In Lieu of an Editor’s Note

With profound thanks to:

Annette B. Fromm, Gila Griner, and Altan Gabbay, and all our authors

Ladino Romansas for Today’s Children:

A Cooperative Translation Project

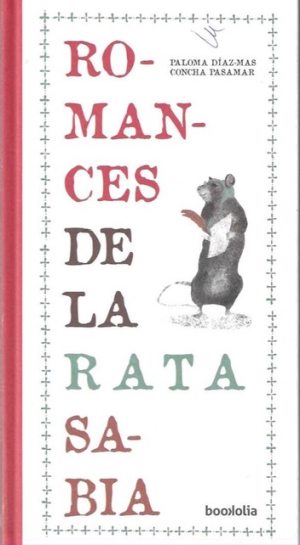

By Rachel Amado Bortnick1

In 2022-23 a group of us worked collaboratively to translate an unusual children’s book, Romances de la Rata Sabia (Ballads of the Wise Female Rat) from Spanish into Ladino (“Romansas de la Ratona Savia.”) Written by the renowned Spanish author Paloma Díaz-Mas and illustrated by Concha Pasamar, the book consists of 16 little stories, each one to four pages long, composed in the poetic format of the medieval Spanish romance. The title of the book is explained in the very first romansa– titled Romance de los Romances de la Rata Sabia: there once was a wise female rat who lived in a library among books and papers, or this way in our Ladino translation:

Avia una ratona savia

Ke savia meldar bien

Morava en una biblioteka

Entre livros i papel.

[….]

And one day the rat got tired of reading and began to write romances and then recite them.

Un dia de los dias

Ya se kanso de leer,

Se metio a eskrivir romansas

I a resitarlas despues

[…]

I (the author) learned the romances that she (the rat) wrote and then I made this book for you:

Las romansas ke eskrivia

yo me meti aprender*

i despues ize este livro

para vozotros tambien

[…]

The subsequent romansas, all in this medieval poetic formula, treat subjects of universal interest to children (pets, colors, secret thoughts, etc.) and of specific interest to today’s youngsters (feminism, immigration, multiculturalism, environmental pollution, etc.)

The author Paloma Díaz-Mas is a member of the prestigious Real Academia Espanyola, Royal Spanish Academy, an eminent scholar of Sephardic history and culture, of Ladino language and literature, and of the Spanish romances. A prolific writer, she has also authored novels and stage plays, but Romances de la Rata Sabia is her first book for children and her first in poetic form. As she explained in a recent Enkontro de Alhad,2 she was inspired to write this book by the old medieval romances that she knows so well.

The word romance (pronounced “ro-mahn-seh”) in Spanish, or romansa in Ladino, denotes a metrical form of poetry of any number of verses in which only the even-numbered lines rhyme. Thanks to the leadership in our editorial team of Dr. Rina Benmayor,3 who is also a scholar of the medieval Spanish romance and of the Sephardic romansas, our translations adhered strictly to the poetic formula of the original versions.

The evolution of the cooperative translation process

In December 2021 I received the book Romances de la Rata Sabia as a present from my friend, Dr. Juana Castaño Ruiz of the University of Murcia, Spain, and after reading it I thought it would be fun to translate the little stories in it into Ladino. On the 28th of August, 2022 I “hosted” the author, Dr. Díaz-Mas, at the Enkontro de Alhad (recording of the meet up) and then I sent a message to Ladinokomunita4 asking for volunteers to take one romansa each to translate from Spanish into Ladino. I copied the entire book and sent a romance to each volunteer. One of the volunteers was Dr. Dalia Kandiyoti, who suggested I invite Dr. Rina Benmayor to take part in the project. Rina’s eager acceptance of my invitation was a fortuitous development for the ultimate success of our project, which in turn received the enthusiastic support and approval of the author, Paloma Diaz-Mas.

The translations we received from the volunteers needed a great degree of revision because we hadn't explained the romance form to them in advance. Thus, Rina and I formed an editorial team with several of the translators who volunteered to work with us. Our team represented the spread of the Sephardic diaspora, stretching from Turkey, Argentina, Israel, Mexico, to the United States. We ranged in age from our 40s to our 80s and had different levels of proficiency with Judeo-Spanish and/or Spanish.

Challenges of translating a romance to a romansa

From November 2022 through March of 2023 the team met via Zoom once or twice a week, working for more than an hour each time. We went through each romansa line by line and word by word, often with long discussions and even arguments before we could arrive at the best possible word that would fit both the meaning and the meter and rhyme of the original. The challenges centered on three areas: the lack of an equivalent word in Ladino, dialectal differences among the Ladino speakers, and Ladino words that didn’t fit the proper rhyme. We don’t have Ladino names for some of the herbs that grow Belardo’s garden, and we don’t know how to say “ housing unit” (for the developer who wants to buy the garden); Izmirlis say “poder” (to be able to), Istanbullis say “pueder” - which should we use?; Some of us say “la sofa”, others say “el sofa”; what shall we do?

We consulted several dictionaries, sometimes every available one, to help us. Mostly we relied on Joseph Nehama’s dictionaire of Judeo-Spanish with French. In certain cases, we were able to leave the Spanish word in because it was included in a Ladino dictionary. Thus, for example in the first poem (quoted above) we left leer (for “to read”) and aprender {for “to learn”) since “meldar” and “ambezar” would have changed the rhyme pattern – something Rina would never allow us to do! (We called her the “romansa police!”)

In some instances, we kept the original Spanish word but added an explanatory footnote, as with the name of the bird avefria (lapwing in English), or alero (eave in English) which we could not find in any Ladino dictionary. Sometimes, the lack of a word in Ladino inspired us to adapt the poem to a Sephardic cultural context. This happened with the plants in the poem about Belardo’s garden. We didn't know the Ladino words for albahaca (basil) or "toronjil" (lemon balm), so, in a final re-edit, Rina and I decided to substitute ruda i yasemin / rue and jasmine, which are plants that can be found in abundance in Sephardic gardens. We explained in a footnote that these are not direct translations of the Castilian, but are common plants in Sephardic gardens.

The plants in Belardo's garden were just one example of how we “Sephardized” or "Judaized" our translations. In the “Romansa ke dize Ladra Perro; Ladra Perro,” about an abandoned dog which had been bought as a present for el dia de Navidad, its translator, Gloria, changed that to “la fiesta de Hanuká” which happily also preserved the accented rhyme in á! In another poem, La Romansa de las Tres Palavras, the young immigrant boy learns his first words -- rock/ scissors/paper – “en Ladino!”, not en español, as in the original. However, in another case, we had to leave in the formulaic reference to "Manyanita de San Juan," in the “Romansa de la Barka ke Viniya de Leshos” about exhausted refugees arriving in a rudderless boat on that particular holiday morning. We explained in the footnote that this is a pagan and Christian holiday. We all learned from Rina that the rhyme patterns and formulaic phrases in these poems came from old Spanish and Sephardic romansas.

We were in correspondence with Paloma Diaz-Mas when we embarked on the translation process and again at the end. We sent her the edited translations, and she was very pleased with them, especially with the Sephardic and Jewish elements we had introduced. She also offered some minor suggestions and corrections which we appreciated.

You can help get “Romansas de la Ratona Savia” published

When we began this project, we just dove into the translation without giving much thought to what we would do with it once we were finished. We just enjoyed the entire process, all the while hoping that these entertaining and wonderful little stories would be published and used somehow to teach Ladino to children, and maybe teach them the romansa form. After our translation task was complete, we decided that we wanted to publish a bilingual Spanish/Ladino book with the original illustrations. After much research and discussion, we reached an agreement with the original publisher, Bookolia, and subsequently, to help us raise the needed funds, the Sephardic Jewish Brotherhood of America opened an account to which all lovers of Ladino can make a donation.

To conclude, the experience and the results of our project confirm, in our view, that reviving the Sephardic practice of translation ultimately strengthens the survival and perpetuation of our language. It will be a true 'maraviya' to see our labor in published form.

At this writing we are halfway to our goal in the money we need to make this maraviya happen. You can help complete the process with your donation of any amount at the website given, or by sending a check, made out to the Sephardic Jewish Brotherhood Foundation with memo to “Romansa Publication Fund” and sending it to: Sephardic Jewish Brotherhood, 67-67 108th Street, Forest Hills, NY 11375.

To donate by Pay Pal:

Thank you!

Endorsed by Sephardic Horizons and Judith Roumani, editor

1 Rachel Amado Bortnick, born and raised in Izmir, Turkey, is a retired ESL teacher living in Dallas, Texas, who has been active in the promotion of Judeo-Spanish language and culture for many decades. She is featured in the 1988 documentary film, Trees Cry for Rain: a Sephardic Journey and, in 1999, founded Ladinokomunita, the Ladino correspondence group on the Internet, which now has over 1600 members from 40 countries.

2 Weekly Sunday programs by Zoom carried out entirely in Ladino.

3 See: https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/sephardic-ballads-romansas-benmayor-collection/

4 Ladinokomunita is a correspondence group on Ladino: https://ladinokomunita.groups.io/

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800