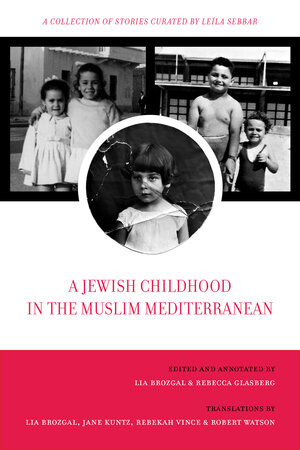

Lia Brozgal and Rebecca Glasberg, Editors

A Jewish Childhood in the Muslim Mediterranean:

A Collection of Stories Curated by Leila Sebbar

Oakland: University of California Press, 2023, ISBN 9780520393394

Reviewed by Ruth Ohayon1

The short autobiographical stories in this collection assembled by Leila Sebbar were originally written in French. The French title, Une enfance juive en Méditerranée was published in 2012. The French-Algerian author prompted the authors to reflect on their childhoods. The Jewish writers and scholars (thirty four in total) born between 1935 and 1955, originate from the Middle East and North Africa, in particular Turkey, Lebanon, Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. The chapters organized geographically from East to West, delineate early life experiences of growing up in countries colonized by France or where Islam was the dominant religion. The authors “have in common a religion, a region, a language, and ultimately, the experience of exile” (xiv). The Mediterranean represents a multiplicity and mosaic of cultures, and serves as geographic and cultural frames for the coming of age tales.

Leila Sebbar writes in the Preface “it is from my position of exile that I explore…a Jewish and Mediterranean that is, today orphaned of the Jews who lived there before Islam” (1). Jewish settlements predated the Muslim conquest in the seventh century.

Dominant and intersecting leitmotifs include, navigating aspects of multicultural Jewish identity, language, sensorial memories, discrimination and anti-Semitism. The writers express painful and pleasurable childhood memories.

Each chapter is preceded by a country overview which is valuable for the historical context of the stories. The Turkish author Lizi Behmoaras shares memories of her school days in Istanbul. Issues of identity and language surface. She could not admit to speaking French or Judeo-Spanish at home. Turkish is the school and street language with focus on speaking Turkish at home so as to assimilate into the culture. She writes “I have two languages at home, a third for the street and school, a fourth for religious holidays” (13). Behmoaras asserts that in the 1940s, the “wealth tax” for the minorities ruined many families, and if not paid resulted in being condemned to labor camps. Her grandmother bemoaned the confiscation of rugs, crystal, Lalique lamps.

The Lebanese writer, Lucien Elia reflects upon the day in May 1948, the creation of the Jewish state, when protesters poured into the dead-end alley in Beirut where she resided, and chanted “ Palestine is our country, and the Jews are our dogs” (44). Upon her return thirty years later, all that remained after the destruction of the alley was the citron tree.

Egyptian authors, Rita Rachel Cohen, Mireille Cohen-Massouda, and Tobie Nathan, reminisce about sensorial experiences associated with their childhood growing up in Cairo or Alexandria: the orange blossom water, the incense burning that perfumed the rooms in homes, the flavor of apricot paste, the aroma of spices, jam from rose petals, the traditional dish of fava beans. In addition, Rita Rachel Cohen comments on the language: “It was only through leaving and coming back that I rediscovered…the Egyptian language that make me dance, makes me dream, that opens my heart, that brings me joy in motion with the special quarter-tone that belongs to ‘oriental music’” (62).

In the historical overview of Tunisia, we learn that it was the only Arab nation to be occupied by the Nazis during World War II. Several thousand Jews were forced to work in labor and internment camps (81). Annie Goldmann recalls the day in November 1942 when the German tanks rolls into her small town, the confiscation of the family’s apartment, the closing of the school, her father’s enlistment in the labor camps. Nine Moati, however, writes about experiencing joy whenever she returns to Tunis: “To see the women’s smile…to rediscover the beauty of Boukornine (national park), the sea, the cypress trees, the scent of jasmine, the magenta bougainvillea that pours over the whitewashed walls, yes those are the reasons why Tunisia will always be the country of my heart” (110).

The Cremieux Decree of 1870 granted French citizenship to a majority of Algerian Jews, while Algerian Muslims remained colonial subjects (121). The Decree led to renewed anti-Semitism among European settlers and Muslims. Forty years later, the Decree was rescinded by the Petain’s government.

A number of Algerian writers echo the sentiment that Jean-Luc Allouche describes: “We were immersed in an amniotic symbiosis with Arab culture” (128). Joelle Bahloul remarks on her childhood, “I also prefer to retain my sensory memories of the fragrance of jasmine and eucalyptus, of the glorious colors of bougainvillea, and of the taste of…calentita (a dense chickpea bread)” (132). For Line-Meller Said, it is the smell of roasting peppers over charcoal. Patrick Chemla’s childhood was dominated by war and learning that Arabs were not to be trusted. Memories of sorrows and delight, disillusionment and hope formed many Jewish Algerian writers’ recollections. Roger Dadoun’s title of the story, “Kaddish for a Lost Childhood,” encapsulates sentiments shared by a number of writers. Once Algerian Jews received their French identity cards they began losing their Jewish identities, “From the Arab Jews they once were, they became not French Jews, but Jewish French men and women.” (170). But Jews and Muslims shared the same languages, Arabic and French; the same prayer schedule; musical roots; and the marketplace (180).

What led to the mass exodus of Moroccan Jews between 1948 and 1951 was a combination of events including the creation of the state of Israel, independence from France, and a growing Zionist movement. Over twenty-eight thousand Moroccan Jews immigrated to Israel (195). Ami Bouganim yearns for his coastal home of Essaouira (Mogador). The poetic story, “God’s Cradle,” includes evocative images of the landscape: “The sea spray saturated itself with the black incantations of the Gnawas and the soft insinuations of swallows, the murmurings of soothsayers and the litanies of beggars” (207-208). Other writers express the loss of a world of fragrances, moments of joy with families, laughter, and storytelling. Lucette Heller-Goldenberg writes about 1950s Judaism in Morocco, “a mixture of East and West, of tradition and modernity, where Jews wearing both traditional djellabas and three-piece suits all spoke to one another in both Arabic and French” (221), and adds “All that’s left is memory” (222).

A Jewish Childhood in the Muslim Mediterranean is a fascinating collection of coming-of- age stories, growing up Jewish in a multitude of countries that form the region geographically and culturally. The variety of writers, experiences, countries create a powerful and significant tapestry of the Jewish world that was erased after mass migration and creation of a diaspora outside the Mediterranean. The memories and recollections are haunting and filled with sadness, nostalgia and loss.

1 Ruth Ohayon, PhD, is Professor Emerita at Westfield State University in Massachusetts. She focuses on postcolonial literature, Francophone women writers, Caribbean, and diasporic studies. She recently taught a course on the Literature of the Holocaust.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800