David Ohana

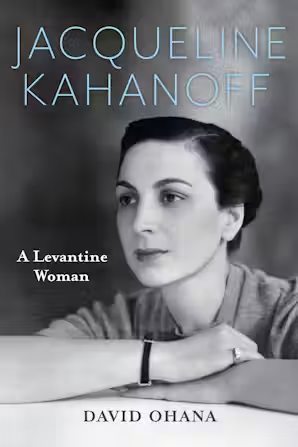

JACQUELINE KAHANOFF: A LEVANTINE WOMAN

Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2023. ISBN: 978-0253066886

Reviewed by Aimée Israel-Pelletier1

David Ohana's book is an intellectual biography of Jacqueline Kahanoff who is best known today in academic circles for her reflections on the Mizrahi condition in modern Israel and for rebranding the term Levantine to advance a politics of coexistence that she saw as crucial for Israel's survival in the region. She is also viewed by non-academic types as an activist and a feminist, helping to advance the cause of both Mizrahi Jews and women. Ohana's book goes through this terrain and beyond it, fleshing out Kahanoff's portrait with significant details.

We learn, for example, that in addition to her celebrated novel, Jacob's Ladder,2 several short stories, and many essays, Kahanoff wrote poetry. The eight poems Ohana uncovered in the Gnazim Archives of the Hebrew Writer's Association in Tel Aviv and included in their entirety in this book are certain to contribute depth to discussions of Levantine aesthetics. He has also found drawings and many unpublished essays, articles, and book reviews. For those who do not know Hebrew and for those who do not have access to the archives, Ohana's book represents a valuable trove of information. It promises to open wide the field of Kahanoff and Levantine studies.

Kahanoff has written a great deal and her topics are numerous and varied. This was a revelation to me. Ohana has given us an entry unto unpublished essays, articles, and a voluminous correspondence from the Gnazim Archives and from the Heksherim Institute at Ben-Gurion University. The task Ohana has undertaken is huge. It comes at a time when a more complete picture of Kahanoff is required, if only because, more and more, Kahanoff has taken on the proportions of a legend. As Ohana relates:

Her works are studied in universities; articles are written about her in academic journals in Israel and elsewhere; her essays are included in school curricula [...] In Israel, a school and a street have been named after her, and a Hebrew children's book presents her literary portrait. There have been radio programs about her and a film in the documentary series The Hebrews; in addition, the Eretz-Israel Museum in Tel Aviv devoted an exhibit to Kahanoff's life and works (p. ix).

Besides the letters, poems, and drawings he has uncovered, Ohana's dive into the archives brings together texts in their "prepublication version," articles scattered in various newspapers and magazines, interviews, book reviews, and more. He summarizes many of the unpublished texts and brings out telling information, helping to round out the figure of the writer, her perceptions, and others' perceptions of her. Kahanoff writes insightfully about education, society, music, film, tourism, aging, and much more. We learn, for example, that Kahanoff found inspiration in the Essays of the sixteenth century Montaigne, that she admired, and was inspired by the work of her contemporary Susan Sontag, and that she corresponded with the poet Dahlia Ravikovitch. Ohana includes the letter in which the latter, a younger, recognized poet and a Sabra, fascinated by Kahanoff, asks for guidance on how to think about Israel, that is, how to process what she was living through. For Ravikovitch, and other writers, artists, and intellectuals, Kahanoff represented an opening to the wider world outside Israel. As A. B. Yehoshua writes, "Within the crystalizing Israeli identity, she opened a window for us on worlds with which we were not familiar; not Mizrahi folklore but the intellectual Levant (p. 164)."

Kahanoff did not write in Hebrew. She relied on translations into that language to communicate to an Israeli audience. We learn that Aharon Amir, who translated Kahanoff's texts into Hebrew, took liberties with some of her work. In certain instances, he even omitted passages she had written. For example, he omitted the following critical reference to Darwin, a writer who "aroused the most resentment in her":

If Darwin were right, then the Nazis were right. There was a master race, and when it had destroyed all mankind, it could only destroy itself. The last man would die, triumphantly asserting his domination over the devastated earth (p. 141).

Ohana points out some unfortunate translations, as for example, translating the title of the essay "Ambivalent Levantine" into "Black on White (p. 142)."

Ohana explains that Kahanoff wrote about the European intellectual scene but that she also wrote extensively about the literatures and cultures of Africa, the Caribbean, and Japan in essays, book reviews, and anthologies. In two chapters, he delves into these areas and summarizes many of Kahanoff's texts. In her anthology of African literature, he describes her command of various materials, texts written in both English (discussions of South Africa's Peter Abrahams and Can Themba) and French (David Diop, Leopold Senghor, Camara Laye, Aimé Césaire, and many others). He reviews her in-depth studies of Charles Péguy and Claude Vigée, and others too numerous to mention. In her review of Quatre lectures talmudiques by Emmanuel Levinas, Kahanoff proposes an alternative conclusion to his notion of a "post-Christian Judaism (p.191)." While Levinas argued that post-Holocaust Judaism needed to connect with Christianity on a new footing, Kahanoff argued that, more importantly, Judaism needed to forge a "post-Islamic Judaism," a narrative "to reckon with the fact that the rebirth of Israel in modern times has shaken the Islamic world to its foundation," making it essential for Judaism to "create a connection with it through an open debate on its tradition (p. 191)."

Kahanoff's knowledge of both European and non-European literatures, cultures, and ideas is impressive. For Ohana, she is a "theoretician of culture" who developed "a universal model" to understand cultural production created at the points of intersection between cultures and languages, tradition, and modernity. She replaced the model of a "national" literature by, in Kahanoff’s words, a "literature of mutation (p. 184).” A distinguished literary and cultural critic, she read widely, commented perceptively, and was, as he puts it, "groundbreaking," discussing the complexities of multiculturalism decades before they were taken up by Postmodern critics (p. 184). Ohana's study opens a rich terrain for exploring Kahanoff's views on her perspective on African American humanism. She reflected, wrote, and lectured on literature, film, art, music, education, on existential issues, on Judaism, and on Israel. Her articles on Levinas, Judaism, and Zionism are worthy of considered attention. Her entire large and significant production, Ohana shows, reflects a commanding understanding of the political, social, and cultural landscape of Israel and the contemporary world. She was in the fullest sense of the word a twentieth century intellectual.

In the chapter he devotes to Levantinism and in his Epilogue, Ohana lays out the various viewpoints writers and scholars have attached to the term and how the concept of Levantinism both competes with and completes the idea of a Mediterranean Israel. He concludes, rightly I would add, that Kahanoff's theory of Levantinism is a "mythic narrative in support of an idyllic image of Levantinism to inspire Israel to affirm a Mediterranean Levant identity (p. 124)." For Kahanoff, the Levant is not an abstract concept. It is a way of seeing the world. She wrote in a "projected book" in English of her collected essays that Levantinism has a "mythical dimension," conceptualized as a kaleidoscope of cultures revealing different perspectives over space and time. Kahanoff's Levantinism, I have written elsewhere, is an aesthetic. It is an approach, a creative construct, to manage the demands and desires of a diverse society in such ways as to encourage minorities to coexist while retaining their individual identities, cultural and religious.3 Jacob's Ladder, a novelistic coup de force, illustrates how Levantinism works, what it looks like on the ground, and how it succeeds. Levantinism is a humanism, a concept-tool, and, above all, a practice.

David Ohana's study of Jacqueline Kahanoff contributes immensely to our understanding of the breadth and depth of her work and to the Levantine ambition that undergirds it. It invites us to engage with that corpus and to celebrate it as if the future of Israel and of the global order depended on it.

1 Aimée Israel-Pelletier is professor of French at the University of Texas at Arlington. She is the author of On the Mediterranean and the Nile: The Jews of Egypt. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2018) and books and articles on French Literature, art, and film. She has written on Memmi, Jabès, Flaubert, Rimbaud, Impressionism, and Rohmer.

2 Jacqueline Shohet, Jacob’s Ladder, (London: Harvill, 1951).

3 See the chapter "Jacqueline Kahanoff's Egypt: A View From The Nile" in On the Mediterranean and the Nile: The Jews of Egypt (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2018).

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800