Living and Walking the Seam of Jerusalem

by Michael Sager1

The Project

In the final year of my MFA photography program at the Belfast School of Art, University of Ulster, Belfast, Northern Ireland, I took on a project to walk and document the Seam of Jerusalem. The Seam is the area around what was the Armistice line between Israel and Jordan, a division that lasted from 1949 to 1967. This is popularly known as the Green Line. This essay is based on text and images from this ongoing project. A fuller version, in the form of an online photobook, is located at tinyurl.com/TheSeamBook. A video documenting the project can be seen at tinyurl.com/TheSeamProject.

Relics and Ghosts

My home is in Jerusalem. Relics from more than 3,000 years of history have been found below my building. I am fascinated by the idea that where I live has been occupied by people for all this time. I feel the presence of their ghosts as I go about my 21st century daily business.

I live on what is called the Seam, an artefact of more recent history. The Seam is the visible evidence of Jerusalem’s violent division in 1948 and re-unification in 1967. It exists as a slice carved out of the city’s heart.

I leave my home, walk a few metres, and see two adjacent communities with different economies, legal systems and infrastructures. The Seam is the in-between space that both separates and joins the two communities. Like the seam of a garment, the Seam of Jerusalem roughly and visibly connects the two communities.

For three years I, sometimes with my friend Bruce, walked the Seam with cameras and notebooks. We explored the curving thirty kilometres strip through the city. It varies from a few metres to two kilometres wide. This is part of the story of my exploration of the Seam.

The Valley of the Ghosts

At its south-west exit from Jerusalem, the Seam follows Emek Rephaim, the Valley of the Rephaim (עמק רפאים ). The Rephaim of this valley, mentioned in the Christian and Hebrew bibles, are translated variously as ghosts, spirits of the dead, giants, and the terrible ones. Appropriate denizens of the Seam.

The valley runs from Jerusalem to the sea and was used to construct the Jaffa-Jerusalem railway in 1892. The project was headed by Joseph Navon, an Ottoman Sephardic-Jewish entrepreneur from Jerusalem and ancestor of the well-known president of Israel, Yitzchak Navon. In 1949 parts of the line were controlled by the Jordanian Army. Under the Armistice agreement the railway was returned to Israel but suffered numerous terrorist attacks until 1967. It was a single-track line with a winding, slow, and beautiful ride through the forest and hills. Now it is closed, replaced by a high-speed line that takes a faster but much less scenic route.

Removing the Green Line barriers in 1967 provided opportunities in the south-east and the north-west of the city for the newly expanded municipality of Jerusalem to build new housing. These areas were technically over the Seam, but their development was not, at that time, very controversial. Existing Arab neighborhoods were not threatened, although their expansion was often limited because of the new building.

Freeway Bridge, 2021

There are about 200,000 residents, mainly Israeli Jewish, living in these now well-established Jerusalem neighborhoods east of the Seam. This has created an anomaly. Some of those living across the Seam line are Israeli citizens. Some, because they are Palestinians born there, only have a right of residency. They do have the right to apply for full Israeli citizenship. Israel does not make it easy. It is always suspicious about applicants’ true allegiances. And because a major goal of the Palestinian national movements is that East Jerusalem be the capital of Palestine, those that apply are seen as collaborators, even traitors, by their people.

Beit Safafa

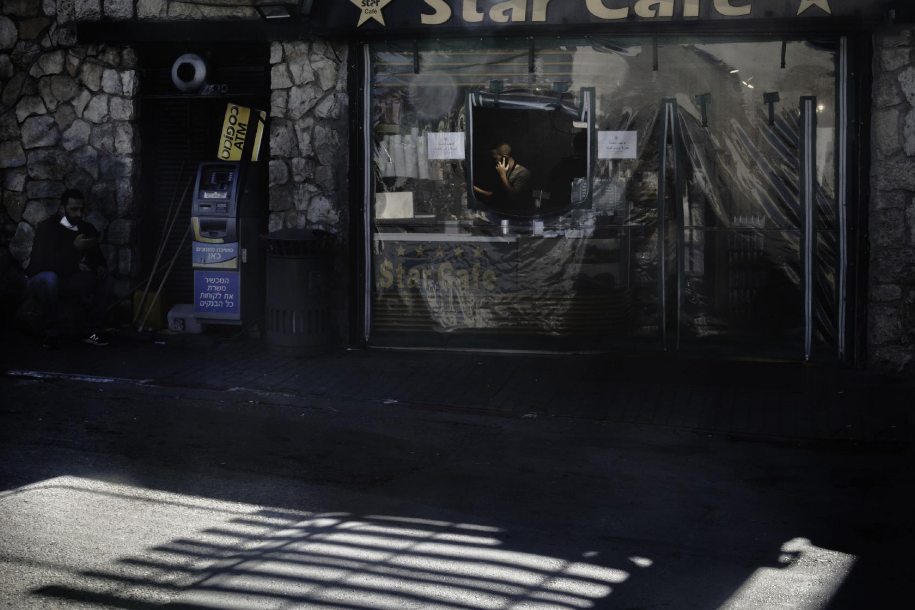

The Star Café is located at the edge of the Arab village of Beit Safafa (بيت صفافا) on the Green Line and services the adjacent light industrial and shopping district of Jerusalem. The cafe offers excellent lattes, good fresh sandwiches, and friendly service.

Star Cafe, 2019 - Beit Safafa

Beit Safafa is Arab, Muslim with a few Christians. Since 1948 its relationship with Israel has been very complicated. In 1948 the Jaffa-Jerusalem railway line became a no-man’s land within the village. Subsequently the cease-fire line was readjusted to divide the village, with the railway area and nearby houses going to Israel and the majority eastern part of the village going to Jordan.

The Seam on the Arab side of the railway has some remains of concrete fortifications in fields that are now used for grazing sheep and goats. We talked to one of the shepherds, a field’s owner. He said the city will not approve housing development on these fields. He does not know why. It is prime real estate – he could become a millionaire if it did.

This Arab village is considered to be ‘friendly’, a distinction that seems strange to outsiders but makes perfect sense to Israelis. Beit Safafa has a school that teaches integrated classes of Arab and Israeli kids using both Arabic and Hebrew. We encountered the two imams of the village strolling companionably in the morning sunshine, we discussed our religions, and agreed that Judaism and Islam are brothers. We were invited any time to attend their classes at the village mosque.

We talked to Arab locals on the original Israeli side of the Seam. They explained how strange it is that they have full rights as Israeli citizens but their family members and friends in the same village, 200 metres away across the railway line, have only Jerusalem ID cards and residency: but no automatic Israeli citizenship. We could only agree.

Giv’at HaMatos

Giv'at HaMatos (גבעת המטוס) ‘Airplane Heights’, is a high area to the west of Kibbutz Ramat Rahel and to the east of the Arab village of Beit Safafa. From 1948 to 1967 it was occupied and fortified by Jordan because of its commanding view over central Jerusalem. In the immediate years following 1967 it remained neglected. It was a bleak, windswept hill with mine fields and derelict fortifications.

From 1991 it slowly turned into a shanty town. The government built ‘caravans’ (Israeli terminology for prefabricated buildings) to house Ethiopian Jews airlifted to Israel. It also placed homeless families, often Russian immigrants, in these caravans.

Immigrant Housing. 2020 - Ramat Rahel

Now the city wants to develop the hill and rehouse local families. It has announced plans to build a new neighborhood with hundreds of homes, shops, public buildings, parks, promenades. Some housing will be for Israelis. Some housing will be for the inhabitants of the nearby Arab village of Beit Safafa, whose growth has been limited in all directions. The land is over the Green Line, so there are many international institutions angry with the plans. They claim development on Giv’at HaMatos to be illegal.

I visited the area on a winter’s day of golden light. There was a Bedouin shepherd with his sheep - a scene from the Tanach. In this golden light even the garbage was beautiful.

Jabel Mukaber

After the Six Day War the inhabitants of Jabel Mukaber (جبل مكبر), an Arab village at the eastern extremity of the Seam found themselves living under Israeli rule. They had local voting and residency rights but no automatic rights as Israeli citizens. The village has grown extensively since, with infrastructure poor compared to its adjacent West Jerusalem neighborhoods. Garbage spills over from dumpsters, there are no playgrounds or green areas, there is a shortage of classrooms and kindergartens, and it has only one high school for boys. But not everyone living there, it seems, is poor. I once had to stop my car just outside Jabel Mukaber to allow a fleet of three new black Mercedes saloons to enter it.

Jabel Mukaber is notorious to Israelis as a source of terrorist attacks. Since 2014 there have been four deadly attacks by residents of this village. 15 Israelis died from these attacks. There is a Border Police station at the village’s entrance to West Jerusalem. At times of crisis, they occupy the checkpoint and block the village’s main road.

I live in West Jerusalem in a new housing complex. One day I caught a taxi and gave the driver my address. He said he knew the street, he used to live there. His family were expelled from Morocco and lived there with immigrants from Iraq, Iran and Kurdistan in temporary housing on the very edge of the Green Line: a whole family in a few square metres. He and his brothers became success stories, starting and managing large businesses. Now there are no relics, only memories. Children play soccer and ride their bikes where his home used to be.

Jabel Mukaber and our complex are about three kilometres apart. There is a UN peacekeeping mission headquarters midway between us - perhaps more a symbolic gesture than a practical one. The UN compound is guarded by 4-metre-high walls topped by barbed wire and security cameras. Neither we nor Jabel Mukaber seem to feel the need for such protections.

Blocks with Red X, 2021 - Jabel Mukaber

Military concrete blocks are found all over East Jerusalem and the West Bank. Some sit at the side of a road in Jabel Mukaber. These blocks are now just part of the village scenery. It is unclear when they were last used to block their road. Or why they have a red X, with its paint dripping like blood. Maybe they are future relics warning passers-by of bloody possibilities.

The Peace Forest

The Peace Forest is an artefact of the old ceasefire zones that evolved into the Seam lines. It is a two-kilometre square area south of the Old City. From 1948 to 1967 it was a neutral zone separating the Jordanian and Israeli armies. The area was abandoned and unused. Theoretically it was administered by the UN whose mission headquarters is in the middle of the zone. Anyone that entered this zone during these years risked death.

The zone was annexed by Israel in 1967, named perhaps ironically the Peace Forest, and developed as a recreational area for the Arab and Israeli communities nearby. More trees were planted. An ecological farm and a playground for children were built. The city introduced picnic tables and an outdoor amphitheatre. Strange buildings appeared: a pyramid, a mediaeval tower. I used to think these buildings were relics of military fortifications. When I checked I found they were works of art: sculptured buildings with symbolic significance. I live just over a ridge, to the south of the Peace Forest. The Peace Forest occupies a valley on the other side of the ridge. I am the only person I know that has walked the whole distance of the Peace Forest, from its top to its bottom and back. A walk of one and a half kilometres and a height difference of 250 metres.

At the bottom is a semi-rural Arab village, with sheep, goats, chickens, and donkeys. The walk is rather sad - the park here is neglected and little used. Sometimes Arab families have barbecues. Few Israelis are interested in the short but steep climb down to use the picnic facilities. The Arab village of Jabel Mukaber adjoins the forest to the east, with some houses built (presumably illegally) at its edge.

Man with motorbike, 2020 - Peace Forest

We met a man living on the edge of the Peace Forest who chatted to us, proud of his motor bike. Another local man hospitably brewed us strong black sweet coffee but did not allow us to photograph him or his house – presumably because it was illegally built.

The major feature of the Peace Forest is its garbage. Plastic and cans from picnics, abandoned domestic equipment, used building materials. The ghosts of the old conflicts remain malign.

Abu Tor

Between 1948 and 1967 the Armistice line passed along the centre of Assael Street, a dead-end, 300-metre-long street in the neighborhood of Abu Tor (أبو طور אבו תור). This is usually translated as ‘Father of the Bull’. Along this street was a fence separating Jordanian and Israeli soldiers. Many Israelis on the west side were new immigrants who had fled from Morocco and Iran when the Muslim countries exiled their Jewish citizens. They faced the Arab residents on the east side, who were then Jordanian. The residents of both sides lived in the most remote and neglected boundaries of their respective worlds. Both populations were united and isolated in poverty.

At times disputes between the sides were debated at the UN, such as when an Israeli started to extend his bathroom. In these moments Assael street became the centre of the world.

Abu Tor is the only Jerusalem neighborhood considered bi-ethnic. Which does not mean mixed. Assael Street has been upgraded. Arab style houses on the Israeli side have been bought by the middle class and proudly restored. Gardens are full of jasmine and bougainvillea.

Buying Bread -2021, Abu Tor

The majority Arab side is less developed. It has readable signs that show the Seam. One sign is the language of the graffiti, some supporting Hamas. Another sign is that Israeli houses usually have white solar heating tanks, but Arab houses have black water storage ones. Arab houses sprout satellite dishes. Also, look at the road surface. It usually deteriorates as you cross the invisible border.

Silwan

The East Jerusalem village of Silwan has become a ‘cause celebre’ for liberal Israeli and international organisations. They have publicized its problems world-wide, promoted some extraordinary art works, and supported community groups.

Next to Silwan is an archaeological park called the City of David managed by a controversial Israeli / international organisation called Elad. It uses digs and reconstructions to argue that the original capital city of the biblical King David was not in the Old City but outside the present walls to the south. The site is separated by fences and gates and looks across to the eastern side of a valley over which Silwan has grown.

Silwan Village, 2021

Up to 1938 Yemenite Jews lived in Silwan but in that year were evacuated by the British Mandate Government. This history has been used by Elad to increase Jewish presence in East Jerusalem. It uses political influence, money and the law to acquire houses with Arab residents and move them out, expand the archaeological park, and provide housing for Jews.

I have walked Silwan many times. Alone and with advocacy groups from both sides. My abiding memory is eating my lunch banana as an armed Israeli patrol marched past briskly. They were not interested in responding to my questions.

The Old City

In 1948 Jordan attacked and occupied the Old City of Jerusalem. Jordan expelled the Old City’s Jews and devastated the Jewish Quarter. It continued to be under Jordanian control until 1967. The Seam runs outside the Old City wall, to the south-east, south, and south-west. It is a narrow zone on the outside of the wall.

In 1948 the Zion Gate, a southern entrance to the Old City, saw fighting. Bullet holes remain on the outside of the wall next to the gate, remembering an attempt by the Israeli army to enter the Old City through this gate. The army’s abandoned armored bus remained in this no-man’s land until its removal in 1967.

The Seam runs outside the Old City wall, a narrow zone on the outside of the wall. Yemin Moshe and Mishkenot Shaananim became the frontier of the conflict. Its residents, the poorer inhabitants who remained, were often fired at by Jordanian soldiers. Now the area is an up-market neighborhood.

In the Six Day War the Israeli army surrounded and shelled the Old City. On June 7th, 1967, they attacked through the western gates and southern gates, including the Zion Gate, and drove out the remaining Jordanian forces.

Ghosts of the soldiers who fought there are seen in street mirrors and live in the walls.

Fences, gates, walls, baebed wire and gardens, 2021

Jerusalem Old City is a place for both living and worshipping. It is crowded, crazily diverse, and physically complex. All communities protect their own domains. Some live literally on top of each other. The result is a three-dimensional puzzle of boxes inside boxes.

Jewish, Christian, Muslim, and Armenian communities comprise the Old City. They all defend their own presence and privacy, sometimes violently. The best known and largest area is the Muslim Quarter, a city within a city. The Jewish Quarter was rebuilt after being destroyed by the Jordanian occupation. About 10% of the Old City’s residents are Jewish. The Christian and Armenian communities have quarters in the west and south corners respectively, just inside the city wall. All the communities try to protect their privacy and integrity using fences, gates, walls, barbed wire, and gardens.

Damascus Gate

The historical and physical epicentre of the Seam is the two square kilometre area outside the Damascus Gate (باب العامود). This gate on the north-west side of the Old City is used by the East Jerusalem Arab community as their major entrance to the city. Inside the gate is a thriving market selling everything you might need: clothes, shoes, food, spices, candy, household utensils, cell phone equipment.

Outside the gate are steps organized like an amphitheatre and used as a social gathering place. Surrounding the steps is a mixture of parks, shops, hotels, bus stations, and car parking.

Border Police, 2020

From 1948 to 1967 all was very different. The Damascus Gate area was a no-man’s land with two separated sandbagged checkpoints, Israeli and Jordanian, on a cobblestone street lined with tank traps. Barbed wire stretched for hundreds of metres. Around the checkpoints were abandoned streets and destroyed buildings. The checkpoints were the only central pathway between East and West Jerusalem. Few passed through the checkpoints: some diplomats, pilgrims, tourists, and UN peacekeepers. Tensions were high, and disputes, sometimes lethal, often broke out between the two sides.

Now, outside the Damascus Gate are two Israeli Border Police posts that overlook the entry steps leading to this gate through the Old City wall. Sometimes there are police at the city gate itself. The gate has become a symbol of the Palestinian national struggle.

There is a history here of violent and deadly incidents: stabbings, shootings. The security situation is often tense, especially during Ramadan, since this is a choke point on the route from Arab neighborhoods to the Al Aqsa mosque in the Old City.. In 2016 there were more than 15 violent attacks outside the gate.

But whenever I visited the steps, it was calm. Vendors sold their wares. I sat in the afternoon sunshine and watched Arabs, Jews and tourists passing though on their way to and from the Old City. The steps were full. People checked their cell phones, chatted with friends, bought fruit juice.

East Jerusalem

The shrine of Shimon HaTsadek in East Jerusalem is traditionally the tomb of Shimon the Just (שִׁמְעוֹן הַצַדִּיק). Shimon is usually identified as being one of two priests with that name from around 300-200 BCE, the Second Temple period.

Jewish Shrine, 2020

The tomb and the area was purchased by the Sephardi Community Council in 1875 and developed as a neighborhood for Sephardi families. In 1947 these residents were attacked by local Arab residents and persuaded to leave by the British Mandate government.

From 1948 to 1967 the shrine and its surroundings were part of Jordanian occupied Jerusalem. After 1967 the shrine became a synagogue and a Torah study centre. The shrine itself is a low-key block of limestone covered by a felt cloth. Fences and barbed wire protect the synagogue worshippers. The area around the shrine has become an ongoing source of dispute, as Jewish organizations mount legal actions to reclaim the original Jewish houses and evict the Arab residents. They of course resist. There are protest graffiti and protest tents, usually empty. Occasionally there is violence. At these times the street is a centre for dramatic live broadcasts by the international news agencies.

My friend Bruce was there for the public Iftar dinner, the evening breaking of the Ramadan fast, at a time of great tension around the Al Aqsa Mosque. The Israeli police had announced a curfew after the dinner. When curfew time arrived, my friend said that it was like a scene from West Side Story - two rival gangs pushing, shoving, and hurling insults.

Reflections

Along the Seam are relics of the past: fortifications, watch towers, trenches, razor-wire. And relics for the future: buildings, recreational facilities, roads, bridges. These relics are made of local stone, dirt, metal, and concrete. They are hard, sharp, persistent. My camera found them, sometimes hidden, lit by the harsh Middle Eastern sun. They define Jerusalem’s history.

People on the Seam walk, shop, eat, talk, sing. They are unaware of being in my viewfinder. In my images these everyday ghosts are often out of focus, facing away, blurred, moving through the edges of the frame, incomplete. These ghosts live not only in the city’s present but also in its past and future.

1 Michael Sager is a photographer and writer living in Jerusalem. In his previous life he was a software and database developer. Since retirement he has developed a new career as a photographer. His favorite subject is his hometown of Jerusalem. He covers its people, its communities, its conflicts, its culture, and its history. He has a Bachelor's degree in English and Politics, a Master's degree in Business Administration, and a Master's degree in Photography. This article is derived from his photography thesis work.