Interview with Gila Green1, Israeli-Canadian-Yemenite Novelist

Interviewed by Judith Roumani2

Transcribed by Gila Griner

Interview was conducted in Jerusalem, at a street café, in the Fall of 2023.

An audio recording of the inteview is also available

Hello, this is Judith Roumani in Jerusalem, sitting down for a conversation with the novelist and teacher Gila Green who lives near Jerusalem and is here for a class in a little less than an hour. I am just catching her to have a little bit of conversation that I thought might also be interesting to our readers.

Hi Gila!

GG: Hi Judith. Thank you so much for meeting me today.

JR: Gila, I really hadn't planned this as an interview, but more just as a conversation. So, you are quite a prolific author these days. When did you write your first short story or novel, and how did it come about that you decided you wanted to write?

GG: I've always been a huge reader and always wanted to write. What I wanted to write, that's a different story. My first degree is in journalism and English lit, so I was initially going in the journalism direction, but that was before I planned to live in Israel. Once I made Aliyah in 1992, I realized that there was very little at the time to do in English. I'm fluent in Hebrew but would not want to work in a second language as a journalist, so I went in the direction of book editing and manuscripts generally, but I was not writing myself. It was a lack that I didn't know how to fill and wasn't sure I had the confidence to do so. After three children and pregnant with my fourth, I did a master’s in creative writing at Bar-Ilan University. I had these very encouraging professors who came in from New York and I just started publishing, simultaneously, while still in the program.

Of course that was the old days, with envelopes, and stamps, and printing out stories.

JR: Waiting for the mail….

GG: Waiting for the mail and paying for them to mail you back the manuscript. You had to get pre- stamped envelopes and it was time consuming. So that's been since 2005 or 2006 and for a few years I stuck with short story publishing mostly in lit magazines and anthologies.

JR: Oh, wonderful, and so you were very much encouraged by your professors from New York, but you yourself are originally Canadian right?

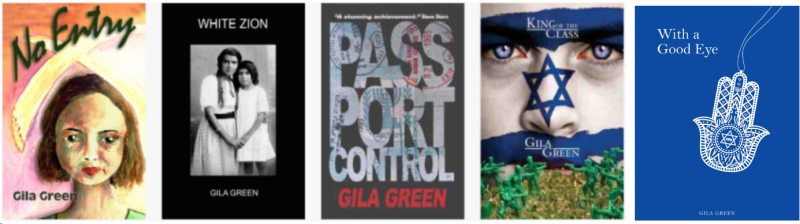

GG: Yes, I'm originally from Ottawa, my husband is South African, so I also spent close to one year living in Johannesburg. White Zion is more or less the thesis that I handed in at Bar-Ilan and much of it was already published within the two years it took me to complete the M.A.

JR: Oh really? Very interesting. We had a review of that in a recent issue, and it's a series of stories, but can you explain to us why White Zion? That is a very unusual sort of term to create.

GG: I came up with the title White Zion before ‘white privilege’ came about. Actually, at one point I was wondering if I should change it, because now the word ‘white’ had become a little bit different, but I decided that was what I wanted it to be called. Originally, my idea was ‘white Zion’, because my father was born here in 1936, and his mother was also born here under the Ottoman Empire and I have just met too many people, even native Israelis, who were very surprised to hear that the original founders of the country were not all from Ashkenazi backgrounds.

Very often if I tell someone my father is Yemenite, if they know anything at all, they will say, 'so when did your family come, in the fifties?’ It's when the majority of Yemenites came. So they are very surprised to learn that some Yemenites arrived in the 1880s in what is known as the First Yishuv—that's when my family arrived.

The title came from me trying to say that ‘Zion’ means the early Zionist enterprise wasn't all white--that was my message; it was an ironic title.

JR: I see, I see that the people who were not white, who were Sephardic or Mizrahi, who might have made Aliyah even before the wave of Ashkenazim, actually had a right to make their voices heard and they have been absolutely overwhelmed in the Ashkenazi nature, the early nature of the state.

GG: Yes, I believe their stories and narratives have been drowned out, there were definitely reasons, such as the overwhelming experience of the Holocaust. Nonetheless, Sephardim and Mizrahim had a lot to do with the founding of the state. I had a Yemenite great-uncle who volunteered to be part of the only contingent of Jews that was allowed to fight the Nazis under British uniform. I don't think it is well known that Jews of Mizrahi descent were also part of this brigade.

JR: Yes, I know it was the Palestinian Brigade. So many Sephardim felt: we didn't suffer as much as the Ashkenazim did. But I've been quite involved with the Libyan community. My late husband was Libyan, and I've been involved with books on these subjects on the history of the war in North Africa and how Sephardim really did suffer. There is a book called The Holocaust and North Africa but in my view it could be called ‘The Holocaust in North Africa’ because many North African Jews did suffer and did die as a result of Nazi and Fascist racism. We have a review published recently of a book on a Fascist concentration camp in North Africa, in the desert south of Tripoli, where Jews were sent as a punishment for aiding the British. Hundreds of them died not through extermination by the Fascists but simple neglect and maltreatment. Something like in Bergen-Belsen. Also, many Libyan Jews were sent to Bergen-Belsen. Fortunately, none of them actually died there. They could have, they suffered.

GG: The Jewish population in Palestine at the time was worried that Hitler was going to make it all the way there, it definitely was a danger. When my father was a child, they were digging trenches (to protect against shrapnel and bullets) in case the Nazis made it to Jerusalem.

JR: Right. Also, the Jews of Egypt were very much afraid of the Fascists and the Nazis coming from North Africa and taking over Egypt.

GG: Furthermore, Jews didn’t feel their treatment under the British was so delightful, I heard enough bad memories about it. They definitely felt that they could be shot on the street for any random reason by British soldiers when they were walking around here in the early 1940s. Again, I'm not comparing pain or trauma, but expanding the pool of Jewish history to include Mizrahim who also lived under the British.

JR: So, this is part of the background of your work, but you are bringing us more current, contemporary situations of the things that happen to Jews who come from a Mizrahi, if we can apply that, background, and how Mizrahim deal with certain disadvantages in Israeli society or in, also, Canada as well, and you base it a lot on your family experiences. Would you like to elaborate on that to us?

GG: Passport Control is a little bit of an extension of White Zion. I took two of the characters I feel people want to know the most, which are the father and the daughter. In this thriller, the heroine, Miriam Gil finds herself living with an Arab Israeli, who identifies as Palestinian, a Druze, a Moroccan roommate, and an Ashkenazi roommate. She struggles to understand the dynamics of what's going on in this dorm room. There are all different tensions. The Druze student's father is an IDF officer, so there's a lot of tension between her and the Palestinian roommate. It’s hard for Miriam, a Canadian tourist, to navigate. She's the one from Canada but she is accepted by the Druze and the Palestinian much more than the Ashkenazi roommate who grew up in Israel, because she has a Yemenite background. The two Arab roommates consider the Ashkenazi Israeli roommate European.

The setup of the novel is based on some of my own experience in Haifa in the dorms, it was the first time that I ever heard that a lot of Israeli Arabs and Druze consider Ashkenazi Jews here Europeans, which I found really puzzling in my early twenties, being confronted with it, it was difficult. Why was I as a Canadian more accepted by them than someone who grew up here? Throughout the novel there are a lot of questions of identity and loyalty.

My new novel With A Good Eye is an entirely Canadian novel that takes place in Ottawa. It's coming out in Montreal but it's already available for pre-order and several people have already told me they received it. I return to Canada, though there is still an Israeli father, who has PTSD as an Israeli war veteran, while the mother is a narcissist and what is often called an absent mother, there are other terms for this, such as ‘dead’ mother and so on. The idea is she is not available for her children.

This novel is also a thriller with a thread of antisemitism. With A Good Eye explores the effects of mental disorders on children who are often left to fend for themselves when their parents suffer from such conditions, particularly in the eighties when mental illness was a taboo subject, there wasn’t a lot of information. It was something to hide and be ashamed of. There weren’t resources, there wasn’t the internet obviously.

GG: It's not all negative---coming from a mixed background. I do find, let’s say as a teacher in college, that my mixed background actually makes a lot of my teaching easier. I find that my students can relate to me a lot better as soon as they realize it. Because I teach students of many Israeli backgrounds, from Ethiopian to Algerian, Moroccan, and Ashkenazi. I find that actually makes it easier for me to relate to my students and understand where they are coming from. Similarly, with my family, my children have all married people with different backgrounds and I feel that sense that it’s OK to explore, came from me. I never limited my children with regard to their friends or what they wanted to explore culturally.

JR: That’s very interesting. So, you yourself, you feel very much at home here and you’re probably a typical Israeli family in the sense that you are very mixed.

GG: It has taken me a long time because I grew up in Ottawa which at the time was a very parochial, conservative society, very ‘Wasp’. I don’t know if anybody knows what that means today or if it's an acceptable term these days.

JR: I think they remember that term….

GG: It was a struggle in such a community. Later, I didn’t fit in over here as someone whose first language is English—right away that can make you an outsider and I didn't fit in over there because of my color, my name, everything about me said "not from here" to people. I am the darkest one in my family and that was always a cause of conversation growing up. At a certain point, I realized that it was actually a benefit, and I changed my view of it and instead of fighting against my identity, I learned to accept it. The writing probably helps as well.

JR: Yes, yes.

GG: As you said, I do feel very comfortable in Israel now, but that has been a long, long process….

JR: Do you think that your writing is therapeutic for yourself, or for your readers?

GG: It’s definitely therapeutic for me. I hope it's entertaining for my readers and insightful. I'm trying to draw them into worlds that they might not necessarily be aware of—Jews and non-Jews. I have non-Jewish readers, and I've received emails like: “I didn’t know that all Jews weren’t really wealthy” after reading my novels. I know that sounds a little bit off, but I it’s not coming from a bad place, they are thanking me for expanding their view.

JR: It’s an innocent question.

GG: Yes, it’s an innocent question, they are very shocked to read that I am writing about a family that struggles financially, who have financial difficulties, and are not particularly good with money.

JR: Just last night I re-read your story “Book Talk” that you published in Sephardic Horizons. I really admire the way you bring a conversation to life between the speaker and the audience. The give and take, the way the ideas ricochet off each other, and the audience which wasn’t very knowledgeable was exposed to totally new concepts. I really like that.

GG: Thank you.

JR: And that was achieved with a minimum of words, it’s very economical with words.

GG: Yes, people have told me that. I am very restrained. I really like the idea of people reading between the lines and not splashing everything in big neon lights. It’s my natural style, it’s not something that I could easily change. Every editor I've ever had tells me to expand, expand. I would probably write even more sparsely if I didn't have those amazing editors who said: a little more….

JR: I think readers like that: Oh, I get what she’s talking about. The way the audience is reacting. Readers have to be more active with their brains obviously, than perhaps reading another writer where everything is spelled out …(interrupt)

GG: I think that’s probably my Canadian literature influence of once upon a time. Furthermore, I'm greedy. I want the reader to be with me, in my head. I want them with me, thinking about what I am saying without me spelling it out.

JR: Would you say you are influenced by A. B. Yehoshua, the way he writes in Mr. Mani, where he gives one side of a telephone call and the reader has to fill in the other side of the conversation. There’s an answer to a question and the reader has to immediately imagine what the question could be.

GG: No. I think most of my literature because I grew up overseas really came and my first influences were very, very Canadian, European. I think that’s probably my Canadian literature influence, I think because I also have a double major in literature. I think that’s a lot, maybe, the Canadian literature vs. American literature. Sort of that anchoring, Alice Munro, and just growing up in Timothy Findley and Alice Munro and Margaret Atwood and Margaret Laurence. The really classic literature that was really drilling very deeply. Probably completely out of style now but it was [in style] once upon a time. Of course, they are Canadian Jewish writers. I’ve always liked international literature. I get that comment a lot, sort of sparse, restrained, lyrical. I think it also reflects a lot of my own psychological state as I've spent a lot of time in my life unable to express myself, as many children are. I am really excited to hear what you are going to think about With a Good Eye now that you talk about it, because that took me years and years to get right. Probably started on and off twenty years ago and just couldn't ever get it. My beta readers were not relating to the characters, who were always too something or other and out of balance. I would have to stop and just write another book and go back and stop and go back. Until I finally had the best piece of advice from an editor, also Canadian, actually Pearl Luke, who said to me: you know what, you’re trying to write two novels at once. Split this into two. So, there is With a Good Eye and there is The Inheritance, which is also coming out in Montreal in another year, 2025.

JR: We will be privileged to read it. Could you please tell us again when it is coming out and who is the publisher?

GG: AOS publishing in Montreal. It’s supposed to officially come out on the 18th of August, which is also my birthday, of next year 2024. But the pre-release is out and if you ask for it, they'll mail it out already. You can also already pre-order on Amazon Kindle.

JR: Wonderful, we are really looking forward to that and thank you so much for giving us your time Gila! I am sure you don’t want to keep your class waiting. Thank you so much for spending time with us today.

GG: Thank you Judith. Given the current circumstances, I wish to add that I pray we all hear better news soon.

1 Canadian author Gila Green is an Israel-based writer, editor, and EFL teacher.

2 Judith Roumani is the editor of Sephardic Horizons.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800