Leaving Mashhad and Iran : An Iranian Jew Speaks of his Family’s Experience

David Livi is Interviewed by Judith Roumani1

transcribed by Gila (Martha) Griner

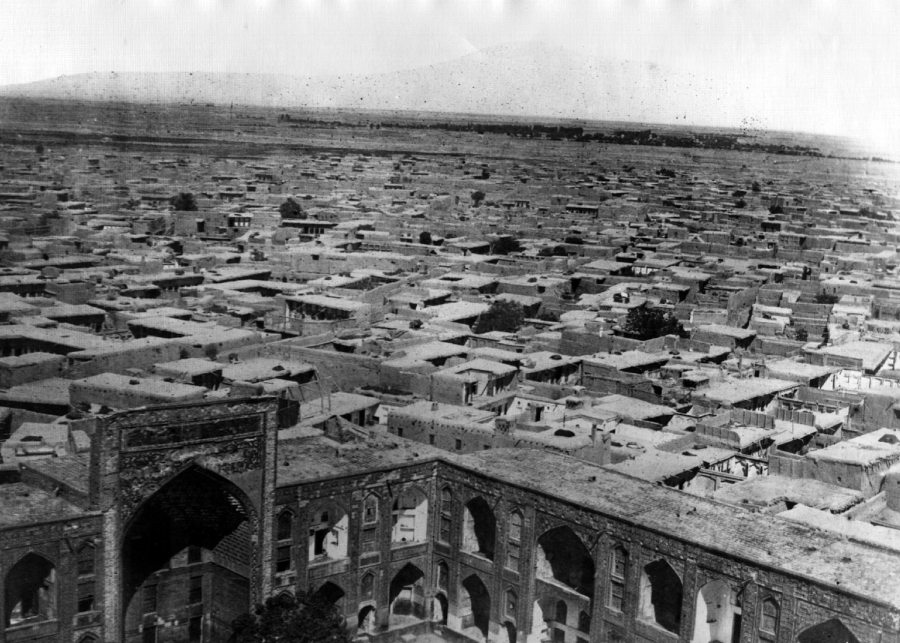

Mashhad in 1858, Mirza Ja'afar Mahrassah - Giannozzi

JR: This is Judith Roumani on April 20, 2023.

I am currently in Italy and today I visited the ruins of Pompei. I have learned (not from our guide, who was confident that there were no Jews in Pompei) that Jews even lived as slaves or as traders in ancient Pompei until the volcanic eruption that destroyed the city. Here is a story of Jewish survival from, of all places, modern Iran. I am about to interview an Iranian Jew, David Livi, who has lived in America for many years, and is going to tell our readers about his experiences in Iran, living in Iran and in America.

I appreciate this very much and it's a great privilege to interview you, David Livi.

JR: Would you like to tell us, first of all, how do you feel about Iran today, as someone who left many years ago?

DL: One Israeli president, I think, I am not sure exactly, a president, I think, mentioned something that is very interesting and very accurate to me, that: "I feel my mother is Iran and my father is Israel": that is the feeling.

JR: Oh, that is an interesting way to put it. Yes.

DL: To begin, I just want to tell you a little story about our community and our family.

JR: Thank you, that is perfect.

DL: We are coming from the North-East of Iran, a town called Mashhad, and in approximately 1820, right before Passover, the Muslims, as it was a religious town, came to our neighborhood and they started to massacre Jews over there.

JR: Terrible.

DL: Over thirty people. The day after, the rabbanim at the time, they mentioned that the only way we can survive is to convert to Muslims. So, our community, all of them, went and converted to Islam and they practiced outwardly for close to a hundred years.

JR: Wow, that's amazing.

DL: They were Muslims but at home, everybody was kosher, everybody was praying, they had a little shul in every section, there was like a Jewish ghetto and in the ghetto they had schools hidden in the basements that they used to pray and they kept going for a hundred years.

JR: That's amazing, such amazing emunah.

DL: Around 1920, after the government changed and the father of the king (the shah) came to power, they gave the Jews freedom to come out. So, slowly, slowly they came out, they could live in the town, so they lived in the town slowly. They came back to the center of the country and to the capital.

JR: So, they moved mostly to Tehran.

I.M.: Yes, Tehran.

JR: Because they felt safer there?

DL: Yes, safer and it is more freedom. Of course, it took a while because they had their freedom from the 1920s to the 1950s. They had more and more freedom over there, but I remember, even I remember, in the street, walking in the street, sometimes people insulted us: “That's a Jew!” and calling us names and stuff. In Tehran we never had that problem anymore.

So, the community, from 1940 or 1945, started to move to Tehran, and by the late 1950s or early 60s almost nobody was left over there [in Mashhad], everybody came to Tehran.

Because we were one community, we were always very attached to each other. We had intermarriages between the families in the community, and [there were] very few marriages out of the community.

JR: So, your community stayed a separate community within the Jewish community?

DL: Yes, within the Jewish community. One of the main reasons was, the community was a nice size. There were enough boys and girls that they could meet each other. Since we knew the parents, we knew exactly what family we could choose from. What was right for our family, within our family.

It was much easier to get out too and meet other girls, other boys in other communities, we were very close to each other. So they mainly married inside the community, maybe 90%, 95%.

JR: Your community in Mashhad had always remained Jewish, [there was] no intermarriage with Muslims?

DL: Never. Only, maybe by force. They had to give away one or two daughters. They had forced them, they did it. Otherwise, every kid that was born, every girl, they used to be named after one of the boys in the family. For instance, my dad and my mother are first cousins too.

JR: Oh, I see….

DL: When they were born, they [were] named after someone and when somebody wanted to get married they asked for a daughter that had already been engaged to somebody. I am sorry, I don't have excuses.

JR: Oh, I see, yes. All kinds of subterfuges to remain Jewish. It was very courageous.

DL: Yes.

JR: How did they manage with food? How did they manage to keep kashrut?

DL: Outside, they pretended to be Muslims. So they bought not-kosher meat, not-kosher food, and threw it away when they got home, and added on the rabbi’s shehita that they used to slaughter cows.

They taught the rabbis at the time, they taught a lot of young people how to kill chickens, so they kept it kosher.

JR: What about working on Shabbat? How did they manage with that?

DL: I know about my family, my grandpa….

On Shabbat, my father used to tell me that [when] he was a young man, around six, seven years old, my grandpa used to go to shul, opened the shop and asked my father to sit in front of the shop and whoever wants to come and buy some food, it was a food shop, the shopkeeper was telling everybody that my grandfather went to the market to bring some food, please come back tomorrow or something, so he turned everybody away, and the next day they started working.

JR: Ok, thank you, this is fascinating.

DL: At that time, all the Jews because they were pretending to be Muslims, were pretending [to observe] all their holidays too, you know. There were a lot of ceremonies, a lot of painting that they do to remember all their history of Mohammed and Ali. All the ceremonies that the Muslims used to do were done outside. Nobody could [was allowed to] really feel that they were Jews [except] at home. To the point that they used to go to the mosque and they prayed at the mosque too. My grandpa, because he had a very good voice, used to pray for the Muslims at the mosque, and come home and pray for the Jews at the synagogue.

JR: Oh my goodness, amazing.

When they got to Tehran, and they could live openly as Jews, did you feel there was any discrimination against people who came from Mashhad?

DL: Almost nada, nada. They were accepted very well, especially in the market. The Jews, not only from Mashhad, from other places too. They had a very good name, having been straight, honest businessmen. They always preferred to sell to the Jews than selling to the Muslims, because they knew the money was safe.

JR: Interesting.

I think I told you that we lived in Tehran in the early 1970s, for a couple of years, and we used to go sometimes to the Mashhadi Synagogue. My husband liked it a lot.

DL: Which one? The one in the Center?

JR: In Tehran.

DL: Because we had like six, seven minyans, Bete Kenesset.

JR: Oh, I see.

DL: But the main building was like a three, or four story building and the second or third floor was the Bet Kenesset.

JR: Yes, I remember, you had to go upstairs, several flights upstairs.

DL: That was the Main Central Synagogue.

JR: Yes, yes!

I have the feeling, the memory, that Mashhadi Jews were more observant than others.

DL: Yes, they are more observant. Thank G-d they had very good rabbis, very good leaders, devoted leaders, without charging any money, any salary, they were serving the community. They did really a great job.

JR: Then, when [did] the Mashhadi Jews leave Iran?

DL: You know because they did not want to send their kids to the army and it was mandatory. A lot of parents when their sons they became fifteen and a half, right before sixteen years of age, they sent them overseas. The majority to the US, the majority to New York.

JR: Oh, I see.

DL: When we left back in 1978, 1979, it was very easy to just join our children in New York and settle down over there. At the beginning we settled down in Queens, in the neighborhood Kew Gardens, and we built a shul over there. Later on, when financially things got better a little bit, slowly then we already moved to Long Island. Almost everybody lives in Great Neck up to today.

JR: I see. Even today they are a coherent community that sticks together and you ….

DL: Yes, we stick together. But marriages outside the [Mashhadi Jewish] community are a little bit more, maybe 30%, 25%, with other Iranians, or with other communities, Americans or outside marriages.

But from the beginning they made laws [rules] that if somebody married a non-Jew, they were rejected out of the community, they don’t accept them anymore. Full force over the young people, forget it about marrying non-Jews. Thanks G-d, besides the one or two boys or girls that are married outside, almost nobody is married outside. As long they are Jews.

JR: Yes, Ok. Thank you very, very much.

Maybe we will continue if you think of things that you’d like to tell us later. Really, I appreciate this very much. We are very honored to be able to interview someone from the Mashhadi Iranian community. Thank you and I wish you a wonderful day.

DL: Thank you, you too.

1 Judith Roumani is the editor of Sephardic Horizons.