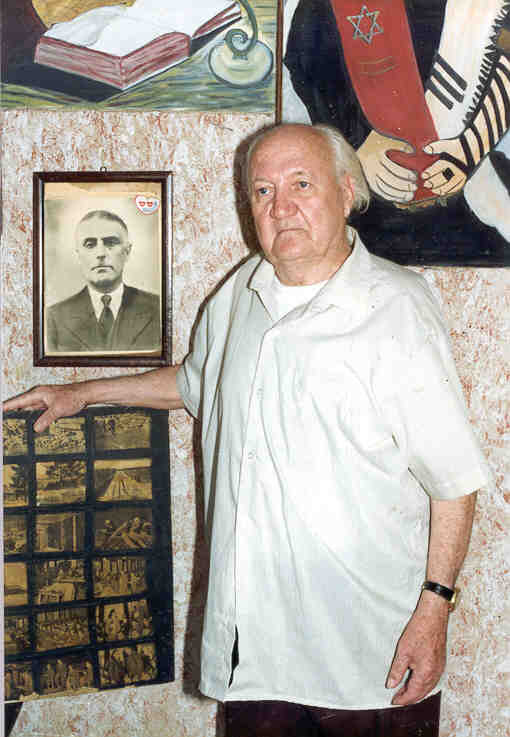

Alberto Sarfati, ‘The Painter’

By Isaac Jack Lévy*

Photography by Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt

Sarfati in his home, 1990

In 1990 my wife Professor Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt and I embarked on fieldwork for a project focused on the domesticated religion of the Sephardim that yielded Ritual Medical Lore of the Sephardic Women: Sweetening the Spirits and Healing the Sick. During the course of our travels, I spoke with many Sephardim about memories of their childhood, of their mothers and grandmothers and what they did to keep the family safe from the ever-present ‘los buenos de mozotros’, (the good among us/the evil spirits). At the same time, I was searching for Sephardi painters of the Holocaust. For the latter project, I visited Sephardic centers in Amsterdam, Athens, Atlanta, Belgrade, Los Angeles, Montreal, New York, Paris, Sarajevo, and museums such as the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, Lohamei HaGetaot in Nahariya, and the Association of Survivors of Concentration Camps (Club de los reskatados de los kampos de konsentrasion) on 68, Levinsky Street, in Tel Aviv. The search was like a puzzle, one locale or individual took us to another, until I had interviewed fifteen Sephardic artists in Israel, Europe, North America, and Turkey who were eager to contribute to my project, The Sephardic Artists of the Holocaust. Some of the artists I interviewed were renowned for their artistic creation, yet none of them were identified in published works as Sephardi.

From April to August, 1990, Rosemary and I carried out research in Israel. We had the opportunity to meet again with Professor Shmuel Refael, the Director of the Salti Institute for Ladino Studies, who told us about Alberto Sarfati, Auschwitz survivor 117425, a resident of Tel Aviv. On January 18, 1985, Refael had recorded in Hebrew a testimony by Sarfati. In the mid-1990s, he provided me a copy of the testimony. In February 2018 when Refael visited us in Dahlonega, Georgia, we discussed Alberto’s statement which appeared in Routes of Hell: Greek Jewry in the Holocaust, Testimonies, edited by him in 1988.

When we were in Tel Aviv in 1990, I was informed by a member of the Greek community that Alberto was in a state of “mental instability” and that I had to be careful in meeting him. I went to see him first alone on June 24, 1990.1 The apartment was in a poor section of the city. He lived on the second floor and the entrance was dark and eerie. I knocked at the door and a female in a gruff voice asked in Hebrew "?מי זה" (Who is it?). The woman even though she had not been in a camp was reluctant to open the door to a stranger, an understandable caution from her years living among survivors and with a husband who experienced insecurity and agony in Nazi concentration camps. I spoke to her in Judeo-Spanish, our shared native language, and told her that I was born in Rhodes and that my parents were from Turkey. Hesitant, she took a minute or so to remove a one-by-two board that secured the door. Once I was in the apartment, Rebecca was gracious and invited me to take a seat. I told her the reason for my visit and asked permission to talk to Alberto who at the time was taking a nap on a sofa. Rebecca offered me a cup of coffee that I politely declined. While we waited for Alberto to wake up, Rebecca allowed me to walk through the apartment. Even though it was somewhat dark, I was able to see that the walls were covered with Alberto’s paintings.

In about twenty minutes Alberto woke up. Seeing me, he asked his wife, “Ken es esti djoven?” (Who is this young man?). Rebecca replied, “Es uno de los mueztros ke vino avlar kon ti” (He is one of ours [Spanish Jew] who came to talk to you). I introduced myself. Alberto was not the “unstable person” that I was warned about. He was instead a dear and friendly man. There was an immediate attachment between us. He embraced me and referred to me as ijo, son, a term of endearment used by the Sephardim towards a younger person.

We moved to the kitchen. Rebecca insisted that I have a cup of coffee and a biskochiko (a ring-shaped cookie) with Alberto. He asked me, “De andi vienes?” (Where are you from?) They asked me about my family. I told them that my family was from Turkey and that during the Italian administration of the Dodecanese Islands they moved to Rhodes where my parents met and married. I spoke briefly about the Sephardic community and my relatives and how we had to leave the island in 1938 as ordered by the Italian government and to take refuge in the international city of Tangiers, Morocco. My mother, grandmother, and I left Tangiers in December 1944 to immigrate to the United States, where we arrived through the port of New Orleans in February 1945, while the war was still going on. I told Alberto and Rebecca about the many relatives we lost in the concentration camps at the hands of the Nazis. They asked me a few questions concerning my time in Tangiers, and how we managed to survive. My answer was that our life was difficult and that we were supported by one of my great-uncles who lived in the United States and by the American Joint Distribution Committee. I stated the obvious, that in spite of our challenges, our life had not been as harsh and precarious as the lives of those who experienced the hellish camps.2

I apologized to Alberto for making him recall the past and asked him if he could tell me of his experiences in the camp and following the liberation. I realized that many years had passed. I was astonished by his comment, “Tengo el tino muy fino para arekodrarme de akeyos dias” (I have a very fine memory to remember those days). Indeed, if Alberto might not have been keenly aware of the present, he said, “El pasado aze parte de mi. Esto no se puede olvidar” (The past is part of me. This cannot be forgotten).

Alberto told me of his birth in Buenos Aires on October 28, 1913 (d. 1998), of his mother Senyora (née Kabali) who also was born in the Argentinian capital and of her premature death. I could tell that his memories were somewhat blurry. Briefly he made reference to his father Moshon who was born in Turkey and their relocation to Salonika. About his life in Argentina, he had told Refael, “I almost remember nothing from my childhood in Argentina” (Refael 2018). When I asked Refael if Alberto had any siblings from Moshon’s first marriage, he responded by email in 2018, “He had a sister from his father’s first marriage,” but no name was given.

In Salonika, Alberto attended a French elementary school but as he expressed it, “I didn’t learn too much. It only satisfied my basic need of learning how to read and write in the French language” (Refael 1988, 424). Life was not easy for them. “Alberto had to take odd jobs in order to financially defray the needs of the house” (Refael 1988, 424). “It was difficult for my father to take care of the house, his work, and watch after me.” So, he took a wife “because he felt that he should find a proper woman that would help him take care of our family” (Refael 1988, 424). From this second marriage Moshon had three children. However, according to Refael’s e-mail of 2018, Moshon had two male and two female children. In either case, no mention was made of their names.

Circa 1930, Alberto considered himself an adult and decided to get married. While still very young he became the father of three children. According to information that Alberto gave to Refael their names were Senyora, Mazaltov, and Moshe. However, in our interview in Tel Aviv Alberto named his three children as: Moshe, Suzy, and Mati.

Existence during the German occupation was horrible. Alberto could hardly describe the attitude of the Germans toward his people:

I was one of the first ones to be transported from Salonika to Auschwitz. It was in 1943, Passover day. The journey was terrible and the arrival indescribable. After going through the required registration, disinfection, [and] haircut, they gave me a new name, number 117425 tattooed on my arm, my new name that I had to remember as long as the Germans controlled my life. I shall never forget number 117425 as long as I live. Since I was strong the Germans sent me to Buna/Monowitz to work on the canal system. There I lived with Greek Jews and Ashkenazim. I was also in charge of a barrack. My job was to ensure that the barrack was clean.

The news of what had happened to his family was devastating: his wife, his three children, sister, sister-in-law, and father were sacrificed in the hell of Auschwitz. All the members of his step-mother’s family also were killed. Dejected he added, “I lost everyone except a female cousin and three male cousins who survived.” “Solo mi padre de 40 anyos i mi madre de 28 se salvaron porke ya estavan muertos de antes” (Only my father who was 40 years old and my mother 28 were saved because they died before). This was a blessing. Other survivors had told Rosemary and me: “Those who died before the transports were the lucky ones, they did not agonize in the trains, in the camps, nor were they gassed or cremated.”

From his interview, Shmuel Refael quoted Alberto, “I worked very hard, I was not lazy. I had the hope that one day I would survive. I knew already that my family had been exterminated . . . . The key word that saved my life was work. The rules were very simple. If you work, you’ll survive” (Refael 1988, 425-26). Alberto later told Rosemary and me that “Los alemanes me kerian bien porke yo lavorava kon voluntad i tenia ekperiensa” (The Germans liked me because I worked with resolve and had some experience). In spite of his hard work, he was not spared from being mistreated, “Haftunas, haftunas” (Beatings, beatings). “Once the Germans beat me on the behind for no reason.” I asked Alberto if he underwent any other punishment:

Not as bad as the 25 lashes. But I can tell you that life in the camp was horrifying. Thousands of people were gassed, hundreds hanged, others were forced to work like animals, worse than animals. No one could survive such atrocities. No matter what we did, we could not satisfy these beasts. Abusing us was part of their essence. No matter who, men, women, children, we were considered expendable. For them, it was more than punishment, it was a game. You see, they enjoyed it at our expense.

As he explained to Refael in 1988, he never forgot this experience, “I can only remember my screams. They really destroyed me with the beating. Even today I am an invalid because of the 25 lashes that I received in the camp. That’s why my back is broken. I was a young boy. I was strong. But everything had been destroyed. I became a lonely man. I’ve lost myself during the Holocaust” (Refael 1988, 426).

At this point Alberto tried to tell us something but hesitated. I asked him if it dealt with some kind of punishment. His answer was, “No, even worse. You see when we were getting off the wagon, from the arriving trains, a German hit me and grabbed my child Suzy away. There was a lot that I cannot forget, but this was special, it was my own child. How can I erase it from my mind?” Alberto always regretted not having killed the German even if it would have cost his life.

Alberto was restless. I realized that it was time to have a break. I turned to Rebecca, who was present throughout the session, for information concerning the family and life in general in Israel. Her comments were: “We have a good family, children, grandchildren, and friends. Over here [in Israel] we are safe, but life is difficult. Our needs are more than we can afford. But Baruh Ashem, we managed, it could be worse.”

As time passed, Alberto was eager to continue where he had stopped: “Thinking all this put me in a state of nervousness, a state that even after the liberation continues to overpower me. I relive the miseries of the camp. As I have declared many times, ‘they are always in front of my eyes, I cannot wipe them out.’”

Komo se puede olvidar? Vide matar a muchos por pasar la ora. Vide ke algunos se rovavan un pedasiko de pan, los entregavan i los alemanes los aharvavan, matavan, los enkolgavan. A vezes el aleman echava el chapeo enbasho i demandava a uno ke se lo truchera. A akeya persona lo matavan sin kulpa i sin razon. Si uno se meneava en el rango por nada, “pop” lo matavan delantre de los ojos.

(How can it be forgotten? I have seen many being killed by the Germans so they could have fun. I have seen some steal a piece of bread, they were turned over and the Germans whipped them, killed them, hung them. Sometimes the German threw his hat down and asked someone to bring it to him. That person was killed without any guilt or cause. If someone standing in line just moved, “pop” [he was shot, right between the eyes].)

Alberto noticed that I was attentive to what he was saying and that I was taking copious notes. He halted his narration and blessed me: “Ke no mos mankes, ke mos bivas i tengas salud i reushita buena” (May you always be among us, may you live and be healthy, and have good success). Then he shifted back to his own experiences. In 1945 as the Russian troops were advancing, Alberto and thousands of his fellow inmates were forced to march, to walk or were loaded on open trains bound for Eastern Europe. It was the Death March. Thousands of inmates were tired, unable to walk, tried to rest on the freezing ground, or just gave up. “The German guards did not miss a chance to stop their misery by killing them,” Alberto told me. He also commented on his struggle to reach his native Salonika:

After quite a long march and excruciating pain I found myself in Bergen-Belsen. When I was liberated I moved like many other prisoners all over burning Europe. It took me quite a long journey to go back to Salonika. And there what did I find? Nothing. Nothing remained from my family, from my childhood and adolescence. Meanwhile I was informed [as he already had suspected in the camp] that my wife had been exterminated. Also, my three small children. I became a troubled person, a lonely one. I knew that the only solution I had was to go to Eretz Israel. (Refael 1988, 429)

While in Salonika, he and Sadi Pichon, also a survivor, opened a store selling halva, cans of cheese, and other foodstuffs. “I was always busy in Greece. I did not like to take walks. I loved my job. I kept the store for 2 or 3 years.” Demoralized, in 1947 he moved to Tel Aviv. Still Alberto’s agonizing memories were his constant companion. “Don’t think that the past did not torment me,” he told me. “I could not forget the tragedies committed by the Germans in the camps—the hangings, murders, whippings, and the crematoria always burning.”

In 1949 he married Rebecca Lahana, originally from Izmir, Turkey. Life was harsh, “I had to struggle to make a living. Still, ‘De kazado empesi a bivir, mas energitiko. Lo mizmo kuando me nasieron los ijos—Moshe, Refael (Rafi) and Lea. Tambien keria a los inyetos, ma kon eyos no fui muy atado porke otra vez me kayo la kayades’” (As a married man, I begun to live, more energetic. Also, when my children were born: Moshe, Refael (Rafi) and Lea. I also loved my grandchildren, but I was not too attached to them because silence overpowered me). Rebecca added: “However until the children grew, he made an effort to spend some time with them. He took them out for walks, to the shore.”

With his skill as a cook, Alberto opened a restaurant, the “Sigma,” on Petah Tikva Street in Tel Aviv. As Refael recounted in February, 2018 during his visit to Dahlonega, Georgia, “It was a Greek-style restaurant. Inside the restaurant he painted all the walls with Greek motifs. The colors were green and blue. And there was a painting of the sea and of the White Tower of Salonika.” Due to his heavy schedule in the restaurant and discord with some members of the club, he and a few of his friends left the association. They, however, continued meeting in Alberto’s restaurant.

Looking for some respite from the haunting memories of Auschwitz, Alberto visited Salonika twice, one of which was in 1970 with his son Moshe. “But I could not stay too long ‘por estar todo triste i aver perdido la kaza, la famiya i los amigos’” (since everything was depressing and for having lost the house, the family and my friends). The second time I went alone. “I intended to stay one month but did not stay more than eight days; whatever I saw demoralized me. It was not the same Salonika. I lost my airplane ticket and returned to Israel by boat.”

In 1958, Alberto decided to go to a health center. The doctors found him extremely nervous and 51% disabled due the beating and a fall in the camp which damaged his back. The State of Israel as well as Germany granted him some indemnity. One of the doctors instructed him to return to the clinic every month even though he knew that it would be difficult for Alberto to do so since he had a job and a new family. “Ma los iniervos dainda estavan ensima, no me deshavan. Al kontrario me aharvavan mas” (The nerves still stayed with me, they did not leave me. On the contrary, they tormented me more). “The doctor then advised me to take up a hobby or to see funny movies in order to relax (to loosen my pain). More crucial, he instructed me to forget some of the past, Something I could never do.) Following the doctor’s advice, I chose to paint, something I liked to do since my early years.”

On June 25, 1990, I visited the Greek Club for Survivors at 68 Levinsky Street. Yakov Razon, a Greek boxer who had survived the Holocaust, told me:

In 1951 Alberto and a few survivors—Pepo (Yosef) Kalamaro, Morris Mosche, Elia Tevas, Amariyo Shelomo, and Mordehay Sarfati, an honorary member—founded the Asosiasion de los Reskatados de los kampos de Konsentrasion (Association of [Greek] Survivors of the Concentration Camps). Some told me that Alberto was the first President and held the position 4 or 5 years. While others stated that he held it only one year.

Alberto told Refael that the purpose of the club was to gain “recognition of the Israeli society. We wanted very much that someone would acknowledge our suffering” (Refael 1988, 429). Razon recounted to me, “He was energetic, a hard worker, quite capable to run the organization. He was kind and did everything to assist the members. However, since 1968, Alberto’s health had continued to decline. He sold his restaurant and confined himself at home.” Several of his friends visited him and tried to lift his spirits, but Alberto rejected their efforts. They finally realized that he preferred to paint alone and in silence. It was then that his friends gave Alberto the moniker ‘the painter’. “Little by little they stopped coming, many died, and others left town.” Alberto added, “It was then that I stopped going out. I did not care for the movies, the theatre, for nothing, only to stay home and paint. I started smoking two or three packs of cigarettes a day, just to keep busy.”

While talking with Alberto, I mentioned the conversation I had had with Razon. Rebecca agreed that there was a change in Alberto’s attitude, “He was not the same man. I could tell the difference in his behavior and interests.” Still, she defended her husband, “Aunke las sirkuntansias lo trokaron, Alberto era buen padre, buen marido, Baruh Ashem. No era bividor. Fue bueno kon la famiya. Era siempre azedor de buendades para todos. Era komo un padre para los ke venian” (Even though circumstances changed him, Alberto was a good father, a good husband, thank God. He was not a drinker. He was good with the family. He always did good deeds to everyone. He was like a father to all who came [to visit us]).

Alberto returned to his narration:

I continued working in the restaurant. In June 1967, when the Six-Day War started, after returning home at night, I painted. I began to draw with pencils with the children. In 1968 I started to paint with colors. I learned to paint by myself. I was an amateur. First, I copied post cards, then from books. Originally, I copied small pictures and I enlarged them. If something was not to my liking, I changed it in order to improve it. I did all this up to a few years ago. However, “En cuanto a lo del kampo, lo de la Shoah, todo era de mi kavesa, todo lo eskoji yo de lo ke me akodrava, de lo ke pasi. Todo kaji gris, flamas, etc.’” (In so far as the material of the camp, of the Catastrophe [Holocaust], it is all from my head. I selected everything from what I remembered, from what I endured. Everything was almost gray [gloomy], flames, etc.).

I asked Alberto what effect painting had on him. “It relaxed me. It liberated me. It cleared my head. It was an escape at least for a few hours. The doctor in the clinic was right, “painting was a big solution to my problems. Moreover, it gave me a chance to give visual testimony of the Holocaust, of the hardships of our brothers and sisters of Greece, a fact that no one seems to know.” In his response to Refael, he was more loquacious:

In my apartment in the center of Tel Aviv, I have a special room [and a corridor adorning the walls] which [are] full with oil paintings, all of them dedicated to the Holocaust. Each of them tells a specific story regarding my personal life in the camp. That is the reason I would like to show the readers all of my paintings and through them narrate the horror story of the Greek Jews in the Holocaust. Through the paintings I can show the deportation to the camps, trains full of anguished people and full of skeletons . . . . I can remember quite well the barracks full of people, around 2,000 pushed into each block. They were tired, exhausted, thrown on each other’s shoulders. (Refael 1988, 424)

Alberto stated that he gave some of his art to organizations, in particular three to a “Deaf and Dumb Society,” several to the B’nai B’rith, and ten to the Israel Defense Forces. “These are sold by them to raise money. I never charge anyone.”

When I inquired what happened to Alberto’s art after his death, Refael e-mailed me the following message, “Only God knows where it is now. I spoke to his son Raphael who told me that after the death of his father, the family donated everything to a school in Raanana or in Kfar Sava, and it cannot be located now. To the best of my knowledge it was thrown away. What a barbarity.”

Through his designs and paintings, Alberto left us a visual legacy of the tragedy that befell his people. Following are some of the photographs taken by Rosemary of the oil paintings and sketches adorning the walls of Alberto’s home. As he reported to Shmuel, “Each one of them tells a specific story regarding my personal life during the time in the camp . . . . Through them I narrate the horror story of the Greek Jews in the Holocaust.”

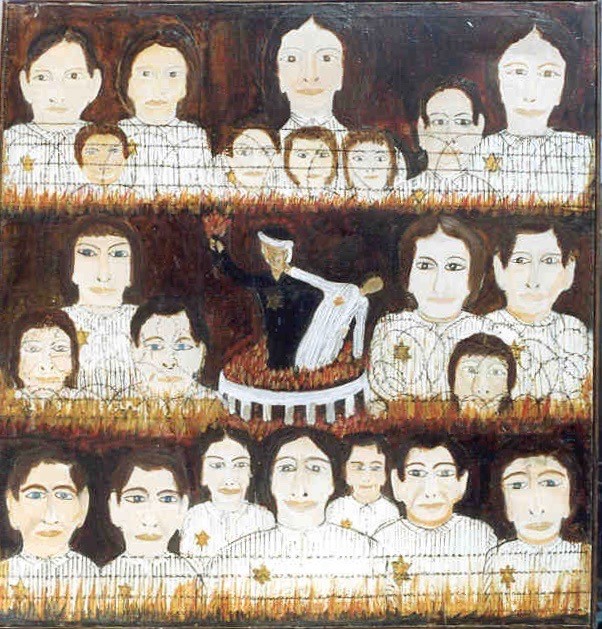

The Deportation: Alberto’s family. Center, “How they took us to the ovens.”

“La entrada” (The Arrival): When the inmates arrived in the camp.

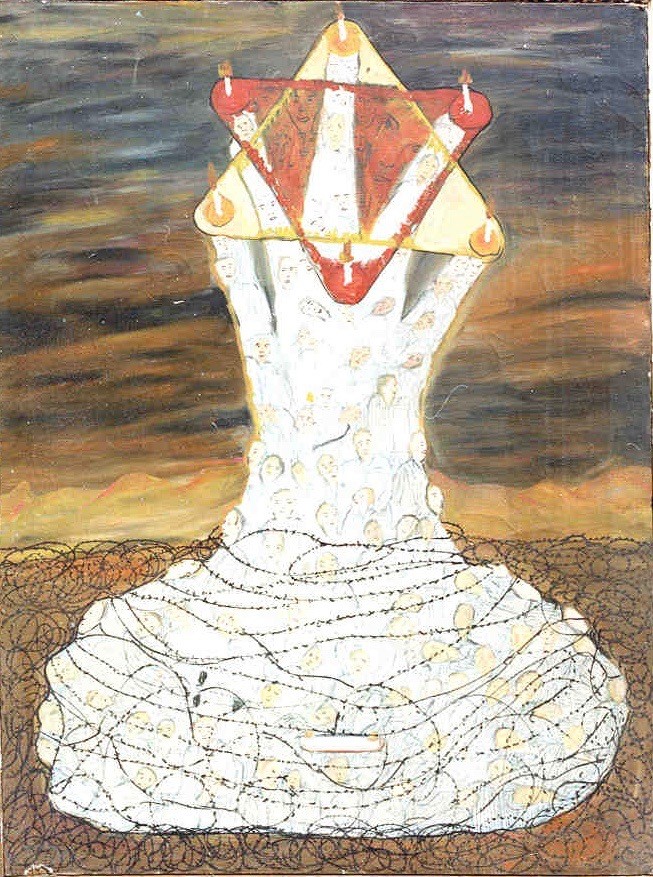

Center: Emblem of the block, Magen David

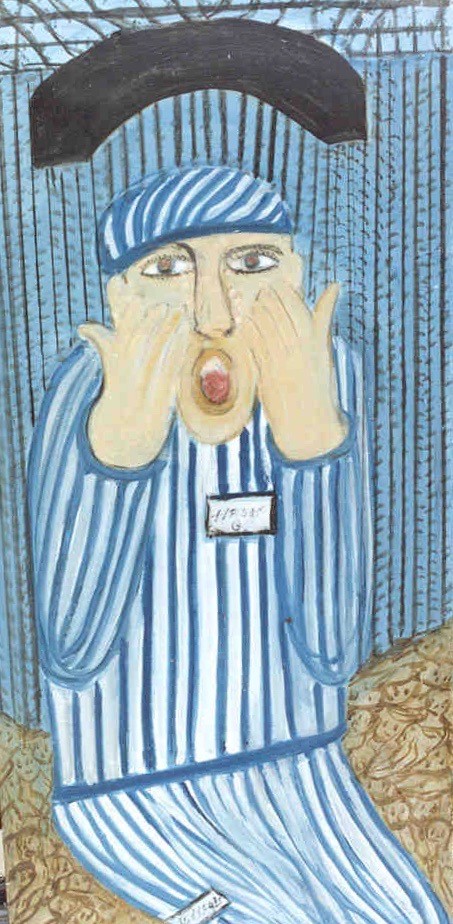

Self-portrait of Alberto,

holding the Magen David

and standing on the serpent, the sign of death.

“Espanto” (Shock)

Self-portrait in camp, No. 117425

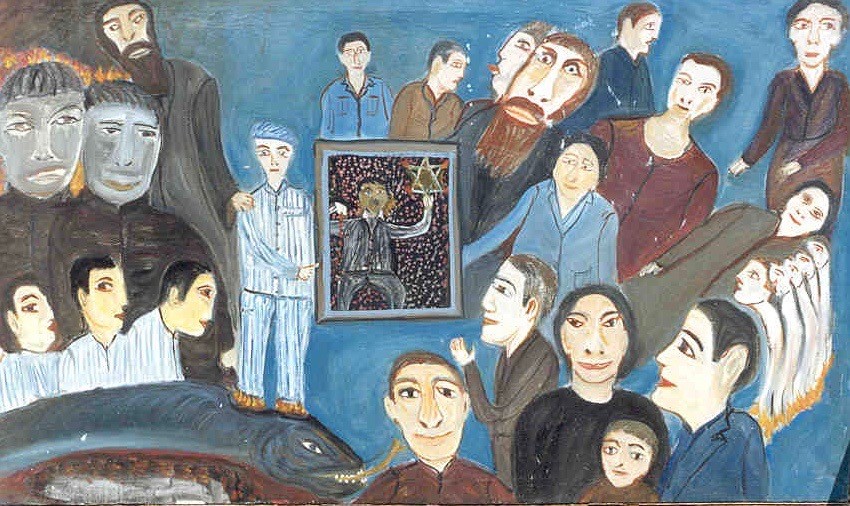

Destruction of the Jews in the camp and their ascension into heaven.

“El Krematorio” (Crematorium)

The buildings show the gathering of the cities and villages of the Jews; the burning torch shows the chimney spewing the souls of the massacred Jews ascending to heaven; the face of the beast shows the inmates he has devoured; the Hasid holding his bundle on his shoulder represents the wandering Jew; the river of fire surging toward him is consuming the Jews.

* Isaac Jack Lévy (M.A. Iowa, 1959; Ph.D. University of Michigan, 1966) is Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Spanish Language and Literatures at the University of South Carolina. He is author of And the World Stood Silent: Sephardic Poetry of the Holocaust; Jewish Rhodes, A Lost Culture; and co-author with Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt of Ritual Medical Lore of Sephardic Women: Sweetening the Spirits, Healing the Sick. Spanish is rendered in Judeo-Spanish orthography, which differs from that of modern Spanish.

1 I interviewed Alberto Sarfati in Tel Aviv, Israel on June 24 and 25, 1990. On the 24th I saw him alone and on the 25th with my wife Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt.

2 For an account of my family’s journey from Rhodes to Tangiers to the United States, see Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt, “Stories, Food, and Place: Following a Sephardic Family to a New Home,” Sephardic Horizons, Winter 2016, http://www.sephardichorizons.org/Volume6/Issue1/Zumwalt.html

References Cited

Refael, Shmeul. 1988. “Sarfati, Alberto.” In Routes of Hell, Greek Jewry in the Holocaust. Testimonies, edited by Shmeul Refael, 423-31. Tel Aviv: The Institute for the Research of Salonikan Jewry and The Organization of Greek Death Camp Survivors in Israel. In Hebrew.