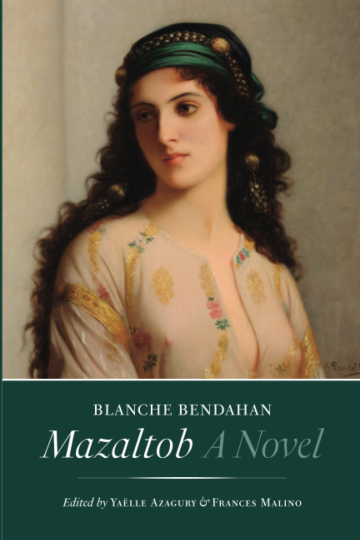

Blanche Bendahan

Translated and edited by Yaëlle

Azagury and Francis Malino

MAZALTOB: A NOVEL

Waltham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press, 2024, ISBN: 978-168458-2051

Reviewed by Judith Roumani1

This important translation brings to the fore a novel which has been overlooked within the genre of North African Jewish Francophone novels. I think I should also plead guilty, among the scholars in this field, of not giving Blanche Bendahan’s work the weight it deserves, among the plethora of mostly male novelists of several generations. This novel was first published in 1930, and to my knowledge only one Jewish woman novelist preceded Bendahan, that is Elissa Rhaïs, who published very popular novels from about 1920 on. After Elissa Rhaïs, we have not seen French language Jewish women novelists publishing until the 1970s or so. A much more modern generation has been led by Nine Moati of Tunisia, followed by Gisele Halimi, Annie Cohen, Annie Fitoussi, Chochana Boukhobza, and others.2 An exception, perhaps, though not really a bridging one, might be the fiction and critical writings of Jacqueline Kahanoff in the 1950s and 1960s. Though she spoke French, Kahanoff wrote in English and was translated and published in Hebrew. It would be something of a stretch, perhaps, to claim Bendahan as the founder of this genre of feminist writing, as she did not have any immediate successors who could claim to have been influenced by her. The translator-editors do claim her, not as the initiator, but as a forerunner and model.

The novel is set almost entirely in in the Jewish quarter or judería of Tetouan, the Spanish enclave surrounded by Morocco, where the beautiful and intelligent Mazaltob has grown up in the very traditional, somewhat closed and hidebound Jewish society in the early twentieth century. She manages to secure some education, and even has singing lessons from the wife of a diplomat. The good fortune implied in her name is cut short by her arranged marriage to a boor of a man, a Tetouanese who arrives from the Argentine seeking a wife, then promptly abandons her. As a married woman in Tetouan, she has been forced to abandon her voice lessons, and though she never has her own child, acquires family responsibilities, raising her younger sibling after her mother passes away in childbirth. Though domestic labor and responsibilities consume her time, her active and inquiring mind and thirst for knowledge lead to a close relationship with certain outsiders, such as the local Ashkenazi doctor and his half-Jewish son Jean.

These two characters open Mazaltob to an outside world of vast cultural horizons. Though unfulfilled and hemmed in by her local environment, Mazatob remains loyal to her birth culture and her religion. Eventually, and inevitably, the half-Jewish Jean and she fall in love with each other. A plan is hatched for them to elope together; they start off on their journey. But Jean anticipates their relationship by planting a passionate kiss too soon, causing Mazaltob to take fright or take refuge in her tradition and abandon him, fleeing back to Tetouan. Jean pines away and dies, followed at the very end of the novel by Mazaltob, and she is buried near him in the cemetery of Tetouan. Though not technically Jewish, and indeed something of an atheist, Jean gains access to the Jewish cemetery where he knows his beloved will lie by bequeathing his entire fortune to the poor (p. 126). His epitaph will have neither Hebrew nor Latin words, merely “Herein lies Jean/Who loved and died” in French. Mazaltob meditates on some stanzas from a poem that Jean had left:

“Like a conspiracy, despite the shimmering lights from the West, dusk weaves its nightly web…..The same had been true for her, for Mazaltob….Despite the intellectual light coming from the North, her blood spun the dark conspiracy of instinct within her ” (127).

Yaëlle Azagury, in her postscript essay, “Mazaltob and the Modern Sephardic Novel,” insightfully places this work within the progression of the novel and its task of leading Sephardim toward modernity. Like many important experiments, Mazaltob details a failure. Later traumatic events, the war, the Holocaust, the expulsion of Sephardim from their ancestral homes, will irrevocably uproot her people and hurl them into modernity, willy-nilly. Mazaltob precedes these and still has a choice, and she chooses in the end to honor and uphold her tradition, though the price is devastating, leading to the deaths of Jean and herself. A generation later, there will be no such choice for the Jews of North Africa and of the Middle East. The outpouring of novels that followed, after a pause, contrasts with that of Bendahan, with a rawness and implacability imposed from without by history, rather than arising within the mind and choices of a single heroine. But her dilemmas did still haunt the minds of the next generation, many of whom most reluctantly gave up tradition, and did everything they could to recreate it on a different basis, in their new homes. But they are now a different breed, a century later facing issues that Mazaltob never dreamed of and always buffeted by history which continuously tries to impose change. This novel, Mazaltob, is a wonderful point from which to observe the future, which is now the past for us. We can empathize with Mazaltob, just as we measure the distance and the gulf that lies between us.

Azagury and Malino have done us a tremendous service by making this seminal novel by Bendahan accessible in English translation, thereby helping us to build a canon of Sephardic novelistic creativity by women writers in French.

1 Judith Roumani is the editor of Sephardic Horizons.

2 Readers will want to consult the review in Sephardic Horizons 7: 3-4 (Summer-Fall 2017), by Youness Abeddour, of the book by Nina Lichtenstein, Sephardic Women Writers: Out of North Africa, Santa Fe, NM: Gaon Books, 2017.