THE SEPHARDIC SENSE OF PLACE(S) IN SHALACH MANOT’S HIS HUNDRED YEARS, A

TALE1

By GLORIA J. ASCHER2

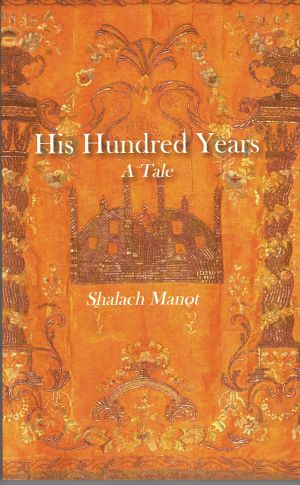

Cover art: "Torah Ark Curtain" from Istanbul, c. 1735.

The Jewish Museum, New York.

The H. Ephraim and Mordecai Benguiat Family Collection.

His Hundred Years, A Tale: the title of this Sephardic novel by Shalach Manot—a telling pen name –suggests an emphasis on time, rather than place. Yet it is location, specific places, that first impress themselves upon the reader, and the notion of place in the broadest and deepest— and very Sephardic—sense plays an essential role in this extraordinary work.

Already the cover of the book, what we first see and feel, evokes a place and a sense of place. Against a hazy, gold-bronze-rose-toned background, the smooth and shiny paperback cover features a Turkish Jewish image, adapted from an eighteenth-century Torah ark cover from Istanbul, now found in New York City’s Jewish Museum. Even before knowing the details of its origin, or recognizing the image of an Istanbul icon, we are transported to a faraway fantasy world, the world of “Turkish Jews,” a recurring designation in the novel. Coincidentally, or maybe not, various places in New York also become the scene of episodes in the “hundred years” of the main character’s life.

The titles of the twenty-eight unnumbered episodes, each identified in the Contents page, first by location and then by year, signal the importance of place. The specified locations are sometimes cities, like Çanakkale and Istanbul, but also both smaller and larger places, from streets and restaurants in New York and “The Kitchen in New Jersey” to “The Telephone” to “The Atlantic Ocean.” Though the first episode is the earliest, and the last one the most recent, the ones in between jump back and forth, in place as well as time, in no apparent order. Defying the limitations of narration in words, so convincingly delineated by the eighteenth-century German writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing in his Laokoon, Shalach Manot forces us to realize that, though the element of time is certainly important, the order and meaning of the years of a life are not ultimately determined by chronology. This realization forces us, in turn, to recognize the importance of place, which, though not the only determining factor, plays a crucial role in the lives of the main character and of other “Turkish Jews” we meet.

The location of the first episode is Çanakkale, identified as “a port across from Europe—on the Asian side of the Dardanelles,” “a magnificent nowhere-land” (1). It is the birthplace and boyhood home of the main character, who is identified not by name, but as “the boy” and later “the salesman.” He is already both—he is selling shirts his mother has made—his idea!—outside the mosque. In this first place he knows, likened to “a breeze-blessed paradise at the center of the world” (3), the boy is nourished by the Ladino songs his mother sings, the Alliance Israelite Universelle school he attends, and the early success he enjoys as a salesman, which gives rise to dreams of greater success, like that of the Biblical Joseph. In true Sephardic fashion, the boy is ready for adventures and challenges and appreciates and takes full advantage of what his native city and culture have to offer. But Çanakkale is so much more. The author details “What the boy never knew” about Çanakkale and nearby places: an incredibly rich historical and literary heritage, replete with connections, from Ovid’s Leander to Lord Byron to Homer’s tales of neighboring Troy. The awareness and celebration of multicultural connections is typically Sephardic. And so is the sense of connections and correspondences within the Jewish tradition in the immediately following passage, which closes the episode: “What the boy knew was that among the Jews of Çanakkale the men sang the Hebrew prayers every day, praising the same Ashem the Jews had sung to after Ur, in Egypt, in the desert, in Jerusalem, on the Iberian Peninsula, and here where they were welcomed to settle and sent ships for, in the Ottoman Empire.” (4) Çanakkale is depicted as a place which not only has specific, immediate impact, but connects and unites various cultures and times, evoking a typically Sephardic sense of place.

The Iberian Peninsula, mentioned in connection with Çanakkale, is not the scene of an episode, but appears again, in the story the now retired salesman tells an African-American boy on a flight to Uganda, about what he calls his ancestors’ “evacuation” from Spain (119). Another important place with no episode is France. Here the Alliance schools originated, as did “La Marseillaise,” which the main character sings as a boy (30) and as a man (23), at crucial times in his life, and, of course, the French language, which the old man speaks both in his family (35) and with Haitian nurses (26). All of this reflects the great impact of French culture on Turkish Jews. A place thus does not have to host an episode to be significant.

Istanbul, the place we encounter first, through the cover image, is the scene of two episodes. The first episode recounts the boy’s meeting with his father, who has left home both to escape conscription and to find work. Inspired by what he sees in this city, the boy is determined to “do something” and “make money.” The second episode in Istanbul, featuring the retired salesman, presents darker sides of Turkish Jewish life, most powerfully, the plight of women caught in a patriarchal society. The salesman’s “American wife” is shocked, angry, and also touched by the rage in Ladino directed at her by her aunt, who was “the only one” of her siblings left in Turkey to care for her mother, and, though she has raised a successful son, feels she is a sacrifice to family tradition. This episode stands in stark contrast to earlier, mainly positive depictions of Turkish Jewish life and places; we hear of “that stinking little town, Çanakkale”! (185)

Long Beach, Long Island, NY

The location of the last episode is “The Atlantic Ocean.” The salesman’s widow, at 97, is swimming with her noodle in Long Beach (New York). Said to have “finally learned the art of happiness” (191), she has become a worthy heir to her husband. With help she comes out of the water. Her granddaughter announces, “‘Here I am!’… her arms spread wide.” (194) So ends the Tale. In view of the roles of various places and of place in general, “wide” seems a fitting last word. Open, welcoming, all-encompassing, vast and broad, this human gesture corresponds to the ocean itself, the widest, all-connecting place in the novel—although the first location, Çanakkale, with its intriguing connections in the realms of both place and time, has an equally great sense of width and breadth. It is tempting to think even wider, broader when contemplating the Sephardic sense of place in this Tale. Amakom, the place, is also a name for God in the Jewish tradition. In Shalach Manot’s work, too, place is a relatively constant element, one inspiring awe.

Sien anyos en kadena es mas mijor de una ora debasho de la tierra/A hundred years in chains is better than one hour beneath the earth. Though not quoted in the novel, this Ladino proverb expresses the essential meaning of His Hundred Years: the value of life. The worst possible fate is defined in terms of place—beneath the earth, with the element of time—one hour—added for emphasis. In contrast, life, even a life of torture—A hundred years in chains—is not defined by place. Any place we are alive is acceptable!

This recalls another Ladino proverb: Ande stamos, bendigamos!/Let us bless where we are! Whatever our life is like here, we are alive, and there is thus no better place to be! And today at MLA3, we are in New York City! Ande stamos, bendigamos!

1 Manot, Shalach. His Hundred Years, A Tale. 2016. Boulder: Albion-Andalus.

2 Gloria J. Ascher is an independent teacher and Associate Professor Emerita of German, Scandinavian and Judaic Studies, Tufts University.

3 Modern Language Association's Convention held on the 4th of January 2018 in New York City.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800