Sicily, Land of Absences:

An Interview with Evelyne Aouate1 of

Palermo

Jews, Bnei Anusim and their descendants in Western Sicily

By

Judith Roumani2

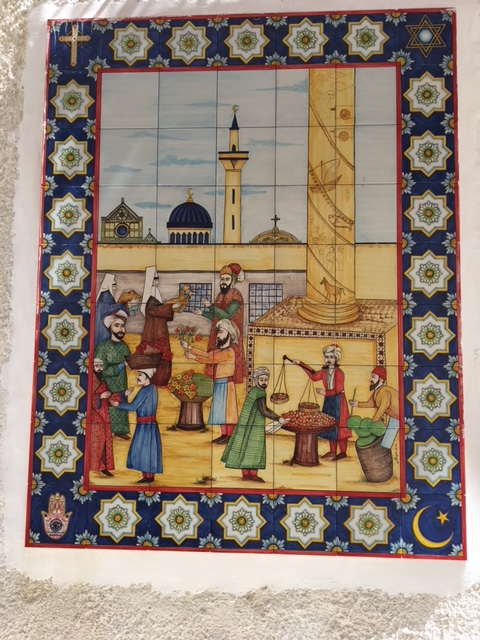

Wall tiles depicting a medieval marketplace with Jewish, Christian and

Muslim traders.

Symbols of the three religions surround the scene, and

in the background are a church, a synagogue and a mosque.

All photos by Judith Roumani

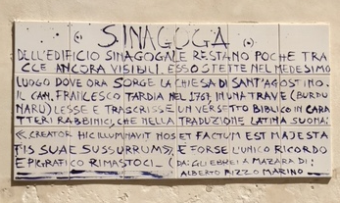

Plaque stating that there are few traces still visible of the building of the synagogue. It stood in the exact location where the church of Sant’Agostino is today.

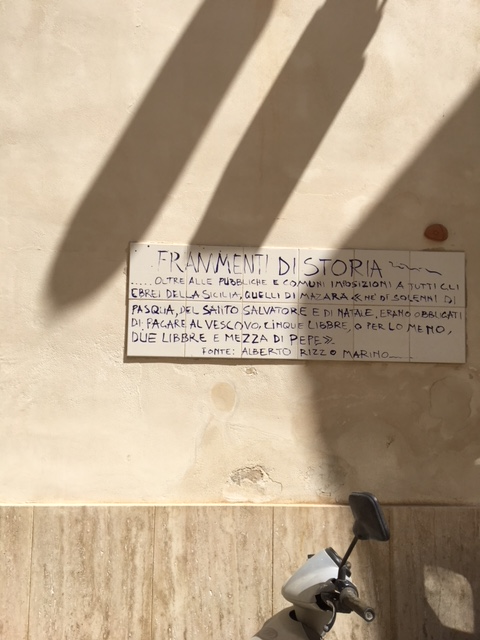

Fragments of history on a plaque: the Jews of Mazara were required, during the religious holidays of Easter and Christmas, to pay the bishop five libbre in coin, or two and a half libbre in peppers.

The far south-western tip of the triangle of Sicily in August: magnificent landscapes of dramatic dark mountains, dark sea and islands, black and white sands, dark green vineyards and parched, whitish wheat fields already ripened and harvested. Olive trees everywhere show the silvery white linings of their leaves at the slightest breeze. Among these magnificent contrasts of nature, one sees hardly a human being. It is a hundred years since the teeming families, unable to feed themselves from the land, emigrated to the Americas or to the Italian colonies such as Libya. Among the wheat fields, five out of six of the long-abandoned farms and small villages are in ruins; roofless, blank window openings allowing the sunlight and winds to pass through freely. The summertime four-month tourist invasion of Americans and Europeans from the north must only underline the desolation of the rest of the year.

Tourists come in search of this magnificent scenery, the olives, wine, fish and other taste experiences, as well as lavish archeological traces of earlier civilizations in Sicily: the Greek, Roman and Muslim sites. Sicily, almost a land bridge in the middle of the Mediterranean, has always been the crossroads of its civilizations. At the time of the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, Sicily was a possession of the Catholic Monarchs of Castile and Aragon, specifically of Ferdinand of Aragon, and thus Sicilian Jews fell under the decree as well. On a visit to Sicily, I managed to interview Evelyne Aouate, who is originally from Algeria and France but has lived in Palermo for fifty years. She points out yet another absence, due to the tragic expulsion of Sicily’s Jews. Though this absence can hardly be linked to archeological remains viewable today (except in the case of the ancient Mikvah recently discovered in Siracusa on the eastern side of Sicily) the former presence of thousands of Jews in Sicily has likewise left traces and repercussions even in our times.

A street near the former Jewish area, with tiles visible on either side.

Evelyne Aouate, founder of the Sicilian Institute for Jewish Studies, and a prime mover of current Jewish life in Palermo, kindly took time from her vacation in the Sicilian islands to give Sephardic Horizons a phone interview about the history and current situation of Jews in western and southern Sicily and in her own town of Palermo, where she has lived for many decades and is active in promoting the return of Jewish life.

Hamsa, a shared symbol.

She told us that Jews were in Sicily two thousand years ago, perhaps brought there as slaves after the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans. In the year 590, the pope issued a bolla (proclamation) declaring that the sacred ritual objects should be returned to the Jews of Sicily from whom they had been confiscated, thus implying that synagogues were in existence. The medieval Jewish traveler, Ovadia of Bertinoro, visited Palermo and noted that it had the largest synagogue he had seen in Italy. Sicily was under Christian rule, then Muslim, and then, by the fifteenth century, Spanish rule. It was ruled by the Catholic Monarchs, Queen Isabella of Castile and King Ferdinand of Aragon, and when the Decree of Expulsion was declared for the Jews of Spain in 1492, it also applied to those of Sicily. By that time there were fifty Jewish quarters, and about 35 to 50 thousand Sicilians (among the total Sicilian population of 150 thousand) were Jews. In the small town of Mazara in the far west and south of Sicily (where I stayed) fifty percent of the population was Jewish.

Thus much of the economy was dependent on Jews, including industries such as fishing, coral, and textiles.

Wall tile in Mazara possibly depicting Jews and Christians engaged in business in medieval times.

The application of the fateful decree was delayed for a few months in Sicily, in contrast to Spain, and the Jews were given until January 12, 1493 to convert or depart, but by December 31 most of the Jewish population was gone, leaving behind about 9,000 who chose conversion. These New Christians or neofiti as they were called in Italian, were from then on closely watched, sorvegliati is the word that Evelyne uses, for any outward signs of continuing loyalty to Judaism, and over the succeeding centuries about 1,800 were arrested and tried by the Inquisition. Conquerors came and went, but the Inquisition survived. Among the former Jews and their descendants some four hundred were executed, usually by burning at the stake. The same suffering, the same acute, unimaginable anguish, as the descendants of Jews experienced in Spain and Portugal and their possessions, for approximately three hundred years.

Among the Jews who left Sicily to avoid conversion, many went to Naples, Rome and northern Italy, and many others went to Salonika and the Ottoman Empire.3

She tells us that the Jewish community of Palermo had numbered between 5,000 and 9,000 before the Expulsion, and today we find only a very small community of Jews and Bnei Anusim. Evelyne Aouate’s institute has been compiling lists of Jewish family names in Sicily, to guide those who suspect they might have Jewish ancestors. Unlike in the rest of Italy, in Sicily Jews did not bear the names of places, but rather of professions, mestieri, or the names of aristocratic families with whom they were associated, or names such as ‘Benedetto’, which was a typical Jewish name (Baruch).

Rua della Giudecca, Mazara.

The surprising phenomenon of return to Judaism five hundred years after a person’s ancestors had converted can have one or more among several causes, Evelyne Aouate tells us. Sometimes a person expresses a vague dissatisfaction or discomfort with Christianity, and in other cases they feel a sort of mystical attraction to Judaism, or hear about unusual family practices, such as the inexplicable lighting of candles on Friday evenings, and spontaneously begin to do such things as studying Judaism or the Hebrew language. Very few have gone as far as actual conversion as yet.

The small Jewish community of Palermo meets for Shabbat celebrations in individual homes, as there is no synagogue as yet.4 The community is trying to raise funds for construction or renovation of a space being donated to them by the church. What is important in a country like Italy is that the community is officially recognized as a branch or ‘sezione’ of the Jewish community of Naples. It thus has the official blessing of the UCEI, Union of Jewish Communities of Italy. Rabbi Mino Bahbout, now the rabbi of Venice, was previously rabbi of Naples and the south. He was active in reviving the Jewish synagogue and study house of the southern town of Trani, and also in encouraging Jewish expressions across Sicily. There is no rabbi at present, Evelyne Aouate tell us, but there is a young rabbinical intern present in Palermo to organize services.

The good news, to take a somewhat larger view, is that Jews, Christians and Muslims have excellent relations in Palermo today, and hold friendly inter-religious events. They constitute an example to the world of inter-religious harmony today, in a place where hardly anyone would have dared to express allegiance to Judaism or Islam for five hundred years.

With profound thanks to Evelyne Aouate for sharing these observations with Sephardic Horizons, on Aug. 7, 2018.

The Church of Sant’Agostino, built on the site of the synagogue,

today boarded up and apparently under long term repair.

Further Reading and Listening:

Emerging Jewish Communities in Sicily, with Judith Cohen (Radio Sefarad)

History of the Jews in Sicily (Wikipedia)

Jewish life in Sicily reborn by Michael Freund - The Jerusalem Post September 15, 2011

PALERMO: by Richard Gottheil, Ismar Elbogen - Jewish Encyclopedia

The Jews of Palermo by Jacqueline Alio - Best of Sicily Magazine, 2002

1 Evelyne Aouate is a local historian and one of the prime movers of the naissant Jewish community in Palermo.

2 Judith Roumani is the editor of Sephardic Horizons. With many thanks to Judith Cohen for help in facilitating this interview.

3 The historical facts and numbers do not by any means allow us to glimpse the sufferings involved, whether for those who uprooted themselves, sometimes for a life of wandering, or for those who stayed and became subject to persecution by the inquisition. Until today the Sephardic kinot of Tisha B’Av lament not only the destruction of the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem, but also Gerush Sefarad, the expulsions.

4 Apparently, according to a published article, the community has been offered an unused Baroque oratory by the local bishop, but it needs substantial renovation. See Julie Carbonara, The Jewish Chronicle “Palermo synagogue set to return after 500 years,” (Oct. 26, 2017). See also the interview with Judith Cohen on Radio Sefarad.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800