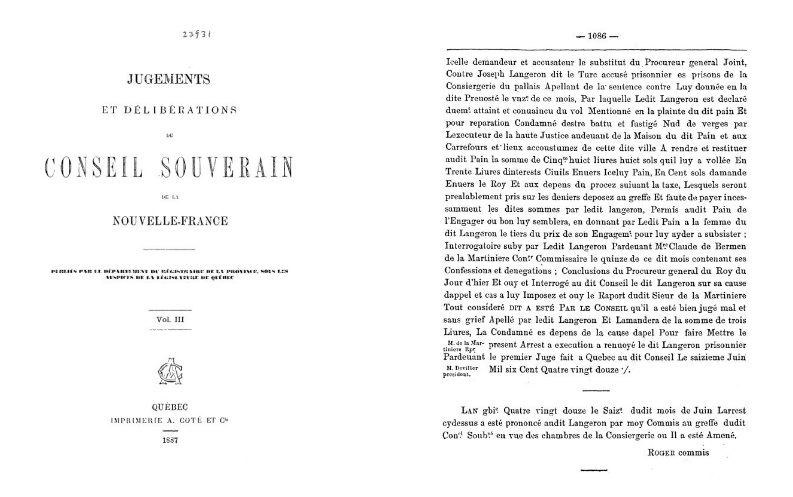

Here is the judgment and the request for failed appeal (digital BAnQ, followed by a transcript): "Sentence declaring that it was judged well in the Provostship of Quebec against Joseph Langeron said the Turk accused of having stolen François Pain, innkeeper,” and then "Judgment declaring that he was judged well and badly appealed …".

Figure 10. Judgment declaring that he was rightly judged and wrongly called by

Joseph Langeron dit le Turc

accused and prisoner of the Palace concierge, appealing from a sentence rendered to the Provostship,

declaring him convicted of the theft mentioned in François Pain’s complaint, innkeeper of Quebec - files 1 to 2.

Judgments and deliberations of the Sovereign Council of New France, June 16, 1692

National Library and Archives of Quebec (BAnQ numérique)

Figure 11. Judgments and Deliberations of the Sovereign Council of New France (Transcription) Vol. III

Department of the Registrar of the Province of Quebec, 1887, cover page and p. 1086.

THE MYSTERY OF THE END

It is unknown what precisely happened to Joseph Langeron afterwards. The mystery still hovers around his last appearance in the archives of the Hotel-Dieu on October 11, 1697, since the name and the age indicate that it is very probably the same individual, but it is written that he is “Provençal.” Would he have migrated to France and then returned to Quebec before dying? We know that during her second marriage to Jean Deslandes in 1701, Marie-Madeleine Galarneau was a widow (see Wedding act of Marie-Madeleine Galarneau (Widow) and Jean Deslandes, October 24th 1701, Quebec City, PRDH N° 47821).

If we have discovered the wake of the passages in New France of Joseph Langello/Langeron, known as Passepartout, a Jew from Turkey and of Esther Brandao/Brandeau, a Portuguese Jew from Saint Esprit (Bayonne), other Sephardim lost in the migrations of history may be waiting for us to patiently dust off a few kilometers of archives in order to release and let their sparks shine.

1 This article appeared previously in French in the Times of Israel, 1-9-2023, https://frblogs.timesofisrael.com/conversos-en-nouvelle-france-ont-ils-cree-des-reseaux/

2 Nikolas-Samuel Baron Bernier is a biologist, actor, and editor for an educational service founded to popularize Jewish scientists who have been ignored or misunderstood in the history of science. He has published articles in the field of biomedical research and molecular neurobiology in various professional publications. More recently, he was involved in the development of the family business, Baron Lafrenière Lawyers and was also an agent for his mother, the artist Suzan Edith Baron Lafrenière. Nikolas lectures on the history of Judeo-conversos, Crypto-Jews and b'nai anusim to the general public.

3 Thanks to my daughter, Cassandre Madeleine Montreuil-Bernier, and my nephew, Jaime David Torres Garcia, for their help with research in the National Library and Archives of Quebec (BAnQ numérique) while I was abroad. Thanks to Sonia Sarah Lipsyc for her advice and encouragement. And thank you also to my father, Michel, and my mother, Suzan Edith, for having transmitted to me their passion for history and the patience of scientific and legal rigor. Many thanks to Pierre Anctil and Simon Jacobs for their book The Jews of Quebec: 400 Years of History (Pierre Anctil and Simon Jacobs, PUQ, 2015) in which Pierre Anctil's article, "A Jewish presence in New France?” gave me the motivation to search the archives for this Jewish presence in Canada before 1760. In closing, thank you also to Mr. Jean-Marie Gélinas for having published his article, "A well-kept secret," in the Voix Sépharade (Dec. 2003) and for having, in a way, paved the way for research on hidden Jews (from 1973) in the History of New France.

4 This painting is the work of artist Suzan-Edith Baron Lafrenière (SEBL), the author’s mother. Thank you for lending the image of her original works of art.

5 Trudel, Marcel, 1966, Histoire de la Nouvelle-France, vol. 2, Montréal: Fides.

6 This pun, “throwing me to the ground,” only makes sense in French, since this discovery was “à m’en jetter par terre”!)

7 Notary Gilles Rageot, 1666-1691.