The Multiple Risks that A.B. Yehoshua Takes in his Novel Mr.

Mani

By

Judith Roumani *

A.B.Y. needs no introduction, being one of the best known Israeli novelists, not always recognized as being Sephardi. He is definitely Sephardi on both sides of his family, his mother being from Morocco, and his father from an old Jerusalem family. Perhaps having obtained the heights of literary success in Israel somehow makes many people assume he must be Ashkenazi.

Even though he is part of the establishment, he has still endeavored to take risks in many aspects of his public expression. He has incurred the ire of American Jews by his statement that one cannot be fully Jewish unless one lives in Israel. This position has some support from Jewish orthodoxy, which maintains that certain halakhot can only be performed in the Land of Israel. If we look in that direction, though, for the inspiration for his ideas, we are on the wrong track. Yehoshua is an admitted atheist. His idea that one can only be fully Jewish in Israel is a deeply meditated outcome of his secular Zionism.

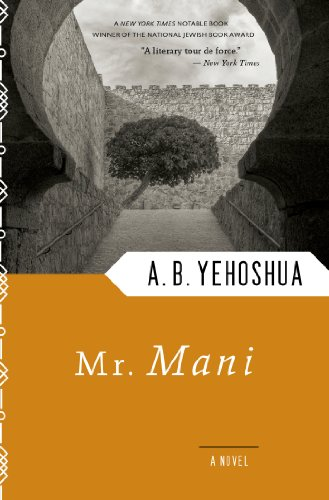

Yehoshua is also staunchly on the Left in Israeli politics. This paper, though, is not about his political views but rather about his novel, Mr. Mani, published in 1990 in Hebrew and in 1992 in an excellent English translation by Hillel Halkin.

In his earlier novels he examined present-day reality. Mr. Mani is the first of several of his novels that delve into history, Yehoshua believing that one cannot understand the present, without understanding the past. But writing a historical novel is a risk in general; readers shy away from non-contemporary settings, finding the effort to understand another historical period something they would rather skip. Yehoshua’s novel begins in 1982, and covers five turning points in history, proceeding back through 1944, 1918, 1899, and 1848. He covers several generations in one Sephardic family of the Eastern Mediterranean. We notice that he begins with the very recent past and proceeds backwards to the source of this family’s recurring issues. That technique in itself is not unique. Nevertheless, for readers who are used to contemporary realism from Yehoshua, the basic structure as a historical novel delving back into the past, going down through the layers of history, can be risky and off-putting. Many historical novels do not achieve a large readership in English-speaking countries, but Israeli readers are different, and the response to Mr. Mani was incredible (seventy articles on it within three years. “This novel has been a remarkable cultural phenomenon in Israel. By 1995, a mere five years after the novel was published, two collections of reviews and essays, containing more than seventy articles, had followed in the wake of intense discussions and conferences that greeted the novel in 1990” (writes Bernard Horn).1 The full publication of the novel in English in 1992 was preceded by a chapter published in the New Yorker, quite a coup for a foreign language novelist.

Yehoshua has since published two more novels centered on Sephardic history. Herein lies another risky strategy, for the history of Sephardim is far from a central issue in the minds of his traditional Israeli or even foreign Jewish readership (often Ashkenazim). Moreover, the obscure historical terminology, not to mention the issues preoccupying his characters, such as whether a particular action is or is not a sin disqualifying the character from life after death, a question only the most learned rabbi of the pre-modern age is able to answer, and Yehoshua’s rich but obscure Hebrew vocabulary and syntax, are also major risks for losing his loyal audience.

We next turn to Yehoshua’s extremely reader-unfriendly strategy in literary technique. The novel consists of five “Conversations” each from a different era. The subjects, as we know, are various members of the Mani dynasty, but only in the oldest conversation does a Mani actually take part. All the other conversations are between persons who know a Mani well, somewhat, or not at all. The recurring motif throughout the novel of a mirror reflecting the image in another mirror is an apt representation of this technique. Moreover, we are only privileged to read one side of the conversation, which is like listening in on one side of a telephone conversation. This requires active reading, where the reader contributes his or her understanding and is in a sense a co-creator, or co-conspirator, in the novel, or accessory to the crime, if crime there is. In the last conversation, Avraham Mani is speaking, but for most of it he is speaking either to the impatient rabbi’s wife, or to his rabbi, who has been rendered speechless by a stroke, and at a certain point in the conversation (we don’t know when) dies, so that the last part of the conversation is with a corpse.

This brings us to the question of crime, and to the greatest risk that Yehoshua takes in this novel. Several critics have remarked on Yehoshua’s interest in the biblical story of the Binding of Isaac, in Hebrew the Akedah.2 In the Fifth Conversation, the bible and Freud intersect, as Yehoshua rewrites both the Akedah and the Oedipus complex. Sephardim and Ashkenazim place great emphasis on the story of Abraham and Isaac, in which following God’s bidding the father almost sacrifices his son. It plays a major role in the service of Rosh Hashana, in which Jews in preparation for Yom Kippur implore God to spare us in the merit of our ancestor Abraham. The instruction that Abraham has heard turns out to be false, however and, at the last minute he is told to stay the knife and sacrifice the ram caught in the thicket. After reading the passage on Rosh Hashana, Sephardim have the full agony and the poignancy of the event unfolded for us by a Spanish paytan, named perhaps Abbas Yehuda Shmuel, in the beautiful but sorrowful piyyut, in which the supposedly doomed Isaac asks that his ashes be brought to his mother so that she may scent “the fragrance of Isaac.” The obsessive refrain beats into our memory: “Oked ve hanerkad, vehamizbeach” [The Binder, the Bound One and the Altar] with its repetitive tune or maqam, one of the most beautiful piyyutim of Rosh Hashana. A midrash also goes that Sarah is brought the false news that Isaac has been sacrificed, and dies upon hearing it. Alternatively, according to some Ashkenazi rabbis, she commits suicide by jumping off a roof, because she fears that her merit was not high enough to merit God’s accepting the sacrifice of her son. Muslims believe that it was the older brother Ishmael, not Isaac, who was the son marked for sacrifice. Poetic traditions suggest that neither Isaac nor Ishmael was sacrificed that day, but that Abraham had a third son, who was the ram and was indeed sacrificed (Yehuda Amichai), and that since Isaac every Jew is born with a knife in our heart (Haim Gouri).

How is the Akedah presented in Mr. Mani? Avraham Mani, in 1848, has a confession to make to his rabbi, whose reassurance he craves. When Avraham Mani of Constantinople visits his son Yosef and daughter-in-law Tamara who live in Jerusalem, he senses that his daughter-in-law is still a virgin. Avraham’s son Yosef has had his mind infected by the idea that the Muslims living in the Land of Israel in 1848 are, as the descendants of Jews converted to Islam, actually “Jews who do not know they are Jews.” Avraham allows his son to indulge this belief for his own benefit, when he lets him assemble a minyan (of men who should be Jews, but are actually Muslims who have been bribed) so that he can say kaddish for his ancestors. This is the first sin that Avraham confesses to his rabbi, something that he had thought at the time to be insignificant, but which turns out to be proof of the root of Yosef’s obsession. Once in Jerusalem, Avraham perceives that his son has an ‘idee fixe’ that blots out all his other commitments, including those to his wife. He flits among the various communities, at home in all, coming back at all hours of the night, as his wife sleeps peacefully, and his worried father waits on the roof. There are many dangers for a Jew in 1840s Jerusalem and when Yosef eventually is found stabbed to death on the steps leading up to al-Aqsa mosque (built over the rock where Abraham almost sacrificed Isaac), suspicion falls on many groups. First, on the fanatical Christian pilgrims, then on the Muslim guards who guard the approaches to the mosque, and on a young sheik, who attends the shiva and whom Avraham several times calls “the murderer.” The guards who had captured Yosef had bound him up, rolled him down the steps, a knife flashed, and then Avraham arrives on the scene. Perhaps all these had a role. But Avraham gives himself away by saying that he himself gave his son the coup de grace.

The son and his ‘idee fixe’ are laid to rest on the Mount of Olives. After those accompanying the mourners have left for the night, and the father and widow have eaten the ‘”endless egg” prescribed for mourners, symbolizing a new beginning even in death, Avraham strips off his clothes and heads for his daughter-in-law’s bed, to plant seed in the name of the deceased. The young woman’s name is Tamara. In the bible we have two Tamaras: the first is the righteous daughter-in-law of Yehuda, and the other is the half-sister whom Amnon raped. Which Tamara do we have here? Rather obviously the first one, though Avraham still needs his rabbi’s confirmation that what he has done is not a sin. As Tamara’s pregnancy proceeds, Avraham remarks with satisfaction that “The world would have its Manis after all.”

The other aspect of Avraham’s behavior, i.e. contributing to the murder of his son, is far more troubling: and we never do actually hear what the rabbi thinks of this, as he is unable to speak. It is certain, though, that he understands, as his face and body show signs of disturbance just before he dies. As a renowned rabbinical judge perhaps he cannot find any justification for this sin and his death in shock is the rabbi’s answer. To compound things, after the rabbi’s death, Avraham contemplates proposing marriage to the rabbi’s widow, and is only deterred by her cold and severe attitude to him.

Avraham Mani is a complex, not very sympathetic character. He is

interfering and intrusive, and when he is not worrying about

perpetuating his own seed, is suicidal. He constantly refers to the

maggots that are everyone’s destiny. Why should we care about him?

Yehoshua explains elsewhere3 that he was extremely troubled by the Akedah. He calls it “this appalling story,” and states that “I wanted to free myself from the myth by bringing it to full realization.” This risky act of supreme chutzpah stems from what he sees as the immorality of the story, stating that a genuinely religious person cannot possibly accept this myth. This is Yehoshua’s motivation for having his fictional character murder his own son. “That which in the bible story was merely a threatened sacrifice would be turned into an awesome reality. And perhaps by actualizing the murderous threat I could discredit its appeal... This is what I refer to when I say I am annulling the sacrifice of Isaac by its fulfillment.” Religious Jews today accept the shock and awe of the Akedah story but draw on it for faith and a belief in God’s compassion for every generation.

Nevertheless, this chapter ends on several tragic notes. Avraham deserts his grandson/son, and resumes an itinerant life, being last heard of disappearing into a remote area of Mesopotamia (readers do not need reminding that this was the biblical Abraham’s land of origin). The rabbi’s wife and Tamara’s aunt finds out the truth and, after a short period of happiness with Tamara and the child, leaves in shock, to finish her life in Egypt. The father’s crime against his son thus has its due effects. The crime committed at the beginning of the Mani dynasty comes back to haunt them in each generation, in the suicidal tendencies of every Mani down to the present in this novel. One does not need to agree with Yehoshua4 to admit that the risks that he takes do force us not only to admire his virtuosity but also to think very deeply.

* Judith

Roumani is the founder and editor of the peer-reviewed online journal,

Sephardic Horizons, and author of a number of articles on Sephardic

literature, as well as two book manuscripts, and a translator, most

recently of the novel by

Albert Memmi, The Desert.

1. Bernard Horn,

“The Shoah, the Akeda, and the Conversations in A.B. Yehoshua’s Mr.

Mani,” pp. 136- 150, Symposium (Fall, 1999). See also Yael

Halevi-Wise, Interactive Fictions: Scenes of Storytelling in the

Novel (Westport, Conn: Praeger, 2003), p. 132.

2. E.g. in

relation to his earlier

Three Days and a Child.

3. A.B.

Yehohsua, “Mr Mani and the Akedah,” Judaism: A Quarterly Journal of

Jewish Life and Thought 50:1 (Winter, 2001), 61-65.

4. Rabbi Haim

Ovadia of Magen David Sephardic Congregation, MD, has shared some

lectures that he gave in 2015 on Ashkenazi and Sephardic approaches to

the Akedah. Basically, Ashkenazim, especially in times of pogroms and

martyrdom, when parents might first kill their own children then commit

suicide to avoid forced conversion, have accepted the desirability of

the son’s sacrifice (fulfillment in Yehoshua’s term). Also, during the

Holocaust years, the Akedah story was used to explain the Nazi genocide.

Sephardim have not accepted the desirability of the sacrifice. Yehoshua

thus seems to be taking more of an Ashkenazi approach by envisaging

fulfillment, but a Sephardic approach in envisaging the guilt entailed.