Two Sephardic Families Found

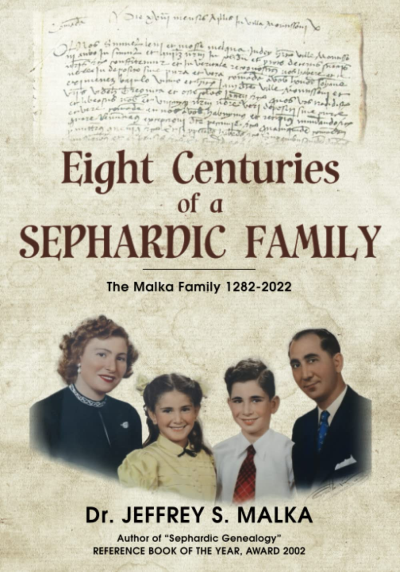

Dr. Jeffrey S. Malka

Eight Centuries of a Sephardic Family

The Malka Family 1282 – 2022

Vienna, Va.: Jeffrey S. Malka , 2022

ISBN-10: 97809860961

Joe Youcha

What Kind of Past

A Balkan Sephardic Family Story

New York: Jewishgen.Inc, 2023

ISBN-10: 9781954176799

Reviewed by Annette B. Fromm1

The authors of these two recent memoirs take very different paths in tracing the histories of their families. One, written by a skilled genealogist finds the distant roots of his ancestors in thirteenth century Spain, fifteenth century Morocco, and then more recently distant Sudan via Tiberias. The other writer takes efforts to learn the history of his ancestral community in the Balkans. In so doing, he connects his own identity to that of Bitola and not-so-distant family members.

Jeffrey Malka, in Eight Centuries of a Sephardic Family: The Malka Family 1282-2022, set about tracing eight centuries of his family, what he calls, “A sort of memoir” (xiv), though he also modestly admits that his richly illustrated volume is only a “snapshot overview (1). He combines texts about the history of his immediate family with brief explorations into related topics that enrich the already surprisingly splendid family story.

The book starts with a long historic view of Jewish life in Spain since before the Visigoths through the Inquisition. Much of his information is based on extensive research in Spanish archives exploring the various locales where his ancestors lived. He then traces the family name to Morocco where Malkas were found, primarily in Fez, from the thirteenth century. Many served as distinguished rabbis in the major Jewish communities in the country.

The family patriarch, Rabbi Shlomo Malka, came from such a long line of rabbis in Morocco. At the end of the nineteenth century, he moved with his wife to Tiberias where he became a rabbi. Early in the twentieth century, when he was only twenty years old, Rabbi Shlomo was invited to relocate to Khartoum, Sudan, to organize a Jewish community which was mostly Sephardic with Jewish merchants from Egypt, Iraq, Rhodes, and Turkey.

Malka next explores the life of his father, Eli, a Jewish son of Sudan. He went into business there rather than following the footsteps of his ancestors. While on business in Cairo his father met his Ashkenazi wife. In writing about his family, Malka shares a number of highly difficult personal stories. Next follows his own life story which took him from childhood in Khartoum to school in England, to medical school in Switzerland where his parents maintained an apartment, and to life in the United States. He had a successful career as an orthopedist and raised a family.

When he retired in his early sixties, Malka took up a hobby which he has pursued ever since, Jewish genealogy. His goal was to fill the gaps in a very Ashkenazi-centric field and raise awareness of the wealth held by so many non-Ashkenazi families. This has been his quest since then, one for which he should be thanked.

Malka’s easy to read text brings to life images of Jewish life in Morocco in the late nineteenth century, setting the visual scenes of where generations of his family lived. He also provides historical information that enriches the reader. His text is filled with family stories. The tale of how the recently buried corpse of his grandfather’s highly respected brother was disinterred and ransomed by local Berber tribesmen (in fact, this narrative appears several times in the book). Another is a story of how his grandfather left Morocco with his young wife under the cover of night.

Also supplementing the rich text about his family are extensive timelines filled with historic milestones, other timelines tracing the name or the family in pre-expulsion Spain and Morocco. Brief vignettes following the main text of the memoir provide additional biographical information about family members, including detailed family trees. Photos of weddings and tombstones are also provided. Closing the book are chapters about Jewish history and life in Sudan, his own memorable memories of youth in Khartoum, and more. More vignettes drawn from his lifetime filled with remarkable experiences in Sudan, Switzerland, Morocco, and the US along with appendices round out the book

Eight Centuries of a Sephardic Family is much more than a simple memoir. The author, a genius genealogist has provided rich context of the various places where the Malka family lived to finally end up with his immediate family.

In the relatively thin volume, What Kind of Past, A Balkan Sephardic Family Story, Joe Youcha not only introduces readers to stories of his Sephardic family. He also seeks to understand his life and newly-found connections to these distant relatives. In his quest, Youcha comes across unexpected intersections where his life-long interests overlap with those of the family.

Youcha, like many Jews, is the child of a “mixed marriage” between Ashkenazi and Sephardi parents.2 His father’s family came from Bitola (Monastir) in what is now North Macedonia. He explains that his mother’s Eastern European family stories were more foregrounded than his father’s. By and large, food traditions represented the latter’s heritage. He does, however, refer to family stories heard especially from an aunt, his father’s sister. Family stories provided Youcha with names of relatives who lived in Bitola and possibly the street(s) on which they lived.

Even though more scholarly works about non-Ashkenazi communities are being written in recent years, people like Malka and Youcha are filling the voids of individual, sometimes, convoluted, and often extended family histories. Like Malka, Youcha starts with a brief recounting of southern Balkan Jewish history. Throughout the text he introduces readers to various aspects of Jewish life in Bitola as well as life in New York City.

Youcha takes readers on voyages that crisscross the globe starting with his own first visit to Bitola in 2018, at his Ashkenazi wife’s insistence. There, they visited museums and archives, cemeteries, and Holocaust memorials in former Jewish neighborhoods. As he excavates the various chapters of the family history we are taken to Bitola from 1911 through the war years and the Holocaust, then to the present day. Simultaneously, we are taken to New York of the twenties, thirties, and forties. Youcha introduces family members and others who influenced his ancestors. Readers learn about the role of the Alliance Israélite Universelle on his great grandfather, Victor, who attended an agricultural school in Tunisia with several other young men from his hometown. We follow Victor to Canada and finally to New York City. Interspersed with this information are aspects of the lives of his family.

As Youcha learns about his ancestors and the milieu in which they lived, he internalizes all that he has gleaned. Unlike Malka, Youcha’s explorations of his father’s history are coupled with what seems to be an exploration of his own identity. Music and musical instruments are a repeated thread weaving together connections in the search for his family. Along the way, he was drawn to the oud, a Middle Eastern stringed instrument similar to a lute. Youcha started his musical investigations including seeking musicians and music in the US; he also began constructing an oud. This line of inquiry started during the 2018 Bitola trip when he found several photographs of Jewish mandolin orchestras on display in the Holocaust Museum in Skopje. As his research continued, he learned that the musical connection ran even deeper; one of his aunts played in the International Ladies Garment Workers Union Local 148 Mandolin Orchestra in 1934. Youcha’s personal musical heritage explorations led him to understand more about his Sephardic ancestors.

These two very distinct memoirs are admirable additions to the growing literature about Sephardic Jews. Each author brings to light interesting information about their families and the extended communities to which they belonged, enlarging our knowledge of Jewish life in Morocco, Sudan, and Bitola. They are filled with illustrations that bring the family members and their stories to life. Both are engagingly personal and easy to read.

1 Annette B. Fromm is a museum specialist, folklorist, and lecturer in Romaniote and Sephardic studies and associate editor of Sephardic Horizons.

2 Spoiler alert, my Ashkenazi father, Marvin Fromm, married, my Greek-Jewish mother, Mollie Bacola, in the 1930s of New York City.