The Albelda Family: Moses Albelda and Moses ben Jacob Albelda:

Prominent, Eminent, Scholars

by Marvin J. Heller1

Figure 1. Reshit Da’at Crowns 1, 1583

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

The Albelda family produced eminent scholars, among them Rabbi Moses Albelda (d. 1549), originally from Spain, co-author of a super-commentary on Rashi, and R. Moses ben Jacob Albelda (c. 1478–c. 1560), a prominent and highly regarded sixteenth-century scholar. The latter’s life was complex, unsettled, punctuated by wandering and suffering, with considerable hardship, but also highlighted by substantial achievement. Moses ben Jacob Albelda was the author of several books; the works of both authors are addressed in this article.2

The name Albelda is likely from a town in old Castile, in the location of Logrono, where Jews were resident as early as the eleventh century. R. Moses Albelda (Albeilda), the elder of our Albeldas, was likely one of the exiles from Spain in 1492, according to Shimon Vanunu. He settled in Salonika at about the beginning of the sixteenth century and was appointed, as one of the leaders of the Salonika community, residing there until his death in 1549 when elderly. Moses Albelda was the author of a super-commentary on Rashi, published together with other commentaries in Constantinople (c. 1525), discussed below.3

R. Moses ben Jacob Albelda is the primary subject of this article; his varied works are addressed below. Both Meyer Kayserling and Shimon Vanunu suggest that he was the above Moses Albelda’s grandson. Steinschneider writes forsan nepos (perhaps a nephew). His father was also a Torah sage as R. Solomon Atia informs in his commentary on Psalms. Moses ben Jacob Albelda served as a preacher in Arta, Greece. A decree he issued in 1534 together with R. Menahem prohibiting mixed dancing resulted in his leaving Arta. Albelda subsequently served in the rabbinate in Valona (Avlona or Vlora), Albania, for ten years and afterwards in Salonika. Kayserling informs that this Albelda has been described “as a preacher [who] was rather verbose, with a marked inclination to philosophizing, was also a prolific writer. He published a series of theological treatises on providence repentance, and similar themes. . .”4

Albelda was active in Valona for ten years, when a pupil of his disrespectfully insisted upon his right to deliver a sermon in one of the city’s four synagogues not occupied at the time by Albelda. Albelda refused the request. The congregation, which admired and esteemed Albelda, referred the contentious matter to R. Abraham de Boton in Salonika. He supported Albelda, recommending (Leḥem Rav, no. 73) that the young man not be permitted to deliver his sermon. Later in Salonika where he was supported by the rabbinate, Albelda provided halakhic leniencies on the prohibitions of issur ve-heter (prohibited and permitted foods).5 Albelda’s first books were published posthumously by his sons Judah and Abraham, and, after the death of Abraham, by Judah.

I

Figure 2. Perushim le-Rashi title page 1, 1525

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Our first work is Perushim le-Rashi, that of the elder Moses Albelda as well as R. Aaron Abulrabi (Abu al Rabi), R. Samuel Almosnino, and R. Jacob Canizal, and a small part of a commentary on the Ramban (R. Moses ben Nahman).6 It is a super-commentary on Rashi’s Torah commentary. Comprised of four commentaries, Perushim le-Rashi was published in Constantinople, c. 1525 in folio format (20: 98, 24, 23-73 ff.).

Figure 3. Perushim le-Rashi title page 2, 1525

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

The title-page is simple, merely stating, Perushim le-Rashi. Avraham Yaari informs that there is a variant copy with a different title page with a slightly more extensive text, adding the names of the commentators and noting that it was printed during the reign of Sultan Suleiman, who reigned from 1521 to 1567, as well as a copy that states the place of publication was Constantinople. He also notes some variation in the foliation. However, while adding the names of the commentators, the variant copy lacks both the name of the printer and references to Sultan Suleiman. I. Rivkind also details variants in Perushim le-Rashi, noting the two title-pages reproduced here. He begins his description by describing this work as [Constantinople? 1525?].7

Isaac Yudlov, in his bibliography of the Israel Mehlman Collection in the Jewish National and University Library, also notes that Perushim le-Rashi was printed during the reign of Sultan Suleiman, except that his description of this work varies in several details from the above description. He dates this work to c. 1530 and notes that some of the foliation is in error and that .the fonts vary from contemporary books printed in Constantinople.8

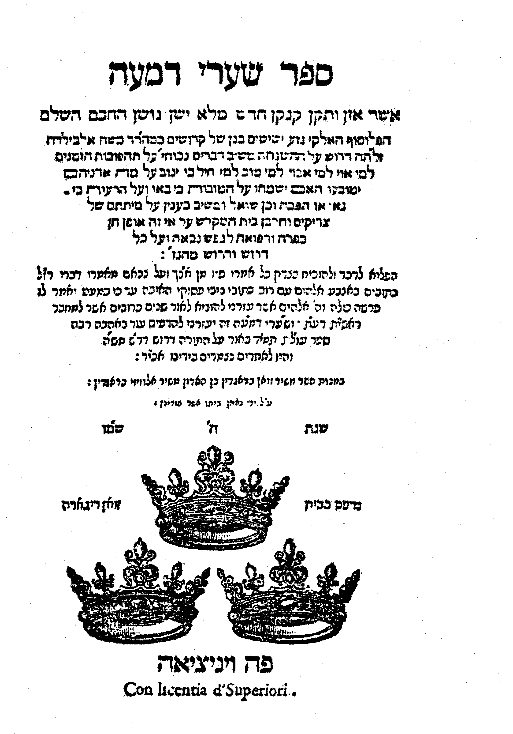

Figure 4. Perushim le-Rashi text, 1525

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

The text begins on the verso of the title page in two columns, the inner the commentary of Canizal, the outer of Almosnino. After parashat No’ah there is an apology from the printer, stating that he did not initially have the commentary of Moses Albelda for Bereshit, but has since obtained it and prints it here. From Lekh Lekha there are three commentaries, Albelda on top, the two others in columns as before. At the end of Lekh Lekha there is a second similar note from the printer adding the commentary of Aaron Abu al Rabi. The format is now Albelda at the top in the outer column, the inner column R. Aaron. Below are Canizal and Almosnino as before. This format is not adhered to throughout, however, for in places the commentaries, while still in two columns, are offered sequentially. Excepting occasional headings and initial words the entire work is set in rabbinic letters. As noted by Yudlov, pagination is neither consistent nor always correct; the colophon simply notes the completion of the work.

Many of the title-pages of Constantinople publications of this period lack both the location and name of the printer. As noted above, based on the fonts and style of the book, Perushim le-Rashi is generally recorded as a tentatively dated c. 1525 and that there are variations in both the text and foliation. In some instances, the commentary of Canizal is longer, suggesting that a more complete manuscript was found and the longer pages substituted. It has also been suggested that it is possible that, in fact, there may be variant issues of Perushim le-Rashi, that is, copies in varying states printed from one setting of type but altered by corrections or additions, but rather two editions resulting from a new setting of type for the book.

II

We turn now to the books of R. Moses ben Jacob Albelda, beginning with the works printed in the sixteenth century; two titles, published posthumously in Venice in the 1580s.

Albelda’s first published title was Reshit Da’at, printed in the year ה"שמג ([5]343 – 1583). Reshit Da’at, ethical discourses on providence and repentance, was printed at the press of Alvise Bragadin in a 20 cm. quarto format (40: 143 ff.). The Bragadin press, founded in 1550, had begun printing with Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah with the glosses of R. Meir ben Isaac Katzenellenbogen (Maharam, 1473-1565) of Padua. Contention over that work with the press of Marco Antonio Giustiniani resulted in the Talmud being burned in 1553 and Hebrew printing ceasing in Venice for approximately a decade. When Hebrew printing resumed in 1563, Bragadin was among the first to again publish Hebrew books. The Bragadin press would continue as one of Venice’s leading Hebrew print-shops, issuing Hebrew titles into the eighteenth century under several generations of Bragadins. James Bloch writes that “the Bragadin press, that is, the house of Bragadini represented the most famous Venetian press of the period.”9

The title, Reshit Da’at, is from “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge (reshit da’at); foolish ones scorn wisdom and discipline” (Proverbs 1:7). The title-page states that it was:

Written by the complete sage, “the son of holy ones” (Pesahim 104a: Avodah Zara 50a) R. Moses Albelda, and in it are novellae and discourses, “New ones, recently arrived” (Deuteronomy: 32:17) in Zion. The introspection of the author “by the benevolence of the hand of God upon him” (Ezra 7:9) on the Torah, on providence, and on repentance. As God has merited us to complete this book, we will print Sha’arei Dimah, also written by the author in completeness on divine providence. . .

Printed by Zoan Bragadin, son of Alvise Bragadin

by Asher Parenzo, the faithful member of his household.

Figure 5. Reshit Da’at text, 1583

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Figure 6. Segol, Reshit Da'at, 1583

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

A three crown pressmark, described by Avraham Yaari as being in the form of an inverted segol, the Hebrew vowel represented by three dots forming an upside down equilateral triangle appears on the title-pages of the books printed by the Bragadin press.. This pressmark, employed by Alvise Bragadin and his son Zoan Bragadin was subsequently used by Zoan (Giovanni) di Gara. It was brought to that press by Asher Parenzo, who also employed it but with an additional single small crown, all evidence of the considerable cooperation (collaboration) between these Venetian presses. The personnel moved easily between them. This pressmark also appears on books printed in Salonika.10 The three crowns are reproduced at the end of the text of Reshit Da’at in a slimmer format.

Figure 7. Reshit Da’at Crowns 2, 1583

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

A considerable amount of prefatory material is followed by the text, set in a single column in rabbinic letters, in six sections each subdivided into varying numbers of chapters, and concluding with indexes. On the last page of Reshit Da’at is the statement Con Licentia De Superiori, representing the right of the state to grant and sanction publication, this despite the fact that ecclesiastic centers had already approved its contents.11 This statement appears most often on the title-page, as is the case in all of Albelda’s following works, but here is on the final page of Reshit Da’at. Avraham Haberman notes that there are numerous copies of Reshit Da’at with variations in the foliation.12

In 1586, Moses ben Jacob Albelda’s second title, Sha’arei Dimah, was published. It is an ethical work, on divine providence, vanity, suffering, and atonement, as well as a commentary on Lamentations. Sha’arei Dimah was printed at the press of Zoan di Gara in octavo format (80: 10, 140 ff). That press, active from 1564 to 1611, printed more than 270 books, primarily in Hebrew letters, and only infrequently in non-Jewish languages. Frequently referred to as Giovanni di Gara, the name Giovanni is derived from Zoan that is Iohannes. The text of the title-page, has the three crown pressmark, addressed above.

Figure 8. Sha’arei Dimah, title page, 1583

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

The title, Sha’arei Dimah, is found in tractate Berakhot 32b, which states:

Rabbi Elazar said: Since the day the Temple was destroyed the gates of prayer were locked, as it is said (referring to the destruction of the Temple) “Though I plead and call out, He shuts out my prayer” (Lamentations 3:8). Yet, despite the gates of prayer being locked the gates of tears (sha’arei dimah) have not been locked as is stated: “Hear my prayer, Lord, and give ear to my pleading, keep not silence at my tears” (Psalms 39:13).

The text of the title-page, which is somewhat lengthier than that of Reshit Da’at, has an initial line that states “give ear and amend ‘there is a new container full of old wine’ (Avot 4:20) old wisdom complete.” The title-page text begins with a reference to Albelda:

the godly philosopher, “the shoot of an ancient line” (Moed Katan 25b) “the son of sacred ones” (Pesahim 104a; Avodah Zarah 50a) R. Moses Albelda, discourses on providence “proper words” (Psalms 24:26) on the vicissitudes of the times “Who cries, “woe! who, Alas!” (Proverbs 23:29); who is good, who is strong “place not vain hope” (Psalms 62:11 ‘. . .”

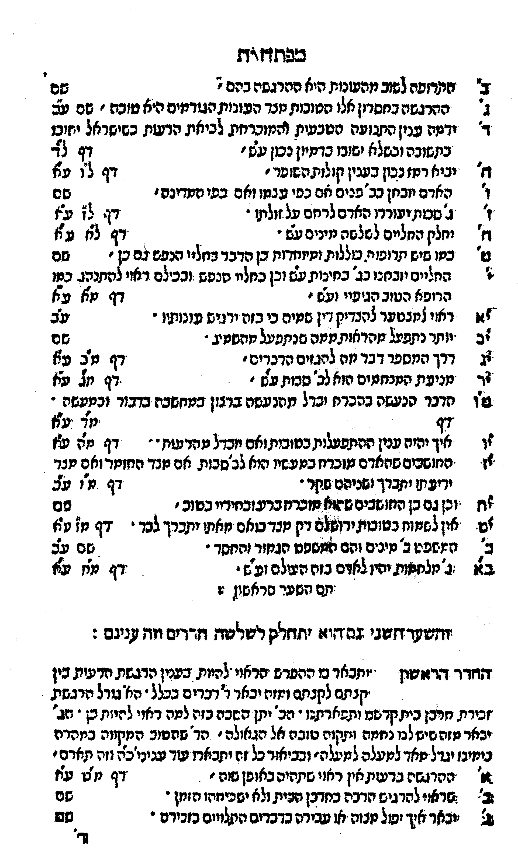

The title-page references Reshit Da’at and references Olat Tamid and Darash Moshe, yet to be published. It is followed on the verso by a brief paragraph from the printer, an introduction, and then a description of Sha’arei Dimah’s contents, several detailed indexes (below), and then the text, set in a single column in rabbinic letters.

Figure 8. Sha’arei Dimah, index, 1583

Courtesy of

Hebrewbooks.org

III

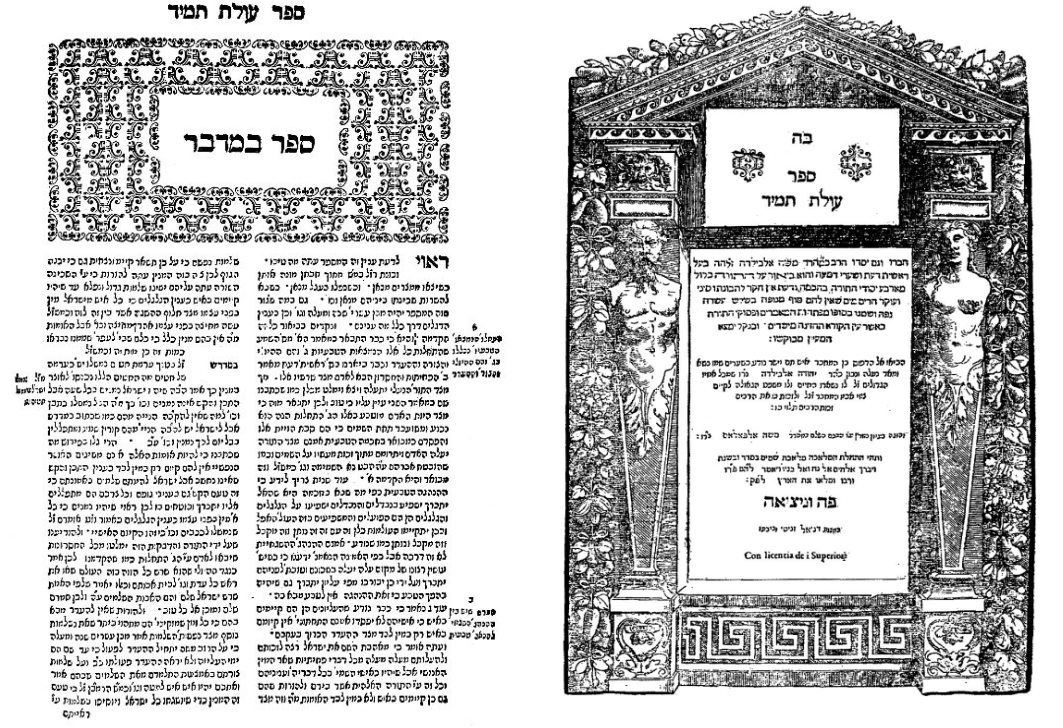

As noted above, two of Moses ben Jacob Albelda’s works, Olat Tamid and Darash Moshe were printed in the seventeenth century. We begin with Olat Tamid, Exegetical discourses on the weekly Torah readings by R. Moses ben Jacob Albelda. Olat Tamid was published posthumously by Albelda’s son Judah at the press of Daniel Zanetti, in folio format (20: 231, [4] ff.). This Zanetti, one of several members of the Zanetti family who printed Hebrew books in Venice, was active from 1596 to 1608, publishing more than sixty titles.13

In contrast to Albelda’s previous works, Olat Tamid’s title page has a frame with busts of an unclad man and a woman at the sides.14 Parenthetically, the title-page frame image, inconsistent with Jewish standards, represents a common practice in Italy at the time. Jews, prohibited from owning presses, published Hebrew books in association with non-Jewish partners. As custom frames were expensive to produce, Jewish printers frequently used the frames of their gentile partners.

Figures 10 and 11. Olat Tamid, 1600

Courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

The title page dates the beginning of the work to the seder and year “And God blessed Noah and his sons, and said to them, be fruitful להם פרו (Heshvan, 361 = September/ October, 1600) and multiply, and fill the land” (Genesis 9:1).15 The text lists Albelda’s earlier works and states that “‘There is no searching of his understanding’ (Isaiah 40:28), Albelda ‘Sinai and uprooter of mountains’ (Berakhot 64a, referring to both the breadth and depth of his learning), ‘water without end’ (Yevamot 121a), ‘sifted with thirteen sieves’ (Menahot 66a, 76b). At the end are indices . . . .” It also informs that Olat Tamid was brought to press by Judah Albelda, who, from all of Moses Albelda’s sons remained alive and had the judgment of redemption to fulfill his father’s directive to merit the public. The colophon dates completion of the work to 29 Marheshvan, erev Shabbat, presumably the same month rather than the following year, which was Monday, November 6, 1601.

The verso of the title page is followed by a brief introduction from Judah Albelda followed by a lengthy introduction from Moses Albelda, who begins by noting that his life has been full of travail. At the conclusion Albelda informs that he has divided his Torah commentary into two parts, Olat Tamid, which is the exegetical discourses, and the more homiletical Darash Moshe. Next is the text, in two columns in rabbinic type, accompanied by brief marginalia. The attention given to biblical books is uneven, it being Genesis (4a-106a), Exodus (106b-169b), Leviticus (170a-184b), Numbers (184b-210a), and Deuteronomy (210b-231a) ending at Vayeleich. The volume concludes with indices.16 After Judah Albelda’s introduction and sections of the book is an attractive tail-piece (below).

Figure 12. Olat Tamid, tail piece, 1600

Courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

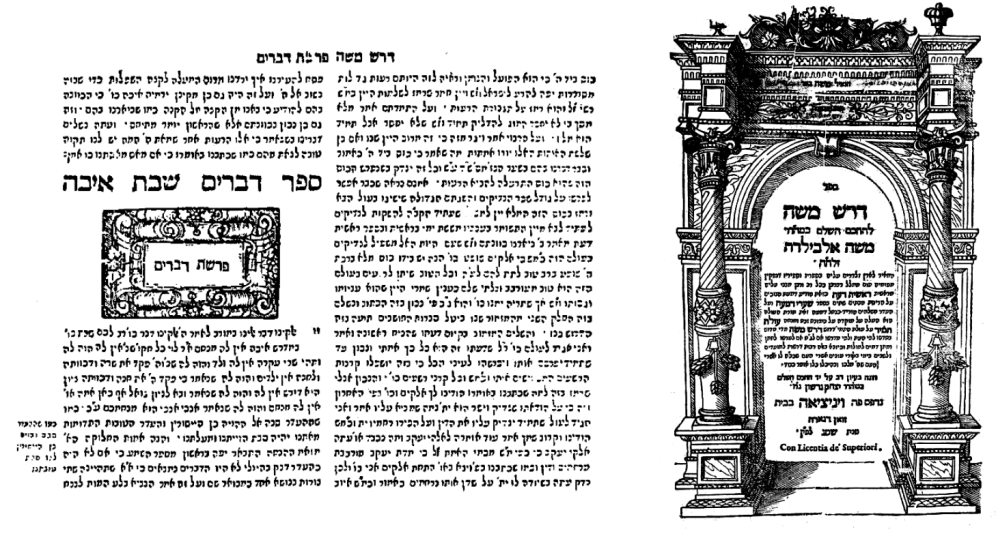

Our next and final title by Moses Albelda is Darash Moshe, homilies on the Torah, festivals, and eulogies, complimenting, as noted above, Olat Tamid. Darash Moshe was printed at the press of Zoan (Giovanni) di Gara in folio format (20: [6], 125 ff.).

The title page refers to Albelda, stating, “who illuminates the earth and those who dwell upon it” (prayer book) with his books and narratives that came forth from his mouth, “a mouth that spoke great things” (Daniel 7:8, 20). It refers to Albelda’s other works, Reshit Da’at, Sha’arei Dimah, and Olat Tamid, concluding that Darash Moshe is based on sermons delivered monthly, according to the circumstance, whether for gemilut hasadim, a groom, milah, similar occasions, or festivals. It further informs that the editor was R. Isaac Gerson.

Figure 12. Darash Moshe, 1602

Courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

The title page is followed by a brief preface by R. Judah Albelda stating that it is the words of the two brothers, the author’s surviving son; his other son, Abraham, who assisted in the publication of the earlier books is now deceased. Next is Moses Albelda’s introduction, in which he informs that he named this book Darash Moshe because it includes his name and it is “‘my mouth that speaks’ (Genesis 45:12), ‘but dust and ashes’ (Genesis 18:27, Job 42:6), for most of my words in this book were spoken at intervals when the heads of the people, ‘more, and more honorable’ (Numbers 22:15) assembled, diligent in their learning.”

Next are several indices and the text, which is set in two columns in rabbinic type and accompanied by marginal references. The text begins with discourses on the weekly Torah readings and includes eulogies, among them one for R. Joseph Caro (d. 13 Tammuz, [5]335 = Tuesday, July 1, 1575), and discourses for the occasions noted on the title page, festivals, Shabbat ha-Gadol, and at the end verses in Proverbs. Darash Moshe concludes with the colophon of Isaac Gerson; he expresses his joy at the completion of this book together with the other books of the author that he worked on. It provides the date that work was completed, Friday, 24 Heshvan, parashat “What man is this האיש הלזה (November 8, 1602 = ([5]363)” (Genesis 24:65, i. e. parashat Hayyei Sarah).

IV

R. Moses Albelda and R. Moses ben Jacob Albelda were scholars who served their respective communities under difficult conditions and hardship. The former enduring the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, the latter facing contentious relationships with members of his communities. Nevertheless, both were men of accomplishment and respected by their peers.

A number of questions can be asked concerning the publication of Moses ben Jacob Albelda’s books. First, why did he publish several books by di Gara, then issue Olat Tamid by Daniel Zanetti, and then return to di Gara to publish Darash Moshe? That question remains unanswered, as both presses were highly regarded. Secondly, why did his sons print Moses ben Jacob Albelda’s books in Venice when Salonika, where Albelda had served as rabbi, had presses of repute. I would suggest that Albelda’s sons, and this is highly speculative, perchance might have become resident in Venice. That city had diverse Jewish communities, including Jewish merchants from Salonika who had taken up residence in Venice. Perhaps Albelda’s sons, again, this is speculative, may have been among those who relocated. Of greater importance is that Albelda’s books were printed in Venice.

Unfortunately, Albelda’s books, existing in single editions only, have not been reprinted excepting as facsimile editions available at Amazon. That both R. Moses Albelda and R. Moses ben Jacob Albelda are not well remembered today fits a pattern, as noted earlier, of rabbis and sages of repute who served their communities and wrote books of value, but whose memories have faded with time.

1 I would, once again, like to thank Eli Genauer for his observations and comments.

2 Additional articles describing eminent rabbis and sages not well remembered today appearing in Sephardic Horizons are “Moses ben Baruch Almosnino: A Sixteenth Century Multi-Faceted Sephardic Sage in Salonika.” (Sephardic Horizons, 11: 4, Fall, 2021); “Jacob Judah (Aryeh) de Leão Templo: A Converso Scholar, a Jewish Hahkam” (Sephardic Horizons, 12:1, Spring 2022); and “Solomon de Oliveyra: A seventeenth Century Sephardic Sage” (Sephardic Horizons, forthcoming).

3 Shimon Vanunu, Rabanan taḳife arʻa : toldot rabotenu shebe-Śaloniḳi ṿe-Yaṿan (Jerusalem, 2020), p. 686 [Hebrew].

4 Meyer Kayserling, “Albelda (formerly Albeilda)” and “Albelda, Moses ben Jacob” Jewish Encyclopedia v. 1 pp. 322-23; Vanunu, p. 687; Moritz Steinschneider, Catalogus Liborium Hebraeorum in Bibliotheca Bodleiana (Berlin, 1852-60), col. 1768 n. 6427.

5 Vanunu, p. 687.

6 R. Aaron Abulrabi (Abu al Rabi, c.1376- c.1430) was a Sicilian of Spanish origin, a well-traveled person of diverse interests, knowledgeable in Kabbalah, astronomy, and philosophy, a grammarian, and biblical commentator. His commentary, somewhat polemical, refuting Karaite, Muslim, and Christian biblical interpretations, is his only extant work. R. Samuel Almosnino (d. 1551) served as rabbi in Salonika in the sixteenth century. In addition to the commentary he was also the author of a commentary on the minor prophets, included in the large Bible printed by R. Moses Frankfurter (Amsterdam, 1724-27). R. Jacob Canizal most likely from the fifteenth century, is best known for the commentary printed here. Perushim le-Rashi is often referred to as Sefer Canizal.

7 Avraham Yaari, Hebrew Printing at Constantinople (Jerusalem, 1967), p. 86 n. 101 [Hebrew].

8 I. Rivkind, “Variants in Old Books,“ in Alexander Marx Jubilee Volume Hebrew Section (New York, 1950); Isaac Yudlov, Ginzei Yisrael, The Israel Mehlman Collection in the Jewish National and University Library (Jerusalem, 1984), pp. 108-09 n. 633 [Hebrew].

9 James Bloch, “Venetian Printers of Hebrew Books,” in Hebrew Printing and Bibliography” by Charles Berlin (New York, 1976), p. 22.

10 Bloch, p. 84; Avraham Yaari, Hebrew Printers' Marks: From the Beginning of Hebrew printing to the End of the 19th Century, (Jerusalem, 1943, reprinted Westmead, Farnborough, England, 1971), pp. 12, 131 no. 18 [Hebrew].

11 Bloch, p. 85.

12 A. M. Habermann,Giovanni Di Gara: Printer, Venice 1564-1610. ed. Y. Yudlov (Jerusalem, 1982), pp. 27-28 no. 64 [Hebrew].

13 Meir Benayahu, “The Books Printed in Venice at the Zanetti Press,” Asufot XII pp. 9-17 [Hebrew].

14 Concerning the usage of such frames see Marvin J. Heller, “Mars and Minerva on the Hebrew Title Page,” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 98:3 (New York, N. Y., 2004), pp. 269-92, reprinted in Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book. Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2008, pp. 1-17.

15 The verse appears to contain a typographical error, for where it says “blessed Noah and his sons” both instances of the word את were set as אל. Other possible inferences are not addressed here.

16 Meir Benayahu, “Zanetti Press,” Asufot, pp. 101-04 [Hebrew]