Today's Ortaköy in İstabul's Beşiktaş district. Neighborhood where the Nasi's Belvedere Mansion (from the Italian: fair view) must have been located.

Belvedere and Kuru Tsheshme: Sephardic Printing in Late Sixteenth Century

Constantinople

By Marvin J. Heller *

Hebrew printing in Constantinople (Hebrew, Kushta, Istanbul) has a long and proud history. The first press there, indeed, the first press in any language in the Ottoman Empire, was founded by David and Samuel ibn Nahmias, refugee brothers, from Portugal. The first title printed was R. Jacob ben Asher’s Arba’ah Turim (1493), followed by a Torah, Haftarot, Hamesh Megilot with commentaries, and Megilat Antiochus more than a decade later in 1505.1 As many as 320 Hebrew titles were published in Constantinople in the sixteenth century.2 The press of Doña Reyna (d. c. 1599), the daughter of the famous Doña Gracia (Beatrice de Luna, c. 1510–1569) and the wife of Don Joseph Nasi, (c. 1524–1579), Duke of Naxos, the last to operate there in the sixteenth century, is the subject of this article.

With the death of Solomon Jabez in 1593, Constantinople was left without a Hebrew press. The void was filled by a remarkable woman, Doña Reyna, scion of an important and wealthy Sephardic family that had been living as Crypto-Jews, first in Lisbon and afterwards in Antwerp. When the hand of the beautiful Doña Reyna was solicited for a Christian noble by Queen Mary of Hungary, Regent of the Netherlands, and the sister of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, her mother, Doña Gracia, reputedly responded that she would rather see her daughter dead. As a result, the family fled to Constantinople in approximately 1544. Indeed, Doña Gracia was imprisoned in Venice for Judaizing, and was only released after the Turkish Sultan intervened on her behalf.3

In Constantinople, Doña Reyna openly returned to Judaism and married her cousin Don Joseph Nasi, influential at the court of Sultan Selim the Ottoman Emperor. Don Joseph's influence waned rapidly under Selim’s successor, Murad, who became Sultan in 1574. Murad confiscated most of Don Joseph's estate after the latter’s death, leaving Doña Reyna with only her dowry of 90,000 golden ducats. Cecil Roth suggests that Doña Reyna was “not by any means in reduced circumstances” as she had presumably inherited her mother’s vast fortune.4

Doña Reyna occupied herself with charitable works; she supported a yeshiva and scribes who transcribed Hebrew books. She established her own press at her residence, the palace of Belvedere on the eastern shore of the Bosporus in 1592. After a hiatus in the press’s operations from c. 1595 to 1597, it was relocated to Kuru Tsheshme on the European side of the Bosporus. Doña Reyna’s intent in opening the press was certainly not to engage in business and make a profit, but rather to support Jewish scholars in Turkey and Eretz Israel. With these efforts, she followed in the footsteps of her mother and her husband, who had assisted many scholars to print their books at the Jabez press.5

Doña Reyna appointed R. Joseph ben Isaac Ashkeloni to manage the press. Approximately seven titles were published in Belvedere and ten in Kuru Tsheshme, the number varies somewhat according to different sources, until 1599, when the press ceased publishing, possibly due to Doña Reyna’s death. This article briefly describes the works printed in Belvedere and Kuru Tsheshme, and highlights several examples in greater detail.

Books Printed at Belvedere

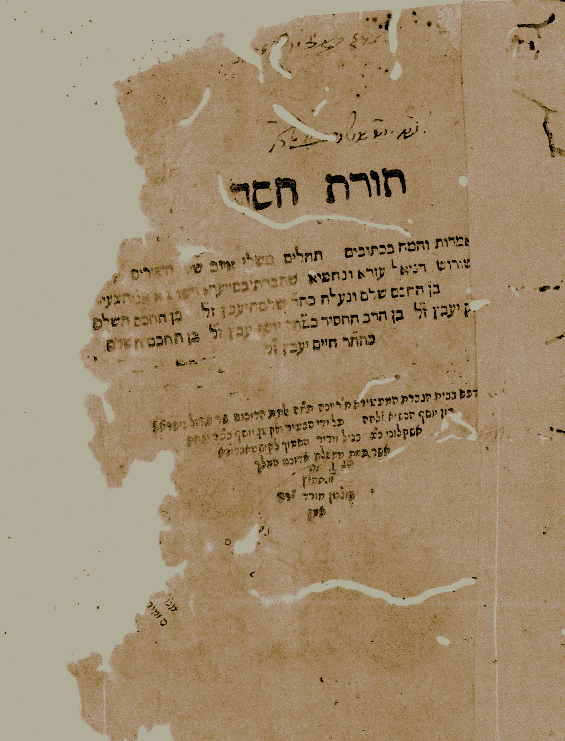

Torat Hesed R. Isaac Jabez Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak.

Torat Hesed R. Isaac Jabez. Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak.

The books printed at Belvedere are relatively small, their title-pages unadorned, their text relatively concise. The first works are Yafik Razon, R. Isaac Jabez’s commentary on the haftarot, completed on 13 Tamuz 353 (13 July, 1593) and Torat Hesed on Hagiographa. The books that followed between 1593-95 are undated, and consist of Libro Intitolado Yichus ha‑Zaddikim, a guide book to Eretz Israel, and the press’ only Ladino title; Sefer Gal shel Egozim, derashot by R. Menahem ben Moses Egozi, on the book of Genesis; Siddur Tefilot he-Hadesh, a prayer book with the commentary Zevah Elokim by R. Meir ben Abraham Angel of Belgrade; Keshet Nehushah, Angel’s ethical work in rhymed prose; and Torat Moshe on Genesis, the first part of R. Moses ben Hayyim Alshekh’s (Alshekh ha-Kodesh, d.c. 1593) Torah commentary.

Yafik Razon and Torat Ḥesed are both rather small works by R. Isaac Jabez, son of the Constantinople printer Solomon Jabez. The title-page describes Yafik Razon, a quarto (40: [2], 57, [1] ff.), as “a commentary on the haftaroth according to the custom of the Sephardim and the Ashkenazim; it is a portion of Torat Hesed written by the young Isaac Jabez.” Torat Ḥesed, in contrast is a folio (20: 40, 60 ff.) on Hagiographa, comprised of ten sections on Ketuvim, Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastics, Ahashverot, Daniel, Ezra, and Nehemiah. The title-page proceeds to give Jabez’s genealogy “I am the young Isaac Jabez, son of the complete sage, the illustrious R. Solomon Jabez, son of the complete sage R. Isaac Jabez, son of the pious sage R. Joseph Jabez, son of the complete sage R. Hayyim Jabez” followed by information about the press. In the introduction, the author notes the limited size of the press runs; Yafik Razon was issued in three hundred copies, Torat Hesed, a larger work, in only two hundred copies. The text follows printed in two columns in rabbinic type (Rashi). R. Isaac Jabez also wrote Ḥasdei Avot (Constantinople, 1583) on Avot.

The second Belvedere title, Libro Intitolado Yichus ha‑Zaddikim, the press’ sole Ladino title, is very rare, extant only in a four page octavo (80) pamphlet in a New York library and in two folios in the Mehlman collection. The catalogue entry of the latter notes that no known complete copy exists. Despite the limited number of surviving leaves found in libraries today, Joseph Hacker suggests that the work had been printed in its entirety.6

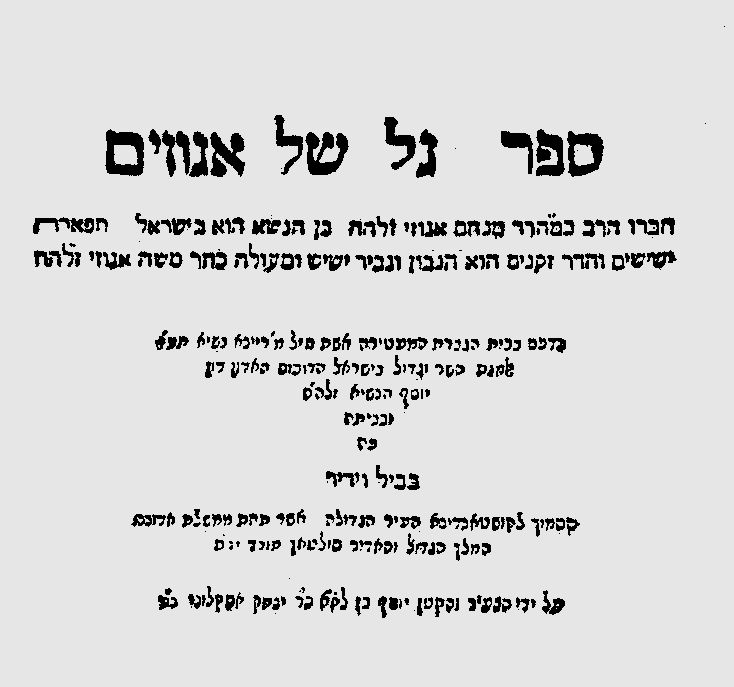

Sefer Gal shel Egozim by R. Menahem ben Moses Egozi (?-1571), a sixteenth century Talmudist, rabbi, preacher, and poet in Constantinople is a small folio in format (20: 53 (should say 61), [1] ff.). This work, described in greater detail below, is discourses on Genesis. This and his other work allude to his name in the title. The title page describes it as in the original and in English translation:

Sefer Gal shel Egozim

Written by ha-Rav (our teacher the honorable Rav and Rabbi) Menahem Egozi (may he be remembered for life everlasting), son of the noble, he is in Israel splendor of the aged and “the glory of the old” (Proverbs 20:29), he is the wise and excellent venerable R. Moses Egozi (May he be remembered for life everlasting).

Sefer Gal shel Egozim, R. Menahem ben Moses Egozi. Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak.

Printed in the house of the royal lady, a woman of valor, (Proverbs 31:10) Reyna Nasi, widow of the Duke, prince and noble in Israel, Don Joseph Nasi (May he be remembered for life everlasting) in her house here Belvedere near the great city of Constantinople, which is in the domain of our lord the king, the great and mighty Sultan, Murad (may his majesty be exalted). By the young and unworthy Joseph son of (my lord and father) R. Isaac Ashkeloni (May his soul be in paradise).

From the phrase after Egozi’s name, “may he be remembered for life everlasting,” it is clear that Gal shel Egozim was published posthumously. The title page is followed by verse written by the author in praise of the work, introductory remarks, and from [4a] onward the text. The text is printed in two columns in rabbinic (Rashi) type, except for headings which are in square letters. It is accompanied by glosses, placed as inserts to the text. In the introduction, Egozi explains the title, writing that in order to speak that which is in his heart he has called this small work Gal shel Egozim, a parable for a pile of stones,

“For every man who wishes to place a pile of large stones, hewn stones, limestone, scattered and gravel, in its completeness, so I stood and went down to the garden of nuts (egozi) in Gan Eden, our holy Torah and the words of our rabbis, and gleaned after the gleaners (Ta’anit 6b, B. M. 21b), nuts large and small.”

The following text, from Rashi quoting Avot de‑Rabbi Nathan ch. 18, is the source of this parable:

“R. Tarfon was like a pile of nuts gal shel egozin ( Gittin 67a), that is, just as one takes from a pile of nuts the remainder fall one on top of the other, so R. Tarfon, when a student came with an inquiry, he responded with proofs from Scripture, Midrash, Mishnah, halakhah, and aggadah, all together”.

This is the sole printing of Gal shel Egozim. Egozi was also the author of Ginnat Egoz, a collection of his correspondence and poetry, extant in manuscript; a responsum in the teshuvot of R. Elijah ibn Hayyim (Constantinople, c. 1603-1617); and verse at the end of She’ilot u’Teshuvot ha-Geonim in praise of that work (Constantinople, 1578).

Two Belvedere titles were written by R. Meir ben Abraham Angel of Belgrade (c. 1564-c. 1647), a renowned preacher and rabbi. Angel was born in Sofia or Salonika but relocated at a young age with his family to Safed, where he studied under R. Samuel ben Isaac Uceda, R. Eleazar Ascari, and R. Hayyim Vital. Angel later returned to Sofia, where he served as rabbi, and afterwards was rabbi in several other communities, among them Belgrade. Angel traveled through Poland, Greece, and Italy, finally returning to Safed, where he died.

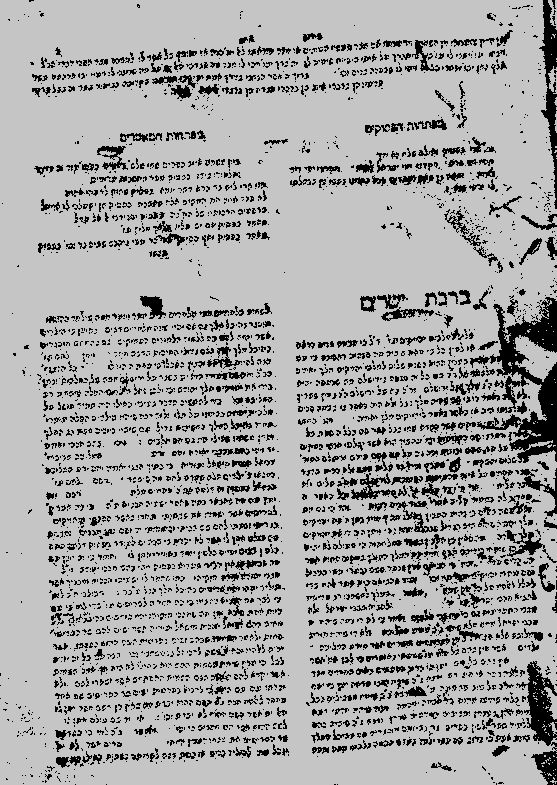

Zevah Elokim, R. Meir ben Abraham Angel. Jewish Theological Seminary.

Angel’s Belvedere titles are Siddur Tefilot he-Hadesh, a prayer book with the commentary Zevah Elokim (120: 83+ ff.) and Keshet Nehushah (40: 16 ff). The title page of the siddur provides basic information about the book and author, and then informs that “when the named author saw the great miracle done in the days of Mattathias ben Johanan, he took it to heart to writeme kamocha for Hanukkah with great care in the style of alpha beta . . .” The text follows, in a single column with square vocalized letters accompanied by the commentary, Zevah Elokim, in rabbinic type (Rashi). That name is from “The sacrifices of God ( Zevah Elokim) are a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise,” (Psalms 51:19). Siddur Tefilot he-Hadesh, includes weekday, Sabbath, Rosh Hodesh, and festival services, as well as prayers for Hanukkah and Purim.7

Keshet Nehushah (c. 1593, 40, 16f.), according to the title page, is written in clear language and holy sweetness. It is an ethical work in which the inclination to do wickedness or to transgress is personified8, resulting in moral conflict. The title Keshet Nehushah (a bow of bronze), is derived from “He teaches my hands to war; and trains my arms to bend a bow of bronze” (Samuel II 22: 35, or similarly Psalms 18: 35). The text, verse alternating with rhymed prose, is in a single column comprised of square vocalized letters and rabbinic type (Rashi). Angel is better known for his sermons, Masoret ha-Berit (Cracow, 1619), 600 homilies based on the Masorah Magna of the Bible, and Masoret ha-Berit ha-Gadol (Mantua, 1622), on 1,650 such readings.

The last Belvedere title is R. Moses ben Hayyim Alshekh’s popular and much republished Torat Moshe (20: 82, [1]) on the book of Genesis. The complete work on the entire Torah was published by Alshekh’s son Hayyim in Venice in 1601. Alshekh was a member of the rabbinical court of R. Joseph Caro (1488-1575), who conferred upon him the full ordination reintroduced by R. Jacob Berab (c. 1474-1546). Torat Moshe is similar in format to the commentaries of Don Isaac Abrabanel (1437–1508) and R. Isaac Arama (c. 1420 – 1494) (Akedat Yizhak), in that each section begins with a series of questions, followed by detailed answers. The substance of Alshekh’s responses are homiletic, stressing the moral-ethical aspect of the Torah, and is based on Talmudic and midrashic sources.

Books Printed at Kuru Tsheshme

After the three year hiatus in Doña Reyna’s operations, the press relocated to Kuru Tsheshme. The reason for this move from Belvedere is unknown, perhaps an outbreak of plague or conflagration in Constantinople, or perhaps Doña Reyna’s reduced circumstances are possibilities. Printing began in Kuru Tsheshme with R. Samuel Uceda’s Iggeret Shemu'el, the first of about ten, primarily small books printed there. Among the other titles issued by the press are part four of the She’elot u’Teshuvot of R. Joseph ibn Lev (Maharival) (c.1505-1580); Toze’ot Hayyim, R. Elijah de Vidas (16th century) abridgement of his Reshit Hokhmah;Tappuhei Zahav on the first Book of Psalms by R. Moses Alshekh; Pizei Ohev, a commentary on Job by R. Israel Najara (c. 1555-c.1625); Minhat Kohen on the Masorah by R. Joseph ben Schneur ha-Kohen; Moshiat El on Hoshanot and hakofot and Ta’am le-Mussaf Takanot Shabbat, both by R. Joseph ben Abraham ha-Kohen; tractate Ketubbot and, according to Ch. B. Friedberg, Pesahim.9

Iggeret Shemu'el, R. Samuel ben Isaac Uceda. Library of the Valmadonna Trust.

Iggeret Shemu’el is R. Samuel ben Isaac Uceda’s (Uzedah) (1540–?), commentary on the book of Ruth. The author, a commentator, preacher, and kabbalist was born in Safed in the first half of the sixteenth century. The surname Uceda is likely derived from the town of that name in the archbishopric of Toledo. A student of R. Isaac Luria (ha-Ari) (1534-72), R. Hayyim Vital (1542-1620), and R. Elisha Gallico (d. c. 1583), Uceda became a rabbi in Safed, establishing a yeshiva in that city at the age of 40. His students included R. Joseph Benveniste and R. Meir Angel.

Iggeret Shemu'el is a small quarto (40: 84 ff.) book. In contrast to the bare title-pages printed in Belvedere, the title-page of Iggeret Shemu'el has a row of florets above the text. It informs that the work is by Uceda and on Ruth, which he had at his right to support and bolster him the commentary of Rashi. It was printed at the press and with the letters of the lady [Doña] Reyna. An introduction from Uceda appears on the verso of the title page, followed by the text. The book of Ruth is in the center of the page in square unvocalized letters, accompanied by the commentaries of Rashi and Uceda.

In the introduction, Uceda notes his activities in Safed, where he spread Torah and preached every Shabbat. Those lectures culminated in his commentary on Avot, entitled Midrash Shemu'el. Another work, Lehem Dimah on Lamentations, deals with the destruction of the Temple. Uceda next remarks on his commentary on Ruth. For forty years he had not once left Safed, but the financial needs of the yeshiva necessitated his traveling to Constantinople to raise funds. There, he found succor for the yeshiva in the philanthropist R. Abraham Algazi (1615—1640). At the time that Iggeret Shemu'el was printed, Uceda was in Constantinople.

Uceda titled the work Iggeret Shemu'el, in accordance with the prophet Samuel, author of Megillat Ruth, who intended that his book be as a letter (iggeret) in the hand of all Israel. The intent of the letter was so that they should know that David was fit to be king. Furthermore, as Uceda remarks, his name is also in this title.

Iggeret Shemu’el , and Midrash Shemu’el, which was sufficiently popular to be published three times in this century (Venice, 1579, 1585, Cracow, 1594), are both noteworthy for Uceda’s use of Sephardic sources from his extensive library. Among them are R. Meir Abulafia, R. Moses Alashkar (1466-1542), R. Solomon Alkabez (ca. 1550), R. Isaac Caro, and R. Samuel ibn Sirilyo. Uceda’s books are also a valuable source about the Safed community and the circle of the Ari. Uceda is known to have written commentaries on all five Megillot, however, only the books on Ruth and Lamentations were printed, while his commentary on Esther remains in manuscript.

She’elot u’Teshuvot (21 cm. 4, [94] ff.) by R. Joseph ibn Lev (Maharival) (c. 1505-1580) is part four of his She’elot u’Teshuvot,.The first part, in which ibn Lev acknowledges “the many favors and acts of kindness done for him by Doña Gracia,” was published in Salonika (c. 1558) by Joseph Jabez. The second and third parts were published in Constantinople by Solomon Jabez and Solomon and Joseph Jabez, respectively (c.1568, 1573). Ibn Lev, a student of R. Joseph Taitazak and a great scholar, is also remembered for his unrelenting defense of the indigent and defenseless, making him enemies among the wealthy. He was appointed to the bet din of Monastir at an early age; however, a dispute forced him to relocate to Salonika in 1534. There, he became involved in a rancorous controversy with R. Solomon ibn Hasson, and afterwards with the tyrannical Baruch of Salonika. Soon after, in 1545, his son David was murdered. Following this, ibn Lev removed to Constantinople in 1550 where he became an instructor in the yeshivah founded by Doña Gracia Nasi.

The title-page informs that this volume also includes a novella on tractates Kiddushin and Avodah Zara and that it was printed “at the behest of the crowned and excellent lady Reyna, widow of the Duke, Prince and Noble in Israel, Don Joseph Nasi of Blessed Memory. . . .” Both the items are set in rabbinic (Rashi) letters.

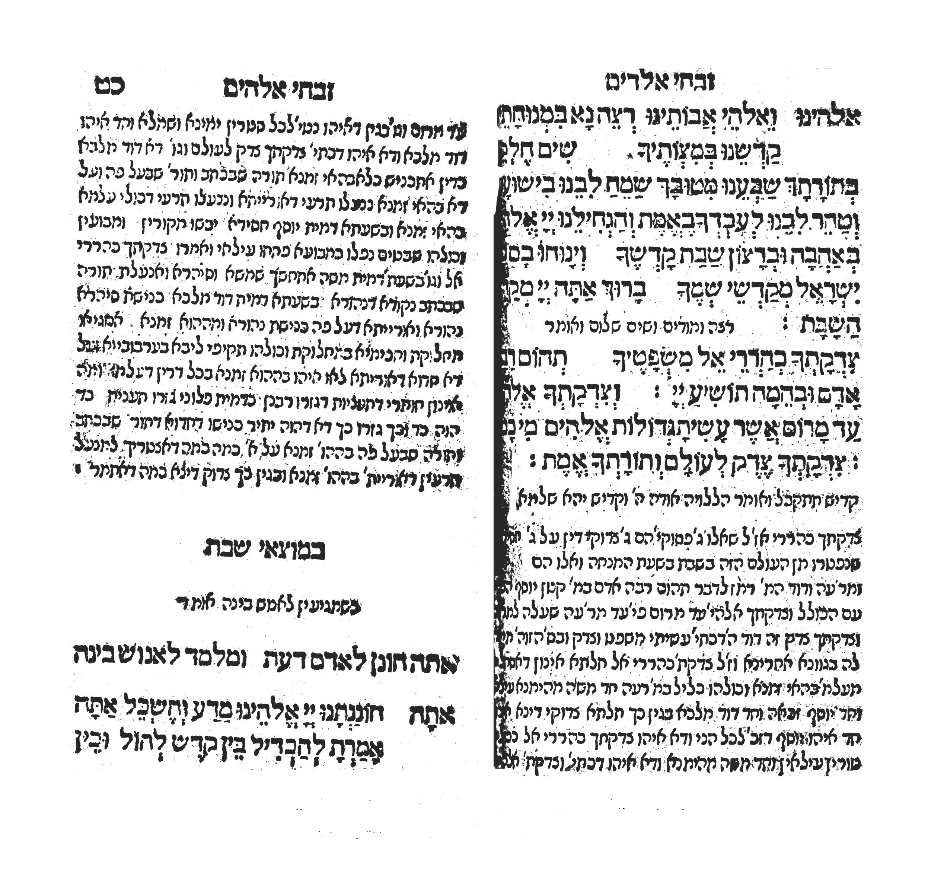

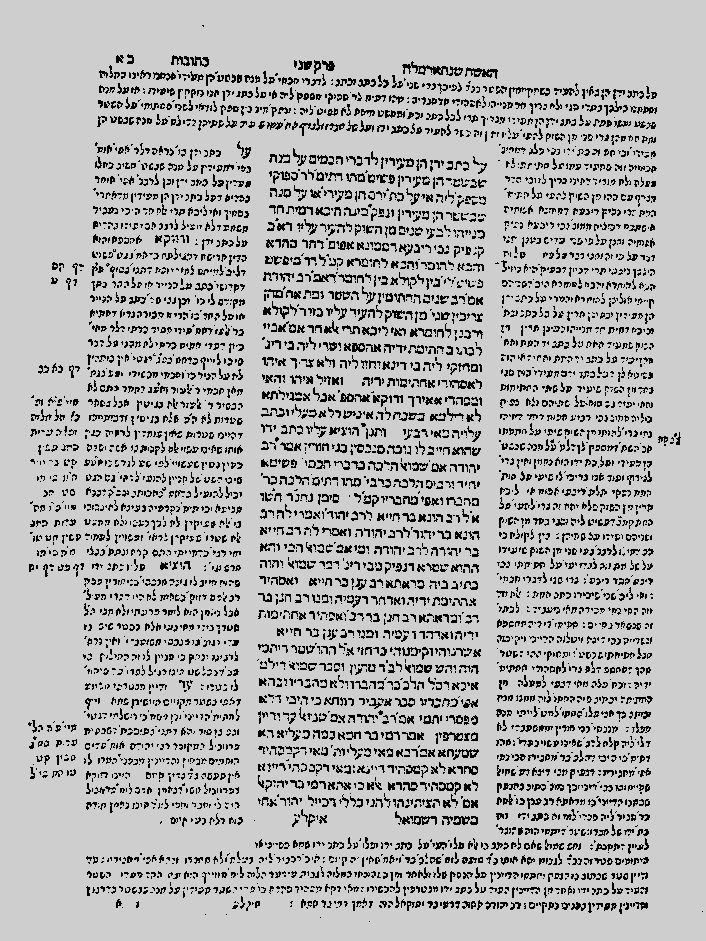

One, perhaps two tractates were published in Kuru Tsheshme including the Tractate Ketubbot. The title-page of Ketubbot, the tractate known with certainty, has a brief text that begins by noting the numerous commentaries printed with and after the tractate. Among them are Rabbenu Asher ben Jehiel (Rosh) (c. 1250-1327) and R. Solomon Luria (Maharshal) (1510-73). Raphael Nathan Nata Rabbinovicz quotes R. Moses ben Mahrasdam in a responsum that the paper and the workers came from Venice. It is Rabbinovicz’ opinion that the presswork is poor, inferior, and blurry. Rabbinovicz, however, did not see the original title page, but relied on a transcript prepared for him by Dr. Friedlander of the British Museum (now the British Library). It is not clear, therefore, whether the copy Rabbinovicz saw only lacked a title page or whether he relied on Dr. Friedlander for a full description of the tractate.10 The reader, however, can look at an amud (page) below (also from the British Library) and see if he/she concurs with Rabbinovicz as to the quality of the presswork.

Tractate Ketubbot British Library.

Tractate Ketubbot British Library.

In the colophon, Ashkeloni, who managed the press, explains his intent in publishing the tractate, “From the day that I began to take control of the indomitable press to be of those who benefit the multitude, and in which my soul should be preserved, my spirit and my soul has desired and longed for the good that all desire; that is, to print a few of the tractates that the students generally learn. I began with this tractate to merit those who understand as well as the student.”

Despite Ashkeloni’s intent to include the Rosh and Maharshal in the Ketubbot, neither were printed. This may be attributed to financial restraints on publishing the work. Doña Reyna was the sponsor of the press as mentioned on the title-page, yet her finances were not unlimited, especially as Sultan Murad had confiscated most of Don Joseph's estate in 1579, thus making additional financing necessary. Therefore as explained in the colophon, the method used by Ashkeloni to finance publication of Ketubbot, was one employed previously by the Jabez brothers to defray the considerable cost of their edition of the Talmud (1583-95). This unusual means of financing a Talmud edition was one apparently utilized only in Constantinople. The Talmud was published in sections or pamphlets in return for partial payments and distributed weekly on Shabbat. Subscribers, who paid each week, obligated themselves to acquire all of the sections, that is, the complete edition. The purchasers received sections as they were printed, paying at intervals for what they had received. In the colophon, Ashkeloni continues to explain how he hoped to finance the tractate and the omission of the Rosh and Maharshal, writing that he,

“… thought to easily collect considerable sums, from noble‑minded individuals, from Shabbat to Shabbat, the amount to print at regular intervals, the expenses of the press. They would be prepared [for this] as they are concerned with the work, with acquiring paper and additional requirements, so that the desire of HaShem will succeed until its completion. . . .

I was unable to print Rabbenu Asher because a handful cannot satisfy a lion and the means were insufficient, and also [the commentary of] R. Solomon Luria is still not available to me. If HaShem will permit and I have the means, I will . . . print Rabbenu Asher and [the commentary of] R. Solomon Luria. . . .”

The second tractate attributed to the press in Kuru Tsheshme, Tractate Pesahim, has been questioned, and, indeed, is a matter of dispute among bibliographers. Rabbinovicz assumes that since Ashkeloni was unable to print the Rosh, he didn't print any other tractates afterwards. He suggests, however, that “it is also possible that he had previously printed many treatises before [Ketubbot.]”11 As noted above, Friedberg includes Pesahim, among the titles printed at Kuru Tsheshme. While some disagree, there appears to be evidence confirming that this edition was indeed printed. Israel Mehlman writes that, “This tractate, however, was printed, and Raphael Nuta Rabbinovicz offered it for sale, incomplete but with the title page ( Listing of Antique Books, Munich, 1886, no. 4661).” Ephraim Deinard also records this edition in Atikot Yehuda, noting that it is a unique folio copy of the tractate and that this is the only extant copy, but without giving its location.12

The only edition of R. Joseph ben Schneur ha-Kohen’s Minhat Kohen, a small duodecimo (120: [84] ff.) work on the Masorah the correct form of the system of critical notes on the Biblical text, was published at Kuru Tsheshme. The text includes tikkun soferim (scribal emendations), arranged alphabetically and followed by parashah (weekly Torah readings) Completion is dated in the colophon to Friday, 14 Tishrei 5358, “Let Israel rejoice in Him who made him, "ישמח ישראל בעושיו,” (16 September, 1597) (Psalms 149:2).

Toze’ot Hayyim (120: [80] ff.) by R. Elijah de Vidas, a 16th century Safed kabbalist, is often described as an abridgement of de Vidas’ Reshit Hokhmah, a popular ethical work first published in Venice (1579) and reprinted more than fifty times. In contrast to several abridgements of Reshit Hokhmah, Toze’ot Hayyim was written by de Vidas.

Conclusion

The Hebrew presses in Belvedere and Kuru Tsheshme, founded by the noble lady Doña Reyna, were neither long-lived nor did they publish many books. Their value and importance have been questioned and evaluations of the physical quality of the presses’ publications have varied. We have noted Rabbinovicz’s view of Ketubbot as “poor, inferior, and blurry.” Similarly, Cecil Roth, who praises Joseph Nasi’s patronage of Hebrew printing in Constantinople, is much less favorable, indeed quite negative concerning the presses in Belvedere and Kuru Tsheshme. Roth writes that “Asceloni had a penchant for trivialities, and advised his patroness badly,” and criticizes both the quality of and the titles printed in Belvedere, including among his examples Alshekh’s Torat Moshe, a work for which the National Library of Israel catalogue has more than fifty entries.13

Doña Reyna’s press did operate under financial restraints. It is clear from the limited size of press runs, that the press was operated with limited means. For example, Isaac Jabez’s Torat Hesed was issued with two hundred copies and Asceloni’s issue of Ketubbot in subscription. Nevertheless, the press has a number of fine accomplishments to its credit.

It published a wide variety of titles, by both well-known and less well-known, authors, among the former Moses Alshekh and Elijah de Vidas, among the latter Joseph ben Schneur ha-Kohen. Works published include a commentary on the haftaroth (Yafik Razon), commentaries on Genesis (Sefer Gal shel Egozim and Torat Moshe), on Ruth (Iggeret Shemu'el), on Job (Pizei Ohev), and on Psalms (Tappuhei Zahav), liturgy ( Siddur Tefilot he-Hadesh with the commentary Zevah Elokim , Moshiat El on Hoshanot and hakofot and Ta’am le-Mussaf Takanot Shabbat). Other titles include ethical works (Keshet Nehushah, Tappuhei Zahav), on the Massorah (Minhat Kohen), She’elot u’Teshuvot, and at least one Talmudic tractate, as well as a Ladino work ( Libro Intitolado Yichus ha‑Zaddikim). In addition, several of the presses’ publications are the only edition of that work. For example,Gal shel Egozim, Keshet Nehushah, Minhat Kohen, Pizei Ohev, and Yafik Razon, all works of interest and value, are proof of the adage in the Zohar that “all depends on mazal, even for a Sefer Torah in the Heikhal” (even a Torah scroll in the Temple requires luck to be selected to be read) ( Idra Rabba Nasso III: 143a).

Elkan Nathan Adler writes favorably that “[Doña] Reyna Duchess of Naxos, not only patronized Jewish printers but set up a printing press of her own at Belvedere, and afterwards at Kuru Tsheshme, near Constantinople; and it is largely owing to her liberality that the Sultan's dominions were, throughout the sixteenth century, distinguished for the best editions of the best works from the best MSS.”14 According to Avraham Yaari, as noted above, “it was certainly not Doña Reyna’s intent to engage in business and make a profit, but to enable Jewish scholars in Turkey and Eretz Israel to print their works, and she thus followed in the footsteps of her mother and husband, who assisted many scholars to print their books at the press of the brothers Jabez.”15

After printing ceased at Kuru Tsheshme, there was no permanent Hebrew press in or near Constantinople for approximately forty years.

* Marvin J. Heller is an award winning author of books and articles on early Hebrew printing and bibliography. Among his books are the Printing the Talmud series, The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book(s): An Abridged Thesaurus, and several collections of articles.

1 Concerning the dispute over the date of the Turim and its resolution see A. K. Offenberg, “The first printed book produced at Constantinople,” Studia Rosenthaliana, III (1969, reprinted in A Choice of Corals: Facets of Fifteenth-century Hebrew Printing, Nieuwkoop, 1992), pp. 102-32.

2 Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. Listing of Books Printed in Hebrew Letters Since the Beginning of Printing circa 1469 through 1863 II (Jerusalem, 1993-95), pp, 602-10 [Hebrew].

3 Concerning Doña Reyna and Don Joseph Nasi see Cecil Roth, The House of Nasi, The Duke of Naxos (Philadelphia, 1948). For Doña Gracia see, idem., The House of Nasi, Doña Gracia (Philadelphia, 1947).

4 Roth, The House of Nasi, The Duke of Naxos, p. 217.

5 A. M. Habermann, The History of the Hebrew Book: From Marks to Letters; From Scroll to Book (Jerusalem, 1968), p.125 [Hebrew]; Avraham Yaari, Hebrew Printing at Constantinople (Jerusalem, 1967), p. 32 [Hebrew].

6 Joseph Hacker, “Constantinople Prints,” Aresheth, V (Jerusalem, 1972), p. 492 n. 229 [Hebrew]; Yaari, pp. 229-31 no. 229. Isaac Yudlov, Ginzei Yisrael: The Israel Mehlman Collection in the Jewish National and University Library (Jerusalem, 1984), p. 236 no. 1547 [Hebrew with English Appendix].

7 Cecil Roth, The Duke of Naxos, (Philadelphia, 1948), pp. 218-19; Yaari, Constantinople, pp. 142-43 nos. 230, 233

8 Marvin J. Heller, The Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book (2 vols.) (Leiden, 2011), p 415).

9 Ch. B. Friedberg, History of Hebrew Typography in Italy, Spain-Portugal and the Turkey, from its beginning and formation about the year 1470 (Tel Aviv, 1956), 147 [Hebrew]

10 Raphael Nathan Nata Rabbinovicz, Ma'amar al Hadpasat ha-Talmud with additions [Hebrew], ed. A. M. Habermann, (Jerusalem, 1952), pp. 79-80.

11 Op cit., p. 80.

12 Concerning the various positions on this edition of Pesahim see Ephraim Deinard, Atikot Yehuda (Jerusalem, 1915), p. 43 [Hebrew]; Friedberg, p. 147; Israel Mehlman, “Notes and Additions to A. Yaari’s Hebrew Printing at Constantinople,” Kiryat Sefer, XLIII (1967), p. 577. [Hebrew]; Rabbinovicz, p. 80; Yaari, p. 33

13 http://aleph.nli.org.il/

14 Elkan Nathan Adler, “The Romance of Hebrew Printing” in About Hebrew Manuscripts (Oxford, 1905), pp. 128-29.

15 Yaari, p. 32.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800