Another Bureaucratic Dance for the Sephardim: The Iberian Naturalization Laws of 2015

By Lauren Weiner1

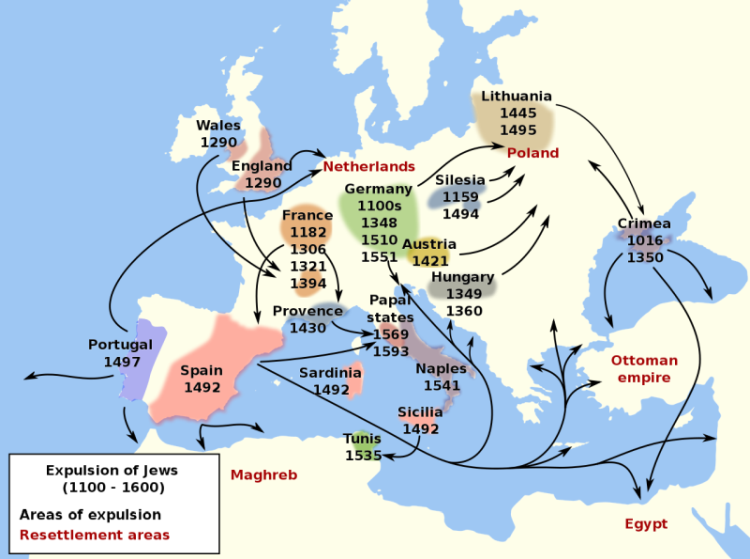

The history of the Iberian Peninsular Jews—the Jews of Sefarad—is one of high accomplishment followed by repression, secret defiance, and flight into the Diaspora. At the end of the 15th century, Spain’s and Portugal’s monarchs imprisoned, expelled, killed, or forced Christianity on the largest Jewish community anywhere in the world. According to historian Jane S. Gerber, before leaving Spain in 1492 by order of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabel, the Sephardim were charged prorated taxes to cushion the loss to the Spanish treasury that their absence portended. The refugees exited in many directions, with around 120,000 Castilian Jews, according to Gerber, leaving for Portugal. There, João II granted the Spanish Jews an eight-month stay in Portugal in exchange for “a hefty fee,” and those who could not afford to pay the fee “were forthwith sold into slavery.”

Upon João’s death, Manuel I took the throne and ordered the liberation of those enslaved by his predecessor. Portugal lacked a mercantile class, and Manuel wanted to foster one in the Sephardim. The plan was interrupted by his bid to marry Ferdinand and Isabel’s daughter. His future in-laws demanded that he adhere to the Inquisition (which had not yet spread to Portugal) by banning Judaism and expelling the former Spanish subjects who had come to his country. Manuel duly ordered that they be cast out.

Manuel’s 1496 edict was reluctantly issued. “Unlike Spain,” wrote Gerber, “his kingdom did not have a converso population that could remain behind to serve as the nation’s middle class after the expulsion. He wanted, therefore, to eliminate Judaism while retaining the Jews. His solution was to try to force all Portuguese Jews to convert.” The number of expulsions from Portugal under Manuel’s reign was not high, according to historians. Most of the Sephardim stayed and became “New Christians.” With their varying degrees of sincerity in adopting their royally-assigned faith, and with many clandestinely keeping to Judaism, the “New Christians” were ever after regarded with suspicion by the “Old Christian” population of Portugal. When the Inquisition officially arrived, in 1536, waves of dispossessions and autos da fé took place in Portugal for the next 230 years.

.png)

“The Banishment of the Jews” by Alfredo Roque Gameiro, 1917, from

Quadros da História de Portugal.

As those who escaped the Inquisition with their lives (not their property) moved about the globe, they were fortunate in one respect: The religious wars of the Reformation and Counterreformation were yielding to a new appreciation, in England and parts of the Continent, of the advantages of tolerating the Jews. The Sephardim thrived commercially, some of them as Jews and some of them as Catholics. Which was which became opaque. In Gerber’s words: “These Portuguese-speaking merchants were distinguished by aristocratic bearing, a sense of pride, and a need to remain inconspicuous, born of the hazardous experience of having been crypto-Jews under the gaze of the Inquisition.”2

Today there is no secrecy, no need for protective ambiguity. Quite the opposite, if you can “prove your lines”—that is, establish your descent from Sephardic Jewry—a benefit may accrue. That benefit is Portuguese or Spanish nationality, under laws passed a decade ago. Spain’s 2015 law sunsetted but Portugal’s, adopted earlier in that same year, remains on the books in amended form.

To seek atonement for a historic wrong is laudable. Prominent Jews argued for these laws, to be sure. The Christian impulse of, in particular, former legislator José Ribeiro e Castro (the Portuguese law’s main sponsor) was good. The idea has been discussed for over a century. Yet the beau geste of the Iberians has not been beau in the execution. The nationality concessions have been marred by legal and bureaucratic snarls, political controversy, and, in the case of thousands of aspirants to Portuguese and Spanish citizenship, disappointed hopes. Not to mention the spectacle of the police arresting a rabbi in Porto for certifying the Sephardic ancestry of a Russian oligarch (more on that later).

Neither government adequately prepared itself to handle the deluge of nationality requests that began pouring in from around the globe even before the laws took effect. Understaffed government bureaus were beset; that was one problem, to which was added the headache of verification. It was natural enough that Portugal and Spain should require proof of Sephardic lineage to qualify for citizenship under their respective laws. Because who counts as a Sephardic Jew is, to put it mildly, an inexact science, it was also asking for trouble. Obscuring the picture are the facts that many Ashkenazi liturgical practices and traditions, such as praying at the Western Wall, come originally from the Sephardim, and that, beginning in the early 19th century, the two groups began to intermarry.

The two governments enlisted religious authorities and Sephardic federations to vouch for applicants’ connection back to Jews expelled from Spain or forcibly converted in Portugal. But in both cases not enough forethought was put into standards for the outside groups to follow, making the supervision of verification erratic. The result: The administration of the 2015 nationality laws proved unwieldy, arbitrary, and vulnerable to allegations of grants of citizenship to people who faked their Sephardic credentials.

Sefarditismo Económico

Anyone going into a state of high dudgeon over the infection of these programs by fraud needs, first, to reckon with the frequency with which the Iberians solicit new citizens and residents. Several such efforts have come down the pike. The 2007-2009 financial crisis was a spur to nationality-concession. Spain and Portugal offer “golden visas,” as do many other countries, to those willing to invest in local businesses or purchase local real estate. Portugal has had such a program since 2012, Spain since 2013. Anti-corruption activists have called on the European Commission to get after its member states (not just the Iberians, but including them) for their easy and non-safeguarded pathways to residency and citizenship.

The granting of citizenship is a partisan political matter in both democracies. The Spanish government, under the Socialist premiership of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, passed a Law of Historical Memory in 2007 to offer “Spanish nationality by option, for the benefit of descendants of Spanish nationals who were exiled during the Spanish Civil War and the dictatorship.” In 2022 came the Law of Democratic Memory, which widened the eligibility, being intended for “those born outside Spain to a father or mother, grandfather or grandmother who were originally Spanish and who, as a result of being forced into exile due to political or ideological reasons, reasons of religious belief, or sexual orientation and identity, lost or renounced their Spanish nationality”—or who filled still other categories. The political left, in other words, used nationality laws to cater to the groups within its coalition. So did the political right. When the right-of-center parties (the Christian Democrats and Social Democrats in Portugal, the People’s Party in Spain) got elected early in this century, and again between the 2007 and 2022 laws just mentioned, they rekindled efforts to naturalize Sephardic Jews.

Theoretically, all of the motives—economic, political, moral, humanitarian—to reach out to presumably prosperous members of Sephardic Jewry might not sit well together; practically speaking, however, no problem. The Iberian nations, with their castles and cafes and coastal splendors, want to attract tourism and taxpaying retirees like other countries do. More than other countries do, if one considers the teetery condition of their public finances going back quite some time. (See above description of the monarchs.) The history of sefarditismo económico is long and tortuous. It has involved “dubious passports, desperate backup plans, and extraterritorial dreams that [have] been central to Sephardi life for centuries,” in the words of Sarah Abrevaya Stein, a historian of the Ladino-speaking eastern Sephardim who established themselves in the lands of the Ottoman Empire.

“From the Spanish and Portuguese perspective,” Stein wrote, “Sephardi Jewish protégés were a vehicle of colonial ambition.” The historians Dalia Kandiyoti and Rina Benmayor, too, speak of Iberian “colonial conquest and ambitions,” adding that “the ‘discovery of’ and ‘reconnection with’ Moroccan Sephardi Jews in the context of Spain’s early twentieth-century colonization of part of the North African country played a particularly important role, though Sephardi Jews elsewhere, especially in the Ottoman Empire, too were of interest.” They cite the Spanish senator, writer, and philologist Ángel Pulido Fernández as preeminent among a group of diplomats and intellectuals bent on recruiting the descendants of the expelled Jews “to serve as so-called agents of Spain from the Balkans to North Africa.” Pulido Fernández, according to Stein, campaigned to “rehispanicize” those whom Spain “had long ago ‘hemorrhaged,’ in order to help restore the commercial and cultural might it had lost” when it met with defeat in the Spanish-American War of 1898.3

Acting along the same lines, around the same time, was a new republican government in Portugal. (The two countries’ movements in tandem form a persistent pattern, if not one that either country is apt to acknowledge.) The Portuguese government set its cap for the Jews of Salonica, the majority-Sephardic port city that Greece conquered in 1912-1913 from an Ottoman Empire on the wane. The rule of the Ottoman Turks, who had allowed the Jews to flourish, was being upended. Stein, in her 2016 essay for the Jewish Review of Books, described wartime chaos in which “the Portuguese consul in Salonica, Salomão Arditti (himself a Jew), registered 500 Jewish families as Portuguese subjects,” which led to “decades of confusion for paper holders and Portuguese state representatives alike. . . . Some Jewish families [who] registered in 1913, unsure of the legal value of the papers they held—or, possibly, intent on maximizing their worth—found themselves commencing a decades-long bureaucratic dance with Portuguese officials.”

A decree promulgated in 1924 by the Spanish dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera, with King Alfonso XIII’s acquiescence, recognized extraterritorial Spanish subjects living in the former Ottoman areas. The 1924 decree was a legal landmark (the 2015 law’s sponsors often hearkened back to it) but, with its generalized wording (it failed to explicitly mention the Sephardim), it benefitted but a few thousand of the approximately 70,000 Salonican Jews.4 During World War II, the Spanish government rescued Jews fleeing Adolf Hitler’s Germany in fits and starts, efforts that picked up speed as Francisco Franco’s ally began to lose the war and Franco reoriented Spanish policies toward the Allied countries. After Franco—who in 1968 revoked Isabel and Ferdinand’s expulsion order—King Juan Carlos I harbored, and his son King Felipe VI continued, philosemitic intentions.

For a century, from the World War I period until the second decade of the new millennium, when Ribeiro e Castro in Portugal and Justice Minister Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón in Spain floated the idea of new nationality laws, a steady stream of Sephardic Jews around the world had been seeking, and in some cases receiving, recognition of their Iberian connection. Spain considered their citizenship applications on a case-by-case basis. It was slow work and, after a legal tweak in 2006, involved either 1) fulfilling a two-year residency requirement or 2) procuring a carta de naturaleza or discretionary grant of citizenship under “exceptional circumstances from the King of Spain.”5 For the petitioners, pride in the Sephardic heritage, customs, and Ladino language was at work. But it was also a quest for the proverbial insurance policy, the “Plan B,” in case governments antagonistic to the Jews came to power. The rise of Recep Erdoğan in Turkey, Hugo Chavez and then Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela, radical Islamist terror attacks in Europe and the Middle East during periodic flare-ups of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—such developments kept alive the Sephardic desire for “papers” from Iberia.

Spain’s Law

That desire was supported in Spain by the Federación de Comunidades de Judíos de España (FCJE). Isaac Querub Caro, the Federation’s president at the time, said he and a colleague, concerned about the plight of the Jews in Turkey and Venezuela in particular, had approached Ruiz-Gallardón, of Mariano Rajoy’s Popular Party-led government, seeking a safe harbor for Turkish and Venezuelan Jews, whether Ashkenazi or Sephardic. According to Querub Caro, the justice minister responded that the request was too ambitious, so the FCJE scaled back and urged a grant of Spanish citizenship to the Sephardim.6 Such an act would bring historic reparation and reconciliation; also it would improve Spain’s international image by showing, at least ostensibly, that Spain was overcoming an antisemitism of which vestiges remained well into our time. The FCJE was to manage the collection of proof of ancestry, as set forth in the legislation that Ruiz-Gallardón and other deputies guided through the parliament. Not being a specifically Sephardic body, the FCJE would contract with various Sephardic groups outside of Spain to check applicants’ bonafides.

On the government side, the lead actor was the Directorate General for Registers and Notaries, an arm of the Justice Ministry. The DGRN gathered all applications and assigned notaries around the country to handle them. Spain’s citizenship offer was not open-ended. The Spanish notaries had to receive the applications by a deadline, written into the law, of October 1, 2018. The government expected, based on the FCJE’s projection, about 90,000 people to apply. This underestimate (the number ended up exceeding 132,000, according to the British newspaper the Guardian) led to the extension of the application deadline by a year, as contemplated in the law.7

Canadian attorney Doğan Akman, in an analysis of the law that was published in these pages in 2016, noted that, under the previous legal regime, aspirants to Spanish citizenship (of whatever religion or ethnicity) were able to “pursue their applications through the local Spanish consulates of the country in which they resided.” In contrast, “the process under the new law is wholly computerized, managed and administered centrally in Spain by the DGRN.” A collision of legal provisions, pre-2015 and post-2015, was set up that would contribute to the bogging down of the process. One legislator, Jon Iñarritu García of the Basque Country Unite Party, said during the vote on the bill that he welcomed Spain’s attempt to make amends for its injustice. But, he complained, “Why is it not possible for applicants to perform the required procedures at Spanish consulates abroad? And why do they have to go before a notary?”8

The time limit in the final version of the bill was criticized by Iñarritu García and others as ungenerous; but on the other hand, the final version widened the potential applicant pool in ways favored by the FCJE: A requirement that those seeking citizenship reside in Spain was waived, as was the country’s prohibition of dual citizenship. (The demand for residency would not go away in the succeeding years, as we shall see.) Those who objected to the bill’s particularistic goal—the deputies of the United Left bloc in parliament— also influenced it. Ruiz-Gallardón’s colleagues on the other side of the aisle asked, what about the descendants of the Arabs and Moriscos (Christians who had been forced to give up Islam)? They, too, were persecuted by the Inquisition. Thus were a Spanish language test and a civics test added “to avoid anyone’s saying that this was a privilege” (Ruiz-Gallardón’s words) conferred upon a single ethnic/religious group. Ruiz-Gallardón, himself a descendant of the Sephardic composer Isaac Albéniz, did not consider the language and civics tests to be much of a concession.9 A second way in which the drafters tried to ensure non-discrimination was to make citizenship available to people of Sephardic descent whether or not they practiced Judaism, or another faith, or no faith.

These features of the legislation, even if meritorious in themselves, attenuated the idea of repairing a breach with Jews who had kept their connection to Sepharad despite the injustices done to their people. Applicants have said as much. Karen Gerson Sarhon, a Turkish Sephardic Jew who attained Spanish nationality under the 2015 law, pointed out that her family, like other Turkish Sephardim, had preserved Ladino “since the 15th century and this should have been enough.” In her contribution to a multi-author volume about the law, Sarhon wrote that “this law was passed as a mea culpa. If that is the purpose, they should not have demanded the [Spanish language] exam.” She said many Turkish Sephardim she knew, to avoid this chore, switched from seeking Spanish citizenship to seeking Portuguese citizenship.10 (Portugal’s law does not entail language or civics exams. On the question of religion, though, the Portuguese counterpart was drafted with a similar intent to avoid religious discrimination.)

Putting the government’s cultural outreach arm, the Cervantes Institute, in charge of administering the language and civics tests added yet another decisionmaker to the process along with the FCJE, the Sephardic rabbis and experts around the globe, and the government’s notaries. The set-up was complex. It was long on requirements and short on accountability for those who had set them. Applicants were supposed to be able to navigate the process without hiring an attorney but this proved far from the case.

Not long after passage, as the applications piled up, justice ministry officials realized that the ministry needed to give itself more time to get through the paperwork of the people waiting in a very long queue. When the coronavirus pandemic hit, there were further delays, with those who had met the final submission deadline of October 1, 2019, facing hurdles when trying to schedule and take their language and civics tests, or make their required trip to Spain to sign documentation in the presence of their assigned notary.

Ruiz-Gallardón’s successor as justice minister, Rafael Catalá Polo, had already given assurances, when the law was new, that the ministry would be “flexible” in its treatment of applications and would take action to alleviate bottlenecks. Akman quotes Catalá as having said that “ ‘the government will accept whatever type of proof which reasonably establishes the applicant’s [Sephardic] origin,’ and ‘will do everything possible to facilitate the presentation of the application through consular offices.’ ” This announcement of a broad executive power to step in made it seem as if the profusion of evidentiary and other requirements (such as electronic filing directly to the DGRN and the in-person appearance before the notary) might be optional at least in some cases. As Akman archly put it, “What was then the purpose of setting up such an elaborate and expensive two-tier adjudicatory system? Patronage for the notaries?” He went on: “What will happen if the . . . succeeding government does not subscribe to the current Minister’s approach and insists on having the process operate strictly by the book?”

It was a prescient question. Flexibility had been the order of the day—and nary an applicant failed to be awarded Spanish nationality—until the government changed hands. In June 2018, the Socialist Party (PSOE), led by Pedro Sanchez, was elected. According to María Martín of El País, Spain’s leading daily, the year was not yet out before the justice ministry got a police alert that “warned of the existence of a criminal organization and possible fraud” in the system. Martín’s article, which came out in 2021, said the alert had reached Madrid “from a Spanish embassy in a Latin American country.” Bogus applications were being sent through the system, was the implication.11

What illegalities were being committed never became clear. More clear was that the Socialist government was trying to shift from loose to strict construal of the 2015 law. This we can see from a circular12 that the head of the DGRN in Madrid sent out to the notaries, whose offices dotted the country. Parsing the bureaucrat-ese in this circular, which is dated October 29, 2020, is not easy. But one gleans that the crackdown was an attempt to 1) stop applicants’ shopping around for a synagogue or Sephardic group with low evidentiary standards; 2) end the acceptance of “a mere reference to” family surnames unaccompanied by genealogical research; 3) stop applicants’ filing through Spanish consulates rather than the DGRN and 4) make sure applicants were appearing in person before the notaries, as required. The third and fourth points could be related. Consular applications, as mentioned, were part of the previous legal regime; one may speculate that notaries, or others, were reverting to the old way of doing things.

As for fix number two, questions around certifying Sephardic bonafides had been gathering steam, as the DGRN under Pedro Sanchez’s government began to take seriously genealogical sticklers’ objections to how certification was being done. Some synagogues and Sephardic organizations relied on “name reports.” These are lists of family surnames that were common among the Iberian Jews—but also, in many instances, common among all Iberians, thus limiting their utility. The standard-setting Sephardic Genealogical Society considers surname lists genealogically dubious and unethical to use for certification purposes. “We need archival evidence, carefully traced back, generation by generation,” said David Mendoza, a British genealogist and the president of the Society.13 Some applicants were able to become citizens with weak genealogical support, relying on name reports and physical artifacts such as ketubahs (marriage contracts), family photos, burial records, and identity papers passed from generation to generation.

Sara Koplik amassed such materials for the Jewish Federation of New Mexico, which helped about 20,000 people to apply for Spanish citizenship. Half of the applicants it certified were turned down. In a recent interview, Koplik blamed governmental rule-changes in midstream for the rejections. An applicant’s having to be vetted by a Sephardic authority located in his or her “area,” she said, came to be interpreted narrowly. The non-U.S. applicants whom the group was assisting, or even U.S. applicants outside of the southwestern United States, suddenly got tripped up, Koplik said.14 Applicants interviewed at the time by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency also cried foul. Reported the JTA’s Julia Gergely: “Many applicants have been asked to provide more in-depth genealogy charts, and some face bureaucrats’ insistence that the ‘special connection’ donation to the Spanish economy must have been made before the law was announced in 2015.”15

Mendoza of the Sephardic Genealogical Society challenges the idea of a crypto-Jewish enclave in New Mexico, which was the northernmost seat of Spanish power in the New World. At the time of the DGRN’s crackdown, he posted on the Times of Israel’s blog that “The Jewish Federation of New Mexico believes that some local New Mexicans have Sephardic ancestry and so issues confirmatory letters for immigration purposes when some other congregations certainly would not. In an apparent act of cultural appropriation, they have taken to calling their local client population ‘Sephardim’.”16

Mendoza also suggested that the Sephardic heritage program through which applications were being evaluated had made the organization’s budget grow suspiciously flush. “The federation has sat by idly and allowed all applicants to have their reputations tainted with crazy allegations of fraud while they refuse to stand up to those allegations,” a disappointed applicant named James Ord told the JTA’s Asaf Elia-Shalev.17

That members of the Hispano community of New Mexico, present well before the founding of the United States, had Spanish conquistadors among their progenitors is well-known. Five hundred years ago, some conquistadors were New Christians, and hence people of Sephardic background.18 Whether the very slight indications, such as certain ways of slaughtering meat, or other secret family traditions—which the modern individuals themselves did not link to a Jewish ancestry until recently—can be counted as evidence is a hotly contested subject. It, along with the use of name reports, and the charges of corruption, helped bring on the ejection of the Jewish Federation of New Mexico from Spain’s nationality-concession program.19

According to Koplik, crypto-Jewish New Mexican claims were not accepted by the government but neither were some genealogically-based applications of descendants of converso New Mexicans. She said that by searching the records of the Inquisition that were kept by the Catholic Church, “converso New Mexicans could prove seven hundred years of genealogy” and yet their documentation still “wasn’t considered enough.” In trying to clean up a flawed process, the Spanish government may have thrown out genuine claims to Sephardic ancestry.

The reining in of what was, after all, supposed to be a temporary program was abrupt. The infractions listed in the circular sent to the notaries were grounds for disqualification. In due course, El País and the New York Times reported that a wave of thousands of rejections of applications began in the spring of 2021. Up to that point, or a little later (Nicholas Casey’s article came out in the Times in July), some 34,000 people had gained Spanish citizenship under the law but around 3,000 applicants had just had their applications rejected. “At least another 17,000 people have received no response at all, according to government statistics,” wrote Casey. “Many of them have waited years and spent thousands of dollars on attorney fees and trips to Spain to file paperwork.” Remarkably, “before this year, only one person had been turned down, the government said.”20

At the very least, its civil servants had been operating amid a confusing set of rules. Notably, the corrective circular had said documents needed to be of the prescribed type and be received through the proper channels, but there was no reminder to be vigilant against documents that were fraudulent. Nothing was said in it about the mysterious police alert from 2018—the news of which came three years after the fact, at a time when the justice ministers were taking a dramatic action that they were eager to justify. A Sephardic Horizons request for comment from the former DGRN official named at the top of the circular was not answered. A Spanish lawyer who has helped clients apply for citizenship based on their Sephardic descent told Sephardic Horizons that, as far as he is aware, no investigation pursuant to the police alert ever came to light.

In the fall of 2021, the FCJE announced that it had wrapped up its work. Neither it nor the Spanish justice ministry provided, when asked, an update of how many of those in limbo (the “no response at all” group from Casey’s article, all of whom, presumably, met the application deadline) had by then gotten a verdict. Among those stuck in the pipeline or rejected outright were Venezuelan applicants who spent a lot of time and money seeking the ability to expatriate from a country in dire straits. Marcos Tulio Cabrera, who established the Association of Spanish-Venezuelans, told Casey that he spent $53,000 on nine family members’ applications for nationality, with four rejected and the rest in limbo.

Cabrera might want to re-enter the fray—then again, he might not—but in any case, there came the news, in late 2024, that the Federation had not wrapped up its work.21 According to a Spanish attorney in an online help session held by the Centro Cultural Sefarad in Argentina, the FCJE had revamped its digital intake system and was ready to again ask the justice ministry to consider bids for nationality by reason of Sephardic ancestry. Applicants under the 2015 law who were in limbo22 could jumpstart their cases provided they now sought certification from the FCJE itself. Confirmation of this new bureaucratic dawn was not forthcoming from the Federation. On its website,23 the requirements no longer (as of December 2024) included the language and civics tests to which Ruiz-Gallardón acceded a decade ago to mollify legislators worried about fairness. (Those who endured the rigamarole of the tests might, at this pass, dispute the fairness of removing the hoops they had to jump through.)

Portugal’s Law

Portugal’s situation isn’t identical to Spain’s but there are similarities. There never were language or civics exams in Portugal’s law. No deadline was written into it, although some lawmakers would come to assert that its purpose had been fulfilled, and it should be repealed. The Portuguese authorities were swamped with more applications than they expected, which overwhelmed an inadequate workforce, as happened in Spain. Portugal’s initially lavish approvals slowed when problems hit the system, as in Spain. The Portuguese made ungainly attempts at amendments to fix things on the fly as did the Spaniards. And, as in Spain, the authorities lurched into gear after losing trust in entities initially given the authority to certify Sephardic lineage.

Certification is bifurcated in Portugal, to uniquely dysfunctional effect, between the country’s main Jewish organizations: the Comunidade Israelita de Lisboa (CIL) in Lisbon and the Comunidade Israelita do Porto (CIP) in the northern city of Porto. The CIL, centered around the Shaare Tikvah Synagogue, and the CIP, centered around the Kadoorie Mekor Haim Synagogue, are rival gatekeepers, each with its own criteria for authenticating Sephardic ancestry and its own interpretation of the 2015 law. An aspirant to citizenship by reason of Sephardic lineage can choose to send his or her documentation to either one. Hence it was not geographical considerations (homing in on where in Portugal one’s forebears lived) that created the bifurcation. CIL is older and is in the nation’s capital and most important city, where final decisions on citizenship are made (by the justice ministry, as was the case in Spain). CIP, which bills itself as “the only powerful Jewish community in Portugal,”24 prides itself on its nurturing of Judaism in Portugal, a land where it had once flourished. In the 1930s, the Kadoorie congregants, led by the synagogue’s founder Arturo Carlos de Barros Basto, set out to “help descendants of New Christians return to normative Judaism.”25

The Porto congregation looks less to genealogical records, and more to halakha and the collective knowledge of Sephardic family histories of the worldwide Sephardic rabbinate.26 The Lisbon congregation is strictly genealogical in its approach, does not involve its rabbi in the process, and is less interested in the religious status of any Sephardic progenitor or progenitors found on an applicant’s family tree. The need, moreover, to uphold nondiscrimination laws—that is, to treat all of the applicants themselves equally as to religious status—is kept in mind by CIL but evidently not by CIP.

These differences mirror the lack of unanimity, within the Sephardic world, about the purpose of the Iberian nationality-concession laws. Neil Sheff, an American lawyer and president of the board of directors of the Los Angeles-headquartered Sephardic Education Center, has nothing but praise for the Porto congregation. Sheff said in an interview that CIP certified his family and some 70 clients for whom he has submitted applications under the 2015 law. Most in this group, including the Sheffs, have yet to gain governmental approval. In his opinion, CIP’s vetting adhered closely to the reparative spirit of the law, whereas CIL, with its time-consuming genealogical and archival research, was reaching back to remote generations to the benefit of applicants who are personally unconnected with Sephardic Jewish ways. (Sheff describes himself as one of the last of the Ladino-speakers.)

The Sephardic Genealogy Society makes no bones about the difficulties of chasing after old documents. Down the years, the upheavals and dislocations of war, the destruction wrought by floods, fires, and simple human disorganization, all burden the genealogist’s task. But it’s a task upon which the Society insists.27 On behalf of “the Nação Portuguesa, the Western Sephardic diaspora,” the Society criticized CIP for “apparently [finding] evidence of Sephardic ancestry in families we had assumed belonged to Ashkenazi, Mizrahi or other Jewish sub-groups”—and for for acting hastily, without compiling an unbroken chain of birth, marriage, and death certificates and the like.28 Sheff, too, said some who have a family tradition of considering themselves Sephardic lack a valid claim. He said he declined to handle the cases of several such hopefuls, and mentioned Persian Jews in particular. But to Sheff, it stands to reason that verification could well be quick. Proving that grandparents or parents transmitted the language, religious rites, and customs of Sepharad is a matter, not of painstaking research, he said, but of submitting family documents, memorabilia, and correspondence, some of which would be in Ladino, and having rabbinical authorities vouch for applicants’ lifelong membership in Sephardic synagogues and cultural associations.

If divergent legal interpretations and methods on the part of the Porto and Lisbon congregations were not enough to gum up the works, the entry into this story of the late Russian dissident Alexei Navalny two months before Russia invaded Ukraine really threw in a spanner. But let’s back up a bit. In 2020, the oil tycoon Roman Abramovich received Portuguese citizenship, having had his Sephardic ancestry certified by CIP. Abramovich, who grew up in the northern part of the Soviet Union and built a fortune as one of Boris Yeltsin’s favored entrepreneurs after the USSR’s fall, already had Israeli as well as Russian citizenship. This former owner of a British soccer team, who was reputed to be close to Vladimir Putin, in 2021 added a Portuguese passport. Navalny, from his detention cell in Russia, cried foul on social media: The man he called “one of Putin’s wallets” had offered “some bribes and [made] some semi-official and official payments to end up in the EU and Nato.”

“Putin’s Portuguese” Are No Match for the Polícia Judiciária

Scrutiny had arrived. Up to that point, the justice ministry had declined some 300 applications, with approvals by the ministry numbering in the tens of thousands (estimates vary widely from source to source). The foreign minister, Augusto Santos Silva, called a press conference to respond to Navalny. He said, “The idea that Portuguese civil servants carry suitcases of money is insulting.” Yet someone must be carrying suitcases of money, thought reporter Paolo Curado. Curado’s story in the Lisbon daily Público was marked “Exclusive” and headlined: “Comunidade Israelita do Porto Has Millionaire Profits with Portuguese Nationality.”29 The story’s sub-headline zeroed in on a deputada who had coauthored the 2015 law who was also the aunt of one of the Porto synagogue’s officers. According to another Lisbon daily, Correio da Manhã, there had been an anonymous complaint floating around parliament that hinted darkly about the genesis of the nationality-concession law.

The Público investigation did not produce a direct tie to Abramovich. It didn’t need to, contended Natasha Donn, the political reporter for an expatriate website called Portugal Resident. Donn, who referred to the nationality concession as “Portugal’s Sephardic Jew amnesty,”30 said it was the swiftness of Abramovich’s certification (under two hours, reported Willem Marx in Vanity Fair) that justified delving into CIP’s practices as a whole. Just look, said various commentators, at how many new amenities and social services the Porto congregation had recently built—prima facie evidence of selling its imprimatur to fake Sephardim. CIP president Gabriel Senderowicz, a Brazilian Sephardic Jew who came to Portugal in 2017, defended his institution, arguing that, if the gleam of prosperity had fallen upon the Comunidade Israelita do Porto since the law’s passage, it wasn’t from corruption but from philanthropic contributions and the administrative fees (€250 per applicant) that accrued, legitimately, to the Porto congregation as a result of the popular 2015 law.31

What was now being called “the passport scandal” prompted the government to begin investigating the Porto congregation. No sooner had Operation Open Door, the justice ministry’s name for the investigation, commenced than Putin sent the Russian military over Ukraine’s border. The Russian invasion of February 24, 2022 brought international sanctions on Abramovich and other Russian Jewish billionaires––several of whom proved their Sephardic ancestry as well, and were now citizens of Portugal. With their Portuguese papers, they could move about the EU countries in defiance of the British and EU sanctions. (Abramovich, who got involved in peace negotiations between Kyiv and Moscow, and who worked on a prisoner swap that failed to save Navalny but secured freedom for westerners imprisoned in Russia, has denied monetary ties to the Kremlin and is in court to reverse the sanctions.32)

As the world looked on in horror at Russia’s bombing of Ukrainian cities, the media drumbeat grew louder, with the Spanish daily El País writing of “the trafficking in Portuguese passports” and the influential Portuguese weekly Expresso warming to the topic of “Putin’s Portuguese.”33 Then on March 10, 2022, officers of the federal Polícia Judiciária went to the airport north of Porto to arrest Rabbi Daniel Litvak, the certifier of Abramovich. As recounted in Vanity Fair, Malkiel Litvak, the rabbi’s son, “watched in shock as more than a dozen men halted traffic, seized bags, and bundled his father into a vehicle, speeding off without explanation.” The Polícia Judiciária also raided the synagogue and offices and homes of CIP directors. “The eventual charges against Litvak included document forgery, influence peddling, and money laundering—and he was arrested, he was told, based on an anonymous tip that he was trying to leave the country,” wrote Willem Marx. Litvak was indeed trying to leave the country. A commuter between Porto, where he served as the Kadoorie Mekor Haim Synagogue’s chief rabbi, and his home in Ashdod, Israel, he was boarding a flight with his son to get home to his wife and his other children as he had done for years.34

The grim humor in the state’s chasing down a rabbi who took part in its reparation for past ill-usage of the Jews was lost on the leaders of Operation Open Door. Also, apparently, on the Sephardic Genealogical Society, which inveighed against Rabbi Litvak by name and called for “custodial prison sentences” should “anyone be found guilty” of criminal offenses in l’affaire Abramovich.35 At least in our day and age the rabbi could have his day in court. In September 2022, the Lisbon Court of Appeals ruled that prosecutors and police had failed to substantiate the charges. “There is nothing in the file that tells us that these payments were of criminal origin,” read the decision. “In which naturalization processes,” the judges wondered, “did the appellant falsely attest that an applicant was a descendant of Portuguese Sephardic Jews?” The charges were, as they say in the legal field, tainted by vagueness. “How does one defend oneself from generalities?” the judges asked rhetorically.36

Meanwhile, a report in the Guardian mentioned an official inquiry into “the use of the citizenship law” that was supposed to lead to “disciplinary proceedings against employees at Portugal’s Institute of Registries and Notary, which provides nationality and passport services.”37 Where that inquiry ended up is unclear. Follow-through has not been a Portuguese specialty any more than it has been a Spanish one. Government and media are similar in that regard. Público’s crusade petered out, with Curado, its investigative reporter, offering wan comments to Israel’s newspaper of record: “Curado, who reported on the investigation, told Haaretz that while working on it he found no indication of criminal activity or irregularities on the part of the board of directors of the Porto Jewish community, which has major influence in the decision to grant citizenship. However, he said that the entire process of examining the requests for citizenship of expellee’s descendants lacks transparency.”38

Six days after the arrest of Rabbi Litvak, the Porto congregation announced that it was quitting its verification job in protest. All applications then went to Lisbon; with CIL having to take up the slack, its already long delays got longer. The situation did not turn out to be permanent, for by early-to-mid 2024, CIP resumed processing applications. The justice ministry has not formally closed its investigation of CIP and its chief rabbi; and yet the Porto congregation left the process of its own volition, and re-entered the same way. The firmness of the ministry’s view that it is a criminal enterprise is in doubt.

Definitions

When the Sephardic Genealogical Society criticized CIP for “apparently [finding] evidence of Sephardic ancestry in families we had assumed belonged to Ashkenazi, Mizrahi or other Jewish sub-groups,” it wasn’t saying that that in itself was contrary to Portugal’s law. That law, much to the Society’s dissatisfaction, accommodates a link to Sepharad that is indirect. The “overwhelming majority”39 of those granted nationality under Portugal’s law fall into this indirect category, being mostly from the Balkans, the Middle East, and North Africa. Rabbi Litvak confirmed this when fielding pointed questions about Abramovich from the Jornal de Noticias (before the judicial police drove up from Lisbon and took him away). He said the law accommodates “a tradition of belonging not to Portugal but to a Sephardic community of Portuguese origin, in Tangiers, Tunis, Cairo, Istanbul, Antwerp, etc.”40 He was pleasantly surprised by the leeway. Indeed the Lisbon congregation is no different in this respect; CIL, too, approves the bonafides of people who have proven lineage within the “larger universe of Sephardic diaspora.”41 But again that leeway, or that larger universe, will not find affirmation from the Sephardic Genealogical Society.

One city whose Sephardic community Abramovich laid claim to in his application was Hamburg, where a small number of western Sephardim or Nação Portuguesa, as the Society calls it, settled circa 1590. Sephardim did make it to Central and Eastern Europe, including modern-day Germany, Poland, and Lithuania, to which Abramovich has clear ties in that his grandparents were Lithuanian Jews. But again, that migration often was circuitous. (Much was from the Ottoman areas as the Ottoman Empire spread westward.) “While it’s certainly true,” said genealogist E. Randol Schoenberg during one of the Society’s online meetings, “that non-Ashkenazi Jews and Jews potentially of Sephardic origin entered Eastern Europe, we have yet to find a single genealogically provable tree that goes back to Iberia for any of these European Ashkenazi families.”42

Is the Russian oil tycoon’s claim solid? A trove of documents supporting it was released on the internet anonymously in mid-2022. Its contents were unconfirmed, as the journalists who reported on it stressed. Regarding the surname question, the dossier is less than convincing, including as it does a table entitled, “A Large Selection of Sephardic Jewish Surnames,” with not only Abramovitch and Abramowitz, but Anderson and Andrews, on it; and not only Leibowich and Leibowitz (the surname of an Abramovich grandparent), but also Littleton, Long, and Lowell. A passage in a document about Abramovich’s antecedents matches nearly verbatim a passage in a legal brief that Senderowicz, CIP’s president, submitted to a European Union court (the congregation is suing the Portuguese government to restore its good name), thus it’s likely the dossier came from CIP.43

As we have seen, the Sephardic Genealogical Society eschews name reports. The Portuguese law does not, nor does its Spanish counterpart, though in both cases surnames are not sufficient in themselves. The Society maintains that “[t]he vast archives of the period show virtually no involvement of the Western/Portuguese Sephardic diaspora with the Jews of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth where Mr Abramovich’s ancestors are assumed to have lived.”44 Apart from the matter of the wiggle room in the 2015 law, it’s a fair point as far as it goes. And, to be sure, the fast-tracking of Abramovich calls to mind earlier examples that make one’s eyes roll, of warp-speed Iberian citizenship for magnates—see the Spanish government’s “surprisingly expeditious”45 granting of Spanish nationality to the late Turkish American industrialist Erol Beker. We can hope that Roman Abramovich’s Hamburg pedigree is as real as his Lithuanian pedigree. On the other hand, it seems to be water under the bridge. For even if his Sephardic certification were specious—even if he were stripped of it, as some have demanded—his citizenship status would probably be unaffected. Mindful of its membership in the European Convention on Human Rights, Portugal keeps to the convention’s governance standards by setting a high bar for the revocation of citizenship once granted.46

A much less equivocally pedigreed big wheel gained Portuguese nationality as soon as the Sephardic law passed in 2015. The genealogists of the Lisbon congregation locked down the lineage of Patrick Drahi, the French-Israeli media mogul, back to his ancestors who were expelled by Manuel I in 1496. Nonetheless, six years on, when Abramovich’s bonafides were questioned, so were Drahi’s. This was at a time when the latter’s firm, Altice, was vying for ownership of Portuguese media properties. The judicial police investigated Drahi “for allegedly having intervened” in l’affaire Abramovich; or, as Expresso breathlessly put it, “Patrick Drahi is defendant number two in Abramovich's naturalization case.”47 Drahi, the owner of Israel’s i24 TV channel and telecom companies around the world, made the cover of the newsweekly Visão when he was a newcomer to Portugal. The Visão profile of 2017 mostly discussed Drahi’s corporate ambitions. His interesting Sephardic Jewish heritage was touched upon, though, as was his reputation as an “ascetic capitalist” who wore a watch made of plastic, and his quip to U.S. media that he paid the lowest salaries he could to the executives who worked for him.48

The Sephardic Genealogical Society protested the investigation of Drahi and “the unpleasant tint” of the reportage about him. Senderowicz of CIP also raised objections. It was a rare point of agreement between the Society and the Porto congregation. As for the Lisbon congregation, the judicial police prevailed upon CIL to open its Drahi files for inspection.49 Its certification of this son of the Nação Portuguesa must have passed muster; the media attention receded.

Iberian Passports for Israelis

Israelis in general have flocked to the nationality-concession programs. They are well-represented in Spain’s; in Portugal’s, they constitute the largest national contingent to apply. In fact the Sephardic self-conception of many Israelis is not given a lot of credence by the Sephardic Genealogical Society. The term “Sephardic” is used in Israel, according to David Mendoza, mostly as a catch-all to denote anyone who is not Ashkenazi.50 In any case, Israeli law firms did a land office business assisting clients with applications, which have totaled well over 40,000 in the last couple of years, according to Yariv Kav of The Portugal News. A Tel Aviv resident interviewed by Kav told him that carrying an Israeli passport is “restrictive.”51 Israel’s citizens face exclusion from some countries.52 The official no-go list got longer recently with the addition of the Maldives, which banned Israeli citizens in condemnation of the Israeli Defense Forces’ military campaign against Hamas in Gaza.

Be that as it may, few Israelis who acquire a Portuguese passport move to Portugal. This should remind us of the “Plan B” imperative, which—today, as immemorially—is to secure the possibility of going to another place but not necessarily to go there. In a humanitarian gesture in the immediate aftermath of Hamas’s attack on southern Israel on October 7, 2023, the Portuguese government declared that it would expedite the processing of Israeli applications. After it received a petition from former deputado Ribeiro e Castro on behalf of one of the Israelis taken hostage by Hamas—Ofer Calderón, who is still captive in Gaza—Calderón was summarily granted citizenship. Simultaneously, what had been a series of parliamentary and ministerial attempts to repeal the law, or at least stiffen it with residency or other requirements, finally succeeded. The long-simmering gripe of the Portuguese—in obedience to that other age-old imperative, sefarditismo económico—was that this rampant “citizenship for mere convenience” must not be allowed to continue. Beneficiaries of the 2015 law needed to live in Portugal or at least visit the country frequently.

It was as if “the passport scandal” in Portugal had revealed two faces: one that resented being set upon by knaves, another that felt dissatisfied with them for making themselves so scarce. Under amendments achieved in 2022 and 2024 by the ruling Socialist Party and allied parties on the left, the legal regime begun in 2015 survived, but applicants would in future need to demonstrate Sephardic descent and either time spent in Portugal or business or real estate investment there. A three-year residency requirement is now in the Sephardic law (a compromise, for the usual residency requirement is five years) but has not yet come into force. Also added was an “evaluation commission” on which representatives of the Lisbon congregation and the Porto congregation, CIL and CIP, would serve alongside scholars and government officials. Presumably, with the advent of this commission, the verification work of the two Jewish communal groups would be supervised by others.

The reformers of the law also wrote a provision that required proof of inherited property in Portugal—an especially galling demand to make of people whose ancestors had their homes or land confiscated by the Inquisition. Although that controversial provision was at one point withdrawn, it appears to have survived as an optional way to demonstrate one’s ties to the country. In an effort to ward off future Abramovich-style embarrassments, lawmakers added language about vetting applicants who might pose a national security threat. This was needed, in the words of one Portuguese immigration consultant, because the decision to concede or not concede nationality “directly affects the national defense and homeland security of Portugal and, on a greater scale, the European Union.” The law “suffers constant alterations,” she added, as a “reflect[ion of] how each government felt about this kind of citizenship application.”53

An Uncertain Future

Those whose time and money have not yet borne fruit are doing their best to keep up with the mutations. In mid-2024, the Sephardic Genealogical Society held an online session for applicants and prospective applicants. The former sought assurances that they were grandfathered in. The latter were urged to apply before the bar was raised with the residency requirement. Isabel Comte, a Portuguese attorney, told the attendees that she saw an advantage in that it might take a year, or more, for the residency requirement to kick in—or it might even be put off indefinitely by the right-of-center parliamentarians who had opposed it, if they were to win the next election. (They did win.) Those whose applications had been languishing for years shared their Bleak House-like tales of procedural paralysis and confusion about what to do next. A lot of displeasure was directed at the Lisbon congregation, though it is the better-regarded of the two verifiers. CIL was described as “in disarray” whereas CIP, having ended its labor strike, as it were, was apparently working efficiently—if persisting in its religiously discriminatory ways. As one attendee put it, accurately if not at all sympathetically, the Porto congregation “just wants more Jews” in Portugal. How reprehensible a goal is that, really, in a modern democracy with a Jewish past whose current Jewish population is only about 5,000?

There was much puzzlement over the Lisbon genealogists’ wasting a lot of time and effort building each and every genealogy from scratch, even if an applicant had a consanguine relative whose Sephardic ancestry was already established. One would assume that people consanguineously related to a certified person would have a leg up and be certified relatively quickly. A former CIL employee who spoke to the group, historian Teresa Santos, reported that her former colleagues at CIL were exhibiting undue caution, and reinventing the genealogical wheel, out of worry that their certifications might be questioned (recall the Drahi dragnet) and they didn’t want to wind up in trouble like the Porto rabbi.54

To enter the bureaucratic maze now was presented as complicated but doable. Some at the meeting expressed interest in applying. Nor was plucking success from the mass of applications that sit in the Conservatória (the justice ministry’s records repository) impossible, according to Comte, especially if you litigate. Comte held out hope for the evaluation commission that is supposedly being organized. She believed the Portuguese government’s taking firmer control might cure some of the bureaucratic hiccups and curb religious discrimination in nationality-concession for Sephardic descendants.

Immigration attorneys in Spain, too, are convinced they know that system’s quirks well enough to get it to cough up nationality concessions. Luis Portero, the Spaniard who gave his advice during the help session of the Centro Cultural Sefarad, told the group that although the 2015 law “terminated,” the many left in limbo, with their documents stuck either with a notary somewhere in the country or at the justice ministry in Madrid, could still find resolution. There was recourse, too, for those who mounted legal appeals only to have their appeals run aground in the court system.

The government now trusts no verifier except the Federación de Comunidades de Judíos de España, according to Portero. And the FCJE has improved its digital connection with the government, he said. The applicant compiles another set of the documents that he or she sent in before, including genealogies, and uploads them to the Federation website. Then, certification; then, the justice ministry responds . . . and, bingo. That’s the idea, anyway. In dribs and drabs, those notaries with whom applicants were obliged to meet on Spanish soil under the legal regime of 2015 continue to emit approvals. But one can obviate the notaries now, Portero seemed to say; they’ve been taken out of the electronic loop. Very much back in the loop (no doubt to the satisfaction of such legislators as Iñarritu García) are the Spanish consulates around the world. Consular officials are able to send an applicant’s FCJE certificate to the central government electronically. Even rejected applications stand a chance of being turned around if this new method is used, Portero insisted.

A couple of pre-2015 alternatives came back, as well. The first is that Sephardic descendants can qualify for Spanish citizenship by residing in Spain for two years (the usual residency requirement is 10 years). The second is the age-old, the coveted, carta de naturaleza, which comes—if it comes—via royal decree. Portero called it “the interesting route” for a Sephardic descendant, if that individual is willing to petition King Felipe VI, who, acting through his Council of Ministers, and “following criteria of political opportunity,” bestows his favor upon an aspiring citizen of the realm at his own discretion. My, but it brings history alive, and in an uncomfortable way, for Jews and the descendants of Jews to be hoping and waiting, waiting and hoping, for a monarchic gesture of sufferance.

1 Lauren Weiner is a freelance writer whose articles and reviews have been published by many U.S. newspapers, journals, and websites including the Wall Street Journal, Commentary, National Review, Real Clear Religion, the Weekly Standard, Modern Age, the New Atlantis, American Purpose, the New Criterion, Law and Liberty, the National Interest, the Washington Times, and the Baltimore Sun.

2 Gerber, Jane S., The Jews of Spain: A History of the Sephardic Experience (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), pp. 25, 26, 208, 209, 213.

3 The concept of sefarditismo económico was explored by the late Doğan Akman in his essay entitled, “Spain’s Correction of Her ‘Historical Mistake and Injustice’: Spanish Citizenship for the ‘Sefardíes’: An Assessment,” Sephardic Horizons, Vol. 6, issues 3-4, Summer-Fall 2016. All quotations of Sarah Abrevaya Stein are from her article, “Passport Sepharad,” Jewish Review of Books, Summer 2016. See also Kandiyoti, Dalia, and Rina Benmayor, Reparative Citizenship for Sephardi Descendants: Returning to the Jewish Past in Spain and Portugal (New York: Berghahn Books, 2023), p. 312.

4 García, Celia Prados, “La Expulsión de los Judíos y el Retorno de los Sefardíes como Nacionales Españoles: Un Análisis Histórico-Jurídico,” Actas del I Congreso Internacional sobre Migraciones en Andalucía, Universidad de Granada, 2011. ISBN: 978-84-921390-3-3

5 Lisbona, José Antonio, in multi-author collection, Cuánto os Hemos Echado de Menos: Concesión de la Nacionalidad Española a los Sefardíes (Madrid: Nagrela Editores, 2023), pp. 111 and 113, ISBN: 978-84-949801-4-5; Akman, “Spain’s Correction of Her ‘Historical Mistake and Injustice’”, op cit.

6 See the comments of Isaac Querub Caro in a panel discussion held by the Centro Sefarad-Israel in Madrid, August 28, 2023. The YouTube video of the event, entitled, “Presentación del libro «Cuánto os hemos echado de menos»”, is an hour and 24 minutes long. At the 25:30 mark, Querub Caro, with Ruiz-Gallardón sitting on the panel with him, recounts the meeting between the two of them in 2011.

7 Jones, Sam, “132,000 Descendants of Expelled Jews Apply for Spanish Citizenship,” The Guardian, October 2, 2019.

8 Akman, “Spain’s Correction of Her ‘Historical Mistake and Injustice’”, op cit. For the statement of Diputado Iñarritu García, see Diario de Sesiones del Congreso de los Diputados: Pleno y Diputación Permanente, Núm. 287, June 11, 2015, p. 11.

9 See Q and A with José Antonio Lisbona and Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón, Cuánto os Hemos Echado de Menos, pp. 191-2.

10 Sarhon, Karen Gerson, in Cuánto os Hemos Echado de Menos, p. 263.

11 Martín, María, “Thousands of Sephardic Applications for Spanish Nationality Denied Following Fraud Alert,” El País, August 20, 2021.

12 Ministry of Justice of Spain, Directorate General for Registers and Notaries, October 29, 2020, “Circular de la Dirección General de Seguridad Jurídica . . . en Materia de Concesión de la Nacionalidad Española a los Sefardíes Originarios de España”

13 Sephardic Genealogical Society video on Youtube entitled, “Ashkenazim with Sephardic Ancestry?”, November 14, 2021. The video is an hour and 22 minutes long. Mendoza’s words are at 14:30. The Society’s code of conduct can be found at https://www.sephardic.world/code-of-conduct.

14 Telephone interview with Sara Koplik, September 13, 2024.

15 Gergely, Julia, “New Yorkers with Sephardic Roots Say Spain Is Breaking Its Promise of Citizenship,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, October 14, 2021.

16 Mendoza, David, “Is Spain’s Sephardic Nationality Law Being Abused?”, The Blogs, Times of Israel, August 25, 2021.

17 Elia-Shalev, Asaf, “Sephardic Citizenship Bids at Risk Amid ‘Implosion’ of New Mexico’s Jewish Community Leadership.” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, March 30, 2022.

18 Liebman, Seymour B., New World Jewry, 1493-1825: Requiem for the Forgotten (Brooklyn, New York: KTAV Publishing House, 1982), pp. 32, 33, 42-45; Mecham, J. Lloyd, review of La Familia Carvajal by Alfonso del Toro in the Hispanic American Historical Review, November 1946 (4): 510-513; Cohen, Martin A., “Carvajal,” Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed., vol. 4, Macmillan Reference USA, 2007, pp. 501-502.

19 The organization folded in the fall of 2022, apparently for mismanagement reasons unrelated to the program for certification of Sephardic ancestry. Elia-Shalev, Asaf, “New Mexico’s Cash-Strapped, Lawsuit-Plagued Jewish Federation Announces Closure,” Jerusalem Post/JTA, November 5, 2022.

20 Casey, Nicholas, “Spain Promised Citizenship to Sephardic Jews; Now They Feel Betrayed,” New York Times, July 24, 2021.

21 Centro Cultural Sefarad (eSefarad) video on Youtube entitled, “Raíces de Sefarad: Reapertura de la Plataforma para Solicitar Certificado Sefardí con Luis Portero,” November 14, 2024. Requirements for certification by the Federación de Comunidades de Judíos de España, last viewed on December 7, 2024.

22 As noted, Casey of the New York Times reported in 2021 that, according to Spain’s justice ministry, 17,000 people who got their applications in before the deadline had been left in limbo. A statistic from the justice ministry that attorney Luis Portero displayed in the “Raíces de Sefarad” video, op cit., signifies a large improvement, or what would appear to be one, since 2021. In the Pendientes category, as of September 30, 2024: 9,263 applications.

23 See the Frequently Asked Questions page at the website of the Federación de Comunidades de Judíos de España.

24 Press release of the Comunidade Israelita do Porto (CIP), January 23, 2023.

25 Roth, Cecil, and Yom Tov Assis, “Barros Basto, Arturo Carlos de.” Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed., vol. 3, Macmillan Reference USA, 2007, pp. 177-178.

26 Quoting from a legal brief submitted to the European Public Prosecutor’s Office by the Comunidade Israelita do Porto/Comunidade Judaica do Porto (CIP/CJP), August 22, 2022: When an application came to CIP, “the first step was to decide in accordance with Halachah—the only consensual criterion in the Jewish world—as to who is Jewish or at least a son / daughter of a Jewish father.” http://firstmajorconspiracy.com.

27 The Sephardic Genealogical Society looks forward to a DNA-testing future in which archival evidence, replete with antique records that have to be tracked down and laboriously translated and interpreted, will loom less large. The technology is still in its infancy and the DNA record so far is only sparsely filled in for the Sephardim. Even when the technology improves and more people undergo DNA tests, “we think that, although you have the DNA evidence, you might still want to have the documentary tree to make it all add up,” said the Society’s vice president, Ton Tielen. “Ashkenazim with Sephardic Ancestry?” video, November 14, 2021, op cit. Tielen’s words are at the 57:00 mark.

28 Sephardic Genealogical Society, “Statement by the Sephardic Genealogical Society on the Certification of Sephardic Origin of Mr Roman Abramovich by the Jewish Community of Porto, 14 March 2022”.

29 Curado, Paulo, “Comunidade Israelita do Porto Tem Lucros Milionários com Nacionalidade Portuguesa,” Público, February 11, 2022.

30 Donn, Natasha, “Portugal’s Sephardic Jew ‘Amnesty’ Generates Tens of Millions of Euros for Israeli Community of Porto,” Portugal Resident, February 13, 2022.

31 See the commemorative volume that was published in 2023 by the Comunidade Israelita do Porto/Comunidade Judaica do Porto (CIP/CJP), Two Millennia of the Jewish Community of Oporto: Chronology 1923-2023, p. 36.

32 Shukla, Sebastian, Alex Marquardt, and Tim Lister, “Russian Oligarch Went to Moscow in Effort to Broker Complex Prisoner Exchange that Included Navalny, Sources Say”, CNN, March 9, 2024.

33 Leiderfarb, Luciana and Micael Pereira, “Putin’s Portuguese: Who Are the Powerful Ones that the Rabbi of Porto Has Approved and the Institute of Registries and Notary Has Naturalized?”, Expresso, October 26, 2023.

34 Marx, Willem, “Inside Roman Abramovich’s Quest for Portuguese Citizenship—An All-Access Pass to the EU,” Vanity Fair, May 16, 2023.

35 Sephardic Genealogy Society statement, “Changes to the Rules on Portuguese Nationality for Sephardim,” March 25, 2022.

36 Marx, “Inside Roman Abramovich’s Quest for Portuguese Citizenship,” op cit.

37 Jones, Sam, and Beatriz Ramalho da Silva, “Portugal to Change Law Under Which Roman Abramovich Gained Citizenship,” The Guardian, March 16, 2022.

38 Simyoni, Roi, “Roman Abramovich Became a Portuguese Citizen Within Half a Year; Authorities Want to Know How,” Haaretz, March 15, 2022.

39 Jones and Ramalho da Silva, “Portugal to Change Law Under Which Roman Abramovich Gained Citizenship,” op cit.

40 “Interview with the Chief Rabbi of the Jewish Community of Oporto, Rabbi Daniel Litvak,” Jornal de Noticias, reprinted in Portuguese Jewish News, January 20, 2022.

41 Sephardic Genealogical Society video on Youtube entitled, “Portuguese Nationality for Sephardic Descendants—An Update,” March 3, 2024. The video is an hour and 55 minutes long. Quoting the words of historian Teresa Santos, formerly a member of the staff of the Comunidade Israelita de Lisboa (CIL), which appear at the 1:42:30 mark.

42 “Ashkenazim with Sephardic Ancestry?” video, November 14, 2021, op cit. Schoenberg’s words begin at the 27:30 mark.

43 The dossier is available online in Portable Document Format: Roman-Abramovichs-Sephardic-origins.pdf. Legal brief submitted by CIP/CJP to the European Public Prosecutor’s Office, op cit. https://firstmajorconspiracy.com/. Moreover, it was reported in 2023 that CIP sued the Portuguese government for €10 million. Li Bartov, Shira, “The New Jews of Porto,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, December 19, 2023.

44 Sephardic Genealogical Society statement, “Changes to the Rules on Portuguese Nationality for Sephardim,” op cit.

45 Lisbona, Cuánto os Hemos Echado de Menos, p. 98. Beker (1918-1994), born in Istanbul and of Sephardic background, was a chemical engineer who made his fortune in the phosphate industry in the United States. Confessionally a Lutheran, he acquired Spanish citizenship in 1989, the same year he established a charitable organization in Madrid, the Fundación Erol Beker. José Antonio Lisbona takes note of “a suspicious balancing act” by which Beker was naturalized in the same session of the Spanish government’s Council of Ministers as was the president of the Arab Banking Corporation, Abdulla Ammar Al Saudi. Cuánto os Hemos Echado de Menos, p. 99.

46 “Portuguese Nationality for Sephardic Descendants—An Update” video, from March 3, 2024, op cit.

47 “For allegedly having intervened” is from Portugal News; “Patrick Drahi is the number two defendant in the Abramovich naturalization trial that has already led to the arrest of the Porto Rabbi,” is from an Expresso.pt post on Facebook dated March 12, 2022.

48 Teixeira, Clara and Cesaltina Pinto, “O Lado Oculto de Drahi,” Visão, July 20, 2017.

49 “Comunidade Israelita Coloca Processo de Naturalização de Patrick Drahi à Disposição da PJ,” Lusa News Agency, March 14, 2022.

50 Mendoza, “Is Spain’s Sephardic Nationality Law Being Abused?”, op cit. “It is likely that applicants who are Sephardic in the Israeli sense of ‘not Ashkenazi’ but are not of Iberian ancestry have received citizenship.”

51 Kav, Yariv, “The Trend of Israelis Applying for Portuguese Nationality,” The Portugal News, August 24, 2023. Wrote Kav: “With over 60,000 Israelis holding Portuguese nationality as of 2022, only 569 Israeli citizens reside in Portugal (per the 2022 SEF report). As a comparison, the same report indicates that 239,744 Brazilians live in Portugal.” SEF is the Portuguese Immigration and Border Service. Regarding the statistic that Kav cites for Brazilians: It counts all Brazilians living in Portugal, of whom an unspecified subset would be Sephardic Jews or descendants thereof. High Brazilian immigrant representation in Portugal is logical, given the linguistic and cultural relationship between the two nations. In like manner, when it comes to individuals seeking Spanish citizenship under Spain’s 2015 Sephardic law, the largest national contingents of applicants are from the Spanish-speaking countries of Latin America.

52 Israel is not unique in this respect; Russia is another country with its own list of countries that have banned the entry of its citizens, especially after it invaded Ukraine.

53 Danielle Avidago, Unlocking Heritage: The Evolution of the Portuguese Citizenship Application for Descendants of Portuguese Sephardic Jews. LVP Advogados, September 23, 2024.

54 “Portuguese Nationality for Sephardic Descendants—An Update” video, March 3, 2024, op cit. Santos, the former CIL staffer, makes this observation at the 51 minute mark.