Judah ha-Levi ben Isaac ibn Shabbetai

His Medieval Jewish Satires1

By Marvin J. Heller2

Vast floods cannot quench love, nor rivers drown it. . . .

O you who linger in the garden,

A lover is listening;

Let me hear your voice

( Song of Songs 8:7,13)

Cursed is he who brings a woman into his house.

Every trouble has a remedy. Every misfortune a limit

But a married man is lost forever

(Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim)

R. Judah ha-Levi ben Isaac ibn Shabbetai (12th-13th cent.) was the author of three published popular parodies, albeit not all in his lifetime. Among them, indeed the most reproduced of the three, is a reputed misogynist work entitled Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim (The Gift of Judah the Misogynist). Minhat Yehudah, as the title suggests, is a satire about women. Ibn Shabbetai’s other satires are Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher (Strife of Wisdom and Wealth), a humorous dialogue about the merits of wisdom and wealth, and Divrei ha-Alah ve-ha-Niddui (The Words of the Curse and the Ban), a response to five prominent men of Saragossa, named in the manuscript, who had destroyed another of Shabbetai’s works. The first editions of Shabbetai’s works, noted below in more detail, were Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim and Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher, printed in Constantinople in c. 1543, and Divrei ha-Alah ve-ha-Niddui, first published in 1909 in Ha-Eshkol.

Shabbetai is a somewhat enigmatic figure. His life was unsettled, wandering from place to place. Born in either Toledo or Burgos, in Aragon, Spain, in about 1188, he was resident in Toledo and Saragossa, all significant cities of the Jewish community of Spain. By profession, he was a physician. Yitzhak Baer describes Shabbetai as a poet who moved in aristocratic circles in Toledo and later in Saragossa. He notes that there was a type of Jew who was reluctant to submit to the organized authority of their community. These individuals belonged to a well-educated class which cultivated Arabic culture. Political, social, and economic differences presented a wide gulf separating them from the Jewish masses. According to Baer this is reflected in Divrei ha-Alah ve-ha-Niddui.3

Stylistically, Shabbetai was a master of the “mosaic” style who skillfully applies Biblical and Talmudic phrases, his humor being spontaneous according to Richard Gottheil and H. Brody.4 In his works, Shabbetai follows the Andalusian Arabic pattern of a long narrative with different episodes.

Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim was first written by Shabbetai in 1208 when he was twenty years old; it was revised twenty years later (1228) at forty. A small work, Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim was first printed in Constantinople at the press of Eliezer ben Gershom Soncino in c. 1543 in octavo format (80: [24] ff). Concerning that press, Eliezer came to Salonika from Rimini with his father, the renowned pioneer of Hebrew printing, Gershom Soncino, in 1526. After printing several works, Eliezer left Salonika in 1529 for Constantinople. He returned to Salonika, however, where he printed the title Me’ah She’arim in 1543, before returning to Constantinople where he resumed printing Hebrew books. Eliezer printed until 1547, a year before his death, when he sold the printshop to Moses ben Eliezer Parnas, a former employee and partner. A less known aside of interest is that in Cairo, Gershom ben Eliezer Soncino, grandson of Gershom Soncino, printed at least two books, Pitron Halomot and Refu’ot ha-Talmud (1557), both unicums unknown until recovered from the Cairo Geniza.5

Raymond P. Scheindlin compares Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim to Euripides’ Hippolytus in the introduction to his 1990 translation; he describes it as the main Hebrew contribution to the theme of love’s revenge. Scheindlin also notes that the narrative at the beginning, after the death of Tahkemoni, is comparable to the death of the king of Navarre in Shakespeare’s Love’s Labor’s Lost. He concludes that Minhat Yehudah is an early example, indeed “the first extensive one, of Hebrew parody.”6

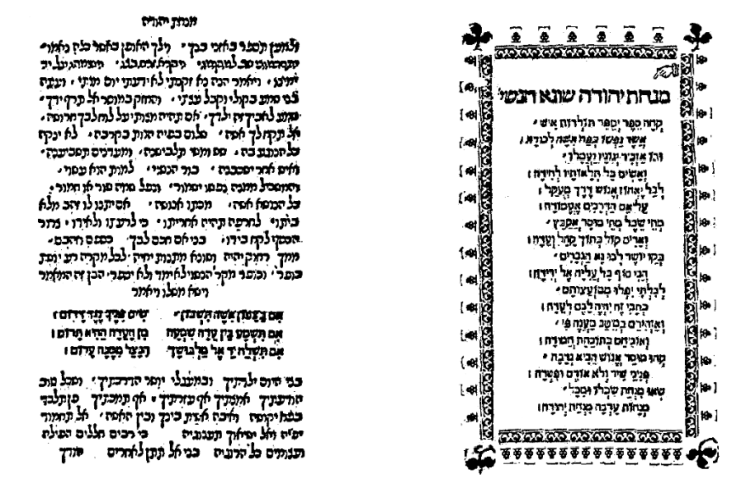

Shabbetai wrote Minhat Yehudah to gratify friends who had requested that he recount poetically how he came to be a married man. Shabbetai dedicated it to his patron and protector, Abraham Alfachar (Alfakhar) ben ha-Yozer, an important Jewish official at the court of the Castilian king, Alfonso VII. The title page of Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim, enclosed in a frame with an outer border of florets and text set in square vocalized letters begins;

Take this book, which recounts the story of a man,

whose soul was caught in the snares of a woman.

In it I will relate his sorrows and his struggles,

and I will make his tribulations a by-word,

so that men shall not take to the side paths

but keep to the middle road of life.

I will gather men of moral character,

and lift up my voice in the assembly and say:

‘Men, go in a straight line,

for all climbing ends in going downward.’

So as not to fall into their counsels

I have written this as a testimony.

And I caution them with the best of my sayings.

And I will reprove them with sweet reproofs.

Take one’s ethical teachings and bring free will offering,

pearls of song and not rubies and topaz.

Bear the offering of heart and heart totally.

A pleasant offering the offering of Judah.7

The title page is followed by Shabbetai’s introduction which begins by informing how the sea of marriage affects a man and how a thousand in Judah are washed and passed over. In Israel Zinberg’s opinion, the introduction has no relation to the substance of the romance. He relates, in satirical fashion, “how in a certain country grew up a ‘foolish, ignorant generation’ which declared war on all the sciences and persecuted its wise men and scholars.” Somewhat similarly, Israel Davidson writes that the appositional title, Sone ha-Nashim created the impression that it was a misogynist work. Internal evidence suggests that the satire is directed against the woman hater as much as against women, is a parody opposing extremes, and cautions against hasty marriage.8 This is supported by the opening paragraph of the introduction, which states:

Take this book which tells the story of a man whose soul was caught in the snares of a woman. I will tell in it his sorrows and his struggles and I will make his tribulations a by word so that men shall not take to the side paths but keep to the middle of the road of life. I will gather men of understanding and men of moral character and lift up my voice in the assembly and say go you men in a straight line for all climbing ends in going downward.9

c.1543, Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim,

Constantinople

Courtesy of the Jewish Theological Seminary

The text, which is not paginated, follows. It is comprised of leading lyrical lines in square vocalized letters followed by the commentary in rabbinic letters. It is written as a maqama (maḳamah), a narrative in rhymed prose, mixed with metrical poems.

In the text a narrator, a heavenly spirit, appears to Judah and adjures him to compose an admonitory work to prevent his friends from being entrapped in the dangers of marriage. In the tale, the protagonist, Zerah, promises his father, Tahkemoni, a wise man who was disappointed in marriage, before the latter’s death that he will never marry. In Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim, Tahkemoni beseeches Zerah to avoid women throughout his life:

Cursed is he who brings a woman into his house. Every trouble has a remedy. Every misfortune a limit, but a married man is lost forever. No one can help him anymore. . . . Remember then, my son, if you see a woman northward, quickly turn your face to the south. If you hear her voice in some gathering, leave the crowd as quickly as possible. If a woman takes hold of your garment run away naked from her.10

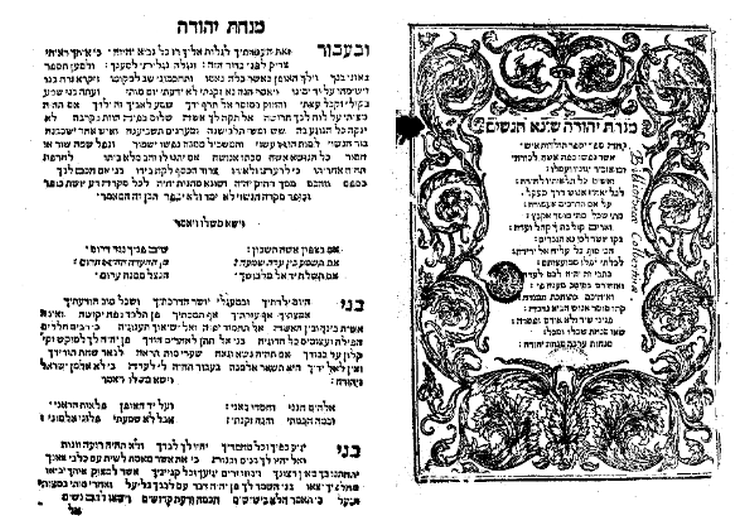

1602, Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim, Salonika

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Zerah promises to obey his father and crusades against marriage with three friends who concur so, alarming women that they plan his downfall. One of them, Cozbi (Falsehood), with the aid of her husband, Sheker (Lies), finds a beautiful woman, Ayala Sheluhah (Doe Let Loose [Genesis 49:31]), whom they induce to flatter and cause Zerah to fall in love with her. The plot is successful and Zerah, smitten, proposes marriage and a ketubbah (marriage certificate) is written. Just before the wedding, however, the beautiful woman disappears to be replaced at the ceremony by Ritzpa bat Ayah (II Samuel, 3:7, 21:8), a hideous, ill-tempered, and garrulous hag whom Zerah marries. When he discovers his mistake in the morning, too late to rectify the situation, the hag reviles him and then sends him for food and drink. Zerah’s friends console him, much as did Job’s companions, recommending divorce. However, the women bring the matter before the king, testifying to Zerah’s past behavior and the consequences if he is permitted to divorce. At the end it is made clear that the marriage is a fiction. Another example of the text is:

Now Zerah was more skilled at poetry and its conceits than any man before him. So he answered her with a speech commensurate with his skill, and took up his rhyme:

Your hair is like the dark of night,

Your face as morning fair;

Let not your brilliance startle you

Or your raven-colored hair.

When the girl saw how she had pleased him and that she could win him with fine verses, she took up her rhyme:

Fear not fawn’s eyes although they threaten

Death to every man alive;

Their eyes may sting, but when the victims

See them they at once revive.11

The next edition of Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim was printed in Salonika in1602 at the press of Abraham ben Mattathias Bath-Sheba, under the sponsorship of R. Moses de Medina. That press is credited with about forty titles from 1592 to 1605.12 It was followed by editions in Frankfurt on Main (1856) and a possible undated Venice edition.13 The National Library of Israel catalogue also records a 1956 Jerusalem edition.14 Minhat Yehudah is one of the works included in the famed Rothschild Miscellany (382r-393r).

Several dates have been suggested for when Shabbetai wrote Minhat Yehudah. The earlier date, 1208, seems most likely as a satire in rebuttal of Minhat Yehudah by a poet named Isaac, entitled Ezrat Nashim (The Help of Women), is dated 1210. Zinberg writes that the author found it necessary to champion the honor of women, declaring that “this work will rejoice all persons in love who walk arm in arm in the fragrant fields under the shade of myrtle and lemon trees.” He concludes, however, that the literary value of Ezrat Nashim is “very meager” and the story “childishly naïve.”

According to Jill Jacobs, Ezrat Nashim sees Minhat Yehudah as a serious misogynist work and is intended to defend women from its’ charges against them. In style, Ezrat Nashim is modeled after Minhat Yehudah; in it, Absalom, a father instructs his son, Hovav, to find and marry the perfect woman. He finds the ideal women, Rachel, who is beautiful and chaste. The story continues as a refutation of Minhat Yehudah and includes a series of biblical verses celebrating love and marriage.15

A second rejoinder to Minhat Yehudah is Ein Mishpat, also apparently written by Shabbetai in 1210, according to Tova Rosen.16 Yet a third rejoinder is Ohev Nashim (The Lover of Women), written in 1298 by Jedaiah ha-Penini (Bedersi, c.1270-c.1340) when he was eighteen. Ohev Nashim is also comprised of rhymed prose, epigrams, and parables. He is best known for his ethical works, Beḥinat ha-Olam (Mantua, 1474) and Sefer ha-Pardes (Constantinople, c. 1515).

Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim has proven to be a popular work. Rosen informs that there are as many as twenty-seven extant manuscripts, apart from several editions generally printed together with other works. Perchance, evidence for the popularity of Minhat Yehudah from a very early period can be found in a postscript to Shabbetai’s 1228 edition. Zinberg informs that Shabbetai complained that Minhat Yehudah had been plagiarized; several poems from that work had been “passed off” by someone as his own. In an aberrant and perverse way, that might certainly be considered a form of praise and evidence of a work’s popularity.17

Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher, Judah ben Isaac ibn Shabbetai’s second work, is a humorous dialogue over the merits of wisdom and wealth. It was written in 1214, according to Israel Davidson who sees it, moreover, as a didactic work intended not only to instruct but also to be amusing and pleasing to the reader. Meyer Waxman suggests that, despite its humor and its “bristling with puns and parodies” Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher is not to be considered a satire, as it describes the right way of life and conduct.18

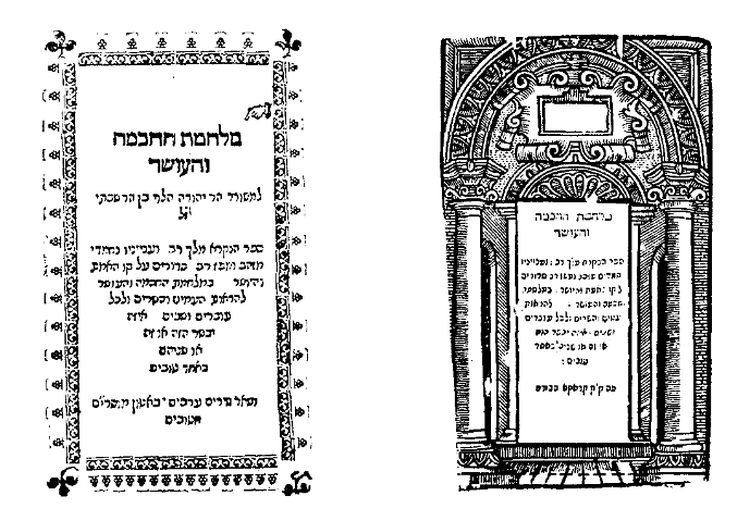

It, too, was first printed in Constantinople at the press of Eliezer ben Gershom Soncino in c. 1543, according to Yaari.19 A small work, Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher was published in octavo format (80: 16 pp.). The National Library of Israel catalogue, however, gives the publisher as unknown, which appears questionable as they attribute Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim to the press of Eliezer Soncino, both works having been published at approximately the same time and, significantly, when there was only one publisher in Constantinople at the time.20

Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher was subsequently published in Cracow in c. 1546, also in octavo format (80: 6 ff.). Although rare, the Constantinople printing is more common than the Cracow edition, which is recorded by Steinschneider and Cowley in their catalogues of the Bodleian Library.21 Although undated, both Steinschneider and Cowley date it to 1543. That date seems improbable, as the previous Cracow printers, the Halicz brothers, had ceased printing books of interest to the Jewish community by 1540, and the next Cracow press, that of Isaac Prostitz, did not open until 1569. Vinograd dates it as a 1546 imprint, while Friedeberg does not date this edition in his Bet Eked Sepharim.22 The National Library of Israel dates this edition of Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher to c. 1590. Given this work’s small size, when reprinted, it is included in collections of several small works.

The Constantinople edition of Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher reputedly has verse at the end not present in the Cracow edition. The title page of the latter edition is identical to the previous edition except for the omission of the final line “and other Arabic songs in a good moral song sung well.”

According to Schirmann and Sáenz-Badillos, Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher “apparently was dedicated to Todros b. Judah, the father of Meir Abulafia, who acted as judge in the quarrel in question between two brothers, one of them rich and the other wise, disputing about a tiara left to them by their father.”23 The title page states that:

This book is entitled the ‘great king’ (Psalms 48:3, Daniel 2:10) and its subject matter, ‘“is more to be desired than gold, even fine gold’ (Psalms 19:11), arranged in a manner (line) that is true and right, the war of Wisdom and Wealth. ‘To show the people and princes’ (Esther 1:11), and to all passersby, ‘which shall prosper, this or that, or whether they both alike shall be good’ (Ecclesiastes 11:6). And other Arabic songs in a good moral song sung well.

c. 1543, Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher 1546, Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel Courtesy of Hebrew Books.org

Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher was also written as a maqama, a narrative in rhymed prose, mixed with metrical poems. As noted above, it is a humorous and also didactic work, with numerous puns, attempting to direct man to the correct way of life and conduct. The text is a dialogue between twin brothers, Peleg and Yaktan, over the merits of wisdom and wealth.

The brothers represent, respectively, the pursuit of wealth and wisdom. Their father, as a last bequest, divides his wealth equally between his sons, except for a precious crown with magical powers of assuaging pain, whose possession is not designated. Peleg and Yaktan dispute over the crown, the former contending that its greatest importance is wealth, more than wisdom or even religion, while the latter argues that it is wisdom that prevails. He, therefore, should have the crown. In their arguments both brothers quote, often in a humorous fashion, from biblical and Talmudic sources and from Jewish history in support of their position. They bring their case to trial before R. Todros ben Judah Abulafia of Toledo. Peleg presents supporting documents from the biblical figures Jeroboam ben Nebat and Elisha ben Avuyah. Yaktan cites Joseph and Solomon. The court decision is that both wisdom and wealth are pillars of society, necessary for a happy life and one must not be followed to the exclusion of the other, expressed as a pesak din (legal decision).

According to Waxman, the moral of this discourse is that in life one must pursue both wisdom and wealth, not following one to the exclusion of the other. The instructions from the dialogue are neither deep nor lofty, the primary interest in this work not its content but its form. He concludes “to one who is conversant with Hebrew, the brilliant puns, the clever twists of parody, and the witty arguments of the contestants afford great delight and pleasure.”24 In contrast, Davidson is also critical, stating that there is no special merit in parody, but nevertheless Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher deserves mention as the first of its kind. Moreover, it gains interest when compared with similar satires in the literature of the middle ages. Zinberg is most critical of Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher. He is very negative on it, writing that it is a didactic poem whose “poetic value is very slight. The subject and content are clumsy and crude. There is also little originality in the moral of the work, namely that wisdom and wealth ought to live together amicably because they cannot get along without one another.”25

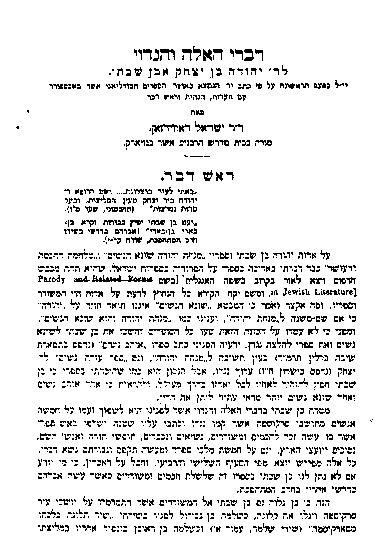

Divrei ha-Alah ve-ha-Niddui, is our final Judah ha-Levi ben Isaac ibn Shabbetai title. It is a satire. Printed several centuries after Shabbetai’s earlier works, it was, rightly, as we shall see a controversial work.

As noted above, Yitzhak Baer informs that Shabbetai moved in aristocratic circles, as reflected in Divrei ha-Alah ve-ha-Niddui. It is a work that eulogizes scholars, poets, and notables, who aided their people in times of stress. Also included is an account of the “exploits of ‘the five kings of Spain.’” According to Baer, Shabbetai appears to have been the first Jew who interested himself in the chronicles of Spanish rulers and was impressed by their accomplishments.26

1909, Divrei ha-Alah ve-ha-Niddui

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

The pious Jews of Saragossa declared Divrei ha-Alah ve-ha-Niddui a heretical work because of the positions and attitudes taken by the author Shabbetai was excommunicated and the book burned in the synagogue’s courtyard. Shabbetai responded with satire towards the “vicious foxes and scorpions . . . stupid and heartless folk,” accusing them of intimacy with their slave girls and denouncing them for tax evasion and similar crimes. According to Davidson, he inveighed and used all the “piquant epithets at his command” unsparingly. He begins the satire listing his grievances against the five prominent men of Saragossa, but is most harsh on Abraham ben Samuel Lobel, the community secretary. Shabbetai charges Lobel with forgery, bribery, and extortion, writing that if Lobel attends a wedding:

the marriage is sure to turn out a failure. If he prays for the sick, they are sure to die, if he prays for rain in a dry season, there is sure to be a drought in the land, and woe to the departed soul at whose funeral this mans should deliver the oration, for then God will surely be severe in his judgment.

He is more lenient with the other four men, but they, too, are included in a ban, assigned to everlasting perdition.

Baer concludes his description of that work with “there is no way of telling whether there was any basis to these charges. Undoubtedly, the traditionalist, whom the poet calls ‘men of folly,’ made up the great majority of the Jewish population.”27 Perchance, this is why it took almost a millennium to publish Divrei ha-Alah ve-ha-Niddui, which first appeared in 1909, when Israel Davidson published it in Ha-Eshkol.

According to both Davidson and Jefim (Hayyim) Schirmann / Angel Sáenz-Badillos, Shabbetai also authored a work on the history of the great men of his day, but the leaders of the community of Saragossa destroyed or burned it; it is no longer extant.28

Two of Shabbetai’s works, Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim and Milhemet ha-Hokhmah ve-ha-Osher were well known, They are recorded in various bibliographies, for example, Shabbetai ben Joseph Bass’s (1641-1718) Siftei Yeshenim (Amsterdam, 1680), the first bibliography of Hebrew books by a Jewish author.29 They are also recorded, in greater detail, in Moritz Steinschneider’s Catalogus Liborium Hebraeorum in Bibliotheca Bodleiana (Berlin, 1852-60).

The above works, particularly Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim, do not seem sufficiently objectionable, to have aroused the intense opposition and objections they received. David Stern, writing about early medieval Jewish literature in general, offers a description of contemporary writing that seems appropriate to this subject. He notes that imaginative fiction “was most likely to be looked upon with ambivalence if not contempt, and not infrequently by the very authors of works that we should consider to be among the greatest products of the imagination.” He further comments that in the history of Jewish literature prior to the nineteenth century, there was a negative attitude towards imaginative writing, more often the rule than the exception.30

In retrospect, the works of R. Judah ha-Levi ben Isaac ibn Shabbetai appear to fall into the category of imaginative fiction, the more objectionable due to their considerable popularity. With that in mind, we can appreciate that Shabbetai was an author of works of interest that varied from contemporary standard Jewish literature. They aroused opposition, serious opposition as we have noted which did not detract from their popularity. Unfortunately, however, his later works suffered because of the opposition. Nevertheless, Shabbetai’s books remained available and, in some circles, popular; today we can recognize them as works of quality.

1 The two images surrounding the title of the article are on top: Halloween Witch Broom Cat by Martina Stokow; and below: Lilium Auratum by John Frederick Lewis.

2 Marvin J. Heller is an award winning author of books and articles on early Hebrew printing and bibliography. Among his books are the Printing the Talmud series, The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book(s): An Abridged Thesaurus, and several collections of articles.

3 Yitzhak Baer, A History of the Jews in Christian Spain, translated from the Hebrew by Louis Schoffman, vol. I (Philadelphia, 1966), p. 94.

4 Richard Gottheil, H. Brody, “Judah ibn Shabbethai (known also as Judah Levi ben Isaac),” Jewish Encyclopedia, vol. 7 (New York, 1901-06), p. 358; Jefim (Hayyim) Schirmann / Angel Sáenz-Badillos, “Judah ben Isaac ibn Shabbetai,” Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. 11 (Jerusalem, 2007), pp. 487-88.

5 A. M. Habermann, Ha-Madpesim B’nei Soncino (Vienna, 1933, reprinted in Studies in the History of Hebrew Printers, Jerusalem, 1978), pp. 93-94 nos. 1, 2 [Hebrew].

6 Raymond P. Scheindlin, “The Misogynist by Judah Ibn Shabbetai” in Rabbinic Fantasies: Imaginative Narratives from Classical Hebrew Literature, David Stern and Mark Jay Mirsky, eds. (Philadelphia, New York, 1990), pp. 269-83.

7 Avraham Yaari, Hebrew Printing at Constantinople (Jerusalem, 1967), pp. 99 n. 134 [Hebrew].

8 The following description of Minhat Yehudah Sone ha-Nashim is based on Israel Davidson, Parody in Jewish Literature (New York, 1907, reprint New York, 1966), p. 11; Meyer Waxman, A History of Jewish Literature (1933, reprint Cranbury, 1960), II, pp. 604-05; and Israel Zinberg, A History of Jewish Literature I (New York, 1975), translated by Bernard Martin, p. 178.

9 Zinberg, op. cit.

10 Zinberg, op. cit.

11 Scheindlin, op. cit.

12 Concerning the Abraham ben Mattathias Bath-Sheba press and an unusual edition of tractate Berakhot published by the press see Marvin J. Heller, “The Bath-Sheba/Moses de Medina Salonika Edition of Berakhot: An Unknown Attempt to Circumvent the Inquisition’s Ban on the Printing of the Talmud in Sixteenth Century Italy,” Jewish Quarterly Review, LXXXVII (Philadelphia, 1996), pp. 47-60, reprinted in Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book. (Leiden/Boston, 2008), pp. 284-97.

13 Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. Listing of Books Printed in Hebrew Letters Since the Beginning of Printing circa 1469 through 1863, I (Jerusalem, 1993-95), p. 316 [Hebrew]. The Frankfurt edition is one of several works included in Ta’am Zekanim, a collection by Yedei Eliezer Ashkenazi. Gottheil, H. Brody states that it was also was also printed as an appendix to Abraham ben Ḥasdai's Ben ha-Melek we ha-Nazir (Warsaw, 1894).

14 Minhat Yehudah was sold at auction by Kestenbaum & Company on September 20th, 2005, Auction 30, lot 286. The estimated price was $4,000 - $6,000, price realized $2,800. It is noted in the catalogue description of Minhat Yehudah that “The date of the mock Kethubah in this tract, “4777” [1017] is an obvious printer’s error. It should read “4977” [1217], when it is believed ibn Shabtai composed the work.”

15 Jill Jacobs. “The Defense Has Become the Prosecution:” Ezrat HaNashim, a Thirteenth-century Response to Misogyny . Women in Judaism: A Multidisciplinary E-Journal, (2005), 3(2). Also see Talya Fishman, “A Medieval Parody of Misogyny: Judah ibn Shabbetai’s Minhat Yehudah sone hanashim” in Prooftexts, (January, 1988), 8:1, pp. 67-87.

16 Tova Rosen, “Sexual Politics in a Medieval Hebrew Marriage Debate,” in Jewish Medieval Studies and Literary Studes (2004, reprint 2007), pp. 145-71.

17 In contrast, Davidson notes that in the epilogue of a later edition of Minhat Yehudah Shabbetai refutes accusations of plagiarism brought against him by Hayyim ibn Samhun.

18 Davidson, Parody op. cit.; Waxman, pp. 585-86

19 Yaari, Hebrew Printing at Constantinople, Jerusalem, 1967, p.99. no.133 [Hebrew].

21 A. E. Cowley, A Concise Catalogue of the Hebrew Printed Books in the Bodleian Library (1929, reprint Oxford, 1979), p. 369; Ch. B. Friedberg, Bet Eked Sepharim, (Israel, n. d), mem 2002 [Hebrew]; Moritz Steinschneider, Catalogus Liborium Hebraeorum in Bibliotheca Bodleiana (Berlin, 1852-60), col. 1370 n. 5769; Vinograd, II, p. 633 no. 20.

22 See note 21.

23 Encyclopedia Judaica, op. cit.

24 Waxman, op. cit. p. 586.

25 Zinberg, op. cit.

26 Baer, op. cit.

27 Baer, op. cit.

28 Davidson, op. cit.; Jefim (Hayyim) Schirmann / Angel Sáenz-Badillos, EJ, Previous citation.

29 Shabbetai Bass, Siftei Yeshenim (Amsterdam, 1680), pp. 43, 44 nos. 178, 216 [Hebrew]. Moritz Steinschneider, Catalogus Liborium Hebraeorum in Bibliotheca Bodleiana (Berlin, 1852-60), col. 1370 n. 5769.Concerning Shabbetai Bass, see Marvin J. Heller, “Bass, Shabbetai ben Joseph Meshorer,” The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, Gershon David Hundert, ed. (New Haven & London, 2008), pp. 129-30.

30 Stern, op. cit., pp. 4, 5.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800