Discovering Moses Ezekiel

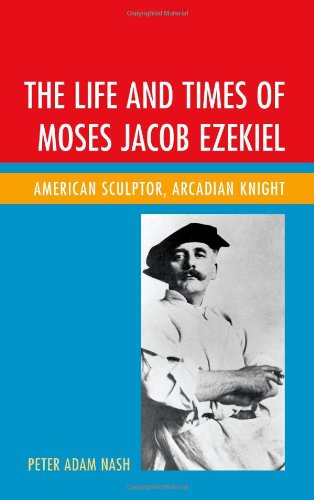

The Life and Times of Moses Jacob Ezekiel: American Sculptor, Arcadian Knight

By Peter Adam Nash

Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2014 ISBN 978-1-61147-672-9

Reviewed by Bension Varon*

The year 2017 is the 100th anniversary of the death of Moses Jacob Ezekiel. He was a Sephardic Jew of Dutch origin who was born in 1844 in Richmond, Virginia, fought in the American Civil War on the Confederate side, studied art in Berlin, lived and worked for over forty years in Rome, where he became one of the renowned sculptors of his time, and is buried in the Arlington National Cemetery. The centennial anniversary of his death in not likely to attract much national attention, because both his appreciation and his memory have faded, as his artistic approach, once greatly admired, has fallen out of style. The publication of Peter Adam Nash’s biography of Ezekiel in 2014 is, therefore, welcome. The basic facts of Ezekiel’s life were known before but lay scattered in sundry reviews, essays, letters, memoirs, and other archival material on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Nash pulls all of these together in one volume to present the first coherent biography of Ezekiel. His apparent aim is to reintroduce, reappraise and remember this bigger-than-life artist, updating and adding new material where necessary (although significant lacunae remain), and providing context. Nash does all this chronologically in nine chapters.

Chapter 1, titled “Spanish Roots,” covers the period from 1808, when

Moses Ezekiel’s paternal grandparents came from Holland to Philadelphia,

to 1844, when Moses was born in Richmond, Virginia. On arrival, his grandparents joined the Spanish-Portuguese Mikveh

Israel Synagogue (dating from 1740) in Philadelphia. Their son (Moses’ father) Jacob moved for economic reasons to

Richmond, where he married Moses’ mother, Catherine Myers de Castro, in

1835. She, too, was a

Dutch-Sephardi, and a member of a family of more recent immigrants. They

had fourteen children, of whom Moses was the seventh. The author opens the chapter with some background on the

well-known history of the Jews’ expulsion from Spain in 1492. Although this is useful, one would have preferred to learn more

about the Sephardic characteristics of Moses’ grandparents, paternal or

maternal. What language did they

speak at home, for example?

Nash says that they were “stubbornly nostalgic about Spain.” In what way, one wonders? Also, what influence, if any, did Holland have on Moses’

ancestors over the two centuries they lived there? Missing from this chapter and the rest of the book is something

I personally would have liked to see, an Ezekiel family tree.

[1]

Chapter 2, “Youth and War,” is devoted to the first twenty-two years of

Moses’ life. Moses spent the

first part of this period with his paternal grandparents in order to

alleviate his parents’ burden of raising fourteen children. Moses had no formal schooling, although he managed to educate

himself in history, literature, and even languages. It is also likely

that he received some religious education from his father and

grandfather, both of whom were observant Jews active in the community. This period also saw the beginning of Moses’ southern chauvinism,

which he would retain for the rest of his life. We learn that in 1861, at the beginning of the Civil War, he

“begged” his grandparents to enroll him in the Virginia Military

Institute (VMI) in Lexington, secretly hoping that it would be one of

the means of getting into the war.[2]

His wish came true: he was

accepted at the august institution. In 1864, together with other cadets, he was recruited into the

Confederate army and participated in the Battle of New Market against

the Union army. He returned

to VMI at the conclusion of the war to complete his studies and

graduated in 1866 with honors. In the same chapter we also learn that at age fifteen, before

entering VMI, Moses impregnated the family’s “mulatto” housemaid,

Isabella Johnson, who bore a daughter named Alice.

Moses maintained contact with

them whenever he could in the following years, but they were never

reunited. This chapter is in my view

the weakest one in the book, as rather than providing a critical

perspective informed by modern scholarship, Nash romanticizes the Old

South and the Confederacy.[3]

The next chapter (3), “Europe: The Awakening,” is about the launching of Moses Ezekiel’s career and reputation as a sculptor. Moses had studied anatomy in preparation for it at the Medical College of Virginia. When his family moved to Cincinnati for economic reasons in 1866, Moses moved with it and resumed studying art as a sculptor’s apprentice there. In 1869, he moved to Berlin, where he was accepted at the Royal Academy of Art—the prestigious Kunstakademie. He would spend the next five years in the German capital. Nash writes about those five years in what is perhaps the best chapter of his book. He does so in an objective, factual, journalistic way, without subjective embellishments. We learn about Moses being awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome, the first for an American, his receiving commissions from both within Europe and the United States, and his being accepted into German society. Nash also begins discussing Moses’ distancing himself from the emerging artistic trends, such as Impressionism, which he continues to do later.

The Prix de Rome award came with a two-year stipend for studying art in Rome. The next two chapters of Nash’s biography of Moses—“Ecco Rome” (4) and “The Baths of Diocletian” (5)—relate how, starting in 1875, Moses established himself in the city physically, professionally, and socially. Physically, he settled in a surviving stone structure amidst the ruins of the Baths of Deocletian dating from Roman times. He made the structure livable with the help of the local municipality, turning it into his home and studio. He would produce nearly all his major works, including those destined for the United States, there for the rest of his life. Professionally, he dominated the art scene quickly and for a long time. Socially, he interacted with the local American expatriate community, which included writers like Henry James, but more with the local elites. Nash writes that Moses’ studio soon became an artistic and a social center combined, and a must-see place to visit for U.S. and European dignitaries. The famous visitors to the studio over the years included former United States presidents Grant, Theodore Roosevelt and Taft (as private citizens), J.P. Morgan, J.D. Rockefeller, Mark Twain, Stieglitz, the Italian revolutionary Garibaldi, and Kaiser Wilhem II.

In the next chapter, “Swarming Beliefs and Causes,” Nash turns temporarily from Moses Ezekiel’s artistic activities to his personality. He discusses his beliefs in the occult, spiritism, transcendentalism, theosophy, and monism; his interest in Buddhism, Zoroastrianism and Hinduism; and his eclectic approach to Judaism, “comprised of facets both sacred and profane” (p. 99).“Remarkably, for all of Ezekiel’s fascination with the mystical and occult, he was stubbornly traditional when it came to his own Jewish faith, openly condemning what he considered ‘the operatic hats-off ape-ism’ of the increasingly popular Reform movement” (p.103). Nash stresses that Moses’ strongest beliefs and feelings were those he held toward his native state of Virginia and the Confederacy, which bordered on “religious devotion” (p. 100).

Nash points out that the final decades of the nineteenth century represented the most productive and the most successful of Moses Ezekiel’s life as a sculptor. He discusses that period in the next two chapters, focusing on the contrast between Ezekiel’s neo-classical style and the modernistic style of his contemporary Rodin. He comments on Ezekiel’s works, which won him wide recognition and awards, including the Cross of Merit for Arts and Science from George II, Grand Duke of Saxe-Meiningen, in 1887; the Golden Cross of the House of Hohenzolern from Kaiser WIlhem II in 1893; and the honorific title of Cavaliere Ufficiale della Corona d’Italia bestowed by King Victor Emanuele III in 1906. A highlight of the penultimate Chapter 8 is Nash’s account of Moses’ production of a bust of the Hungarian composer Franz Liszt for which Liszt posed in person. This took place in the Villa d’Este, where Cardinal Hohenlohe—a prior acquaintance of both Ezekiel and Liszt—lived at the time.

The book concludes, in chronological fashion, with Moses’ “Final Years.” It covers his death in 1917, at age 73, in Rome, the moving of his remains to the United States in 1921, and his burial, with military pomp, at the Arlington National Cemetery at the foot of the majestic Confederate Monument which he had built himself. The grave is marked with a simple plaque which reads: “Moses J. Ezekiel, Sergeant of Company C, Battalion of Cadets of the Virginia Military Institute.” The chapter notes the various accolades Ezekiel received from the highest levels of the federal and Virginia state governments and art scions. It concludes with what happened to his estate, which was modest. Nash provides information on what Ezekiel willed to whom carefully and lovingly, which puts a human face on this at times aloof and cold man.

Peter Nash’s biography of Moses Ezekiel raises several questions, some of which have been asked before but persist, nevertheless:

Why did Ezekiel’s reputation and memory fade so quickly and almost

totally after his death? And

why do we need to restore and maintain them?

How strong was Ezekiel’s attachment to, and identification with, the

Confederacy politically and philosophically?

What kind of a person was he? If he was enigmatic, as claimed, who was the man behind the

enigmatic façade?

How Jewish was he religiously and how Sephardic culturally?

I shall conclude this review asking: “What answers to these questions can be derived from the book, and how satisfactory are they?”

It is widely accepted that Ezekiel’s reputation faded because of his failure to keep up with artistic trends. Nash put this in a broader context, noting, “... [Ezekiel] twice came on the wrong side of history. The first time was as an ardent Confederate in the Civil War south, a war whose disgraced and defeated heroes remain unrecognized even today; the second time was when, as an artist, he chose Rome rather than Paris as his home, in this way, turning his back on the future of art itself, on the heady, restless innovations of such contemporary sculptors as Dalou, Brancusi, and Rodin. Instead, and for all his more progressive ideas about science and modernity, Ezekiel proved adamant in his devotion to the rigid, German-style neoclassicism that had earned him his name ... In what, by the final decade of Ezekiel’s life, was to prove the tidal wave of modernism, the once virile sculptor found he could barely swim a stroke” (p. xii). It is difficult to disagree with Nash’s harsh but correct assessment.

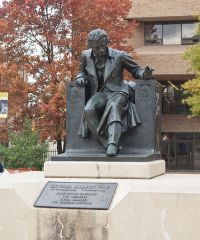

The reason for keeping the memory of Ezekiel alive lies in his legacy. As a sculptor, he produced more than two hundred works, some of which are truly monumental. The aforementioned Confederate Monument, to take one example, is 32.5 feet high, which makes it the tallest bronze structure in Arlington National Cemetery. In addition to thematic works, Ezekiel produced busts or statues, many of them life size, of famous men such as Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, Generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, Homer, Napoleon, Bismarck, Longfellow, and Edgar Allen Poe.[4] They are found in museums, art galleries, cemeteries, historic sites, state capitals, parks, universities, and private collections spread all over the United States: Charlottesville, Lexington, Norfolk, and Richmond in Virginia; Charleston in West Virginia; but also in Ithaca, New York City, Baltimore, Chicago, Louisville, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles. Everyday, hundreds of thousands of people are exposed to Ezekiel’s works, walk by them, stare at them, and admire them. All these people are entitled to information about Ezekiel, the artist-creator, through books such as the one reviewed here.

Moses Ezekiel identified at once with the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), his native state of Virginia, and the Confederacy. These identities were inseparable in their causes or origins, and he never wavered in his attachment to them. His strongest, purest and longest lasting attachment was to VMI—understandably so, since he lost ten fellow cadets in the Battle of New Market. He honored them in his masterwork Virginia Mourning Her Dead, his first statue, which he produced in plaster in Berlin and some thirty years later he cast in bronze and presented to VMI, where it stands today. Ezekiel’s relation to his state, the Confederacy and what it stood for—slavery in particular—is more problematic. Both Ezekiel (in his memoirs) and his admirers (in various statements and obituaries) have argued that Southerners were “instinctively opposed to slavery,” whatever that means, that they were concerned primarily with preserving states’ rights and free trade, and that Virginia joined the Confederacy late and reluctantly for these reasons. In his book, Nash seemingly buys into such myths. It is a well-established fact that secessionists in Virginia and elsewhere sought to preserve and extend slavery; on the eve of the war, Virginia was the state with the largest population of slaves and slaveholders, and one which exported slaves in large numbers to other states in the South. If Ezekiel truly had any misgivings about slavery, he joined the Confederacy despite its pro-slavery stance.

In the prologue to his book, Nash calls Moses Ezekiel “ ... a Sephardic Jew, homosexual, Confederate soldier, Southern apologist, opponent of slavery, patriot, expatriate, mystic, Victorian, dandy, good Samaritan, humanist, royalist, romantic, reactionary, republican, monist, dualist, theosophist, Freemason, champion of religious freedom, proto-Zionist, and proverbial Court Jew.” Yet he refers to him as an enigma, emblematic, and a puzzle of seemingly irreconcilable parts. In this reviewer’s view, he was none of the latter. One cannot have twenty-four known attributes and be considered enigmatic or unknown. He may be strange or chameleon-like but not unknown or unknowable. It is legitimate to ask, under the circumstances, what characteristics dominated and have affected Ezekiel’s actions the most. To his credit, Nash leaves it to the reader to form his or her picture of Ezekiel. For me, he was characterized by his stubborn and sentimental devotion to the past—not a vice in itself—and his individualism ... his courage to be different both artistically and personally.[5] A lesser characteristic was his penchant for self-promotion.

Ezekiel was a proud Jew who neither hid nor emphasized his religion. He devoted a few of his works to Jewish or Jewish-inspired

themes, among them the bas-relief

Israel, which won him the Prix

de Rome in 1873, and

Religious Liberty,

commissioned by the International Order of B’nai Brith for the

Centennial (1876)Exhibition in Philadelphia, which stands today in front

of the National Museum of American Jewish history in the same city. Nash notes that Ezekiel was an Orthodox Jew, although the

information is based on secondary sources.

More certain is Ezekiel’s

reluctance—indeed, resistance—to being identified as “a Jewish

sculptor.” He wrote

emphatically: “I must

acknowledge that the tendency of the Israelites to stamp everything they

undertake with such an emphasis is not sympathetic with my taste. Artists belong to no country and to no sect—their individual

religious opinions are private matters of conscience and belong to their

households and not to the public. . . . Everybody who knows me knows

that I am a Jew—I never wanted it otherwise. But I would prefer as an artist to gain first a name and

reputation upon an equal footing with all others in the arts circle. It is a matter of absolute indifference to the world if an artist

is a Jew or a Gentile”.[6]

Ezekiel was definitely of Sephardic origin. But how Sephardic was he culturally? Very little, but this needs to be placed in perspective. Nowadays, we tend to associate Sephardic culture with that of the Sephardim of the old Ottoman Empire. The Iberian Jews who settled in England, Northern Germany and Holland (or the Northern Sephardim) assimilated quite quickly. Their culture (including their everyday language, and liturgical practices and chants), therefore, evolved quite differently. Nash’s biography of Ezekiel contains no evidence that Ezekiel maintained any affinity to Spain culturally or otherwise. The only way Nash could link Ezekiel to Sephardic culture was through the link between his openness to ideas and Sephardic thinking of the same kind, which is a stretch. It would have been appropriate to refer to Ezekiel’s apparent facility for languages, a Sephardic trait not normal for the average American. In the final analysis, Ezekiel’s Sephardic character is more a matter of curiosity than of substance, for he is, as he would have formulated it, a noted sculptor who was a proud Jew (one of Sephardic origin) and the first Jewish cadet of VMI.

[1] Such a tree would have been doubly

useful, because, in his book, Mr. Nash identifies himself as “a

descendant of Moses Ezekiel” without providing any detail.

[2] VMI, which still exists, is a once

men-only state-supported military college founded in 1839 and

integrated in 1997.

[3] Isabella and Alice moved to

Washington, DC after the war.

As a young woman, Alice studied at Howard University,

becoming a teacher.

Isabella died in 1897.

Shortly after, Alice married Dr. Dan Williams, a

prominent African-American physician.

She died in 1924, leaving no survivor.

[4] Because of the biography’s

chronological treatment, references to Ezekiel’s works in it are

spread over the book.

For a more focused and in-depths treatment of Ezekiel’s

works, see Stan Cohen and Keith Gibson,

Moses Ezekiel: Civil War

Soldier, Renowned Sculptor, 2007.

[5]

Nash dwells on Ezekiel’s homosexuality more than

any writer on him, seemingly out of his resolve to treat his

life in depth, “whatever the aesthetic value of his life today.”

(xi) The recurring references to Ezekiel’s homosexuality,

including in the book’s back cover, are exaggerated and

potentially misleading, since there is no evidence that his

sexual preference influenced either his actions and achievements

or the way he and his art were treated by others.

[6] Ezekiel’s memoir, as quoted in

Nash, op. cit., p.104.

* Bension Varon is a retired economist with wide interests as a writer, including history, genealogy and biography. His extensive publications include Cultures in Counterpoint: Memoirs of a Sephardic Turkish-American (2009) and Fighting Fascism and Surviving Buchenwald: The Life and Memoir of Hans Bargas (2015).

Homer statue in front of Old Cabell Hall

at the University of Virginia

(Wikimedia Commons)

Homer statue in front of Old Cabell Hall

at the University of Virginia

(Wikimedia Commons)

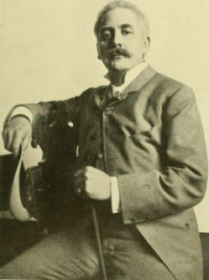

Religious Liberty commissioned by B'nai B'rith 1876

Religious Liberty commissioned by B'nai B'rith 1876 Moses Jacob Ezekiel 1914

(Wikimedia Commons)

Moses Jacob Ezekiel 1914

(Wikimedia Commons)