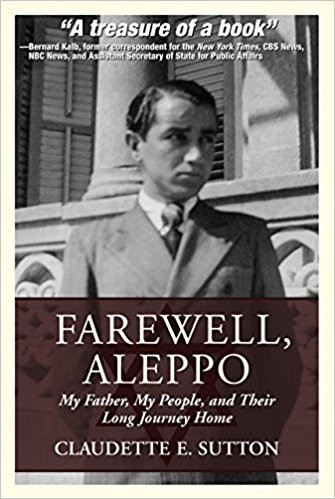

Farewell, Aleppo

My Father, My People, and Their Long Journey Home

By

Claudette E. Sutton

Santa Fe, NM : Terra Nova Books, 2014 ISBN 978-1938288401

Reviewed by Yaëlle Azagury *

In the aftermath of President Obama’s historic Cairo speech to the Arab world in 2009, the writer André Aciman wrote an opinion piece for the New York Times which pointed at one notable absence in Obama’s careful retracing of the region’s geopolitical complexities: “For all the president’s talk of “a new beginning between the United States and Muslims around the world” and “shared principles of justice and progress,” Aciman wrote, “neither he nor anyone around him, and certainly no one in the audience, bothered to notice one small detail missing from the speech: he forgot me.[…] or for that matter, about any of the other 800,000 or so Jews born in the Middle East who fled the Arab and Muslim world or who were summarily expelled for being Jewish in the 20th century.”

Claudette Sutton’s Farewell Aleppo, an earnest narrative about her family’s exile and odyssey from Aleppo, Syria via Shanghai to the United States in the 1950s and 60s strives to rectify this invisibility, in line with other narratives of Jewish exile from Arab lands, such as Aciman’s Out of Egypt, or Lucette Lagnado’s The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit. At a time when the question of Syrian refugees has provoked widespread outrage, there has been little mention outside academic circles about the Jewish exodus from that region of the world in the 1950s. In the interest of historical exactitude, recounting the trials and later the dislocation of the Syrian community—one of the oldest in the Middle East—enables us to document its nomadic history before it vanished in the midst of 20th-century political turmoil.

The American-born Sutton, editor and publisher of Tumbleweeds, a Santa Fe, New Mexico, publication for families, has pieced together the compelling trajectory of her grandparents, Selim and Adele Sutton, and their sons, Saleh, Elie, Meir (or Mike, the author’s father), Ralph, Joe, Morris and Edgar, and daughter Margo. Like many Middle Eastern Jews in that period, the Suttons were textile traders, importers of fabrics from Europe and neighboring countries. The reader follows them on a long exodus from Aleppo in the 1930s to Mersin, Turkey, and later to Shanghai in the 40s, Beirut, Israel, and finally the United States. This was a typical path for Jewish communities in the Middle East, as they sought to expand their economic viability, and gradually prepared to abandon their homelands in response to growing Arab nationalism and rising anti-Semitism in the Muslim world.

Rescuing her grandfather’s culture and way of life from obscurity is a worthy endeavor, but Sutton takes us most revealingly on a journey of self-discovery that is primarily her own. Here, she gradually comes to terms with her ancestry, which had never previously been central to her life: “I signed up for a course at my family’s synagogue to learn about my own background,” she admits candidly as she uncovers knowledge that any educated student of the region assuredly has. The reader should not expect groundbreaking research. (There are even some inaccuracies: the word consuegra is not Judeo-Spanish for mother-in-law, but a Spanish term used by one mother-in-law to describe the other; and Theodor Herzl wasn’t Swiss but Austrian).

Most of the facts related by Sutton are well-known: Aleppo was one of the oldest centers of Jewish life, and a renowned locus of Jewish learning by 1300: “This is the city mentioned in the Biblical legend of the prophet Abraham, where a Jewish community lived and thrived since Roman times.” So far-reaching was its fame that it became home to the most authoritative manuscript of the Hebrew Bible. Most notably investigated by the journalist Matti Friedman in a 2012 book, the story of the Aleppo Codex is shrouded in myth and secrecy: it is said for instance that if the manuscript disappeared from the synagogue where it was preserved, the Jewish community would cease to exist. As it happened, Aleppo’s ‘crowning glory’, as it was also known, vanished under mysterious circumstances after an Arab mob in 1947 stormed the site where it was preserved, and it reappeared ten years later at the Ben Zvi Institute in Jerusalem with dozens of pages missing.

Regrettably however, Jewish life in Aleppo in the 1930s and 1940s is painted in brushstrokes that are too broad, so the details provided appear by turns too general and pedestrian, or too distant to engage the author emotionally in ways other than as ethnological curiosities. Mercifully, the narration improves in the second half of the book, with the account of the brothers Saleh's and Mike's lives in Shanghai. The slow disintegration of French and British colonial rule in the Middle East, the shifts brought by World War II, and a more precarious environment for Jews, led Selim Sutton to “export his sons” to Shanghai, where they could join his brother Joe's textile business, shipping handmade linens from the Far East to markets in New York. Sutton movingly describes the boys' journey on their own from Port Said in Egypt to Shanghai, and her account of life in the expatriate community of 1940s Shanghai is vivid and intriguing. Mike’s resourcefulness also makes for a delightful tale. As the export business came to a halt because of the war, the author’s father reinvented his trade to survive. Instead of exporting textiles, he began speculating successfully in sewing needles, in short supply because of wartime demands for steel.

Far from home, exile gradually starts corroding the brothers’ identities in subtle and not-so-subtle ways. Saleh contracts tuberculosis, which will eventually kill him. Mike's faith, he tells his daughter, "just wore off.” He abandons kashrut. In the intimate observations of these immaterial shifts, the narrative starts charting more compelling paths. But expatriation comes with other intractable issues too. There is, for instance, the question of papers. As the Syrian government began tightening its grip on the Jewish community in retaliation to the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, those who had already left, like Mike, then newly arrived in the United States, were unable to renew their passports: “Without a valid passport, he could not extend his work visa, and as a Jew, he could not renew his Syrian passport or return home. In a nutshell, he was stateless.”

And when Selim Sutton, who had remained in Syria, is diagnosed with a brain tumor, he is only allowed a visa to Beirut, Lebanon, for treatment. Later he traveled illegally to Israel, where he died alone, and is buried in a cemetery outside of Tel-Aviv.

Sutton’s narrative, especially in its second half, effectively enumerates the many quandaries of dislocation. Her evocation of the little-known odyssey of Syrian Jews from Aleppo to America via Shanghai in the second half of the twentieth century is urgent and compelling. But the subject aches for a more poetic treatment, like that of Lagnado’s poignant meditation on loss, also centered on the figure of her father, or Aciman’s rich evocation of his family's complex characters in the waning moments of Egyptian Jewry. By contrast, Sutton’s account remains somewhat flat, her settings never sufficiently evoked, her voice disconnected from the accents of her subjects. And I wonder if therein lies precisely one of the most perverse effects of exile. As a descendant of those who left their homes, their cultures, and their countries behind, she did not experience this loss firsthand. She is visiting the culture of her forebears, but she has lost touch with it. The story she tells is as much the symptom as it is the remedy for that privation.

* Yaëlle Azagury writes about contemporary literature and Sephardic culture, which she also taught previously at Barnard College in New York. Her work appears frequently in the Jerusalem Post and other publications.