The Musical Poetry of Three Nineteenth Century Sephardic Women

By Leonard Stein1

This essay will examine obscure work of the most famous Jewish women from the nineteenth century: Grace Aguilar (1816-1847), Penina Moïse (1797-1880), and Emma Lazarus (1849-1887). As Sephardic writers, they wrote not infrequently of exile, particularly of their Spanish and Portuguese heritage, of Jewishness in broader society, and of their pride in establishing a new homeland. Furthermore, their writing was profoundly impacted by their relationship to music. Aguilar played harp and would cry at recitals, Moïse wrote many hymns for communal singing, and Lazarus printed concert reviews and composed poetry specifically dedicated to Chopin and Schumann. To study the dynamic between these women’s poetry and musical compositions I offer new directions in understanding the formation of their modern Sephardic identity. Not only do these women articulate a recurring theme of diasporic longing in poetry, but melodies that turned their texts into songs similarly betray a sense of diasporic movement of geographical influence and adaptation. This essay, thus, aims to bridge literary and music studies as a means to foreground the significance of the poets’ space and alterity in broader British and American society.

Grace Aguilar

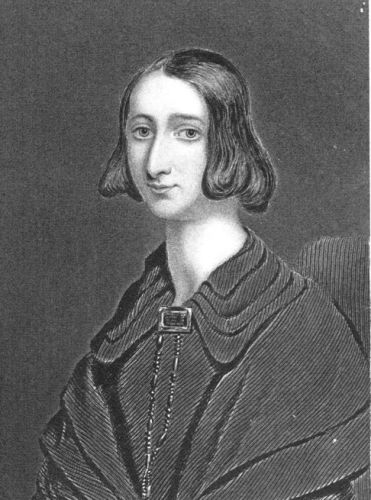

Fig.1 - The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection,

The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1838-1899.

Born in 1816 to Portuguese crypto-Jewish emigrants, Grace Aguilar was one of the first modern Anglo-Jewish published writers. Her domestic, moral fictions and anti-Catholic, gothic stories of Inquisitional Spain (partly drawn from her family’s oral history) appealed to a Protestant Victorian readership, and introduced them to a sympathetic, publicly Jewish woman who dispelled archaic notions of false national allegiance. As she wrote in the very last essay published in her lifetime, Jews are “Jews only in their religion—Englishmen in everything else” (Aguilar, “History” 332).

The extent of this internalized Englishness appears throughout her writings of medieval Spain, such as in the last stanzas of her 1843 poem, “Song of the Spanish Jews During Their ‘Golden Age’”:

Home of the exiles! oh ne’er will we leave thee,

As mother to orphan, fair land we now greet thee,

Sweet peace and rejoicing may dwell in thy bowers,

For even as Judah, fair land! thou art ours.

Oh, dearest and brightest! the homeless do bless thee,

From ages to ages they yearn to possess thee,

In life and in death they cling to thy breast,

And seek not and wish not a lovelier rest. (l. 21-28)

The song imagines eleventh-century al-Andalus, when Jews like Solomon Ibn Gabirol, Moses Ibn Ezra, and Judah Halevi initiated a new era of Hebrew poetry largely influenced by the forms of contemporary Arabic poetics. The wide spectrum of Hebrew genres and styles of the “Golden Age,” however, bear no relation to Aguilar’s writing. Even when channeling an ancestral voice, Aguilar in “Song of the Spanish Jews” betrays a remove from her subject, instead writing in the conventions of a Romantic pastoral and through the ironic perspective of a Spanish Jewry’s future expulsion from the land. Despite a family history that informed her depictions of the horrors of Inquisition Spain, she had little information about Muslim-ruled Spain from centuries prior, neither historiographical access nor the language to read Andalusian poetry; in fact, it appears Aguilar only learned about this Hebrew literary history from a few inaccurate paragraphs written by the English clergyman and historian Henry Hart Milman.

When Grace Aguilar died at thirty-one in 1847, her mother Sarah devoted her life to publishing her daughter’s prolific work, unpublished novels, essays, poetry, prayers, and even sermons her daughter explicitly forbade her from printing while alive. While these efforts helped preserve Aguilar’s literature for posterity, I found a curious song at the music collections archive in the British Library that has not yet been mentioned in any scholarship to date, originally printed with the assistance of Grace’s younger brother Emanuel Aguilar (1824-1904). After studying piano and composition in Frankfurt, Emanuel returned to London to make a living as a teacher and composer, relying on local poets for new compositions. He worked intimately with Christina Rossetti to compose a cantata for “Goblin Market,” for example, eliding the poem’s eroticism so it could be sung by school children.

Emanuel Aguilar

Fig.2 - Portrait at Jewish Music Research Centre.

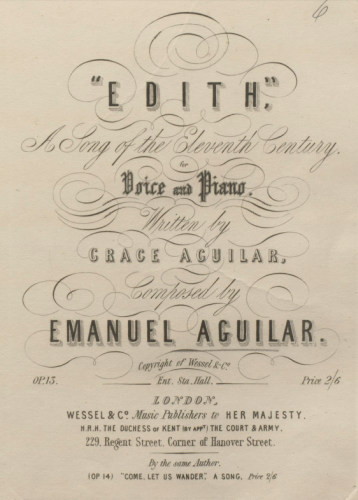

Four years after Grace’s death, Emanuel printed “Edith: A Song of the Eleventh Century for Voice and Piano,” a song created out of a poem he found from his sister, and, interestingly, set in the same period as her “Song of the Spanish Jews” (See Figure 3). “Edith” is a medievalist reimagining of the Battle of Hastings of 1066, when William, the Duke of Normandy, defeated the last Anglo-Saxon king, Harold Godwinson, during the Norman Conquest. According to medieval Latin annals, referenced as an epigraph to the printed song, Harold’s corpse was so mangled on the battlefield that monks seeking to bury him sent his former wife, Edith Swan-Neck, also known as Edith the Fair, to identify him.

Fig.3 - Title page of Grace Aguilar and Emanuel Aguilar’s medievalist

song, “Edith,” 1851. British Library.

The poem depicts the aftermath of this decisive battle with a focus on Edith, a brave, solitary woman searching through the hazy field to find her lost love. Since this poem has not been published elsewhere, I quote it here in its entirety:

The moon up rose in lurid red

Where clouds of tempest lower;

And silence, silence o’er the field came down

At midnight’s awful hour.

‘Tis hushed, save hurrying tramp of horse,

All madly rushing by;

Save smothered groans and muttered prayers,

Where dying warriors lie.

Save where the heavy roll of drum,

The trumpets changing sound.

At distant intervals awake

The answering echoes round.

And they have sought from ghastly heaps,

Their monarch to remove

But dead was like dead!

And vain the search to all save love.

Hark! distant chimes from yon old tower

Fall on the midnight ear,

And solemnly in mournful train

The shrouded monks appear.

What gleams amid those holy men

So lovely yet so frail?

They’ve called for love, to find the slain;

And oh! it will not fail it will not fail.

She doth not shrink, as one by one

She glanceth o’er the dead,

Till on one pierc’d and bloody brow

The torches light is shed

Behold! Behold your noble King,

Go bear him to his rest!

For me! For me! Death heard the prayer

and laid Her softly on his breast.

While far removed from Spain, the song does convey another strain of imagined ancestry, where the image of a medieval woman aligns with the poet’s own claims to early English history (and perhaps personal history as well, since Grace and Emmanuel spent their childhood by the coast of Hastings). Unlike “Song of the Spanish Jews,” the printing of “Edith” offers explicit music in the form of a chamber scena, a quasi-operatic song of voice and piano that displays Emanuel Aguilar’s virtuosic technique.

Fig.4 - Measures 21-29 of “Edith,” 2, 1851. British Library.

The piece starts in C minor and quickly modulates keys, time signatures, and tempos to replicate the intense confusion and grotesque landscape of the historical scene. For example, during the lines “‘Tis hushed, save hurrying tramp of horse, All madly rushing by,” the tempo speeds up to Poco piu mosso (“with a little more movement”) and pairs of octaves played on the piano in accented eighth-notes mimic the sound of galloping (See Figure 4). By conveying this bygone cataclysm, the music’s dissonance makes for unpleasant listening. As in “Song of the Spanish Jews,” the melody betrays none of the family’s Sephardic culture, nor even English musical history, but the unmistakable imitation of German composers like Carl Lowe and Louis Spohr who informed Emanuel’s development in composition in Frankfurt. The transcription, in other words, reveals a musical alterity of multiple degrees, both temporally and geographically from the Aguilar home.

Looking further, we may consider that Grace Aguilar’s English poem appears nowhere else but here as sheet music, beside another kind of poetry, formatted as musical notation, a text where words and sound collaborate with one another. The hand that wrote of the solitary woman searching for her love is embraced, beyond the grave, by the hand that wrote the music to surround her words, a melody transcribed above her poem, with the piano accompaniment below, like a sibling embracing her. Emanuel’s composition provides posthumous engagement, and in the creative inverse of Edith and King Harold, a man searches for a text to keep his sister alive.

Penina Moïse

Fig.5 - Portrait by Theodore Sydney Moïse, c.1840. John L. Loeb, Jr.

Database of Early American Jewish Portraits.

Like Aguilar, Penina Moïse’s patriotism arose out of familial exile. The first Jew to publish a collection of poetry in America, she was born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1797, where six years earlier, her Sephardic parents arrived after fleeing the French colony of Santo Domingo in the middle of the night when a slave alerted them of the ensuing Haitian Revolution. In Charleston, Moïse’s family joined the long-established Congregation Beth Elohim, which in 1825, splintered when younger members petitioned for changes to the synagogue’s traditional liturgy and customs, a fractious communal process that would propel the American Jewish Reform movement. For decades, Penina was an active member, writing most of the new, original, and emphatically English hymns for her congregation.

Moïse called her hymns a “beautiful harmony,” her poems inextricably woven into communal rhythm and melody. Hymns provided the worshipper, through melody, a means to transcend the limitations of poetic language when expressing “God’s presence or powers” (“Hymn 127,” 114). The implications of this harmony are illustrated in her consecration hymn. A couple years after the original synagogue was destroyed in the great Charleston fire of 1838, the Beth Elohim congregation built a majestic new structure with imposing Greek Revival architecture. To consecrate the new temple on the day of its reopening, the community sang a special hymn that Moïse wrote just for the occasion, which begins:

When Faith too young for a sublime creed,

Her simple text from nature’s volume taught,

She ‘wakened Melody, whose shell and reed,

Though rude, upon her spirit gently wrought.

But soon from sylvan altars she took wing,

And music followed still the angel’s flight;

Savage no more, she touched a golden string,

And sung of God, in Revelation’s light.

Lend, our chords, ye seraph-pair,

The soul of Jesse’s son,

That we may, in harmonious prayer,

Exalt the Holy One! (Hymn 1, 1)

In this hymn’s conceit, the language of poetry requires musical assistance if offered to God and this assistance transfigures the character of Melody from barbaric to divine. Moïse subtly references the most heated controversy of Beth Elohim at the time. Sheet music for the hymn has not survived, but it was almost certainly performed with the assistance of an organ, an innovation previously introduced by the reformed congregation and that had provoked years of rancorous debate, a communal schism, and lawsuits. Thus, “Our chords played in harmonious prayer,” refers not only to the notes on the organ or the wedding of text and sound, but a plea to quench a discord that could obliterate, like a great fire, one’s spiritual home; a community amidst the sylvan alters of biblical antiquity no longer, but in the new Promised Land of Charleston, South Carolina.

It was during this very consecration ceremony on March 3, 1841, that Beth Elohim’s cantor, the Ashkenazi Gustavus Poznanski, proclaimed, “This synagogue is our temple, this city our Jerusalem, this happy land our Palestine, and as our fathers defended with their lives that temple, that city and that land, so will their sons defend this temple, this city and this land” (qtd. in Rosen 1-2). These words turned out to be painfully accurate, since his son, Gustavus Poznanski Jr., died in battle in 1862, just months after enlisting in the Confederate States Army in Charleston. Moïse, like the rest of her congregation, supported the war as a sacred duty, proving their loyalty and patriotism in the state they lived in.

Shortly after South Carolina seceded from the Union in 1860, Moïse printed in the Charleston Courier a rousing battle song, called “Cockades of Blue,” after the ribbons of South Carolina’s Minute Men, a song conveniently ignored in collections of her poetry, with highly contextual stanzas such as the following:

Hurrah for the Palmetto State!

Whose patriots the "Minute" await

That shall summon their band

To engage hand to hand

Any foe that dare enter its gate!

Hurrah for the Sectional Star

Whose light shall be seen from afar

To break through the cloud

That its glory would shroud,

And its bright, Southern aspect would mar! (qtd. in Harby 24-25)

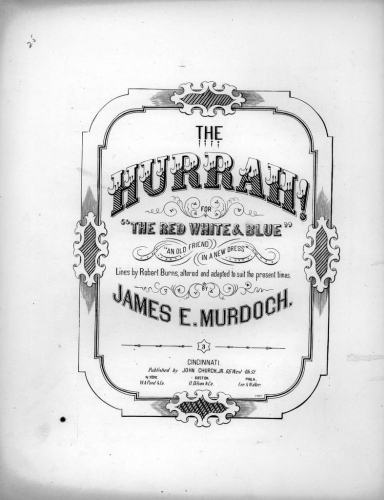

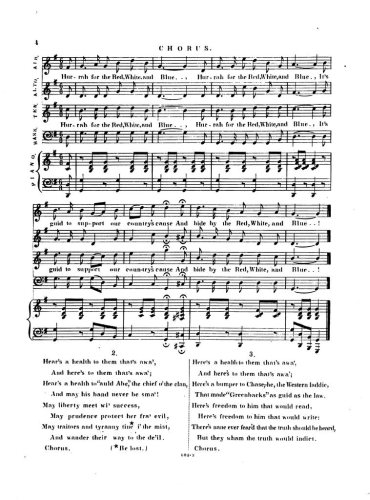

For all its chauvinist pride in her southern homeland, the texts blatantly rewrites a Scottish jig, “Hurrah for The Bonnets of Blue,” a poem found in a letter Robert Burns once wrote to a friend and published posthumously. The song celebrates the Scottish Jacobite army, whose uniforms consisted of white cockades on blue bonnets, as sported by the Young Pretender, Bonnie Prince Charlie. Burns’s song nostalgically cheers the failed reclamation of the House of Stuart to the British Throne, but was eventually appropriated by both Confederates and Unionists during the war. In January 1864, the actor James E. Murdoch and public advocate for the Union army, printed his own version, “Hurrah for the Red, White, and Blue,” because, as he wrote in the Cincinnati Daily Commercial, Burns left the world a political song “that sings itself…it breathes the spirit of good fellowship, and an admiration for honest purpose, patriotic devotion to country and freedom, and whatever is honorable or noble in man or woman” (Murdoch 154). Unlike Moïse, Murdoch reveals the song’s foreign patriotism by attempting a Scots dialect, with lines like “here’s Abram Lincoln, a chief that’s na’ winkin’, but bred wi’ an axe in his paw” (see Figure 7).

Fig.6 - Title page of “The Hurrah for the Red, White & Blue,” Murdoch’s

version of a Robert Burns jig.

Library of Congress.

Fig.7 - Sheet music of Murdoch’s Scots-like jig supporting the Union

army, p. 4. 1864.

Library of Congress.

Like the German Lieder that informs a song of medieval England by a poet descended from Spain, Moïse’s rousing song for her resolute homeland, upon closer inspection, appears but a jumble of musical geography. The Scottish jig arrived in America through New York’s Park Theatre in 1827, when it was sung by British child actress Clara Fisher in her American debut performance, and similarly printed in Richard Peake’s The Hundred Pound Note, an English farce about Irish people, a year later. From there, the song was published in 1845 in The Southern Warbler: A New Collection of Patriotic, National, Naval, Martial, Professional, Convivial, Humerous, Pathetic, Sentimental, Old, And New Songs in Charleston, where Moïse would have read it. After that, the song was wielded for American political purposes, supporting either secession (in Moïse’s version) or the Union (in Murdoch’s version). Considering the song’s historical development, Moïse’s expression of patriotism emerges as unmoored from its origins as the Orthodox traditions of the poet’s Sephardic community.

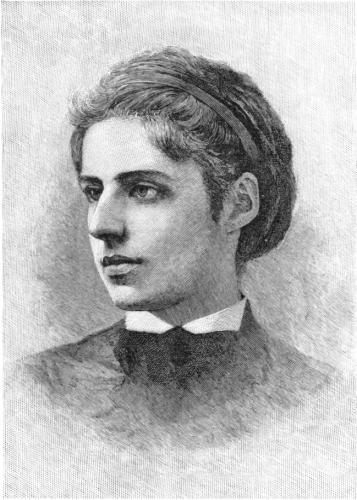

Emma Lazarus

Fig.8 - Photograph by W. Kurtz, engraving by T. Johnson, in The Poems of Emma

Lazarus, Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1889.

Another fascinating example of literary and music intersections related to the subject of Sephardic women appears in Hymns and Anthems Adapted for Jewish Worship, a hymnal compiled and printed by a Prussian-raised Reform rabbi in 1886, Gustav Gottheil, for the Ashkenazi Temple Emanu-El in New York. In a decade-long passion project, Gottheil reviewed the Jewish and Christian hymnals at his disposal and created his own ideal anthology; unlike other hymnals, his did not only contain liturgical songs, but poems on humanity, mortality, and nature. Many of the poems for the temple were not written by Jews, but by famous Scottish, English, and American Christian poets, Romantics and Transcendentalists, and some contemporaneous poets like John Stuart Blackie; many of these poems have no clear relationship to Jewish tradition.

Nevertheless, Gottheil, like other Wissenschaft Sephardiphiles, attempted to introduce unknown Andalusian poetry into a new kind of American liturgy with the help of New York German-fluent poets now forgotten, like Deborah Janowitz and Addie Funk, but also Emma Lazarus, a towering figure in the canon of Jewish American literature. In an extensive biography he wrote about his father, Richard Gottheil described the unusual character of Lazarus, “a gifted poetess of Sephardic stock,” he wrote, “but one whose muse had never sung to the Jewish spirit.” (61) When Gustav Gottheil approached Lazarus to look over his sermons, written in his rusty English, Lazarus declined, saying she “did not think she could be of aid, in view of the fact that the basic Jewish feeling in her was entirely wanting.” The poet’s famous Jewish activism and her printed essays against anti-Semitism were partly indebted to Gottheil, who took her to visit and care for the poor, sick Russian immigrants arriving in Wards Island in 1882. Of course, her legacy-defining sonnet, giving voice to that giant neoclassical statue, La Liberté éclairant le monde, compactly distills America as a nation of liberty-seeking immigrants, but I want to focus on another, less-known event that helped shape her Jewish identity, one that sprang, curiously enough, out of Gottheil’s hymnal.

In 1877, Gottheil introduced medieval, Andalusian literature to Lazarus by asking her to translate three poems, which were by Solomon Ibn Gabirol, Moses Ibn Ezra, and Judah Halevi. Even though she was fluent in French and German, and even printed translations of Heine as a teenager, Lazarus did not know Hebrew yet. In one letter reproduced by Richard Gottheil, she asks his father to teach her the language. To remedy this problem, Gottheil sent her translations from other German rabbinic scholars, like Abraham Geiger’s works on Yehuda Halevi and Ibn Gabirol, and Michael Sachs’s anthology of religious poetry from the Jews in Spain.

Gottheil’s request opened a new door for creativity, a window into an ancestral past previously inaccessible to an earlier Sephardic poet like Grace Aguilar. Here, in the German, Lazarus discovered a wide spectrum of poetry written by her medieval Jewish forbearers: not only liturgical poetry, but wine songs, meditations on mortality, odes to friendships, eulogies, riddles, songs of Zion, and erotic poetry. Lazarus turned down Gottheil when he asked for more translations but would translate for herself more Hebrew Andalusian poems that she read in German and published them in Jewish periodicals starting in 1879. These translations became part of a collection of poems she published in 1882, called Songs of a Semite: The Dance to Death and other Poems.

Hymn 167 contains one such contribution by Lazarus. Gottheil selected a Yom Kippur poem by the eleventh-century Andalusian poet Moses Ibn Ezra, “In the Night,” originally called נַפְשִׁי אִוִּיתִיךָ בַּלַּיְלָה (“My soul yearns for You in the night”), which Lazarus read in Michael Sachs’s German translation. The original conforms to the Arabic genre mustajab, which Andalusian Jews adopted specifically for the Yom Kippur liturgy. Structured on four-line stanzas, the first three lines rhyme followed by a fourth line that always quotes a biblical verse and sets a sustained rhyme or word. In the Ibn Ezra poem, each stanza in the long poem closes with a biblical verse that ends with the word ‘night’ (nacht). In translating from Hebrew to German, Sachs retained the basic rhyme scheme as well as the emphasis on the word ‘night’, but ignored the biblical references interwoven throughout the poem, neither commenting on Ibn Ezra’s biblical sources nor following traditional German translations of biblical verse. The absence of this intertextuality eliminates the atmosphere embedded in the poem, creating new problems. For Gottheil’s hymnal, Lazarus only translated a number of stanzas from Sachs, but she wasn’t satisfied with her initial attempt. She would later return to the German source and translate the entire poem, as well as tweak earlier lines printed in the hymnal. In her final version, printed in her collection Songs of a Semite, the final stanza of Lazarus’s poem offers a window looking into the displacement between original context and a modern English rendering:

He speaks: My son, yea, I will send thee aid,

Bend thou thy steps to me, be not afraid.

No nearer friend than I am, hast thou made,

Possess thy soul in patience one more night. (80, l. 68-72))

The poem is a personal prayer charged with the speaker’s regrets in life and attempts at repentance and ends with God’s response. Lazarus offers a close translation of the German. Mein Kind becomes “my son,” Kein näh'rer Freund becomes “No nearer friend,” for example, but the original Hebrew, followed by my literal translation, offers a different image:

הִתְבַּשְׂרִי

, בִּתִּי

, כִּי עוֹד

אַנְחִילֵך חִנִּי

וּלְאַט אַנְחֵךְ

וְאַנִּיחֵךְ בִּמְעוֹנִי,

כִּי אֵין גּוֹאֵל קָרוֹב

מִמֶּנִּי —

לִינִי הַלָּיְלָה!

Hear, my daughter, I will yet pass on to you my affection

And slowly I will guide you and place you in my dwelling,

As there is no redeemer closer than I ––

Stay for the night! (Hebrew qtd. in Schirmann #170, p. 417)

Ibn Ezra’s original Hebrew borrows from one of the most ambiguous narrative scenes in the Hebrew Bible when Ruth, the widowed impoverished Moabite, visits Boaz in the middle of the night as he’s sleeping on the threshing floor and uncovers his feet to lie beside him. As Boaz is distantly related to her former husband, and since she has no children, he may legally redeem her by marrying her. He wakes up and indeed promises to marry her, so long as another potential redeemer, closer in the family, refuses the task. The mysterious and precarious scenario Ruth walks into offering herself to a man alone in the middle of the night, is charged with erotic strangeness or potential catastrophe, and the poet Moshe Ibn Ezra quotes from that scene as if to parallel one’s relationship with God to that of Boaz and Ruth. In the Hebrew poem, “my daughter” refers to a person’s individual soul or the collective Israel, but in Lazarus’s English translation, the stanza unambiguously suggests a paternal relationship. God is now like a father reassuring his son, a friend, whereas the original implies potential lovers, with the protection afforded by marriage.

If the poem underwent something of a textual diaspora of languages and cultures, traveling from medieval Spain to Germany to New York, so too does its music. Gottheil separately printed sheet music to go along with his hymnal, edited by Temple Emanu-El’s organist A. J. Davis. Like the poems inside, most of the music derives from non-Jewish sources. For the Lazarus poems, the melodies on the sheet music bear the names of nineteenth century English and German composers, like Philip Henry Diemer, organist for Trinity Church in Bedford, and Frederick Arthur Gore Ousley, organist for Hereford Cathedral. Although Davis did not cite the names of the original hymns, they become evident when scouring contemporaneous Christian hymnals. In the case presently discussed, the music for “In the Night” was lifted from the 1863 hymn “Dalkeith” by Thomas Hewlett, organist for various churches in Edinburgh, and a popular melody for Christian hymns. It appears, for example, as the transcribed melody for “Weary of earth and laden with my sin,” “Not what I am Lord, but what thou art,” and, three years after Gottheil’s edition, a hymn titled “Slain for my soul, for all my sins defamed.” These Christian hymns incorporate the same song of this modern Sephardic poem, itself an English translation of a German translation of a Hebrew Andalusian poem that conforms to the Arabic genre of the mustajab.

Rarely, however, Gottheil’s hymnal appropriated from an actual Jewish melody. In addition to her three Andalusian poems, and notwithstanding her religious demurrals, Lazarus composed a poem that does not appear in the multiple collected works published after her death, a rewriting of the final chapter of Ecclesiastes:

Remember Him, the only One,

Now, e’er the years flow by;

Now, while the smile is on thy lip,

The light within thine eye;

Now, e’er for thee the sun have lost

Its glory and its light;

Or earth rejoice thee not with flowers,

Nor with its stars the night.

Now, while thou lovest all on earth,

And deemest all will last,

Before thy hope has vanished quite,

And every joy has past,—

Remember Him, the only One,

Before the days draw nigh,

When thou shalt have no joy in them,

And, praying, yearn to die. (qtd. in Gottheil 46-47)

Fig.9 - Sheet music of Lazarus’s “Remember Him.” in A. J. Davis’s Music to Hymns and Anthems, 1887, 41.

In the accompanying music book, Davis included two different melodic interpretations for the poem. The first derives from a song by the German composer Louis Spohr. Perhaps because Lazarus was what Gottheil called a “gifted poetess of Sephardic stock,” Davis included a second melody (see Figure 9), a “Traditional Sefardic Tune arranged by G. S. Ensel.” (R. Gottheil 61; Davis 41) Like Gottheil, the Bavarian choirmaster Gustav S. Ensel had lofty visions of incorporating classical, non-Jewish music to create an enlightened Jewish American identity. But Ensel didn’t compose music, so I searched for an original source and found that the melody derives from The Ancient Melodies of the Liturgy of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews, printed in 1857 and compiled in London by Rabbi David De Sola with music transcribed by none other than Emanuel Aguilar. Once again, the Sephardic composer assisted in preserving a collection of texts through the printing of music notation. As the introduction to Ancient Melodies notes, De Sola selected old melodies he learned in Amsterdam, which Aguilar “harmonized so as to be sung in parts…written in the manner…thought most convenient for playing” (E. Aguilar). Lazarus’s Ecclesiastes poem, layered in four-part harmony, originally applied to a song at the end of Shabbat composed by the twelfth-century French Rabbi Jacob of Lunel, titled “Bemotsae Yom Menucha” in Ancient Melodies (see Figure 10).

Fig.10 - Original source for Lazarus’s Ecclesiastes hymn, “Remember Him,” in De Sola’s Ancient Melodies, 1857, 22.

The melody to the medieval Hebrew song is not commonly sung among the Western Spanish and Portuguese communities, nor has “Remember Him” been preserved in any American prayer book after Gottheil’s attempts to codify a new American liturgy. Interestingly, however, the melody, like those repurposed Christian hymns, has been appropriated by Ashkenazi communities around the world and used today when returning Torah scrolls back to a synagogue’s ark on Shabbat as a song from the biblical passage of Lamentations (5:21):

הֲשִׁיבֵנוּ ה'

אֵלֶיךָ

וְנָשׁוּבָה חַדֵּשׁ יָמֵינוּ כְּקֶדֶם

Bring us back to You, Lord, that we come back, renew our days as of old.

New texts revive old sounds in the global Sephardic diaspora. The passage elucidates the creative projects of Grace Aguilar, Penina Moïse, and Emma Lazarus, Jewish poets who composed new texts by imagining or with the assistance of old sounds. The dream of a homeland, whether a lost medieval Spain or the ideals of a modern America or England illustrates the complex ways in which a Sephardic diaspora incorporates a global landscape of accompanying music.

Works Cited

Aguilar, Grace. “History of the Jews in England.” Grace Aguilar: Selected Writings, edited by Michael Galchinsky. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview, 2003, pp. 313-353.

---. “Song of the Spanish Jews, During ‘Their Golden Age.’” The Occident and American Jewish Advocate, vol. 1, no. 6, 1 September 1843, pp. 289-290.

Aguilar, Grace, lyricist. “Edith: A Song of the Eleventh Century for Voice and Piano, Op. 13.” Composed by Emanuel Aguilar. London, Wessel and Co., 1851, British Library.

Aguilar, Emanuel. Editing note to The Ancient Melodies of the Liturgy of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews by D. A. De Sola. London, Wessel and Co., 1857, p. 25.

Davis, A. J., composer and editor. Music to Hymns and Anthems for Jewish Worship by Dr. G. Gottheil. New York, N.P., 1887.

De Sola, D. A. The Ancient Melodies of the Liturgy of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews. London, Wessel and Co., 1857.

Harby, Lee C. “Penina Moïse, Woman and Writer.” The American Jewish Year Book, vol. 7, 1906, pp. 17-31.

Gottheil, Gustav, editor. Hymns and Anthems Adapted for Jewish Worship. New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1887.

Gottheil, Richard. The Life of Gustav Gottheil: Memoir of a Priest in Israel. Williamsport, PA: Baynard, 1936.

Lazarus, Emma. Songs of a Semite: The Dance to Death, and Other Poems. New York, The American Hebrew Publishing Company, 1882.

Moïse, Penina. Secular and Religious Works of Penina Moïse, with Brief Sketch of Her Life.

Compiled by Charleston Section Council of Jewish Women, Charleston, SC: Nicholas G. Duffy, 1911.

Murdoch, James Edward. Patriotism in Poetry and Prose: Being Selected Passages from Lectures and Patriotic Readings. Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1865.

Murdoch, James E. and Robert Burns. “The Hurrah for ‘The Red White & Blue’: ‘An Old Friend in a New Dress:’ Lines by Robert Burns, altered and adapted to suit the present times by James E. Murdoch.” Cincinnati, John Church, Jr., 1864, Library of Congress.

Rosen, Robert N. The Jewish Confederates. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2000.

Schirmann, Jefim. Ha-shirah ha-‘ivrit bi-sefarad u-ve-provans [The Hebrew Poetry of Spain and Provence]. 1954. Vol. 2, Jerusalem: Mossad Bialik, 1960.

1 Leonard Stein is a literary scholar, musician, and writer. He received his PhD at the University of Toronto Centre for Comparative Literature and Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies. He researches and lectures on Sephardic literature, early Modern English literature, and the intersections between music and literature. He also composes music to medieval Jewish poetry.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800