Spain’s correction of her “Historical Mistake and Injustice”: Spanish citizenship for the ‘sefardies’: An assessment

by Doğan Akman[1]

“No kale espalder los piezes mas ke la kolça”[2]

Sephardic proverb

“The past is never dead. It is not even past.”

William Faulkner

A. Introduction

La Ley 12/2015 en materia de concesión de la nacionalidad Española a los sefardies originarios de España enacted on June 11, 2015, received Royal Assent on June 24 and came into force and effect on October 1, 2015 (the “law “, “ legislation” “legislative scheme”).[3]

The objects of this paper are twofold; first, to set out the key provisions of the legislation read in tandem with the Instructions[4] issued on September 29, 2015(“Instructions”) by the General Directorate of the Registries and Notaries (“DGRN”)[5] and, second, to identify and analyze the significant issues raised by a fair number of these provisions and by the legislation as a whole.[6]

Clearly, the legislation does not stand on its own provisions as these are not exhaustive of all the matters affecting the acquisition of nationality. In some instances, in order to obtain a better understanding of the legislative scheme, some of its provisions need to be read and interpreted in conjunction with those of other legislation. Due to the constraints of space, this paper focuses primarily on the provisions of the legislation that stand on their own, save where the rationale for one particular provision are meant to be read together with some of the Spanish Constitution.[7]

B. Legislative Objectives

I. The government’s publicly stated objectives

According to the government, the objectives of the legislation are four-fold:

First, to admit that Spain made a “historical mistake” by “unjustly” expelling the ancestors of a sub-group of what is now commonly referred to the Sephardic Diaspora (“Diaspora”), who resided on the Spanish Iberian Peninsula (“Sefardies”) and were expelled pursuant to the Alhambra Decree of March 30, 1492 (“Edict of Expulsion”, “Edict”) upon their refusal to convert to Catholicism.

Second, to repair, to make amends for and to correct this historical mistake and injustice.

Third, to state what the government expects to achieve with this legislation. These expectations are set out in the concluding paragraph of the Preamble which reads: "In final analysis, this law is expected [a] to be the meeting point of today's Spaniards with the descendants of those that were unjustly expelled in 1492; [b] to prove the common determination to build together a new space of co-existence and harmony against the intolerance of the past ages, and [c] through this common determination, to re-open forever for the communities expelled from Spain, the doors of their ancient country.”[8]

Fourth, to provide the means by which these expectations will be met; namely (a) to make “restitution” to those among the descendants (the “applicant(s)”) who are able to satisfy both the evidentiary and procedural requirements set out in the law, by establishing their entitlement to citizenship as a matter of right (as opposed to being subject to governmental discretion); (b) to broaden the descendants’ opportunities for acquiring the Spanish citizenship by repealing the prohibition against possession of dual nationality, and (c)to expedite the time frame within which their applications will be processed by prescribing legislative deadlines.

Laudable as these sentiments and objectives may appear, to call the abomination of the expulsions and the abominable conditions under which the expulsion occurred a mere “mistake” and a generic “injustice” exhibits neither a genuine appreciation of the true depths and scope of the inhumanity perpetrated by the two Spanish Crowns on the expelled Sephardic Jews nor a genuine empathy for their fate.

As a matter of fact, after reviewing the wording of the Preamble, the various pronouncements of Ministers and other dignitaries, one cannot help but tend to agree with the witty suggestion that under this legislative scheme the descendants are being rewarded more for preserving their Ladino, for their ancestor’s enduring love for Spain, and for disseminating Spanish language and culture than to correct the historical mistake cum injustice.[9]

The government’s failure to seize this perfect opportunity to apologize for coercing Jews to convert in order to remain in Spain and for the abominations perpetrated against the converted Jews by the Spanish Inquisition operating under Royal authority lends further credence to the feeling that the thoughts and sentiments expressed in the Preamble are more in the realm of poetic diplomacy than in that of genuine earthly regret, apology and equitable restitution.

Finally, I use the term “sub-group” of the Spanish Sephardic Diaspora because as a matter of historical record, between 1348 and 1945, Spain caused not one but nine Diasporas.[10]

A curious exclusion-The expulsion of Jews from Navarra

In 1492 the territory of the Kingdom of Navarra (“Navarre”) south of the Pyrenees was located on the Iberian Peninsula. In 1512, this territory was conquered by the Castilian-Aragonese army and annexed to Castile. It has since become one of the autonomous communities of Spain. The King of Navarre, under the insistent pressure of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain finally agreed to and in 1498 expelled the Jewish inhabitants of his Kingdom who refused to convert. By so doing he fulfilled the dream of the Catholic Monarchs to render the Spanish Iberian Peninsula Judenrein.

In fact, had the King had not done it, the Catholic Monarchs would have carried out the expulsion upon their conquest in order to preserve their ideal of maintaining the Spanish Iberian Peninsula in Catholic religious purity.

On these evidentiary premises, it is rather curious, indeed incomprehensible, that the Spanish government elected to keep the Sephardic Jews of Navarre out of the purview of the new legislation, particularly since the Catholic Monarchs were very much a party to the decision to expel. Besides, surely, through the conquest the Spanish Crowns assumed not only the legal rights of the former Kingdom but also its moral liabilities including that resulting for the same kind of injustice perpetrated in 1492 which the government now seeks to repair.

II. Two key unstated critical objectives of the legislation

These objectives are: first, to secure Sephardic commercial and industrial entrepreneurial expertise and capital investment,[11] that the government hopes will contribute to the re-invigoration of the Spanish economy on a sustained basis, and second, to improve Spanish society’s sagging international image for its views on and treatment of its ethnic and religious minorities.

1. First objective: To secure Sephardic commercial and industrial entrepreneurial expertise and capital investment.

(a) Historical perspective: Sefarditismo económico de las derechas and filosefardismo político

The legislative scheme of 2015 and the one it replaced are neither new nor original. Historically, Spain has been interested in attracting successful Sephardic entrepreneurs as far back as 1797 and successful Sephardic Ottoman entrepreneurs from 1881 onwards. This interest has been based on the Spanish economic policy to align the capital, entrepreneurship skills and successes of these entrepreneurs with the economic interests of Spain, and, if possible, to induce them to return to Spain and inject much needed economic stimuli to its moribund economy. Sagnier, borrowing the title of a news report published in 1930, describes this policy as Sefarditismo económico.[12]

Pedro Valera and later Primo de Rivera appropriated the concept and developed their own version subsumed under the rubric of Sefarditismo económico de las derechas.

In 1797, Valera, a man well ahead of his time in economic and financial matters, saw the potential benefits that could be secured from attracting rich Jews to settle in Spain. With the support of King Carlos III, he proposed to abolish the Edict of Expulsion and developed a plan to do that.[13] He failed to secure the support of the ruling class that seems to have been still wedded to the Edict of Expulsion, the doctrine of limpieza de sangre (purity of blood),[14] in an era when the mind-set generated by the Inquisition still lay claim to the thinking of this class.

Following on the footsteps of Valero, Primo de Rivera did not manage to do better with his 1924 Decree.[15]

The Decree was designed to pursue the economic policy of Valera in order to entice Ottoman Sephardic entrepreneurs to move back to Spain by affording them a further opportunity to secure Spanish consular protection and Spanish citizenship. The scheme did not produce the desired results, in part, due to the failure (a) to advertise and promote the Decree widely throughout the Empire instead of confining its diffusion to a limited number of districts, and (b) to attract sufficient interest in the merchant class targeted by the scheme. The scheme also failed because, save for rare possible exceptions, the merchants in question showed no interest in moving to Spain and instead focused on taking whatever benefits they could derive from the Decree.

While in those days, an explicit official admission of wrongdoing for the issuance of the Edict of Expulsion was unthinkable, and this remained so well after the re-establishment of the Monarchy in 1975, the gentle and caring tone of the pertinent excerpt of the Preamble of Rivera’s Decree goes some ways in that direction. It addressed the Sefardies as follows:” Ancient protected Spaniards and their descendants, and in general individuals belonging to families of Spanish origin who on some occasion were inscribed in Spanish Registers, and these Hispanic persons with deep sentiments of love for Spain who by reason of ignorance of the law or for whatever other reason foreign to their will to be Spanish, have not been able to attain our citizenship.”[16] (Italics mine)

General Franco in turn pursued the Sefarditismo económico de la derecha by combining it with Sefarditismo político and in some ways with filosefardismo, in so far as his public utterances and actions in keeping with these concepts would be tolerable to the deeply ingrained anti-Semitism of the fascist elite and of the Church. Franco`s exchange of notes with Greece (1935) and Egypt (1936) concerning the Sefardies in these countries to whom the government afforded consular protection must be also considered in the context of picking up the remaining pieces in the aftermath of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of Turkey in 1923.On the other hand, Franco considered the Decree of 29 December 1948 as an act of generosity which he hoped might help develop Spain’s disaffected relations with the newly established State of Israel.[17]

In the event one of the key objectives of the government underlying the legislation is indeed to re-introduce historical Sefarditismo económico to Spain, it is reasonable to expect that the government would set out to entice applicants who are mostly actual and potential members of entrepreneurial, industrial, financial class of applicants.

As noted further below, an indication of this intention can also be inferred from the fact that the existence of a commercial relationship with or business interests in Spain as well as ownership of property are considered to be indicia of (special) personal connections to Spain.

(b) Historical perspective: Sefarditismo económico de las derechas, filosefardismo de las derechas and filosefardismo

Ironically, the Sefarditismo económico de las derechas of generals Rivera and Franco also had a component of an implied filosefardismo de las derechas. Consequently, their right-wing economic pursuits with the Sefardies gained widespread support among the liberal political and intellectual elites because it converged with their filosefardismo movement[18] which emerged and blossomed between the last quarter of the 19th century and the Spanish civil war. The movement was revived after the civil war and gained further strength and upon the re-establishment of the Constitutional Monarchy. The movement championed the return of the Sefardies from the Diaspora on the belief that they would immeasurably enrich Spanish society, well beyond the spheres of economics and finance. Towards this end, the movement sought to have the government make amends for the Edict by repealing it.[19]

Filosefardismo focused on the Ottoman Sephardic Jews first germinated after Spain and the Ottoman Empire made permanent peace, established diplomatic relations and, early in the 19th century, Spanish diplomats, reporters, writers and travellers (sometimes one person performing all four roles) began to arrive in the Empire and suddenly encountered the descendants of the Sefardies who were expelled in 1492 or fled from the Iberian Peninsula between the 14th and the 18th centuries.

The diplomats and visitors were much surprised to hear the Sefardies speak Castilian Spanish (of a kind), express no hostility towards Spain for the expulsion of their forebears and instead express their love of and nostalgia for Spain. The Spaniards were further surprised that the Sefardies maintained their historical, cultural and religious practices, despite the passage of centuries.

These revelations of these encounters with the Ottoman Sefardies, unlike the details of the earlier encounter between the Spanish soldiers and the Moroccan Sephardic Jews that mostly did not make it past military reports, generated news reports, travel books and novels in Spain.

Knowing my people as I think I do, it is not unreasonable to suggest that the absence of hostility to and the expressions of love and nostalgia for Spain were in good measure self-induced; triggered, as they were by the problems of living in an Empire in severe distress, on the downward spiral, and their preoccupation with the fact that Ottoman Jewry, unlike Ottoman Christians, enjoyed none of the privileges of consular protection provided and citizenship granted to the latter by their patrons, the European powers. Consequently, the Sefardies were anxious to secure the same privileges from Spain. This they managed to do so thanks to the combined effect of sefarditismo económico and filosefardismo.

So it was that between 1809 and 1913, the Spanish government was the only Western government to provide, as a matter of policy, some of the Ottoman Sefardies with practical assistance, some with consular protection and a lesser number with citizenship.

This continued from the end of World War I to the Spanish Civil War; during World War II when Franco was compelled to act under the pressure of the Allies, (while at the same time playing sweet with Hitler) and on three further occasions after 1945.[20]

In effect, Sefarditismo económico de las derechas both incorporated and complemented the filosefardismo movement as the former came about when the Spaniards also discovered the entrepreneurial skills and commercial successes of the Ottoman Sephardic merchants and decided to make something of them for the benefit of Spain.[21]

2. The Second objective: To improve Spain`s international image with respect to the nation’s views and treatment of its ethnic and religious minorities

I submit that the government decided to move with the legislative project also in an attempt to address a pressing problem: namely, the need to improve Spain’s international image with respect to the nation’s views and treatment of its ethnic and religious minorities.[22]

I further submit that the second key unstated objective of this legislation is to engage in an international public relations exercise to counter the irrefutable facts confirmed by numerous authoritative surveys supplemented by a substantial body of writing[23] that xenophobia in Spain manifested by hostility to minorities, immigrants, the Roma, and anti-Semitism/Judeophobia in particular, are alive, well and thriving. It is expressed in the printed press including the large-circulation papers, in the electronic media, in public broadcasting, in public attitudes, behaviour and discourse. The expressions and discourse include the continued use of some traditional anti-Semitic expressions; popular participation in events that have anti-Semitic origins such as, for example, the continuing celebration of the commemorative Mass of the child saint of La Guardia who was the fictitious victim of a fictitious blood libel.

The existence and the continuing nature of the problem of anti-Semitism are also touched upon in the concluding paragraph of the Preamble and demonstrated by ample evidence.

In fairness to Spain, the government has so far taken two steps in a modest beginning to address anti-Semitism. The first one is in the nature of a deterrent based on the March 31, 2015 amendment of Articles 510 and 607 of the Spanish Criminal Code in order to provide a powerful tool for the prosecution of speeches of anti-Semitic hatred and other discriminatory motives.[24] The effectiveness of this initiative remains to be seen as these types of cases are not easy to prosecute and the Courts are loath to abrogate the freedom of speech--one of the fundamental features of western democratic societies where the freedom is protected under the Constitution or by other legislative enactments, as the case may be. At all events, it has been pointed out below, and experience shows, that this type of legislation cannot resolve the problems of ethnic, racial or religious stereotyping and hatred without a significant investment in educational tools designed to address and hopefully to counteract this type of hatred to some measure.

On the educational front, the Spanish Parliament has voted to make Holocaust awareness education mandatory in schools.

The extent to which the government and Parliament are prepared to build up and expand on these initial steps remains to be seen. In the meantime, anti-Semitic manifestations carry on.

At all events, the last paragraph of the Preamble that addresses the object of the legislation and the expectations that accompany it were cut short by the then Minister of Justice Albert Ruiz Gallardón who, on the occasion of the Cabinet’s approval of the first Bill of February 7, 2014, explained the decision to proceed with the Bill in terms of its “reflect[ing] the reality of Spanish society as an open, plural society where one’s identity is defined by the recognition of diversity.” Presumably to reinforce his point, the Minister further stated that, under [Article 1 of] the Bill, citizenship would be granted regardless of the ideology, religion or the beliefs of the applicants.[25] Assuming that the Minister has not misspoken, I very much fear that the provisos of “freedom of ideology and of belief” are potentially liable to make a cruel joke or two of all the solemn promises and pronouncements that preceded the Bill and are re-stated in some fashion in the Preambles of both Bills and of the legislation.

Curiously enough, for reasons which to the best of my knowledge have not been stated publicly, the proviso in Article 1 was omitted from the Bill of June 24, 2014 and does not appear in the legislation.

Gallardón's successor Rafael Catalá, carried on with the denial of the true state of affairs concerning xenophobia and in particular, anti-Semitism in Spain. Upon the enactment of the legislation he declared: “This law says a lot of about what we were in the past, what we are today and what we want to continue to be in the future--an open, diverse and tolerant society.”[26] (Italics mine) Later, during a visit to Jerusalem to promote the legislation and its virtues, Catalá further declared that the legislation “made Spain a better society.”[27]

The Spanish Ambassador to Israel, among others, characterized the legislation as “an act of reparation of an injustice” and “the recognition of the work of the ancestors of the Sefardies in Spain and of all their contributions to the Spanish culture during many centuries, as much to its history as to its culture and to the government of Spain;[and] of the value of having maintained the special link and the steadfastness during more than 500 years, despite the weight of having been expelled unjustly.”[28]

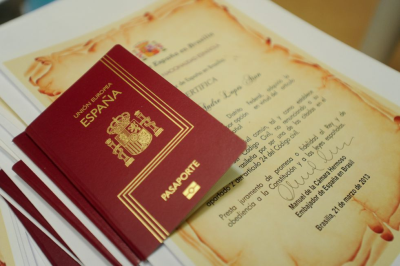

III. Advertising: The stage-managed launching of the new law

The legislation came into force on October 1,2015, together with the government`s stage-managed decision bearing the same date to approve the citizenship applications of no less than 4302 Sephardic Jews, whose applications had been in the works for up to ten years-- from 2005 to October 1, 2015.[29]

C. Statutory Provisions Governing the Access of the Sefardies to Citizenship Prior to October 1, 2015: The Two Routes to Citizenship

As the law stood prior to October 1, 2015, the descendants applied for Spanish citizenship by one of the following two routes, namely; by way of naturalization (carta de naturaleza) or a minimum of two years of residence in the country immediately prior to filing an application for citizenship, each route prescribing its own distinct set of evidentiary requirements. In this paper, I focus on the first route.

I. Obtaining citizenship by naturalization by Royal Decree –Article 21.1 of the Código Civil (Civil Code)[30]

1. The basic scheme

Prior to the new law, the Spanish Council of Ministers (“Cabinet”) operated on the basis that applicants who were able to prove that they possessed a “Spanish Sephardic identity” and a “ special personal connection to Spain “ (“personal connection”) established the existence of “exceptional circumstances” which entitled them to apply for citizenship by way of naturalization by Royal Decree under the provisions of Article 21.1 of the Código Civil (Civil Code).

In the ordinary course of events, the expectation was that the Cabinet would exercise its discretion in favor of the applicant who established the existence of “exceptional circumstances,” and recommend to the King that the applicant be granted the citizenship. The King did so by issuing a Royal Decree to that effect.

2. Proof of “exceptional circumstances”

In practice, the exceptional circumstances were usually established by the Certificate issued by the Federación de Communidades Judias de España (Federation of Jewish Communities of Spain “FCJE”)[31] signed by its authorized officer, attesting to the facts that the applicant is Jewish; of Spanish Sephardic cultural and, where possible, linguistic tradition (Ladino or Haketia) or in other words, that the applicant possessed the requisite combination of Sephardic identity and personal connection to Spain. In some instances, the applicant proceeded without obtaining the Certificate and instead filed both their applications and their entire evidence with the Cabinet.

The concept of “exceptional circumstances” is now embodied in Article 1.1 of the new law .However, as it will be shown below, the burden of the evidentiary requirements to establish these circumstances under the new legislation are more burdensome than they had been prior to the legislation.

3. Supplementary evidence

In addition to the evidence of “exceptional circumstances”, the applicant was also required to submit personal information about all members of the family and related supporting documents like birth, marriage, citizenship certificates, certificates related to criminal records and others. This proof continues to be required under the legislation.

II. The problems associated with the criteria and application of the law governing the acquisition of citizenship by naturalization by Sefardies prior to October 1, 2015

1. The major impediments

The four major impediments to the acquisition of Spanish citizenship by way of naturalization were:(1) the government’s unfettered discretion to entertain such applications in the first instance, let alone to accept or reject them. As the Zapatero incident illustrates,[34] the government of the day was able to decline to entertain the applications for reasons that are wholly immaterial to the merits of the applications; (2) with the exception of Sefardies who are nationals of a country included in the group of countries identified above, those who acquired the citizenship were required to renounce all the other citizenships they held; (3) the excessively long duration of the process, and (4) the considerable cost of prosecuting the applications, without any certainty that the application would succeed.

To these, I am inclined to hypothesize a fifth one; namely, the lack of transparency in the decision-making process, as the applicants were kept in the dark as to the specific facts and circumstances upon which the Cabinet relied in reaching its decision, particularly when the application was rejected.

Historically, the impediments (2) to (4) inclusive and the applicants’ indifference to or the lack of interest in settling in Spain probably accounted for the relatively modest response of the Sephardic Diaspora to the former naturalization process.

On the whole, the applicants preferred the naturalization process over the one that required residence.

2. The provisions new legislation related to the impediments

The new legislation (a) removes impediments (1) and (2); (b) appears to mitigate somewhat impediment (3) through the establishment of certain time limits in the decision-making process, but (c) neglects to address, and possibly compounds impediment (4).

With respect to the third impediment, the legislation may in fact compound the problem for an indeterminable proportion of the applicants by causing the lengthening of the extra time they may need (a) to assemble the evidence and/or, b) the extra time that they will need to pass minimally one examination and, for an as yet indeterminate number of them, to pass a second one, i.e. the language examination.

Insofar as the suggested fifth impediment is concerned, for reasons outlined below, the legislation compounds the lack of transparency.

III. The promise of 2012 and the legislative initiatives of February 24, and June 6, 2014 to enhance the access of the Sefardies to Spanish citizenship

1. The promises

On November 22, 2012, at a ceremony held at Madrid’s Casa Sefarad-Israel, the then Justice Minister Alberto Ruiz Gallardón accompanied by the Minister of External Affairs and Co-operation, solemnly announced that the Spanish government would offer to Spanish Sefardies whose ancestors were expelled from Spain in 1492 who could prove their Sephardic identity and their personal connection to Spain[35] an improved scheme of citizenship by naturalization; outlined the new approach and some of the proposed improvements.

The promises were warmly received both by the FCJE [36] and by the Sephardic Diaspora. It did not take long for some to dub the project, albeit prematurely, and as it turned out, incorrectly, as the “Spanish Law of Return” by analogy to the Israeli law, commonly referred to as the “Law of Return.”

Regrettably, the promises were slow to be written up as legislative provisions, which did not happen until 2014.[37]

2. The Bill approved by the Cabinet on February 7, 2014 [38]

On February 7, 2014 the Cabinet received and approved the Bill (draft legislation) setting out provisions that embodied the promises of reform.

Again, the Bill was also warmly received by the FCJE and caused a great deal of excitement in the Diaspora, one which a reporter described as “frenzy.” [39]

However, judging from the fate of the Bill and the subsequent conduct of the government, it is reasonable to suggest that Cabinet approved the Bill merely to gain time and had no intention whatsoever to proceed with it.. Although, two months later, the government announced the establishment of “objective criteria” for the implementation of the Bill, it was a stillborn endeavour. The Bill, compared to that which was to follow and to the resulting legislation, was too good to be true.

More specifically, it consisted of a mere three pages with one and half spaced type-written lines comprising merely two Articles, the first of which addressed all the evidentiary matters, while the second dealt with the procedural ones, and a few minor additional provisos. The Bill held out the promises that the evidentiary requirements will not be more onerous than they had been, while the procedure will be reasonable, accommodating and applicant friendly, among other things, in terms of costs. Ironically enough, the Bill also opened the path to citizenship for the descendants of those who at one point in time subsequent to their expulsion, voluntarily or otherwise, converted to Christianity, or for that matter to Islam, as has been the case in the Ottoman Empire , and for the descendants who are present-day crypto-Jews.[40]

Nevertheless, the Bill discriminated, and the new law presumably continues to do so, albeit without the clause, in favour of these three classes of applicants and against the descendants of the Sefardies who in 1492 chose to convert in order to remain in Spain and Navarra and of those who had converted but, faced with the horrors of the Inquisition, fled the country.

Of course, whether and how these non-Jewish descendants will manage to prove their “Sephardic identity” as defined in the legislation remains to be seen. Save for crypto-Jews, and even then, in the historical background and context of the legislation, it is difficult (but not impossible) to conceive of the life histories of Christian or Muslim Sefardies and even of crypto–Jews that are likely to satisfy the statutory requirements and criteria of eligibility under the new legislation.

3. From the Bill of June 6, 2014 to the Law of June 21, 2015

On June 6, 2014, the Cabinet was presented with and approved a second Bill. [41] The new Bill was nine pages long, almost 30% longer than the previous Bill, bore little resemblance to the former one both in terms of the relative simplicity of the evidentiary requirements and of the procedural provisions. The new Bill also increased the application fee to 100 Euros.

The new Bill did not have smooth sailing and the legislative process experienced a number of delays and difficulties. From June 10, 2014 when it was first presented to the Spanish Parliament, it took until June 24, 2015 to receive Royal Assent and become law.

At one point, the delays of the government in addressing what it considered to be complications became such that, in order to expedite the passage of the legislation, representatives of both FCJE and the Sephardic Diaspora urged the government, to no avail, to adopt the framework of the corresponding Portuguese legislation enacted earlier that year, despite the fact that the Portuguese legislation includes the proviso that the Cabinet retains the unfettered discretion to reject an application.

It is fair to say that the legislation fails to keep faith with the generous spirit which the government sought to convey earlier.

It is also fair to say that despite the improvements noted above with respect to the pre-existing impediments, the new scheme remains a complex one which is not applicantfriendly.

The proposed legislation was the subject of passionate debate and criticism in Parliament, where it was described as; (a) window dressing; (b) a political, symbolic or an empty gesture rather than an effective one;(c) insensitive towards the old; (d) a jumble of provisions, irrelevancies and democratic outrages; (e) a series of unjustifiably onerous and difficult hurdles; (f) lacking generosity and nimbleness, and (h) financially onerous and discriminatory to the poor. There was also vociferous objection to the increase of the application fee to 100 Euros.[42] Even making allowances for political partisanship, on the whole, these criticisms are substantiated in good measure on the grounds set out below.

a. Reception of the Bill of June 6, 2014 by the FCJE

The Bill somewhat dampened the original enthusiasm expressed by the FCJE and various representatives of the Sephardic Diaspora.

In June 2014, despite the solid evidence to the contrary, Isaac Querub Caro,[43] President of the FCJE, categorically stated his belief (the standard one expressed by Sephardic officialdom in Spain) that Spain is not an anti-Semitic country and sought to explain away the existing anti-Semitism with what I consider to be a rather simplistic notion, thatthis existing anti-Semitism is caused by “ignorance and disinformation about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.” However , he then went on to qualify his categorical belief by asserting that the Church “… needs to be more proactive [in the fight against prejudices] because many of the prejudices are of religious origin. For example, it would please me if [the Church] would prohibit the celebration of the sainted child of La Guardia.”[44]

b. The voting on the proposed law

The enactment of the law was hyped by the fact that the vote in support of the legislation was (technically) unanimous on the basis that no one voted against it. The actual outcome can be hardly described as unanimous since the Bill passed with 292 votes in favour, 16 abstentions and 42 no-shows.[45]

c. Reception of the law by Querub and the FCJE

A year later, on June 11, 2015, upon the enactment of the law, Querub, in the presence of the Minister of Justice Rafael Catalá and José Manual Barcia Margallo, Minister of Foreign Affairs, declared that the law “opens a new era for the Jewish community... It is a day of hope and happiness.” (Italics mine). Querub after expressing his gratitude to the government, further stated that “…this is a law that arrived somewhat late but validated the idea that Spain `has arrived for its appointment with history’” and continued “I hope that this will serve to make Spain a better place with more diversity’.”[46](Italics mine) Yet, on the same date, in an op-ed published in the Spanish newspaper El Pais, he wrote: “We hope that Jewish life will be considered normal in the Spanish society, which will act as an antidote against prejudice and stereotype.”[47] (Italics mine). He expressed his satisfaction with the law and characterised it as a “moral redress,” whatever he may have meant by that phrase, and a new stage in the relation of the Jewish community with the Spanish one (Italics mine). He did, however, express regret about “the complexity of the process” through which the applicants are required to navigate with their applications.[48]

Querub said more or less what officialdom expected him to say in order to remain in the good books of the government and of the audience at large. Nevertheless, on close reading of his pronouncements, I find the words which he chose to address the legislation in the context of the past and present of the Jewish community in Spain, the perception of this community and the attitudes towards it by the dominant society, to be tentative and rather sad considering that it was 2015. Querub spoke in terms of hopes, knowing, as he must know or at least feel, that the hopes he expressed are not quite warranted by his firsthand knowledge of the contemporary socio-cultural realities of Spanish society.[49] Given his pre-eminent position in the organization of the Jewish communities of Spain, I venture to suggest that what he said and the way he said it reflect the true inner thoughts and feelings of the members of the community he serves.

The FCJE as an organization, possibly keeping in mind the old Sephardic adage “Ken kere mas, resive manko” (Ladino, “one who wants or asks for more, receives less”) demonstrated a more upbeat approach on its website with equal parts of self-congratulatory joy, and profuse expressions of gratitude to the government that reiterated the sentiments expressed in the last paragraph of the Preamble. The FCJE speculated by predicting, rather outlandishly, that: “Today begins a new stage in the history of relations between Spain and the Jewish world; a new period of meeting again, of dialogue and harmony that will fully reintegrate a branch of the Spanish nation that in its day was unjustly torn off.”[50] (Italics mine).

For the occasion, the website also quoted in bold letters the first part of the often quoted statement of former King Don Juan I who on the occasion of his praying at the Beth Yaakov synagogue in Madrid in 1992 to mark the 500th year of the Edict declared: “Sefarad is not a nostalgia but a home and it ought not be said that Jews feel at home because the Spanish Jews are in their own home.”[51]

To sum up, considering the fact that the legislation was not enacted in response to a popular clamor for it, surely there is no logical connection or, at best, there is a highly tenuous one, between the enactment of the law and the outcomes the Preamble targeted, Quorum hoped for, and FCJE predicted.

At all events, the phrases ‘new beginning’, ‘new relations’, ‘new era’, ‘new stage’ and ‘new period’ bandied about to characterize the legislation are hardly accurate. As a matter of historical record, I would have thought that the very first ‘new’ whatever occurred (1) in 1809 followed by those in (2) 1891;(3) 1924-1930; (4) 1935-1936; (5) during the first part of World War II; (6) 1948 ;(7) 1968 when the Spanish government officially rescinded the Edict of 1492 which, as a matter of fact, already had been rescinded, by the operation of law through various Constitutional and other legal enactments; and established diplomatic relations with the State of Israel; (8) 1975 and during the years following the re-establishment of the Constitutional Monarchy and the reconciliatory declarations and gestures of the former King Don Juan I, (particularly in 1992 marking the 500th year since the Edict of Expulsion and the expulsion of 1492) and in (9) 2004 with the establishment of the previous regime of naturalization.

I have no doubt that a closer look at the history of Spain and of its Sephardic community would disclose many more such new things

By my restrained accounting of historical events as ‘new’ relations, era, stage or period, the new law then is the 10th one in the last 207 years. Most regrettably, it is the one that opens the doors to the descendants of the “ancient sons of Spain” to come back home under the most onerous legislation to date.

4. Reception of the legislation in the Sephardic Diaspora and in Israel

The Sephardic Diaspora does not seem to be ready to adopt the outwardly enthusiastic posturing of its Spanish brethren. For example, the best Abraham Haim, President of the Council of Sefardies in Jerusalem, could bring himself to say was: “I am prudent and I do not like to say that this law does justice. Let us say that it improves the image of Spain a little and adds pieces to the mosaic of the re-encounter of two peoples.”[52]

Leon Amiras, President of the Israeli Organization of the Immigrants in Israel from Latin America, Spain and Portugal (OLEI) after describing the Spanish legislation as a “symbolic gesture,” analogized the difference between the Portuguese and Spanish legislative schemes: “ as being the difference between a girlfriend who loves you [Portugal] and one that hasn’t quite decided yet.”

Others, after making some muted criticism of the legislation adopted a ‘wait and see attitude’, on the premise of the old adage that ‘the proof of the pudding is in the eating’.[53]

5. Looking forward

I venture to opine that whatever enthusiasm for the law remains, it will be further dampened after the prospective or current applicants begin to gain a fuller appreciation of the legislative bureaucratic and financial hurdles they must get through. I also venture to predict that some members of each of these two classes of applicants will be less than enthusiastic, especially those who (a) have modest means; (b) are old;(c) lack sophistication in the ways of the world;(d) have limited education; (e) never appeared before a judge or a judicial officer in a legal proceeding; especially one conducted in a language in which they lack oral fluency and spoken in a way that is foreign to their ears; (f) for a variety of reasons, are not or do not feel suited to appear in person in a proceeding;(g) do not have any experience in retaining, instructing a lawyer at all or for this particular type of case which involves the laws both a domestic and a foreign jurisdiction; (h) have had no occasion to deal with legal bills; or (i) have no idea of the kind of intestinal fortitude required to go through with such a case.

IV. Preliminary Matters

1. Definition of the term “sefardies” in the legislation

The term “sefardies”, is defined in the introductory sentence of the Preamble. The applicants are bound by this definition which restricts the ancestry of the applicants to those expelled from Spain in 1492 pursuant to the Edict .The descendants whose ancestors were not part of the 1492 group are ineligible to apply. Accordingly, the current popular broad definition of the term has no bearing on this legislation.

2. The implied “sunset clause”

The Spanish legislation, as presently framed, is set to expire at an as yet undeterminable date counting from the conclusion of a period of three years, with a possible maximum of four, which commenced to run on October 1, 2015 within which the applications accompanied by the supporting documentary and other evidence must be filed. These limitation periods are subject to two specific exceptions addressed below in Part K.I

These deadlines raise the question as to whether this legislation is a one-time final offer or a period of time waiting to be followed by another new stage, era, period and the like, pending the intentions of the government of the day when the legislation will be due to expire or expires.

Actually, , the legislation has another built-in expiry date because the pool of applicants who can handle or prove some of the evidentiary requirements concerning Sephardic identity and personal link, will shrink at an accelerated rate, starting with the youngest generation of applicants and their successor generations.

3. Children of mixed marriages

I am unable to address this issue both due to constraints of space as well as due to my lack of familiarity with the issues raised by such marriages or series of marriages in the context of establishing Sephardic identity.

4. Age and disability factors in determining the eligibility to apply

The legislation sets the minimum age of eligibility to apply for citizenship at 18. Beyond that, the question of the entitlements of: adults with various types of civil and/or medical disabilities; the wholly incapacitated; the non-emancipated; minors under 18 and in particular those of 14 and under, raise complex legal issues of private international law governed by juridical regime of the country where these potential applicants normally reside, read in conjunction with the Spanish domestic law.[54]

Due to constraints of space, this paper focuses solely on applicants who enjoy the right to apply.

D. The Fundamental Evidentiary Criteria to Establish Entitlement to Citizenship

There are three fundamental criteria which the applicants must meet in order to establish their right to acquire citizenship; first, to be a descendant of the Jews expelled from the Spanish Iberian Peninsula in 1492; second , to possess a Sephardic identity, and third, to have a personal connection to Spain.

E. Evidentiary Requirements (1): Proof of Sephardic Identity by Certification

I. “Certificate of Sephardic Identity”- Three types of certificates- Article 1.2(a) to (c) inclusive[55]

The President of the Permanent Commission of the FCJE is authorized to issue a certificate of Sephardic Identity upon the applicant’s submission of the documentary evidence prescribed by the legislation. The Commission operates at arm’s length from the government.

The FCJE has given a public undertaking to respond to each application for a Certificate within three months from the date of the application.

The Certificate may also be issued, by any Jewish community, regardless whether it is a Sephardic one or not. Based on my experience and observations, generally speaking Ashkenazi rabbis and community leaders in Canada (and possibly in some parts of the United States) are not particularly knowledgeable about Sephardic history, culture, traditions and practices, let alone the idioms.

Hence, this legislative criteria unfairly discriminates against applicants (a) who are not properly speaking, members of an existing organized Sephardic community and congregation; (b) were born or reside in an area which does not have such a community and congregation; (c) live in a country (i) with a tiny or small Sephardic population dispersed across the country and particularly across a large one like Canada; or (ii) where organized Sephardic communities or congregations or (iii) both; and (iv) if they exist, are not located within a reasonable distance of the applicants’ residence or workplace;(d) who do not attend a Sephardic or any other synagogue for a variety of reasons best known to themselves and are otherwise not known to the community ; (e) who are in an equally difficult situation in their native city from which they emigrated a long time ago as an infant or a young child; whose parents were not born or married there and did not live there long enough and passed away elsewhere, or (f) at all events, who cannot access their place of birth. Such scenarios can hardly be said to be far-fetched in the light of (a) the rapid secularization of the Sephardic Diaspora or, (b) their assimilation into the Ashkenazi communities, and (c) the Jewish Diaspora’s historically high rates of geographical mobility, forced or voluntary.

In the result, this class of applicants would have a rather hard time securing any of the three certificates prescribed by law, namely those issued by (a) the FCJE under Article 1.2(a); (b) the community of the applicant in the way prescribed manner in Article 1.2(b) or (c) by the rabbinate under Article 1.2(c) with the supplementary requirements related to the institutions of the second and third.

This discrimination is compounded in the event the FCJE is not prepared or is unable to issue its own certificate of Sephardic identity where the documentary evidence submitted by such an applicant are not adequate or raise factual and historical issues which the applicant is either unable to address to the satisfaction of the FCJE or as it turns out, addresses them in a manner detrimental to the application.

The FCJE Certificate carries great weight because of (a) the historical and statutory relationship between the organization and the Spanish state;(b) the organization’s longstanding and well-established relations with and knowledge of the Sephardic Diaspora;(c) its substantial and in many ways unique experience in (i) assessing the probative value of the evidence tendered by the applicant, and (ii) determining whether the Certificate ought to be issued or declined. [56]

Of greater interest to the applicants, it is possible to insert in the Certificate a number of facts supporting other requirements or criteria, thereby dispensing with the need to secure the evidence of those facts separately at some cost both in time and money.

On the whole, the Certificate dispenses with a great deal of additional tedious and, at times, frustrating work which the applicant would have to do in the absence of a Certificate, and again, in the process, it saves both additional time and money.

For its services related to the certification process, the FCJE charges the princely fee of 60.50 Euros (including the 21% VAT) payable after the Certificate is issued. [57]

The FCJE’s website provides some very useful information about the citizenship process and the applications to obtain one of its certificates and a very limited amount of summary statistics. [58] Nevertheless, the organization’s information package is deficient in that it fails to provide the potential and actual applicants with other kinds of information that would greatly assist them in addressing their concerns about the legislative process. For example, the FCJE does not publish (a) the number and percentage of applicants who fail to obtain the Certificate; informative statistics about the operation of the Certificate system; (b) a description of the deliberative process and criteria that will lead it to decline to issue a certificate; and (c) the relative weight it attaches to each evidentiary requirement and to each of criteria comprising a requirement.

II. Alternative evidentiary requirements and criteria (2)- Proof of identity- Article 1.2(d) to (g) inclusive [59]

With respect to Article 1.2(d), it is a sad but a true fact that Ladino, or more correctly Judeo-Spanish, is a highly endangered linguistic species. For all intents and purposes, in the Sephardic communities, the language has become or is fast about to become exclusively the lingua franca of the seniors, as it would appear that most of the parents, especially those in mixed marriages, are not particularly keen to teach the language to their children, and quite independently of that, their children show no particular interest to learn it. [60] In the result, the younger generations of applicants already have a hard time and with the effluxion of time, will find it even harder, if not impossible, to establish the required proof under both the heading of Sephardic identity and that of personal connection to Spain.

Furthermore, the language requirement is vexatious in light of the admissions in the Preamble of the law that “the sons of Sefarad” maintained an immense nostalgia for Spain that occupied a place of first importance immune to the succession of languages and generations and sustained it by preserving Ladino.[61] It is trite law, at least in the English common-law system and tradition, that as a general rule, the Preamble to a general legislation is not part of the legislation proper and may not be resorted to in the interpretation and application of its provisions. Nevertheless, I find it objectionable for the legislation to dwell on this requirement contrary to the unqualified assertions made in the Preamble. The alternative criteria under the requirement are equally vexatious for applicants of the younger generations.

The requirement set out in Article 1.2(e) comprises three alternative criteria: (i) proof of registration of birth; (ii) the production of a Ketubah, or (iii) a marriage certificate which attests that the marriage was celebrated according to the Castilian traditions. The second criterion discriminates against (a) the Sefardies in mixed marriages; (b) the Sephardic couples who do not live in traditional societies and communities or simply chose, for whatever reason, to have only a civil marriage, and in any event, prefer to have a secular marriage contract governed by the laws of a particular civil jurisdiction of their choice The third one concerning the marriage certificate is both discriminatory and vexatious since all the expelled Jews did not originate from areas where the matrimonial customs were those of Castile, as was, for example, the case of the Jews expelled from Aragon and of the members of the centuries-old Jewish community of the Muslim Kingdom of Granada captured shortly before the expulsion.

Article 1.2(f) sets out the criterion of surnames. Elias Bendahan notes that Spanish law gives weight only to surnames that are both historically and presently and unequivocally Sephardic but that names that are typical and characteristic of a Sephardic lineage of Spanish origin are acceptable as evidence.[62] On this matter, Spain has summarily rejected the use for evidentiary purposes of any lists of Sephardic names as proof of the Sephardic identity of the applicants whose surnames are entered on such lists. The Article in effect sets out the latter test and requires “informed evidence” provided by an organization with “adequate credentials” setting out the grounds on which the applicant’s surname pertains to a Sephardic lineage of Spanish origin. [63]

It is reasonable to anticipate that a large number of applicants will encounter problems in satisfying this criteria, for a variety of reasons, including the facts that a lot of Sefardies, like the Ashkenazim of previous generations at some point in time in the past and unknown to the applicant, have felt compelled to change their names (a) both anxious and keen, as they were, to integrate into the dominant society of the country (and in many cases, consecutively to more than one) to which they immigrated or where they sought refuge; (b) in response to the not so subtle reactions to the names by members of the dominant society in the receiving country or region thereof; (c) comply with policies or legal requirements concerning the choice and change of names to avoid harassment and, at times, violence, and corollary to that (d) in order to avoid being noticed and to be able to circulate, as much as feasible, under the radar in countries infected by xenophobia, chauvinist nationalism, or religious intolerance, all of which usually goes hand-in-hand with anti-Semitism.

F. Evidentiary Requirements (3): Personal Connection to Spain-

Article 1.3(a) to (f) inclusive[64]

As is the case with each of the two evidentiary components of the evidence of Sephardic identity, the decision as to whether an applicant meets the requirements of this Article is made on the whole of the evidence submitted exclusively under this heading, regardless of the elements of proof provided under Article 1.2 even when they are relevant to Article 1.3.

Article 1.3 (a) which requires proof that the applicant has engaged in the study of Spanish history and culture, will disqualify a substantial number of applicants who (a) did not and still do not have the luxury of time to study it both timewise and in monetary terms; or (b) do not have the intellectual wherewithal to undertake such studies for the specific purpose of applying for Spanish citizenship; assuming, of course, that such study programs are readily available in or within a reasonable distance of the areas where they reside.

Again, for the reasons outlined with respect to Article 1.2(d), it is fair to question the requirement of Article 1.3(b); namely, possession of “accredited” knowledge of Ladino or Haketia which is discriminatory. It is also wasteful and vexatious because save for (a) applicants raised in Ladino-speaking families, who were taught the language and became reasonably proficient at it and b) those who have a professional or personal interest in Ladino, in the ordinary course of events, people are not known to show much, if any, interest in acquiring a dying or a dead language in the country, region or community where the applicant happens to live.

The requirements set out in Articles 1.3 (c) and (d) overlap with those in Article 1.2(f) under the heading of “Sephardic identity.” The former are as relevant, if not more, to the issue of identity than to “personal connection” and could have been used as an alternative to 1.2(f) or better still merged with it, at considerable savings for the applicants.

I submit, that in the circumstances it would have been far more reasonable , inclusive and cost effective to combine the proof of identity and personal connection under a single heading, as was the case under the previous regime and, in the process, reduce the total number of requirements and criteria while combining the optional evidence clauses 1.2(g) and 1.3.(f). In this regard, once again, the legislative scheme is both overdone and wasteful.

Worse, save for the two examinations, the overall scheme of requirements and alternative criteria creates a great deal of uncertainty for the applicants since they have no idea as to the relative weight that will be assigned to each of these and therefore will not be able to take this important factor into account in selecting and assembling their evidence.

G. Evidentiary Requirements (4): Two Mandatory Examinations Developed and Administered by the Cervantes Institute[65]

These examinations are mandatory subject to the following exceptions: The adult nationals of countries and territories where Spanish is the official language are exempted from writing the language examination, while minors and persons with incapacities are exempted from both but are required to provide instead, a variety of certificates depending on their status as a minor or an incapacitated person.

I. Knowledge of the Spanish language

The object of this examination is to determine whether the applicant possesses knowledge of the Spanish language as a foreign language at level A2 (basic) or higher, in accordance with the standards established by the European Council.

This examination is vexatious, in the light of the fact that the Preamble describes Ladino as a “Castilian language [66] enriched by imports from the surrounding languages” (Italics mine). It is so because this requirement requires the applicants who can speak and write every-day Ladino, to undergo the language test for it in addition to having to satisfy with the other Ladino related criteria. At all events, surely, an applicant who speaks Ladino will be able to communicate with Spaniards, as I do with my patient and helpful Spanish-speaking acquaintances, who are always at the ready to lend me tactfully a missing word or phrase here and there as needed.

This requirement (a) is wasteful of the time the applicants will be required to devote to the preparation of the examination and of the expenses they will have to incur in preparation for this examination; (b) discriminates against applicants who will find it difficult to satisfy this requirement by reason of a number of factors such as old age, lack of time, funds or education; and finally (c) is superfluous for the applicants who have no intention of settling in Spain and otherwise have no practical use for it.

Insofar as the applicants who intend to settle in Spain are concerned, based on my experiences and observations as a long-time immigrant to Canada, it is self-evident that the Spanish government does not appreciate the strength of the motivation and drive of the immigrants to learn the language of their adopted country and the speed at which they do so, particularly if they already speak a variant of Spanish or a related one in the group of Romance languages, or more importantly are anxious to get a job.

The fee for this examination for each applicant is computed by a prescribed formula. The Institute obligingly provides the applicable fee on a case-by-case basis upon the applicant electronically inputting the required information to a table found at the Institute’s website concerning the language examination.

II. Knowledge of the Constitution and of the “socio-cultural reality” of Spain

The object of the second examination (CCSE) is to determine whether the applicant possesses the requisite knowledge of the Spanish Constitution and of the Spanish “socio-cultural reality”.

The requirement concerning the Constitution is confounding. Save for an academic or other professional interest in the subject, why would an applicant who lives in another country know, would want to know or, for that matter, care about the Constitution of Spain? The subject is as esoteric as any subject can be, even for most lawyers who do not practice in this area of the law. Surely, if the ordinary folk of Spain are like those of other countries, Canada included, they also would be hard put to answer even some basic question regarding the Constitution of Spain.

As for knowledge of the socio-cultural reality of present day Spain, presumably in accordance with the politically correct view of this reality, it is a trite but true proposition that most reasonable people who are considering settling in another country would first check out this reality as well as the economic one on the ground. And if they are Jewish, they would also instinctively want to determine whether the country suffers from Judeo-phobia for religious, cultural, economic or political reasons, various combinations or permutations of these or for that matter, sometimes for no reason save to gain acceptance into a group and to retain its membership.

Ultimately, the perception and interpretation of the socio-cultural reality of a country is not found in the expected answers to examination questions provided by the Cervantes Institute but in the personal impressions and opinions of each applicant. And when it comes to the issues of adaptation and integration into Spanish society, these impressions and opinions, more often than not, become self-fulfilling prophecies.

In the premises, this requirement is frivolous, wasteful for the foregoing reasons and discriminatory for the various classes of persons with limitations of one kind or another identified above.

By way of consolation, the websites of the Cervantes Institute are extremely well organized and helpful. They provide (a) answers to all the reasonably pertinent questions the applicants may or can think of; (b) tools to prepare for the examinations including two glossaries: one for terminology (translated into English, French, Portuguese, Hebrew, and Arabic) and one for Spanish grammar, that are provided (c) free of charge to the applicants registered with the Institute, plus (d) electronic access to a 90 page manual containing 300 questions, 25 of which constitute part of the CCSE examinations administered during 2015.[67]

The fee for this examination is 80 Euros and allows the candidate to write the examination twice.

III. Assessment of the outcomes of the examinations

Based on my personal experience, the potential and actual candidates will be disappointed to learn that the Cervantes Institute does not post meaningful statistics concerning the outcomes of the examinations administered to date that would identify the nature of the impediments to taking and succeeding in each of these two examinations.[68]

H. The Legislation Revisited (1): The False Promise of Restitution and the Ultimate Perverse Irony

1. The false promise of restitution

As noted above, the legislative scheme has been characterized as an act of redressing an historical injustice by the restitution of Spanish citizenship to the descendants of the Sefardies expelled over five centuries ago.

The legislation, whatever else it is or might be, I submit, does not amount to an act of equitable restitution by any stretch of either legal or lay imagination. This is because the so-called restitution is made only to the descendants who can satisfy the unilateral and in many instances, frivolous, vexatious, wasteful, discriminatory or purely arbitrary requirements and criteria of proof which the applicants must satisfy without any regard to the effluxion of time and the present socio-cultural realities of the Sephardic Diaspora. In effect, to a considerable extent, the legislation freezes in time the image of the Spanish Sefardies in 1492.

The government and Parliament have done so, conveniently forgetting that it was the Spanish government that unjustly expelled their native sons and daughters because they happened to be Jewish; forbade them to return; decreed the death penalty to those who did and severed all contacts with them during the ensuing nearly three centuries;. More importantly, the restitution was to be for the unjust expulsion and not for what the expelled did or failed to do after their expulsion to remain faithful to their historical image in the minds of the Spaniards.

As Jorge Rosenblum, Director of Radio Sefarad aptly and succinctly put it “restituir no es conceder” (to return something/ to restore rights is not to give/award or bestow). [69]

2. The ultimate perverse irony: the legislation is a replay of 1492

In effect, under the heading of “personal connection to Spain” including the two prescribed examinations, the law provides for the restitution upon officialdom being satisfied that the candidate is personally suitable to become a Spanish citizen i.e., able to integrate into the present day Spanish society. In the premises, the law refuses to make restitution to applicants adjudged to be unsuitable according to these so-called “objective” standards, to borrow the exact term used by the government when it published the proof required under the first Bill. More importantly, just as it was done in 1492, the law establishes the grounds on which the descendants are to be further deprived of the Spanish citizenship.

To put it differently, the legislation provides the grounds to justify a modern day constructive exile. And once again, as was originally the case, the ground for the latter exile is being “different” than members of the dominant society: originally it was the religious difference, now it is failure to prove the continuation of what once existed or the hypothesized cum theorized inability of applicants to integrate, and preferably assimilate, into the present-day Spanish society.

Hence, contrary to all the assertions to that effect, Spain has not opened its arms to the descendants of those once expelled but only to those descendants it now considers to be suitable cum desirable for Spanish citizenship on the basis of the foregoing requirements of the law.

When on November 30, 2015, on the occasion of the celebration of the enactment the new law held at the Royal Palace, King Felipe VI said to the Sefardies in the audience and at large “How we missed you!” In fact His Majesty did not mean to say that He missed all the descendants, nor even the direct ones. Surely, what he actually meant to say was ‘how we missed those descendants whom the law in 2015 considers favorably whom We are now prepared to have in our midst!’ [70] (caps because kings and queens always speak in the first person plural).

By way of illustration, let us examine the facts of the recent case of the couple Joseph and Doreen Alhadeff .Both are Sephardic Diaspora Jews living in the United States. Doreen became the first Jewish American to obtain Spanish citizenship under the new law. She learned Spanish during her college years in Spain, However, Joseph who did not take a Spanish language course during his studies or otherwise, does not speak it and therefore, will not be able to pursue his application for the citizenship until he manages to pass the language examination. Consequently, here we have two genuine Sephardic descendants and while one got in, the other will be kept out until he passes the language test without any guarantee that his application will eventually succeed.

This is not to suggest that the government ought to grant citizenship holus bolus to any or all comers as and when they want to become citizens. Clearly, by definition, a sovereign country is entitled to control and defend its borders against all comers and to specify the criteria which they must meet to become citizens.

Rather, my point is that the population we have here are not indistinct lately newcomers. These are the descendants of subjects who were home to begin with. Hence, having regard to the unusual historical circumstances which the legislation purports to address, and to the claim of the government that the law has been enacted to correct an historical injustice by restoring the citizenship unjustly revoked from those expelled to their descendants, what is called for is a different set of evidentiary premises to frame the legislation.[71]

More specifically, these premises ought to be, first, a minimalist, sensible and sensitive approach to evidentiary requirements, providing suggestions but allowing every applicant the opportunity to provide the evidence, acceptable under the Spanish law, which she or he considers to be probative; and second, the nature and scope of evidence required ought to be such as to equalize the opportunities (a) to secure the citizenship among the applicants without regard to their respective age; state of mental and physical health (short of mental and total physical incapacity); level of education; profession, and financial resources and (b) to eliminate otherwise avoidable discriminatory practices and in default, to provide compensatory concessions. [72]

J. Procedural Issues [73]

I. Time-frames guiding the application process

The time-frames are set out in the legislation. More specifically, (a) Article 1 grants interested persons the right to apply for Spanish citizenship within three years from October 1, 2015.This deadline may be extended by one year with the consent of the Cabinet;[74] (b) Article 2 requires the applicants to be notified of the decision to accept or reject their applications, within one year upon the completion of all the interlocutory (intermediate) procedures, when the files are remitted to the DGRN, the authority entrusted with the administration of the application process that ultimately rules on the merits of each application by issuing a written decision outlining the grounds on which the application has been granted or rejected, and notifies the applicants accordingly by serving them with a copy of the decision.

These time-frames are subject to two exceptions. The first of these addresses the case of applicants who have already secured all the requisite proof that would entitle them to obtain the citizenship but fail to meet the prescribed deadlines in situations where exceptional circumstances or humanitarian considerations exist. In such cases, the applicants who secure the endorsement of the Minister of Justice are permitted to submit their applications directly to the Cabinet.

The second exception addresses the application of the provision of the law that requires a particular class of incapacitated applicants to be provided with reasonable accommodation in order to afford them the right of equal access to citizenship,[75] certainly a positive improvement over the pre-existing regime prior to 2013.

The one important missing piece of information concerns the ultimate permissible total duration of the interlocutory and final proceedings concerning the assessment of evidence, having regard to the potential complications that may arise. These are addressed below in sub-part III.

II. Significant departures from the pre-existing procedures (1): Processing the applications

The procedures prescribed by the legislation for the processing of the applications represent a significant departure from those used under the previous regime. More specifically, while the previous regime enabled the applicants to pursue their applications through the local Spanish consulates of the country in which they resided, the process under the new law is wholly computerized, managed and administered centrally in Spain by the DGRN. (Article 2.1) Accordingly, the applicants who find it difficult to handle the new system will be forced to incur additional expenses to hire the services of legal counsel or a para-legal proficient in Castilian and in the use of computers in these types of cases to handle this part of the process.

III. Significant departures from the pre-existing procedures (2): The division of the task of assessing of the sufficiency of the evidence submitted by applicants into a hierarchy of levels

A further departure from the pre-existing procedure is the division of the task of assessing the sufficiency of the evidence submitted by applicants into a hierarchy of two levels.

1. Procedures and process at the first level: The notary’s assessments and the hearing before the notary [76]

Article 2.3 requires the DGRN to transmit the applicant’s file to the General Council of Notaries (“GCN”) which in turn assigns it to a notary after taking into account the applicant’s (unspecified types of) preferences, presumably one of which would address the question of the location of the hearing.

a) The preliminary assessment of the application

Upon receipt of the file, the notary is required, within the next 30 days, (a) to conduct a preliminary review and assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the evidence submitted with respect to both the Sephardic Identity and the personal link to Spain and (b) to make a preliminary determination as to whether the evidence is ex-facie adequate to meet the requirements of the law under both headings.

Where the notary reaches a negative conclusion with respect to one or both of these matters, he is required to write a reasoned report and submit it, along with the file, to the DGRN.

In the event the notary reaches an affirmative conclusion, she or he is required to (a) request the applicant to attend the mandatory hearing over which he or she will preside and (b) issue a formal invitation to that effect, and (b) provide the necessary documents to the appropriate authorities in order to insure that the applicant is able to enter the country.

b) The hearing before the notary

A regrettable feature of the hearing is that the applicant is not afforded the opportunity to make a choice between being represented at the hearing by a lawyer or a lay person or a trusted friend who is very knowledgeable not only about Spanish citizenship matters but also in dealing with evidentiary issues, and in particular those arising from the expert evidence, and would probably charge much less than a lawyer or nothing more than the costs of travel, if any. The lawyers enjoy a monopoly.

Nor is it clear whether the applicant may appear accompanied by a lawyer and/or a translator.

The applicant then must elect either to attend the hearing in person or to retain a lawyer to appear on his or her behalf. (Article 2.3) for a variety of reasons, such as the imperative need to avoid the anticipated levels of stress expected to be caused by the appearance, for example, due to the applicant’s old age; physical or mental health condition short of legal incapacity; limited education; a temperament unsuited for such occasions or linguistic limitations.

However, for the time being, the applicant’s attendance at the hearing must be considered to be of capital importance until such time as the applicants and counsel appearing at such hearings acquire and disseminate their knowledge of and experience with the notarial process to confirm or infirm the validity of this proposition.

During the hearing, the applicant, or counsel on his or her behalf, must present the originals of the documents submitted under Article 1 together with any translations prepared with respect to one or more of these, all in accordance with the technical evidentiary requirements prescribed by the law. The provisions concerning the proceedings before the notary are also silent as to whether during the hearing the applicant is at liberty to submit additional documents.

The applicant is further required “to state, in accordance with her or his responsibility before the notary” (as the statute phrases it) that he “is sure that the facts on which his application is based are accurate.”

The hearing, inevitably affords the notary the opportunity to observe the demeanor of the applicant and to test and assess the credibility and related issues.

Upon conclusion of the hearing, the notary must submit to the DGRN a reasoned report (curiously enough, within an unspecified deadline) that assesses the merits of the application or the lack thereof and transmits it together with the full file.

2. Procedures and process at the second and determinative level: The decision of the DGRN

Upon receipt of the notarial report, the DGRN is required to seek promptly the police and other reports from relevant units of two departments, to write the determinative decision to reject or approve the application and to notify the applicant accordingly. Strangely enough, for a modern piece of legislation and, at that, one with respect to which the outcome of the application is of considerable importance to the applicant, it contains the proviso that in the absence of such notification, administrative silence is to be construed as the rejection of the application.[77]

3. The rights of the applicants and the powers of the DGRN with respect to the notarial process

The legislation is silent as to whether (a) the applicant is entitled to receive copies of the reports submitted by the notary and if so, the time frame within which the reports must be delivered; and (b) the DGRN is entitled (i) upon receipt of the preliminary or the final report , to direct the notary to reconsider the evidence and submit a new report;(ii) to direct the notary to revoke or extend an invitation for a hearing, as the case may be, or ( iii), to remit the file to the GCN with a request that the matter be re- assigned to another notary, and at all events, (iv) to override or ignore the notarial report in part or in whole in writing the final decision.

4. Appeal against adverse decisions

The legislation does not address the matter of judicial recourse against adverse decisions. Instead, it merely refers the reader to the pertinent legislation in administrative law dealing with the review of quasi-judicial decisions of this type; a subject outside the confines of this paper.[78]

IV. The Challenges created by the new adjudicatory system: The issue of consistency in handling the evidence: fact-finding, assessment and decision-making

1. At the notarial level

The work of notaries during the roll-out of the legislation may be reasonably expected to be fraught with a number of difficulties (and inevitably, hazards for the applicants) . The most critical ones are those associated with the imperative requirements for every notary to be:

Firstly, self- consistent in (i) the interpretation and application of the law ;(ii) dealing with procedural matters; (iii) reading, weighing and assessing the evidence; (iv) the manner in which the hearing is conducted and the applicants and their counsel are handled and treated, and (v) in the writing of reports ; and

Secondly, consistent in all these matters with the manner in which the other notaries are handling their respective files.

Furthermore, in order to achieve these objectives individually and collectively, it will be imperative

a) to designate a person or group of persons to spot individual and collective inconsistencies, without undue delay, as and when these crop up; to resolve them according to law and to disseminate the outcome to the notaries and the DGRN.; and