Alfred Ascher

Introduction and translation by Gloria J. Ascher

THE DIARIO

THE DARING ESCAPE OF TWO SEPHARDIC JEWS FROM TURKEY TO AMERICA DURING WORLD WAR I

Boulder, Colorado: Albion-Andalus, 2023, ISBN: 978-1-953220-29-5

Reviewed by Canan Bolel1

One of the most anticipated Sephardic Studies books of 2023 for me was The Diario, Gloria Ascher’s English translation of Alfred Ascher’s diary, which was originally written in Ladino in 1915. This thin volume chronicles the mis/adventure(s) of Alfred and his brother Albert following their escape from their hometown Izmir (Smyrna) with the further escalation of World War I. In this journey although they had plans of returning to their city and family, they find themselves, somewhat accidentally, in New York. A single story among many from 1915, perhaps one of the most turbulent periods of the war filled with outbreaks of systematic violence, comes back to life through the lens of a young Sephardic man. It helps us to understand the role of the unpredictability of life and luck, something we tend to overlook as we piece together historical narratives. Moreover, it shows us an individual’s success in writing himself into history through his diary as an act of resistance to a life destined to be forgotten, an experience to be erased.

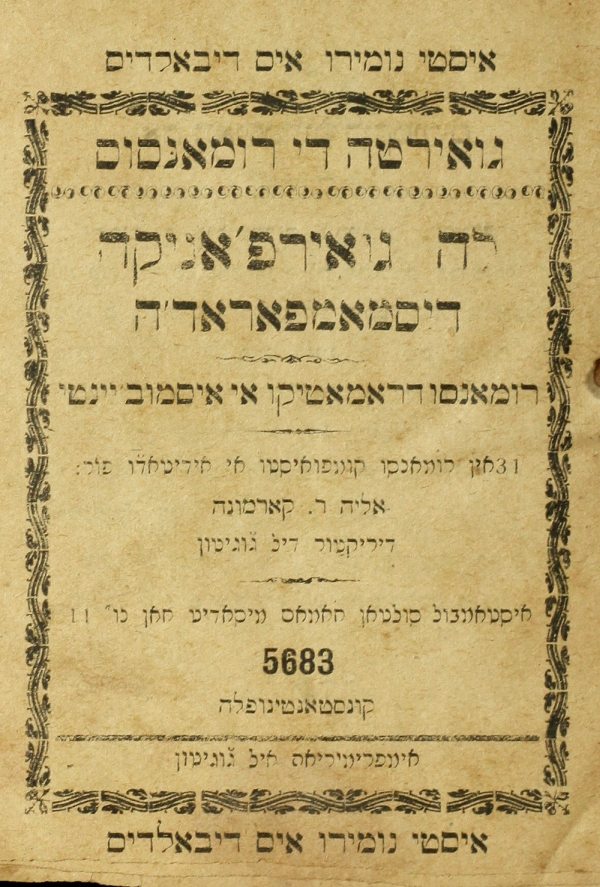

In two parts, The Diario covers the Ascher brothers’ five-month journey through twelve locations, including small Aegean islands, Greek port cities, Algiers, and finally, New York. Thanks to the reproduction of several original pages in the book, one can get a glimpse of Alfred’s idea for his diary, which constantly moves back and forth between a confidant, a letter to be read aloud in a close family gathering, or a serialized novel in the Sephardic tradition (romanso) to be enjoyed by the public.2 Considering the popularity of romansos during this period, it is not surprising that Alfred imagined himself as a young, brave, and witty protagonist with side figures such as the Greek bandit, the ruthless Turkish soldier, and the reasoned French consul. The influence can be traced to the diary’s title page, which Alfred created himself, embellished with his deliberately composed handwriting to create the illusion of different fonts for the title and the tagline. He made sure to include the tagline “İNOLVİDALVES İ ESMOVİENTES PASSAJES (Unforgettable and Moving Passages).” This promotional line can be seen in some works published in 1900s while becoming an indispensable feature of Ladino fiction, including translations, adaptations, and original works, of 1920s and 1930s. It promised excitement, tears, and a brief escape from reality.

The title page of La Guerfanika Desmamparada [Romanso Dramatiko i Esmoviente] by Elia R.

Karmona, published in 1922/3 in Istanbul. Sephardic Studies Collection, University of Washington, ST00386.

Throughout their journey, luck was on the side of the Izmirli brothers. They were able to move without being noticed by Turkish soldiers, were able to find figs and grapes when they were starving, they met with a fellow Izmirli in a cafe and later a Jewish man from Salonica who sowed the seed of Amerika in their mind in a restaurant. Once they arrived at Castle Garden in one piece and passed the inspection at Ellis Island, they found themselves on the other side of the ocean and the world. Along with this chain of unforeseen blessings, Alfred and Albert took advantage of something more tangible: papers identifying them as French subjects.

'We are Frenchmen', said Alfred and Albert at every opportunity”(44). Sephardic Jews’ experiments and experiences with modern passport rules and regulations have been studied by Sarah Abrevaya Stein in Extraterritorial Dreams (University of Chicago Press, 2016) and Devi Mays in Forging Ties, Forging Passports (Stanford University Press, 2020). With all its rawness, The Diario emerges as the perfect companion to these monographs, which involve the constant passing of papers, language switching, money constantly changing hands, and lies being told while the brothers never ceased to embody the image and the ideal of an imagined Frenchman. For instance, amidst everything, the first thing the brothers did once they landed at Mytilene was to find a barber and get their now long and knotted beards shaved.

Dina Danon’s The Jews of Ottoman Izmir (Stanford University Press, 2020) is the book that guides us through the multiple layers and complexities of the late Ottoman (Jewish) Izmir, the world in which Alfred and his brother grew up in the 1890s. The Diario, through Alfred’s fears and desires also complicates the interpretations of Sephardic family that shape our writings of the modern Sephardic experience. Here, the fluid nature of family reveals itself through the close alliances the brothers formed on the road, families they created with individuals with different upbringings, and, of course, being a family (or not) while living on different continents and not seeing one another for years, even decades. Bringing the diary back to life paved the way for forming another family. As Gloria Ascher wrote, “Ke todos ke lo meldan se agan famiya! (May all become family who read this treasure!).” It is apparent that in the making of the book, Gloria Ascher created a family of community members, students, scholars, Ladino enthusiasts, and the readers, through their shared interest in a peculiar personal journey.

The Diario is also valuable teaching material for those who teach courses centered around modern Jewish histories and cultures. The Introduction alone is a comprehensive record of efforts centered on sparking interest in, and reintroducing Ladino into daily life, ranging from university courses to a popular Netflix show and from online forums to international events. Lastly, this bilingual edition with the Ladino original and English translation side-by-side, is an excellent resource for beginning Ladino learners. It is a valuable text for those with advanced skills to trace the nuances of the language.

The new life in Amerika is described in just a few paragraphs right before the finale, as if a place to live, a job, and a wife appeared out of the blue in the blink of an eye. Alfred ends his modest attempt at recording an already fleeting and disappearing world by writing, “I give a thousand thanks to God and to the United States – I can say that they saved my life.” (77) Between the lines and also through more explicit statements such as “the Barbarous Turk,” Alfred hints that their journey in 1915 was not only one of adventure. Were they only escaping the war or a possible nightmare they believed the “Barbarous Turk,” in Alfred’s words, was capable of doing? What were they so afraid of?

Despite its few pages, The Diario is a precious crumb of a lived reality from the Ottoman Empire’s final years full of ambiguity and fear, and readers are left with many questions; perhaps some of the answers have already gone with the Ascher brothers.

1 Canan Bolel is an Assistant Professor in Jewish Cultures, Languages, and Literatures of the Eastern Mediterranean in the Department of Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures at the University of Washington. Her current book project focuses on marginalized individuals and groups in the Jewish community of Izmir. Bolel received her Ph.D. in Near and Middle Eastern Studies from the University of Washington in 2022. She holds a Master of Sciences in Sociology from the London School of Economics and Political Science.

2 For more information on romansos see, Olga Borovaya, Modern Ladino Culture: Press, Belles Lettres, and Theater in the Late Ottoman Empire (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2012).

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800