Josh Tuininga

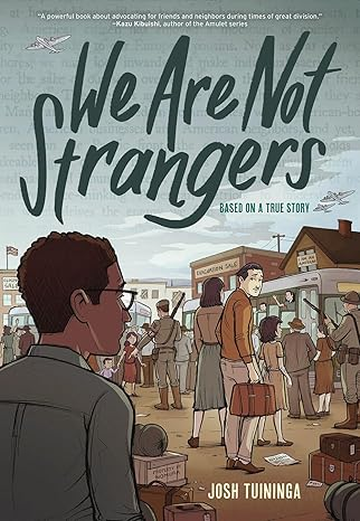

We Are Not Strangers

Based on a True Story

New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2023, ISBN: 978-141975

Reviewed by Annette B. Fromm1

Two families, two peoples, two travesties. Josh Tuininga captures the very personal aspects of these stories in his beautifully drawn graphic novel We Are Not Strangers. His illustrated narrative captures the intimate aspects of the stories of two peoples, two families tied together by ironically similar circumstances. They found themselves in unimaginable, unjust situations when all that they held dear and owned was lost when they were exiled simply because of their ethnic identities, something for which they were not responsible.

The first story, a much older tale, is that of the author’s ancestors who were expelled from medieval Spain and sent to the four corners of the earth by the edict known as the Alhambra Decree of 1492. Like many other Spanish Jews, his family settled in the Ottoman Empire. His grandparents, after many lifetimes there, once again were uprooted because of political and economic reasons. His grandfather crossed the Atlantic to finally find himself in Seattle, Washington at the western end of a vast continent. There he made a new home and established himself along with other members of a small but significant Sephardic community.

The second story is about members of Seattle’s Japanese community, many foreign-born who had been denied access to American citizenship and their children and grandchildren. The latter were born in the United States and, thus, were citizens. This was a prosperous community that contributed to Seattle in many ways. A life-long friendship was forged between the author’s Sephardic grandfather and a young Japanese-American man. It grew out of a business relationship of two minority people in a new country.

Both families, both peoples were affected by World War II. Readers learn that the author’s great-grandmother was able to escape the grip of the Nazis and join the separated family that had preceded her in Seattle. His friend’s family was not so lucky; like hundreds of thousands of Japanese Americans, they were interned in locations inland, away from the fighting in the Pacific. They were sent to inhuman camps across the American west, where they were held until the end of the war. They also lost much of their property and businesses at the same time.

Readers are drawn into World War II and the two families, the two peoples. We learn how each was affected by political policies that rocked the world. Readers see that the author’s grandfather regularly and avidly read about the unbelievable situation of Europe’s Jews. Readers also follow the unexpected fate of his Japanese-American friend, who with family members and neighbors are removed from their established Seattle homes and sent to incarceration camps.

Readers then learn the extent to which the author’s grandfather went to cement their friendship and, at the same time, relationships with other members of Seattle’s Japanese-American community. Embedded in this narrative, is tzedakah, the unique Jewish ethical value. It was always impressed upon me that anonymity is the essence of tzedakah; the identities of the donors and the recipients should not be public knowledge. Neither pride nor shame should be felt by either. While this word and the act has been equated with the Western value of charity, it actually refers to the religious obligation to do what is right and just. I would rather not be a spoiler, but invite everyone to read this book that documents a significant era of American history, that should never be forgotten, and the work of the author’s grandfather. It is also an important record of bravery of a Sephardic Jew who, like many others, carried his own family’s history close to the chest.

Throughout the text, the author offers glimpses into his grandparent’s home, rich in references to their Sephardic heritage through the use of Judeo-Spanish and the delicious persistence of traditional foods, prepared in Seattle Sephardic homes even today.

We Are Not Strangers, by virtue of its format, a graphic novel, is an easy read. Because of the relevance and strength of the personal story, it is a must read for all ages. Moreover, the poignantly told narrative draws the reader in seeking to learn the mystery held in its depths. It should be read to learn about the lengths to which true friendship can go. The age-old trials of the Sephardic Jews are relived in the twentieth century and the experiences many Japanese-Americans faced across the country during the Second World War.

I would love to see Josh Tuininga tackle the story of his family, of his people next. Perhaps he can put the tales of the many Sephardic Jews, including his own family, who exiled from the Iberian Peninsula made new homes in another empire in the Eastern Mediterranean and then, hundreds of years later crossed many miles to North America, to establish new homes in the frontier city of Seattle. He is a talented verbal and visual story-teller; this is a rich narrative that would hold up well to the format of a graphic novel. It would also be a worthy contribution to the growing literature of the Sephardic Jews of America.

1 Annette B. Fromm is the review editor and associate editor of Sephardic Horizons. Her research has focused on the Jewish community of Ioannina, Greece.