Sephardim among the Pioneers of the (American) West

By Andrée Aelion Brooks 1

When we think of the Jews who explored and settled the American West, we rarely stop to appreciate the contributions of the Sephardim. Our minds are more likely to dwell upon Conestoga Wagons and German Jewish immigrants like Levi Straus.

But the Sephardim were significant; in particular the conversos who came from Mexico City in the late 1500s, fleeing the reach of the Inquisition. And later on, the astonishing photos – the first of their kind -- that artist and photographer, Solomon Nunes Carvalho, took of the dramatic vistas, Native American settlements and soaring mountains of an interior land the wider world had only been able to conjure up in its imagination.

Even in the earliest days of the Spanish conquests in Mexico, the fear faced by the conversos of being arrested and thrown into inhuman conditions in prisons because of allegations of “Judaizing” – secretly practicing Jewish rites -- must have been overwhelming. Otherwise, why would so many have taken their lives in their hands to push into lands where – at least for the initial arrivals -- there were, as yet, no maps or destinations that could have provided succor or comfort; just the knowledge from captured “Indians” identifying the occasional Native American villages that might – or might not – be friendly.

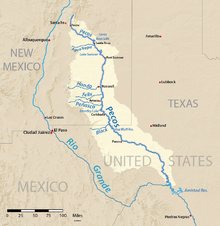

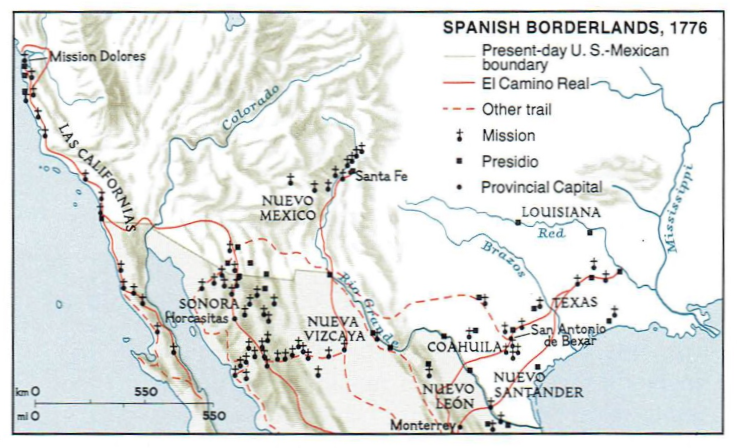

From National Geographic Historical Atlas of the United States, Random House, 2005

They were doubtless looking for safety rather than precious metals since many went with families and livestock. While the Southwest (Texas, California, Arizona, and New Mexico) was still under the Spanish, and part of Mexico, anyone able to claim additional land for Spain could be named governor of the newly-won lands, which tended to be in the far north. Once a converso was the governor of the province, such as Luis de Carvajal, governor of Nuevo León, according to Harriet and Fred Rochlin in Pioneer Jews: A New Life in the Far West, other conversos would also drift there. The governor could make it difficult for the Inquisition - established in the New World in 1569 – to operate in his territory.

Thus, conversos were already in the Southwest even while those territories still belonged to Spain. As an inducement to settle in these outlying areas, the Spanish government had been offering land grants. And so was established another first — the biggest and earliest ranches in the New World in the northern province of Nuevo León (eventually part of southern Texas) and adjoining areas such as New Mexico.

And though there were legends of a hidden Jewish past among the families that had owned them for generations, recent DNA tests, specifically for BRACA1, which was always considered a Jewish disease, albeit an Ashkenazi one at first, show a concentration of Sephardim emerging at the outset in Colorado and New Mexico. This was underscored in a talk given by science writer, Jeff Wheelwright, at the annual conference of the Society for Crypto-Judaic Studies in Denver in July, 2019.

At that conference, Rabbi Jordi Gendra-Molina, director of Casa Sefarad at Congregation Nahalat Shalom in Albuquerque, NM, added another reason to believe those conversos were among the earliest settlers. He talked about his current responsibilities certifying Sephardic ancestry for descendants now seeking Spanish citizenship. Based upon the towns where their ancestors had lived, they clearly mirrored the path these earliest settlers had taken northward alongside the Rio Grande (to remain close to fresh water) and what is known of the earliest family names. In sum: giving renewed confirmation that the conversos had indeed been prevalent among the first to forge a northward path.

The Carvajal family was among the most prominent of these settlers and explorers. In the beginning, in 1569, Luis de Carvajal y de la Cueva, a converso born in Portugal, conquered and ruled over a huge swath of Northern Mexico that included portions of today’s southwestern states, getting permission from the king in Madrid to bring with him families whose lineage was not to be questioned – one assumes that this was because they were likely to have been conversos.

But he was eventually brought down by the Inquisition anyway, for alleged secret Jewish practice, and arrested in 1589. His son, Carvajal the Younger, known as El Mozo, continued the famous horse- and catlle-breeding converso dynasty. That is why historians, such as Stanley Hordes, say that the largest ranches in Texas and New Mexico that date back to Spanish times were likely to have been started by conversos, settling as far away as possible from the center of the Inquisition. These frontier settlements – geographically remote and in need of goods and services -- became compelling as safe havens, even though conditions were primitive and dangerous (disease, Indian attacks). Some later boasted that they could even practice their Jewish rites openly, without fear, in such locations. They became zones of refuge.

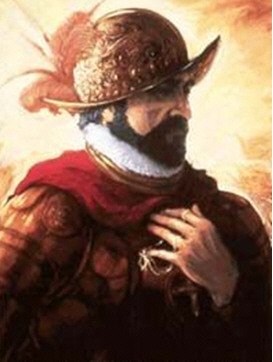

Another early conquistador, Gaspar Castaño de Sosa, identified as a converso by Stanley Hordes in his book To the End of the Earth (pp. 85–96) was a contemporary of Luis de Carvajal and originally one of his lieutenants. He came seeking mineral wealth such as silver, aiming to establish settlements along the banks of the wild Pecos River in a rugged and mountainous area (then at the end of identified lands) that is now mostly in West Texas and New Mexico. He must have been so desperate to mount his expedition (which seems to have included a significant number of conversos), based upon news of Carvajal’s arrest in 1590 by the Inquisition, that he got tired of waiting for official permission and went anyway – significantly without a priest among them, which would have been contrary to normal practice.

Where he crossed the Rio Grande was later known colloquially by some as “el paso grande de los judios” (Hordes p. 81). It was not long before the viceroy in Mexico City found out and ordered a scouting party to go and arrest Castaño. He was placed in shackles and began the long trek with his captors back to Mexico City. On the way he wrote to the viceroy explaining he had no intention of disobeying the law. He had written for prior permission and assumed it would be granted. But his appeal letter never arrived. Moreover, he had discovered lead and silver mines valuable to the crown. To no avail.

Rather than being feted for his discoveries and establishing new Spanish settlements, he was eventually sentenced to exile in the Philippines, where he was killed during a mutiny on a Chinese junk. He had meanwhile had his conviction overturned by the Council for the Indies back in Seville, but did not survive to savor his victory. After his departure, the Spanish settlers scattered and it took another attempt to create a settlement that would last.

About five years after Castaňo was arrested, the governor had still not established a viable, stable, defensive, and permanent community on Mexico’s northern frontier. Enter Juan de Oñate who came from a distinguished Spanish (previously Jewish but this was never officially mentioned) family who had all the needed credentials: experience of the settlements, time as a soldier, explorer, and miner. His contract called for 200 fully armed men, livestock and supplies – and families. Some were survivors of Castaño’s expedition. One family’s inventory was listed as two swords, a javelin, a lance, a harquebus, a pistol, twenty horses, some with armor, and six mules. Others brought oxen and ploughs. He departed in 1597 with 460 people in all.

Oñate became the first governor of New Mexico. He established his capital at the confluence of the Rio Grande and the Rio Chama, just southwest of modern-day Taos. However, Oñate has become a controversial figure. The local Native American tribes now argue that his cruelty to their people should preclude him from being honored, even having a life-size statue adorning the entrance to El Paso International airport removed, among other sites.

The contributions of these first Spanish pioneers and subsequent expeditions to North America also provided the earliest introduction of: the Spanish language, Christianity, Jews, European musical instruments, farming and mining equipment, spices, cookware, fruit-tree cuttings, seeds, and domestic animals that included cattle, pigs and goats. Most dramatic historically among the livestock introduced during the Oñate expedition was the horse - war horses and mares – which became so vital to Native Americans in subsequent years.

Once established, those northern provinces also became an ideal location for later arrivals of conversos to engage in their characteristic Jewish role as traders. They provided these early settlements, mining camps, and isolated ranches with merchandise not easily found locally, through their international trading networks: silks from Asia, clothing, spices, and so forth. And for generations they would keep their family networks intact through marriages among themselves.

Their number further included the earliest cowboys. During the days when these states were still part of Spanish Mexico, some of those settlers headed even further north and east to become the first cowboys in the New World – a story told by Deanne Stillman in Mustang: The Saga of the Wild Horse in the American West. “Some secret Hebrews eluded their tormentors, and within another hundred years,” she wrote, “the original high plains drifter of American legend was not Clint Eastwood or Gary Cooper, but a son of Moses who had been kicked out of Spain.”

Some conversos also distinguished themselves early on as military officers and political leaders and became crucial to spearheading the early development of the Spanish Catholic heritage in the Southwest. But as the generations continued, their identities became woven so deeply into the regular Catholic communities that it was hard to know the difference – not emerging again until an awareness of a possible crypto-Jewish heritage started to gain attention and trigger research about 40 years ago – and is now very much part of Southwestern history.

The next wave of Sephardic Jews to settle the West should have logically been the many merchants who had first come up from the Caribbean islands to expand their Atlantic trading networks in the increasingly prosperous Southern cities of Charleston, Savannah and New Orleans – and migrated west from there. They would have therefore been primarily traders, like the immigrant German Jews whose names and deeds fill this historical gap.

But aside from such characters as the pirate, Jean Lafitte, in the 1700s, who speaks in his journal (The Journal of Jean Lafitte) about his Spanish Jewish grandmother, we hear nothing about them individually or collectively. The major settlement of Sephardic Jews, such as the one in Seattle, would not take place until the end of the 19th century.

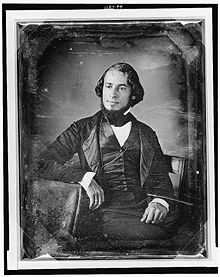

But there was one notable exception, although neither trader nor religious fugitive. His name was Solomon Nunes Carvalho, a photographer and artist who gave us some of the first iconic images of the West. A man of Portuguese Jewish descent, he was born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1815. His family, active in Jewish communal affairs, had come there by way of Amsterdam, London and Barbados. It was an upper-middle class intellectual environment which seems to have left him close to his Jewish roots all his life.

From early childhood, he had demonstrated a remarkable ability in art, especially portrait painting. He was equally fascinated by the earliest forms of proto-photography known as daguerreotypes. Moving to Philadelphia as a young man, he was soon sought out by Colonel John Charles Fremont, one of the best-known explorers of the American West. Fremont had been asked to scout out a possible route for an all-weather railroad across the middle of the country. He needed someone to create images of the potential route, especially someone sufficiently familiar with the intricacies of the early daguerreotypes to overcome the severe weather conditions they would encounter.

Carvalho jumped at the chance. But weather conditions were crippling, although the vistas were awesome. Their horses died and were eaten by the starving company. Many of the group soon had frozen hands and feet, huddled as they were in icy and tattered blankets. But still they moved westward; Carvalho taking pictures or making sketches under brutal conditions much of the time.

Keeping kosher was out of the question when keeping alive was all that counted. He wrote in his diary that on May 29, 1854, when they were camped near a narrow stream “of deliciously cool water“ on ground in Nevada that was called by the Mexicans, “Las Vegas” (a Spanish term for meadows), he refused at first to eat with the other travelers, as their chosen dinner was porcupine (a favorite survival food on the trail) because, “it looked very much like pork. My stomach revolted, and I sat hungry around our mess, looking at my comrades enjoying it.”

He attempted to avoid the horse meat too. Still, when the dying animals were slaughtered and their blood drained into the camp’s kettles (widely used for sauces), he said he continued to have a problem digesting the food. Eventually he became too ill to continue. What remained of the expedition left him behind in a Mormon village where the residents nursed him back to health.

While there, he recorded a strange sight. “It was hinted to me,” he later wrote, “that Mr. Heap had two wives. I saw two matrons in his house, both performing the duties of maternity; but I could hardly realize the fact that two wives could be reconciled to live together in one house. I asked Mr. Heap if both these ladies were his wives, he told me they were. On conversing with them subsequently, I discovered that … Mr. Heap had married three sisters, and there were living children from them all. I thought of that command in the Bible, “Thou shalt not take a wife's sister, to vex her’. But it was no business of mine.”

Now on his own, his precious photos and sketches having been taken forward by Fremont, he pushed on to the West Coast himself, as soon as he regained his strength. Arriving in Los Angeles, Carvalho sought out members of the tiny Jewish community. There were only about thirty Jews living in Los Angeles then. They did not even have a synagogue or a cemetery.

Carvalho only stayed a month, but in that brief period he helped the Jewish community organize the Hebrew Benevolent Society -- the first Jewish society in Southern California. Its mission was to help one another at moments of sickness and setbacks and to purchase funeral plots for the poor. Carvalho makes no mention of whether any of the five founding officers were of Sephardic descent like himself. But two of their family names are associated with Sephardim: Labatt and Elias.

And what of his pictures? The valuable daguerreotypes that Carvalho worked so hard to create and preserve were eventually turned over to the famed photographer Mathew Brady for reasons unknown, perhaps because Carvalho was still so weak. After a disastrous fire, most of Carvalho’s daguerreotypes were nothing but ash. A few survived and have with effort been identified as being created by him, such as the daguerreotype of Wild Horse Butte. The rest perished.

The failures mounted. Fremont’s recommendation for his particular railroad route along the ground they had covered was never built. The only eye witness account of the expedition was the book that Carvalho wrote himself, selling the rights for a mere $200 because he had become so hard up – only to face added anguish when the book became a best seller.

Now living In New York, Carvalho, along with his wife, Sara, continued to pursue his interest in Jewish life, founding a small synagogue in Harlem in 1870. He then turned his talents to the invention of a steam boiler that was eventually used in foundries and factories all over the United States. Even so, he never seemed to have profited much from his work. He died in May, 1897. He is buried in the Beth Olam cemetery of Shearith Israel, the Spanish and Portuguese synagogue that now stands on West 70th street and Central Park West; essentially an outstanding talent the world never adequately honored.

Source: this article has been adapted from a four-part mini-course given in the spring of 2019 at the Jewish Community Center in New York City, among other locations, by Andrée Aelion Brooks.

References

Hordes, Stanley. 2008. To the End of the Earth: A History of the Crypto-Jews of New Mexico. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lafitte, Jean. 2009. The Journal of Jean Lafitte: The Privateer-Patriot’s own Story. N.P.: Moonglow Books.

Libo, Kenneth and Irving Howe. 1984.We Lived there Too: In their own Words and Pictures, Pioneer Jews and the Westward Movement of America, 1630-1930. New York: St Martin’s Press/Marek.

Nunes Carvalho, Solomon. 2004. Incidents of Travel and Adventure in the Far West with Colonel Fremont’s Last Expedition. 1853-54. Nebraska; University of Nebraska Press, Bison Books.

Rischin, Moses and John Livingston eds. 1991. Jews of the American West. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Carvalho’s Journey. 2015. Dir. Steve Rivo. Down Low Pictures.

Rochlin, Harriet and Fred. 2014. Pioneer Jews: A New Life in the Far West. N.P.: iUniverse.

Stillman, Deanne. 2009. Mustang: The Saga of the Wild Horse in the American West. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

1 Andrée Aelion Brooks is an author, historian and journalist. She is an Associate Fellow, Yale University. Brooks recently won a Rockover Award for Excellence in Jewish Journalism from the American Jewish Press Association. She can be reached at andreebrooks@hotmail.com. Website: andreeaelionbrooks.com.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800