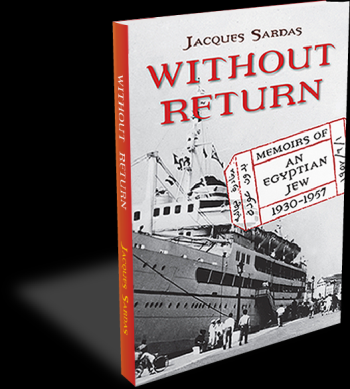

Without Return

Memoirs of an Egyptian Jew 1930-1957

By Jacques Sardas

Dallas : Thebes Press, 2017 ISBN 978-0998084909

Reviewed by Aimée Israel-Pelletier1

Today there are fewer than thirteen Jews living in Egypt from a population of about 80,000 in 1956. The youngest is in her sixties, making the present generation effectively the last. Egyptian Jews lived in Egypt without interruption for over 2, 000 years. As Geniza documents show and S. D. Goitein has argued, these Jews were a Mediterranean people embodying the open and mobile way of life associated with Mediterranean cultures. They were also Nilotic, experiencing a powerful sense of rootedness in the land of their biblical ancestors.

In 1800, Egypt’s population was about 4.5 million. A dramatic change took place starting in the first decades of the 19th century and continued through the 1930s.2 During this period, Egypt witnessed unprecedented economic growth and population expansion due to the modernization efforts of Muhammad Ali and his successors. It drew to its cities workers, craftsmen, engineers, and entrepreneurs from the northern Mediterranean, the Balkans, North Africa, and Anatolia. Between 1800 and 1957, the Egyptian population grew to 24 million. The population of Cairo, its largest city, grew twelvefold.3 Many Jews were among these immigrants. They sought opportunities to better their lives and contributed to Egypt’s phenomenal growth. Some returned to their homeland but most remained, as Egypt continued to prosper. Jacques Sardas’s memoirs, Without Return: Memoirs of an Egyptian Jew 1930-1957, is a homage to them. In this book, so well written that it reads like a coming of age novel, Sardas draws the portrait of a man from very humble beginnings, often going to bed hungry, who makes it to the top of the corporate world, is touted by Wall Street bankers, and featured in the pages of Forbes magazine. Jacques Sardas’s self-portrait is an emblematic representation of Egyptian Jewry’s entrepreneurial spirit, resoluteness, openness, and its resilience in the face of adversity. When Jacques left Egypt for Brazil at the age of 26, seeing no future for his family in Egypt, he was rehearsing an ancestral imperative, an imperative that went back generations to Greece and Turkey, where his father and mother were born, and further back to Moses and the patriarchs.

Sardas’s memoirs are compelling because he describes rather than explains, focuses on the reality on-the-ground. He handles political events deftly, like the Suez Canal crisis, the perverse tactics of the Egyptian police and customs officials, verbal and physical expressions of anti-Semitism by Muslims and others, the Cairo fire of 1952, and the multicultural landscape of cosmopolitan cities. He describes, with an eye to detail, family life and neighborhood life in the modest sections of Alexandria and Cairo where he lived. He brings readers along with him into classrooms with teachers, school directors, coaches, and classmates to illustrate how and what he learned. For example, at L’Ecole Cattaui, which he attended, the principal language of instruction was Arabic. He also provides remarkable stories of his life in Brazil after he leaves Egypt in 1957, describing the holding camps for immigrants, his pursuit of jobs and the process he undertook to secure them, what these jobs entailed, and how he failed and succeeded at them. We enter meetings with him and follow conversations.

Sardas writes with remarkable specificity and an economy of expression that wins the reader’s trust and emotional engagement. His passion for basketball is an example. It frames the first part of Sardas’s memoirs and gives the narrative cohesion, making for a lively reading experience. Besides illuminating Sardas’s character, his competitive spirit and natural leadership qualities, the narrative shows how the game of basketball was played in Egypt, who played and competed, how games were officiated, and how fans expressed their support. In a brilliantly handled scene, we learn how officials facing the potential win of the Jewish team managed the situation. They simply stopped the game and resumed it in a private setting. In the process, Sardas introduces Zouzi Harari, the Jewish basketball star who played for Egypt at the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, shows Harari in action playing the game and addressing his teammates. Albert Fahmy Tadros and Hussein Kamal Montasser, famous players on the Egyptian Army team, are described in a championship game against the Maccabis, the Jewish team, a game the Maccabis win. We learn that there was a Maccabi anthem and that it roused Jewish fans.

Another example is Sardas’s description of the military cemeteries near Marsa Matruh, south of Alexandria where he and Etty, his wife, spend their honeymoon. Sardas describes the cemeteries where Allied and Axis soldiers who fought in the battles of El Alamein and the siege of Tobruk are buried. He brings the reader to the very spot of the devastation: “The cemeteries faced each other on either side of a narrow gravel trail in the middle of the desert. Both cemeteries sprawled over a large area covered with endless tombstones. [...] Etty and I walked around both cemeteries. Most tombs had no names; several bore crosses, and a few bore the Star of David” (p. 183). He reveals the presence nearby of a small museum with displays of memorabilia from both sides of the war, letters home by soldiers and intimate objects. And he describes his encounters and conversations with Bedouins in the region. Sardas points out that after they were better acquainted, he confides to the Bedouins: “We are Jews.” The leader responds: “You know, this is how your ancestors used to live —as we do. After all, Moses was Egyptian; he was probably born east of here, not far away, closer to the Nile.” When Etty and Jacques ask the Bedouins how they survived when deadly battles were raging all around them, “they said that Allah protected them” (p. 185). Sardas comments poignantly: “What a contrast to the environment in Egyptian cities, where the government clogged the radio and newspapers with inflammatory messages” (p. 185).

Memoirists write to reconstruct their past, to pass down to future generations their stories, often hoping to strengthen their sense of identity. A few, like Sardas, understand further, as did the psychoanalyst Jacques Hassoun, also an Egyptian Jew, that every generation must create its own story in its own time. For a heritage to thrive, it is imperative that new generations engage with the present, allowing it to shape their perspective. In this project of transmission, each generation must receive from the generation that preceded it not only their story but also their blessing to be different. Sardas does this. In his dedication, after he pays tribute to his mother and wife, he continues: “And for my grandchildren and future generations, so they will know our story and be inspired to tell their own.” Sardas, in his early eighties when he writes his memoirs, does not conclude his story in a definitive way. Rather, he challenges himself to ask questions about his identity and his attachment to Egypt. In search of a perspective to help him deal with the cruelty of exile, very touchingly he draws a parallel between his feelings towards Egypt and his associate and friend, Chuck J. Pilliod, his “angel” the man who gave him his first ‘break’, and who suffered from Alzheimer’s disease. Sardas writes: “I accepted the fundamental changes that had altered his body and mind, but they did not change what he meant to me. Maybe I could think of Egypt the same way. It too had gone through fundamental changes, but they shouldn’t wipe away what the Egypt of my childhood meant to me. It was a beautiful country and had been an important part of my life” (p. 261).

It is not overstating the case to assert that many Egyptian Jews have a troubled sense of identity with respect to Egypt. Born and raised in Egypt (as Sardas was) how can they consider themselves Egyptian when Egypt itself did not and does not recognize their appartenance? Egyptian Jews are always mindful of the fact that they inhabited the very place their biblical ancestors had. As the title of Sardas’s book suggests, Egypt’s repudiation of its Jews is a betrayal, an injustice meted out upon a people that called Egypt home.

Besides being an excellent read and a source of information on Jewish life in Cairo and Alexandria in the decades before the crisis and near the end, Sardas’s memoirs offer an invaluable opportunity for readers to learn what is at stake when Egyptian Jews interrogate their identity, attachments, and address their grievance.

1 Aimée Israel-Pelletier is Professor of French and Section Head at the University of Texas at Arlington. She writes on 19th and 20th century French and Francophone literature and film. Her forthcoming book, On the Mediterranean and the Nile: The Jews of Egypt, published by Indiana University Press, will be released in March 2018.

2 James R. Cole, Colonialism and Revolution in the Middle East: Social and Cultural Origins of Egypt’s ‘Urabi Movement (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), p. 57.

3 Nancy Y. Reynolds, A City Consumed: Urban Commerce, the Cairo Fire, and the Politics of Decolonization in Egypt, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012), pp. 23-24.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800