Debby Koren

Responsa in a Historical Context

A View of Post-Expulsion Spanish-Portuguese Jewish Communities

through Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Responsa

(Studies in Orthodox Judaism)

Newton, Massachusetts: Academic Studies Press, 2024, ISBN: 979-888719-3595

Reviewed by Andrew Apostolou1

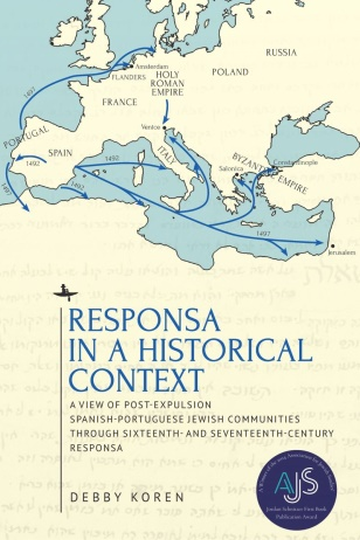

The expulsion of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula in 1492 and 1497 was the greatest catastrophe in Jewish history between the Bar Kokhba revolt (132-135 CE) and the Khmelnytsky massacres (1648-1656). The massive eviction of Iberian Jews ended cultural life and religious study that had been productive for Jews and Muslims alike. The kingdoms of Castile and Aragon pushed out an estimated 200,000 Jews in 1492.2 Portugal ejected the Jews in 1497. Many remained in these countries by converting to Christianity. Portuguese Muslims, also forced to leave by King Manuel I in 1497, did not receive the option to become Christians.

These sudden emigrations devastated the personal and communal lives of Iberian Jews. Many died en route to North Africa, Italy, or the East Mediterranean.3 Others stayed put, for a while. Some of them maintained as much Jewish practice as safely permitted. We cannot know how many managed to do so, or for how long. Even the suspicion of residual Jewish identity could be fatal for years, or centuries, after the expulsion. In 1506, gangs of foreign sailors and “Old Christians” in Lisbon massacred those they believed to be “New Christians” (recently converted Jews or conversos).4 In 1720, the Spanish authorities garroted a monk, Fray Joseph Diaz Pimiento (aka Abraham) in Seville for Judaizing.5 The same year they apprehended a small Jewish community in Madrid. These Jews had been operating a secret synagogue in the Spanish capital since 1707. They even had selected a rabbi in 1714. The secular authorities executed five of them. The last inquisition for the crime of “Judaizing” was in Córdoba in 1818.6

Debby Koren’s book deals with the religious consequences of this persecution for Iberian Jews. The book examines eight different responsa (answers to questions about Jewish law, teshuvot in Hebrew), most from prominent Sephardic rabbis. She lays out her approach in a short introduction. Responsa in a Historical Context is not a compendium of historical sources that examines the daily lives of conversos. Rather, Koren elaborates how the rabbis solved religious problems. As Koren observes, we should value Sephardic culture for its learning as well as its food and song. Her volume won the AJS Jordan Schnitzer First Book Publication Award.

Before analyzing each responsum, Koren provides a brief introduction to excommunication in Sephardic halacha (Jewish law). The practices of niddui (shunning) and herem (cutting people off from the community) were important sanctions for post-expulsion Sephardim. They are suggested as punishments in some of the responsa. The best-known example was the herem against Baruch Spinoza in Amsterdam in 1656. Although some treat Spinoza as a pioneer of modernity,7 others regard him as an anti-hero who spurned Jews and defamed Judaism.8 Spinoza has become part of the continuing, and irresolvable, question of when and where Jewish modernity began. Generally, Koren avoids these larger historiographical issues.

Koren first describes the historical context for each ruling. Then she introduces the halachic issues. The main sources are in English-Hebrew parallel text. She provides accurate translations. After discussing the halachic background, Koren presents the actual responsum, again with a strong translation. Throughout there are supporting footnotes. There is a brief summary of the responsum, followed by “Questions for Further Discussion.” Although such questions may not concern historians, they bring the halacha to life, connecting it to contemporary problems.

Most of the eight responsa are historically significant, with a detailed review below. The exceptions are the seventh and eighth. These relate to conflict in the Amsterdam community and the insertion of the prayer for rain south of the Equator.

The first responsum concerns a woman, Hanna, who sought the ability to remarry after her husband and her get (bill of divorce) vanished. Her husband, whose name is lost, had embarked upon a journey before the expulsions. What is unusual is that the divorce originated in spousal kindness, not matrimonial acrimony. The husband sent Hanna, probably a pseudonym, a get which allowed her to marry again should he not return within four years. Hanna arrived in Jerusalem after the Iberian exodus, but less than four years after receiving her get. To aggravate matters, she lost her get while fleeing, depriving her of documentary proof of her status as a divorced woman.

The reponsum captures Hanna’s conversations and social interactions. She feared gossip in the marketplace if people believed she were single. The rabbis in Iberia and Jerusalem addressed her as “עניה עניה” (“you poor thing, you poor thing”). Rabbi David ben Solomon ibn Abi Zimra (Radbaz, Spain 1479-Tzfat 1573) decided that the divorce was valid; Hanna could remarry. There was rabbinic discussion of granting such pre-emptive divorces during World War II, but Koren relegates this instance to a footnote.

The second responsum concerns the bribes Jewish communities offered to reduce taxes. The fabled protection that the Ottoman Empire extended to the Jews came at a price. The initial welcome waned under Murad III (1574-1595). The empire reached its territorial apex under his rule, and placed greater imposts on the Jews. Reuben, probably another pseudonym, approached the sultan to cancel customs duties that affected the Jews. He appears to have acted on his own initiative. Leading figures in the community offered to pay Reuben for his considerable expenses should he succeed. However, after some back and forth with corrupt viziers, the community sent another man, Simeon, again likely a pseudonym, to obtain resolution. Reuben nonetheless claimed his fee and argued that he had succeeded.

Rabbi Joseph ibn Lev (Mahari ibn Lev, Monastir 1505-Constantinople 1580) decided that the community leaders had to pay Reuben. He avoided ruling on Reuben’s claimed achievement, instead encouraging the disputing parties to agree.

The third responsum concerns a charge of heresy against a man for studying non-Jewish science. The question related to the longstanding controversy over whether Jews should engage in so-called Greek wisdom. As Koren observes, the two issues are the nature of Jewish engagement with non-Jewish learning and the Jewish requirement of Torah study. Reuben claimed that Simeon did not worship the God of Abraham and Isaac but “the god of Aristotle.” He also termed Simeon a מין (min) and an אפיקורוס(apikores, heretic). Koren translates מין as apostate. She could also have used “sectarian.” The latter possibility may apply as there was still a Karaite community in Constantinople at the time.

Rabbi Elijah ben Benjamin Ha-Levi (Constantinople 1481-after 1540) defended Simeon with fury. He called Reuben “a sinner and a dimwit, and a defamer is a fool (Prov. 10:18).” In his responsum, Ha-Levi observed that Reuben was smearing such great rabbis as the Geonim and Moshe ben Maimon (Maimonides, Spain 1138-Egypt 1204). Maimonides had influenced scholars of other religions with his argument for the existence of God. Rabbi Ha-Levi was from the Greek-speaking (Romaniote) community in Constantinople. Romaniotes had defined Judaism in the Mediterranean for a considerable part of the first millennium of the common era. They even conducted much of the synagogue service in Greek.9 At the time of the responsum, the Romaniotes remained a significant community, but their influence was ebbing with the influx of Iberian Jews.

The fourth responsum concerns the impact of religious division on family ties and inheritance. Conversos and their Jewish family had maintained relations before the expulsion.10 That ended after 1492. In this case, a father left property to his Jewish son unconditionally. He promised his two other sons, who were “New Christians,” their share on condition they left Spain and worshipped again as Jews. One “New Christian” son made the journey, but declined to return to Judaism. His mother nonetheless gave him his inheritance. The Jewish brother objected.

Rabbi Moses ben Joseph di Trani (Mabit, Saloniki 1500-Tzfat 1580) ruled for the Jewish son. Still, he held out the possibility of an inheritance to the “New Christian” son who had remained in Spain should he become a Jew again.

The fifth responsum concerns whether Jews can have non-Jewish names. Portuguese conversos took Hebrew names when they returned to Judaism. However, when dealing with business and family in Portugal they used their previous Christian names. That created the concern that their embrace of the Torah might not be genuine. Rabbi Samuel de Medina (RaShDaM, Saloniki 1505-1589) dismissed the concern quickly. Although a halachically simple issue, Koren could have enlivened her discussion with well-known name changes in the Torah (Abram became Abraham, Sarai became Sara) and likely non-Jewish names (Moshe, Ephraim, and Menashe).

The sixth responsum concerns an accusation that a forced convert saved himself by informing on others. Filippo de Nis (later Salomon Marcus), was a Portuguese “New Christian,” baptized in infancy. Another “New Christian,” Maria Lopes, betrayed her father and stepmother’s secret Jewish practices. While doing so she mentioned that de Nis kept the Sabbath and other customs. A priest then told the Venetian Inquisition that de Nis, who lived in Venice, was Judaizing. In response, de Nis initially claimed to be a Jew. That story did not hold up. He then explained his adult circumcision as having been done by a Jewish doctor, Benarogios, who treated him while he was ill. de Nis also mentioned another Jew who had circumcised his nephew. Eventually, he proclaimed himself penitent courtesy of divine intervention. de Nis went to prison and renounced his Judaism. A few years later de Nis fled East and restarted Jewish observance.

The question for Rabbi Solomon ben Abraham Ha-Kohen (Maharshak, Saloniki circa 1520-circa1601) was whether de Nis should pay damages for informing. Benarogios had to flee Venice, losing everything. Apparently, the Venetians captured Benarogios’ wife and children, who then left Judaism, although there were no witnesses for these claims. The Maharshak compromised. He ruled against compensation because the harm was indirect. However, the rabbi felt that de Nis’ conduct was worthy of teshuva (atonement), during which he should pacify Benarogios with some money.

Unfortunately, Koren does not provide a conclusion for her book. That is a missed opportunity to connect this volume to wider issues about conversos, halacha, and the history of how the Spanish and Portuguese Jews rebuilt their lives and their communities. The expellees utterly changed Jewish practice throughout the Mediterranean, from Morocco to Syria. Many of those left behind took generations to become Jews again, but return they did. They established Jewish life in the Low Countries, England, and the Americas. That may not have been the spark of modernity. It was, without doubt, a renaissance of culture and learning that only the modern persecutions of the twentieth century would extinguish.

1 Andrew Apostolou is a historian of the Holocaust in Greece and a writer on contemporary Jewish affairs. Dedicated to the memory of Laurent Chichportiche (1965-2024) z"l.

2 Haim Beinart, The Expulsion of the Jews from Spain (translated by Jeffrey M. Green) Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. Liverpool University Press; 2001, page 290.

3 Marx, Alexander. “The Expulsion of the Jews from Spain.” The Jewish Quarterly Review, vol. 20, no. 2, 1908, pp. 240–71. JSTOR.

4 Yerushalmi, Yosef Hayim. The Lisbon Massacre of 1506 and the Royal Image in the Shebet Yehudah. Hebrew Union College Press, 1976. JSTOR. Soyer, François, “The Massacre of the New Christians of Lisbon in 1506: A New Eyewitness Account.” Cadernos de Estudos Sefarditas, n.º 7, 2007, pp. 221-244.

5 Gottheil, Richard. “FRAY JOSEPH DIAZ PIMIENTA, ALIAS ABRAHAM DIAZ PIMIENTA, AND THE AUTO-DE-FÉ HELD AT SEVILLE, JULY 25, 1720.” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, no. 9, 1901, pp. 19–28. JSTOR.

6 Henry Charles Lea, A History of the Inquisition of Spain, Vol. III. London, Macmillan, 1907, pp.308-311.

7 Rebecca Goldstein, Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity. Nextbooks/Schocken; 2006.

8 José Faur, In the Shadow of History: Jews and Conversos at the Dawn of Modernity Albany, New York: SUNY Press, 1991, chapter 8.

9 Nicholas Robert Michael De Lange, Jews in the Byzantine Empire. Editor, Robert K. Pitt. Athens, The Jewish Museum of Greece, 2022, chapter 4.

10 Dora Zsom, Conversos in the Responsa of Sephardic Halakhic Authorities in the 15th Century, Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2014.