Gila Green’s Cultural Worlds

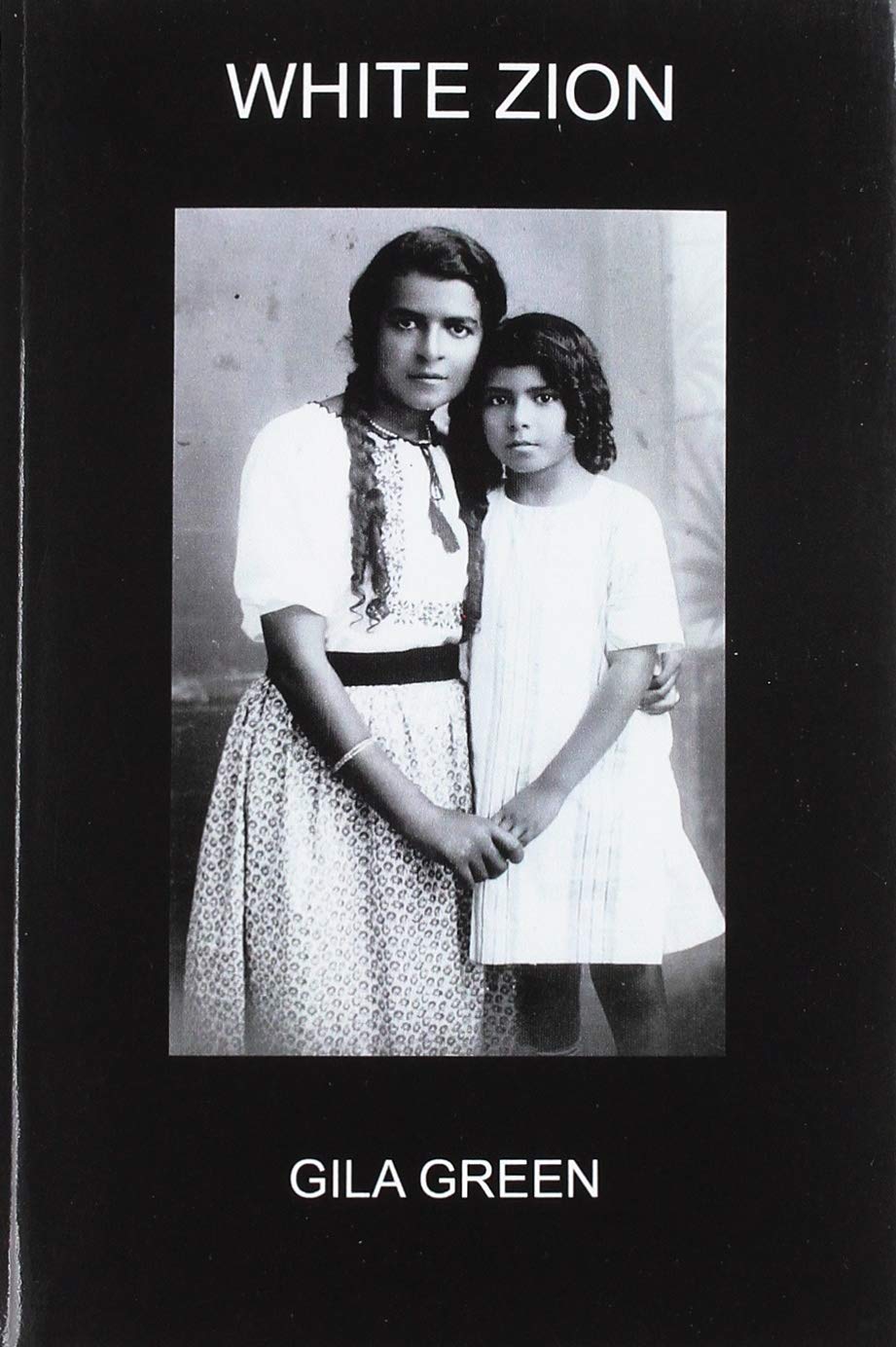

White Zion

Cervena Barva Press, 2019, ISBN-13: 978-1950063123

Reviewed by Susan Weintrob *

Gila Green’s White Zion, a collection of sixteen short stories, is filled with betrayals, humiliations, disappointments and strengths. Much of the focus is on Yemenite characters, their culture an exotic one from a Western point of view. Through her stories, Green reveals harsh conditions that made life difficult for the Temani immigrant both in Israel and Canada. White Zion is an ironic title built on the false assumption of many that Israel was built solely by the sweat and tears of pioneers who looked like Ben Gurion and Golda Meir.

The author’s parents come from distinct Jewish cultures. Her paternal ancestors left Yemen in the 1880’s for Ottoman Palestine; her father was raised in British Mandate Palestine while her mother grew up in Canada. Her characters are from the multi-cultural worlds in which she grew up in Canada and in Israel, to which she immigrated and now lives.

While some aspects of the stories have parallels to her own family, as in “The End of Jewish Jerusalem,” the stories are from Green’s own imagination. In this story, Assaf, the Israeli born father of Miri, the story’s narrator, now lives in Ottawa.

She thinks, “I never knew my father was Yemenite until I was already in university. My mother had told me he was Israeli and he was not a talker. I knew he was as strong as the desert heat and just as relentless” (“The End of Jewish Jerusalem,” White Zion, 29).

Assaf’s childhood was one of poverty, living without central heat on the edge of what became the new Jewish border of Israel. During the War for Independence, a provisional air force control room is set up on their roof. His mother sends Assaf up each morning for the soldiers’ leftovers, which gives the impoverished family their breakfast.

Assaf’s father, a loyal Mapai socialist in khaki clothes and a hat, not a kippah, is furious that an Ashkenazi from Russia received a promotion he wanted. Assaf’s mother answers him,

“Well, that’s your party,” she spits at him in Arabic… “You’re a token, Mordechai…One Kurdi, one Parsi, one Morrocai and one Temani…you’ll never go up more” (“The End of Jewish Jerusalem,” White Zion, 36).

Even as Mordechai bows to party leadership, his wife, bitter at this betrayal, is forced to create an equally bitter dinner: boiled wild grass in the week’s water rations.

In “Brass Knuckles,” conflict continues, this time between Canadian and Israeli culture. Language separates Miri’s parents. Her mother speaks English but not Hebrew. Her father speaks Hebrew, Arabic, some Farsee and rudimentary English. Both weaponize the language the other doesn’t know. Her mother doesn’t understand the obscenities her husband flings at her; her father can’t take messages on phone calls or bank alone. The characters play out the power of language to elevate and unite or separate and denigrate.

Both Miri and her father have dark skins and others often mistake them for Arabs or Mediterraneans. The stories show both Israeli and Canadian prejudice.

In this same story, a stinging episode reveals Muslim prejudice against Israelis. In a French bar, a drunken man flirts with Miri, telling her that she is “the most beautiful Iranian girl in this whole city.” When Miri protests that she is not Iranian, the man says, his hand brushing her shoulder, that as an Iranian himself, he knows she’s Iranian.

“Well, I’m Israeli actually.”

If I had told him I had AIDS after we had just shared one glass, he could not have reacted any differently. He jumped back, his facial expression had transformed from one of lust to one of disgust. The ranging began….I’m a murderer, a Nazi. I should be put behind barbed wire. I guess beauty is only skin deep. (“Brass Knuckles,” White Zion, 71)

Yemenite descendants face disappointments and humiliations from all quarters.

In a most poignant story in the collection, “Pita for Two,” Nomi, the mother of Assaf (now a paratrooper) takes in an abandoned nephew, Yoel. She scrapes by with cleaning houses, and then as she grows ill, she bakes a few saluf, Yemenite breads, in the front yard for a pittance to buy dinner. Yoel cleans and cooks, feeds the chickens and takes care of his aunt, who in her 40’s becomes weak and shows signs of dementia.

When Yoel is about 10, living with his aunt near the Machaneh Yehuda, he would stand

in the shuk, with the smell of freshly baked rolls and warm, white sugar making his mouth water, as he digs his hands deeper into his empty pockets. There was nothing to eat for breakfast. His stomach growls and he bows his head in shame (“Pita for Two,” White Zion, 46).

One day, he assists a woman laden with packages, helping to carry them to her home and dance studio in the Russian Quarter. She gives him a few coins and food. This becomes a regular routine and they build a relationship.

In a transformation of King Solomon’s judgment of two mothers claiming the same baby, Karina, the dancer, offers to take care of Yoel, have him live with her, feed him, send him to school and give him enough money to support Nomi.

Yoel focuses his large eyes on his aunt and her eyes meet his briefly. Then she is packing pitas carefully into a plastic bag. Yoel notices that she packs enough for two. He sits down silently on the ground between the two women. He is afraid if he opens his mouth he will cry (“Pita for Two,” White Zion, 62).

And like the two mothers who come to the king, Nomi gives her child up, with pain and tears but no Solomon is there to return the child to her.

Each story has its share of pain and disillusionment, as in “Modest Things,” where a Chasid molests an innocent boy, who confesses what happened to Miri, now a mother herself. “Roller Coaster” reveals a beleaguered Miri, mother of five, trying to shield herself and her family from her husband’s ire at their teenage son talking to a secular girl at an amusement park and befriending her on Facebook. Like her grandmother, Miri hides her pain, mechanically continuing nurturing tasks for her children. As in the metaphor of the roller coaster in the amusement park, she has no control until it and her husband’s anger comes to a stop.

In “Abba,” dysfunction is again part of the family dynamic: fights, hate and lack of security. During his youth, friendly relations existed with their Arab neighbors while within discord reigns until his parents divorce and finally the “years of screaming” were over.

We shared warm relations with the Arabs in the surrounding neighborhoods. Mother gave them strong coffee and cardamom cakes on their way to sell produce at Machaneh Yehudah and they gave her fresh dates and sabras in return (“Abba,” White Zion 111).

As well, this story reveals the difficulty experienced by Iraqi and Moroccan immigrants: backbreaking labor, poor housing and even poorer prospects. While the son is raised in much better economic condition than his grandparents or the Sephardic immigrants in the story, the quarrels inside his home sour his childhood.

Miri’s father remembers his paternal grandparents:

…the ones who lived without readily available water or electricity, down four flights of stairs in a basement, enjoy[ing] only peace and happiness in their home. We had lights, running water, a huge garden, and nothing but misery (“Abba,” White Zion, 128).

Parental love was as scarce a commodity as electricity and running water.

There is societal callousness that we find towards the marginalized. “Carob-colored” Mordechai at his Canadian wife’s family gatherings is often at the end of the table, almost out of the apartment, relegated to taking out the garbage. Nomi, after sacrificing for her sons and nephew, lives out her last days in a poorly supervised old age home. Dementia causes her to wander away and she falls into a ditch and dies, discovered by hikers three months later.

My father’s mother, whom I hardly knew, born in Tel Aviv when it was still Ottoman Palestine, died slowly in pain and alone, starved, dehydrated and abandoned in Jerusalem in a ditch—the way forgotten women do (“Nomi’s Tomb”, White Zion, 18).

Despite the economic, social or familial misery, there is strength in many characters. Miri’s father works hard both in Israel and as an immigrant to Canada. When Miri is grown up, living in Israel, her father writes her long letters by hand in Hebrew about his memories, always signing the letters with love. A picture on the wall shows him as a strong and young paratrooper. Yoel, abandoned in his youth, grows up to be an artist and writer. Nomi just about survives, yet always provides love. Miri’s ancestors emigrated from Yemen to Israel and then her father to Canada; then she reverses her father’s journey and returns to Israel. Miri is a thinker, a problem solver and in many ways an idealist, seeking home, security and peace.

Like other authors who create their own cultural worlds, in White Zion Green has developed realms filled with everyday details that are poignant, and at the same time, cruel and difficult. She is very adept at fixing the place, time and location in the reader’s mind. The place partially defines the characters, provides a tension in the plot and is the jumping off point of the stories’ development.

An interesting incident happened at my house that revealed a bit of the ignorance about Sephardic Jews that the title of the collection reveals. An acquaintance asked me what was on each doorpost and I explained they were mezzuzot and what was contained inside. She told me she especially liked a brightly embroidered one, a traditional Ethiopian design.

“Ethiopia!” she responded. “I didn’t know Jews were black!” A brief discussion followed on that point. I then explained how most Ethiopian Jews now lived in Israel because of persecution in Ethiopia, just as Sephardic Jews were persecuted in Arab countries and many left as well.

“I didn’t know Jews were ever persecuted,” she said.

Green’s stories in White Zion should answer my guest’s questions; she is not alone in her lack of understanding of Jewish diversity and the historic persecutions that were and are part of Jewish history. Even within the Jewish community, there is a lack of knowledge of the role of Sephardic Jews in Eretz Yisrael’s history and building. Certainly there is a hush about the discrimination suffered by dark skinned Jews by the Israeli Ashkenazi community.

About her own writing, Green notes, “My stories are about everyday people tackling immigration, racism, colonialism, occupation, alienation, war, politics, abuse, romance, poverty, terrorism, and survival.” Her writing is wonderfully evocative, revealed through her characters and plot and in their life difficulties. I was drawn in immediately and thought to myself, “Gila is a serious writer.” With four novels under her belt, Green engages with her prose in a way that makes her a writer to watch and read. She’s on my list to follow.

* Susan Weintrob is a retired literature instructor and Jewish Day School administrator. She writes full time in Charleston, SC, including a weekly food blog, a monthly Foodie Lit review both at expandthetable.net, regular book reviews on indiebrag.com and freelance articles on Jewish topics. Her great-grandmother spoke Ladino.