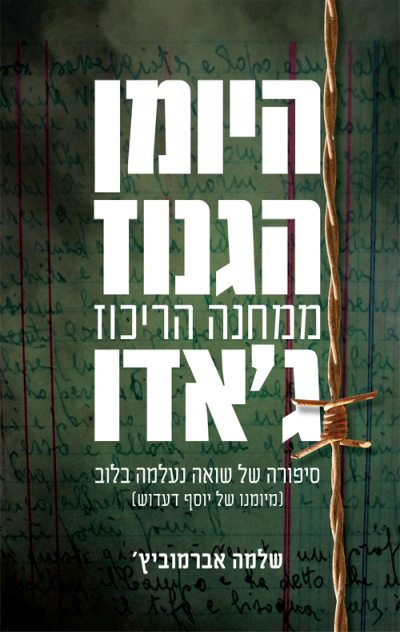

שלמה אברמוביץ', היומן הגנוז ממחנה הריכוז ג'אדו: סיפורה של שואה נעלמה בלוב, מיומנו של יוסף דעדו ש

Shlomo Abramovich

The Hidden Diary of Giado Concentration Camp by Yosef Dadusc

Rishon LeZion : Miskal – Yedioth Ahronoth Books and

Chemed Books, 2020

(192 pages, illustrations, in Hebrew)

[Shelomoh Abramovits ha-Yoman ha-Ganuz mi-Mahaneh ha-Rikuz G'ado: Sipurah shel Sho'ah ne'elamah be-Luv, mi-Yomano shel Yosef Da'dush]

Reviewed by Rachel Simon1

The main contribution of this book is in making general Hebrew language reader aware of the suffering during World War II of the Jews of Libya in general, and those of Cyrenaica in particular: it clearly states, time and again, that the Holocaust (Sho'ah) was not unique to Europe, and happened also in Libya. While several scholarly publications on the topic have been published in Hebrew, both as articles and as parts of monographs dealing with the Jews of Libya, this book is aimed at the general public, and focuses on the German-inspired Italian antisemitic policy in Libya during World War II, which culminated in antisemitic legislation, internal transfers, forced labor, and exiling of enemy citizens. The book was inspired by the diary that Yosef Dadusc (1921-1994) wrote in Italian while being interned at the Giado concentration camp in Tripolitania, as well as by documents and memoirs found long after his death in his personal archive. This material is augmented by the memoirs of several former Giado internees and other Libyan Jews; some published research was also consulted. The bulk of the book is the text written by Abramovich; photocopies of several pages of the diary and a Hebrew translation are included.

Dadusc was born in Benghazi and was among some 2,600 Cyrenaican Jews who were transferred in the spring of 1942 to Giado, an isolated former Italian military camp, about 150 miles south of Tripoli. The internees stayed there until the British army arrived in late January 1943, though their departure was gradual, due to disease, especially the typhus epidemic which had claimed 562 lives, and transportation difficulties. The official reason for the transfer was the collaboration of the Jews with the British Army, which occupied Cyrenaica twice during 1941-1942. To this was added the constant German attempt to bring the Italian regime to take part in the Nazi Final Solution and Jewish extermination. Due to the important role of Jews in Libya's economy, the Italians were slow to follow German policies. Still, the Jews suffered, as did the population at large, due to British and French bombardments, and increasingly from policies aimed directly at them: anti-Jewish legislation, transfer, exile, and forced labor. While Giado was not a death camp, the Jews suffered due to the extreme weather, little and poor food, overcrowding, lack of privacy, and the difficulty in keeping proper hygiene, resulting in the spread of epidemics. The camp was under Italian command, and some guards treated the Jews harshly. While several later memoirs described the suffering of the Jews in Giado, this diary is thus far the only contemporaneous testimony of life in the camp written by an internee. The diary itself held some fifty pages, several of which have been lost. The poor quality of its paper, stains, and erasures made the deciphering of the diary very difficult. Thus, the translation is not of the complete diary.

The book includes a biography of Dadusc, describing his life, work, and communal activities in Benghazi, Giado, and Israel. Also included are glimpses into the history of the Jews of Libya, Italian and German policies and military activities, as well as the British failed and final occupations. Mentioned are the relations of the Jewish Palestinian soldiers who served in the British army with the local Jews and their impact on the Jewish community. The text describes how Dadusc, once settled in Israel, was determined to let the Israeli public know what happened to the Jews of Libya during World War II and his continuous struggle to have official Israeli recognition of Libyan Jews as Holocaust survivors; this was achieved only in 2010. The description is lively, using occasionally modern Hebrew slang (even in the translation of the diary), with the chapters going back and forth chronologically and among the various topics and events, making the text less coherent.

The diary (pages 169-190) describes living conditions in Giado, including the harsh treatment of the Jews by the guards, relations among the internees, their attempts to improve food supply, and the tense relations between the Jews from Derna and Benghazi. The diary mentions Germans only once (page 173) in reference to the Italian and German military (but not inside Giado) while the text refers to Nazis visiting Giado (e.g., pages 55, 61), though memoirs of another internee state that the Fascists didn't let the S.S. enter the camp because they didn't want involvement from above (page 57). No Italians were left in Giado when the British army arrived, and there are no details of what happened later. Parts of the diary are included in the text, at times slightly different and with more details than in the diary's translation. Abramovich also writes that Dadusc had refused to benefit from the help that his Italian employer had offered, namely, to intervene in his favor with the authorities in order to prevent his deportation from Benghazi to Giado. This and Dadusc' statement, which is mentioned several times, including as a motto for the book (page 7): “To the place to which all my Jewish brothers are going-- I'll go as well” do not appear in the translation either. Consequently, it is not clear if all the parts of the diary which were deciphered were translated and published in the book.

The book does indeed play an important role in making general Hebrew language readers aware of what happened to the Jews of Libya during World War II and of the fact that the Holocaust was not unique to Europe. This is done in a lively, unannotated manner, and in somewhat disconnected fashion. It brings to light a firsthand description of life at the Giado concentration camp and the activities of Dadusc in Libya and Israel. The late discovery of the personal archive of Dadusc is encouraging, because it shows that other important sources might still be found. Hopefully these documents, which deserve proper scholarly editing and analysis, will be made publicly available to researchers.

1 Rachel Simon is Middle East studies librarian at Princeton University Library, emerita. Her highly respected study of Libyan Jewish women, is one of her several studies of the Jews of Libya in modern times.