Hélène Jawhara Piñer

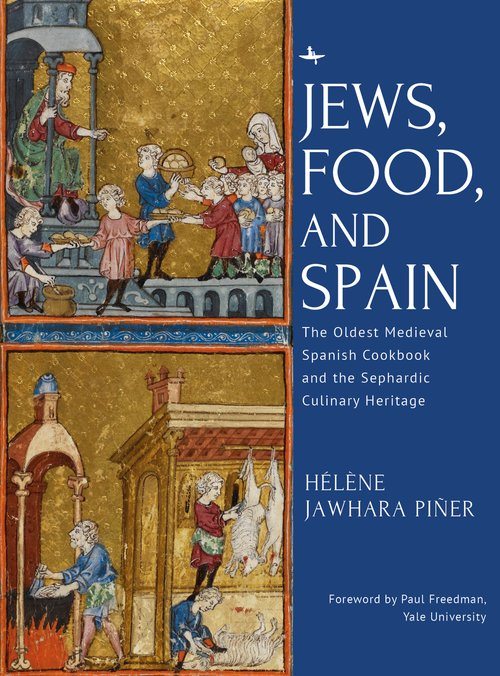

JEWS, FOOD, AND SPAIN: THE OLDEST MEDIEVAL SPANISH COOKBOOK AND THE SEPHARDIC CULINARY HERITAGE

Brookline, MA: Academic Studies Press, 2022. ISBN: 978-1644699188

Reviewed by Regina Igel1

In this book’s Foreword, Professor Paul Freedman, from Yale University, states that many of the Iberian Jewish culinary ways were described in the accusations against the conversos who kept the practice of their Judaic faith in hiding. Being discovered, either by neighbors denouncing these practices or by a vigilante group sent out by the Church, the denunciations were based mostly on habits derived of food preparation; on Fridays, the New-Christians would cook enough to be fed all Saturday, when it is forbidden by the Jewish religion to cook. The dishes served, such as eggplant and meatballs, among so many others, were reminiscent of the times before the Inquisition, which lasted from 1438-1834. The recipes were rather passed by word of mouth (no pun intended).

Freedman refers to Dr. Piñer as a pioneer in her discoveries related to a book of recipes composed presumably by a Jewish person living in Iberian lands in the thirteenth century. Written in Arabic, described by Freedman as a ‘lingua franca’ in al-Andalus while Hebrew was the language solely for religious ceremonies, it contains 462 recipes. Its title is Kitab al-tabih, or “the book of cooking,” according to Prof. Freedman; its author is unknown. Furthermore, he observes that, because of the Islamic chiefs in power, Jewish recipes were not openly placed in the book, except for a few descriptions exposing their origins, such as “A Jewish Dish of Eggplant Stuffed with Meat” and “Stuffed, Buried Jewish Dish.” All other recipes show some allusions to a possible Jewish component, as it could be found “through sixty-nine meatball recipes or a recipe for mock hare using eggplant” (p. x), since hare, according to Jewish dietary laws, isn’t allowed to be consumed by observant Jews.

In her intense and fruitful research, Dr. Piñer describes how foods consumed by the Jews were avoided by the non-Jews. They were afraid that the use of cilantro, for example, a staple in Jewish tables around medieval times, might mislead neighbors and others to think that they were Jews. It was appropriately replaced by parsley. The Foreword gives readers a very good orientation to the book’s main topic, the tripod comprising food, religion and language, by which the Sephardim and their cultural legacy are identified. Dr. Piñer unravels many of the recipes included in the book Kitab al-tabih, revealing their Jewish roots and influences, from medieval to modern times.

Stepping out of the very good elucidation provided by Prof. Freedman, readers continue with the “Introduction,” a text signed by Dr. Piñer. Here, she presents the purpose of the book, that is to offer “an analysis of a variety of Jewish food – Sephardic – that existed in Spain at the end of the Middle Ages by way of a reading of the Kitab al-tabih” (p. 1). She further clarifies that:

This volume is neither a history of the Sephardic Jews of Spain … nor is it an exhaustive study of all the sources that trace the history of the Iberian Jews, be they literary, judicial, notarial, and so on. Rather, this book is an examination of food and cuisine in the light of those texts that address the history of Jews in medieval Spain, principally the first cookbook that covers all periods and territories: the Kitab al-tabih” (p. 1).

After explaining the methodology applied to the book and the sources on which it is based, the author discloses the “critical bibliography” along with a plethora of footnotes to the many book titles regarding the history of the Sephardim, their relations with the Muslims in the Hispanic territory, and especially medieval food and related cookbooks, as analyzed by modern historians. The “Structure of the Book” is the last part of this Introduction, leading readers to what to expect in the remaining almost three hundred pages.

The book comprises three parts: Part One – The Jews’ Place in the Constructions of an Andalusian Cuisine (Twelfth to Fourteenth Centuries). This section refers to the intriguing composition of the Kitab al-tabih, that does not disclose the religion nor the ethnicity of its author. Dr. Piñer, however, has found enough indication that whoever wrote that book, “was neither Christian nor Berber and knew about medicine and Jewish dietary laws” (p. 13). Part One comprises several chapters and subdivisions. Chapter 1 relates mostly to the revival of interest towards the history of medieval food; the coexistence of Jews and Muslims from the ninth to the twelfth centuries and the religious coexistence and conversion on the Iberian Peninsula of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Chapter 2 is akin to discover “The Jewish Stamp in the Kitab al-tabih.” It also is divided into sections, starting with the reply to the interesting question: “What is meant by ‘Jewish Cuisine’?” Also discussed is the compelling topic of the identity of the book`s author, as posed by the question: “Written by an anonymous Jewish author?” (p. 67). Chapter 3, “Jewish and Muslim Food Consumption and Cooking Practices in the Kitab al-tabih,” informs about the differences between these two groups, based in religious practices. Chapter 4 brings readers “Eggplant: The Jewishness Marker,” a brief but profound entrance to the hidden and not so hidden clues regarding prohibited nourishment, when eggplant would be used instead of hare in the dish (rabbit was also not allowed to be consumed by Jews, though the Muslims had no restriction towards these animals).

Part Two, “The Legacy of the Multicultural Cuisine of Al-Andalus (Fourteenth to Seventeenth Century): The Evolution and Perception of Jewish Food” comprises Chapters 5 to 8, one of which reveals the many literary productions by Jews living in several Spanish regions under the cover of Christianity. Chapter 7, comprising tables where several cooking books or recipe books issued in medieval centuries are listed and refers to food as an identity marker. The following chapter refers to the Inquisition and their method of registering the eating habits of Jews, thus leading to a religious identification; as mentioned earlier, the inquisitors were in charge of denouncing Jewish practices of the new-Christians or conversos. Therefore, they brought documents about food and culinary practices into details that would feed the priests’ hunger and thirst for torturing the people they mistrusted as good Christians.

Part Three, “Sephardic Jewish Culinary Heritage: Between Rebirth and the Desire to Recognize a Past Legacy,” comprises Chapters 9 to 12. In Chapter 9, Dr. Piñer observes that “The lack of knowledge and recognition of the Spanish Sephardic culinary legacy within Spain’s current food culture is highly problematic” (p. 187). She proceeds to list the dishes which were described by the Inquisition priests and called a dish the Jews prepared on the eve of Saturday in their hateful lines, thus, uncovering their real religion under the disguise of ‘conversos’ that are current among Sephardim today, such as adafina, then known as ‘Ani.’ Many other dishes are mentioned that are still prepared and consumed by Sephardic people today wherever they might be living. Chapter 10 fluently indicates several other dishes typical of the Sephardim, while “Recipes and photos of Jewish dishes from the Kitab al-tabih” along with clear and colorful pictures of some dishes are the topic of Chapter 11. The last numbered Chapter (12) contains “Recipes and Photos of Iberian medieval dishes in the Sephardic Culinary Heritage of the Mediterranean Basin,” as translated and adapted to our days. At the concluding remarks, Dr. Piñer observes the international level of today’s Sephardic cuisine, with restaurants and chefs specializing in the traditional recipes adapted to modern times in Israel, the United States, and elsewhere.

This book is to be kept among the treasured books that many readers have in their homes, both for consultation and for the delight of learning the history of Sephardim through the food that they consumed in medieval times. Though Kitab al-tabih isn’t a book of Jewish recipes, the wit of Dr. Hélène Jawhara Piñer, a specialist in the multicultural medieval culinary history of Spain, focuses on Jewish culinary heritage. The vast bibliography inserted in this volume and the long index of topics testify to the richness found in this very instructive and useful book for historians, students, and curious people, in general, and also, chefs.

1 Regina Igel is Professor Emerita of Spanish and Portuguese at the University of Maryland, College Park, MD.