The Taranto-Capouya-Crespin Family History:

A Microcosm of Sephardic History

By Leon B. Taranto1

© 11 June 2011

Part I. The Taranto Family

From Rhodes to America: Our First Pioneers

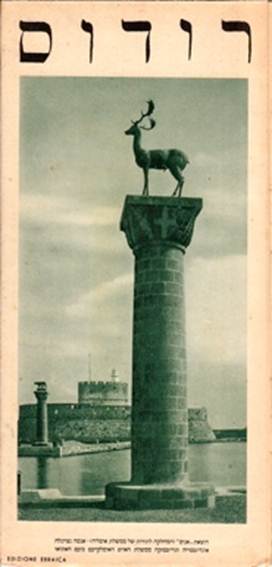

Rhodes harbor and stag, 1930s

Rhodes harbor and stag, 1930s

Leon Benison Taranto, Leah Capouya and sons

Leon Benison Taranto, Leah Capouya and sons

This history2 commemorates our Mediterranean Sephardi families and resettlement in America over a century ago, which began when the S.S. Laura, originating in Patras, Akhaia, Peloponnesus, Greece, steamed into the Port of New York on May 30, 1907, with Leah and Bension’s eldest son, young Ephraim Taranto.3 Described as a Turkish-Hebrew laborer age 19, ‘Efraim’ traveled with his uncle, ‘Elia Kapouya’ (Eli Capouya), b. 1888 Rhodes.4

The ship manifest tells us Ephraim stood at 5 feet 7 inches, and could read and write. He and Uncle Eli, Leah’s youngest brother, were headed for 2945 W. 5th Street in New York, to stay with A. Bonomo, identified as Ephraim’s cousin and Elia’s uncle. Ephraim’s mother Leah and her brother Eli were likely related to A. Bonomo, as their maternal grandmother was Signoru (Sinyuru) Bonomo of Smyrna (Izmir), wife of Haham Yehuda (Giuda/Leon) Crespin.5

Ephraim and Eli soon moved to Montgomery, helping to found the Rhodeslis colony that has flourished there for over a century. Two years later, on March 25, 1908, Ephraim’s brother Joe arrived from Rhodes aboard the same vessel, S.S. Laura, repeating the Patras to New York voyage. The ship manifest lists ‘Jossif Taranto,’ single, age 18, from ‘Rodos’ [Rhodes], of Hebrew and Turkish ethnicity, placing his birth around 1890. Described as of dark complexion with brown eyes and hair, no marks, and in good health, Joe paid his own passage, entering America with $15. While the manifest tells us Joe was in route to see his ‘friend’ Gerrasimos Debonerous in Albany, New York, he later joined Ephraim in Montgomery, forming the American nucleus of our Taranto family. Bension followed in June 1911, with his eldest daughters, Sultana and Sadie. Sultana, wife of Solomon Rousso, would soon give birth in early 1912 to the first Taranto grandchild, Morris Rousso, and Sadie would marry Ralph Cohen, a Rhodeslis pioneer of the Montgomery community. With the 1912 arrival of Leah and the seven youngest children, all of the Bension Taranto family settled in Montgomery. That same year, Solomon became the first President of the city’s Etz Ahayem congregation, serving until 1937.

Leah and Bension: Their Ancestral Families and Eleven Children

Rodos harbor and medieval city

Bension descends from the Taranto and Algranate families and, through his mother, the Beresit and Aboaf families. Leah’s father is from the Capouya and Capelluto families, while her mother is from the Crespin, Israel and Ben-Habib (Habib) rabbinical families of the eastern Mediterranean, tracing to the 1500s and 1600s, and the Bonomo family of Izmir. Bension, his wife Leah, and their eleven children, were born on the Isle of Rhodes, then part of the Ottoman Empire. Rhodes passed to Italian rule in 1912, as Leah and the seven youngest children left to join their family in America. Greece annexed Rhodes in 1947, following the defeat of Nazi Germany, which had destroyed virtually the entire Jewish community. In birth order, the eleven Taranto children were:

Name |

Birth |

Death |

Sultana Taranto Rousso |

1889-90 (20 Aug 1891) |

12 Apr 1920 |

Ephraim Toranto |

1888-91 (15 Sep 1890; 24 Feb’91) |

10 May 1964 |

Sadie Taranto Cohen/Yohai |

1892-94 |

12 Mar 1965 |

Joe (Joseph) Benson Toranto |

1890-98 (4 Mar 1890, 1900) |

11 Mar 1977 |

Catherine Taranto Galanti |

1896-1900 (Dec 1900) |

25 May 1978 |

Esther\Diana Taranto Capouano |

1900-03 (Apr 1903) |

11 July 1945 |

Yom Tov Taranto |

1902-03 |

20 Feb 1917 |

Julia Taranto Pinto |

1903-04 (29 Nov 1903-04) |

12 July 1983 |

Al (Abraham) Toranto |

1904-06 (6 Apr 1905-06; 23 Dec 1906) |

23 Jan 1979 |

Morris (Moise) Ben Taranto |

1905-08 (15 Sep 1906, 1908) |

17 Mar 1989 |

Alice (Elisa) Taranto |

1907-10 (1 Sep 1909) |

4 Mar 1933 |

Bension and his Taranto Family

Asansor (elevator) tower to

Karatas quarter, Izmir

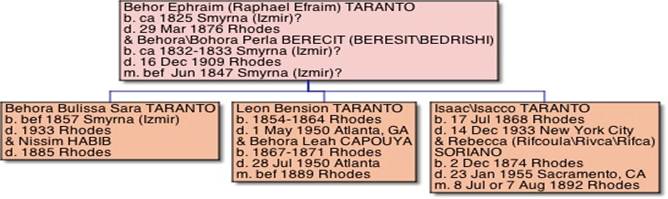

Born on Rhodes around 1857, Leon Bension Taranto was the second of three children of Ephraim Taranto and his wife Perla Berecit (Beresit/Bedrishi). Ephraim and Perla were originally from Izmir (Smyrna), the principal port of western Turkey.6 Bension was born after Ephraim and Perla moved to Rhodes. His older sister was Behora, an honorific name for the first born if a girl.7 They had a younger brother, Isaac. Living in the late 19th century Ottoman Empire, our patriarch (Bension or his father Ephraim) was a fez maker. According to family legend, he made them even for the Sultan. Ephraim and Perla lived out their days on Rhodes, where they are buried.8 One of Perla’s dreams was to visit Israel, which she did twice in her lifetime.

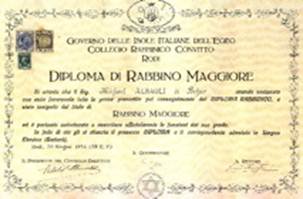

Rabbinical diploma of Michel Albagli, Rhodes

Bension’s sister Behora Bulissa Sara Taranto (d. 1933, or the Hebrew year 5693) also lies in the Rhodes Jewish cemetery, where her gravestone is beside that of her husband Nissim Habib (d. 1885), and her parents.9 Behora and Nissim had a daughter Rebecca, born on Rhodes on October 25, 1886. In 1907 she wed Abramo (Avram) Habib, also on Rhodes. Both were still living in 1938, and recorded in the Italian census of the Jews of Rhodes taken late that year. On May 10, 1912, Rebecca gave birth to a daughter Zelda, who in 1931 wed Natan Rozio (Rosio) on Rhodes. They had three children, Israele (b. 19 Sept. 1932), Abramo or Avram (b. 11 Nov. 1934), and Sara (b. 3 Nov. 1936). In summer 1944, the Germans deported Zelda and her three young children, ages 7, 9, and 11, to Auschwitz with over 1700 Jews of Rhodes and Cos. They perished in the Shoah, like over 90% of the Jews deported from Rhodes.10

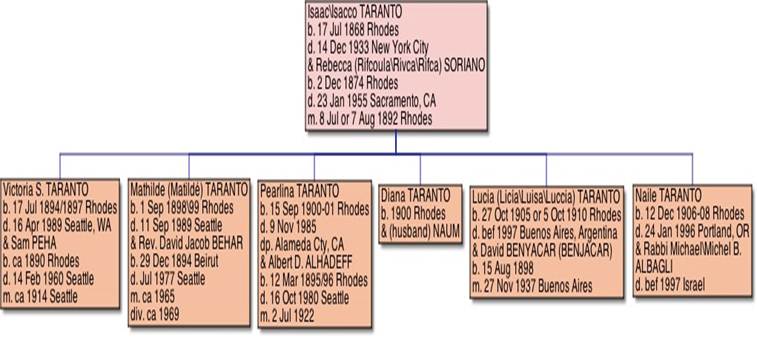

Bension’s brother Isaac married Rebecca Soriano, whose nephew Maurice (Moise) Soriano (d. July 2002) lived his 99 years on Rhodes.11 Isaac and Rebecca had six daughters, all immigrating to the Americas.12 The first three were Victoria Taranto Peha (17 July 1894 - April 1989), Pearlina Taranto Alhadeff (b. ca 1895-97), and Matilda (Mathilda) Taranto Behar (1 Sept. 1898 - 11 Sept. 1989), followed by Naile Taranto Albagli (b. ca. 1908-09), Lucia Taranto Benyacar (Benjacar), and Diana Taranto Naum. All six were highly educated. Victoria and Mathilda were teachers in Rhodes.13

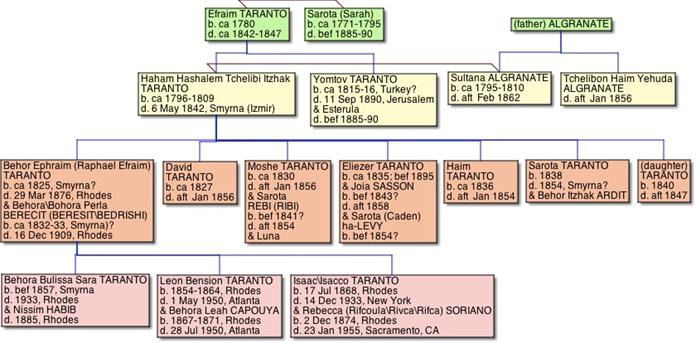

Ephraim Taranto and Perla Beresit family tree

In the early 1930s, as the fez industry decline threatened the Tarantos’ livelihood, Isaac left Rhodes for America, staying in Seattle with his eldest two daughters Victoria (Mrs. Sam Solomon Peha) and Pearlina (Mrs. Albert Alhadeff). His wife and youngest daughters remained in Rhodes until he could send for them. On his way to the docks in New York to board a ship to Rhodes to bring his wife and daughters to America, Isaac was hit by automobile. His trunk arrived in Rhodes, but Isaac died and was buried in New York. Grandson Joe Peha recounts that by coincidence a Taranto nephew was interning at the hospital where Isaac was taken and cared for him in the emergency room. This was Bension’s youngest son, Dr. Morris Taranto, an intern at Mt. Sinai Hospital around 1933-34.

Isaac Taranto and Rebecca Soriano family tree

Within a few years of Isaac’s death, his wife Rebecca and the remaining daughters left Rhodes for the Americas. Diana and Lucia moved to Buenos Aires,14 Rebecca and the other two daughters to the United States. Naile, age 30, arrived at the Port of New York in February 1939, eventually settling in Portland, Oregon with her husband Rabbi Michael (Michel) Albagli, who headed Ahavath Ahim, its Sephardic synagogue. On Rhodes, Naile was a midwife and Rabbi Albagli was the last head of the Collegio Rabbinico (Rabbinical College). Established in 1928 under Italian government auspices, the Rabbinical Seminary flourished until 1938, when the Mussolini regime abruptly closed it down as Fascist Italy aligned with Adolf Hitler.15 Mathilde, age 40, and her widowed mother Rebecca left Rhodes on the last ship before Italy entered the Second World War. In May 1940, right before the fall of France, they arrived at the Port of New York.16

Tarantos of Smyrna – and DNA Connections

Title history for yard in Ergat Bazar, Smyrna, 1862

Our Taranto family includes 1400 descendants of two Taranto brothers born in the late 1700s who lived in Smyrna (Izmir). My early reconstruction of our Taranto genealogy is detailed in the article: Leon Taranto, “Izmir and Rhodes: Taranto Family Origins, Archives, and Links to other Sephardim,” ETSI - Revue de Genéalogie et d'Histoire Sépharades (Sephardi Genealogical and Historical Review), vol. 15, pp. 3-9, Dec. 2001.

Exciting breakthroughs in genetic testing reveal that our family is part of a Taranto family with two other branches from Izmir, for another 250 descendants, and 1600 Tarantos in all. FamilyTreeDNA analyzed DNA samples contributed by Avram Taranto of Istanbul, Irwin Taranto of California, and me (Leon Taranto), as participants in a genetic study for mapping Sephardi migrations. The perfect 12-point match on Y-chromosome testing for these DNA samples establishes that our most recent common ancestor (MRCA) was likely born no earlier than seven generations or 200 years before Avram, Irwin and Leon. Using the median birth year of 1944, the MRCA was likely born in or after the 1740s. Coordinated by Alain Farhi of Les Fleurs de L’Orient, this university-conducted Sephardi genealogy study17 also produced identical matches for DNA samples from several Rousso branches, including the Moussani Rousso branch of our Rousso cousins.18 Some other families tested are Pizante, Capouya, and Alhadeff. More recently, a DNA genealogy project for Rhodesli families was started by Dr. Robert (Bob) Rubin, also through FamilyTree DNA, has produced new matches. Our Taranto family is part of that study as well.

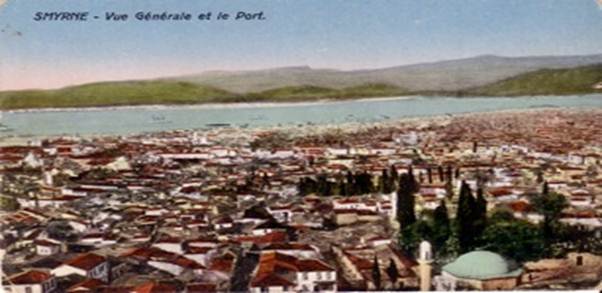

Smyrna (Izmir) general view of the port

There are a few hundred descendants from other Sephardi Taranto families, primarily from Izmir and Istanbul, but also Edirne, in Turkey, whose relationship to us awaits confirmation. In the nineteenth century, most Taranto Sephardim lived in Smyrna (Izmir), like our own branch before migrating to Rhodes in the 1850s. Others lived in European Turkey (Istanbul, Edirne), Bulgaria (Sofia, Plovdiv), Israel (Jerusalem), Egypt, and even Germany (Hamburg). The first Tarantos likely arrived in Izmir between the early 1600s, when Sephardim first settled there as Ottoman Turkey developed this port,19 and 1780, when an Isaac Taranto, son of Shaul, signed as a donor and member of congregation Hevra Kadisha in Izmir.20

Taranto Brothers Efraim & Haim Moshe

The earliest known history for our Taranto family begins with Efraim Taranto (b. ca 1780), his older brother Haim Moshe Taranto (b. 1772), and their mother, Zinbul.21 This Efraim was the great-grandfather to Leon Bension Taranto (ca 1857-1950). Since both Haim Moshe and Efraim named their first-born son Itzhak, we can speculate that their father was also Itzhak. Efraim and his wife Sarota (daughter of Reina) had two sons, Tchelibi Itzhak Taranto (Itzhak) and his younger brother Yomtov (b. ca 1816), a banker.22

Smyrna (Izmir) view of the Quarantaine

Itzhak and his wife Sultana Algranate had seven children. The eldest, Behor Ephraim Taranto (b. ca 1825), was Bension's father. Like his parents Efraim and Sarota, Itzhak and Sultana lived in Izmir. The signature of our ancestor Itzhak ben Efraim Taranto, or perhaps of his namesake an earlier Itzhak ben Efraim Taranto, is preserved today at the Ben-Zvi Institute Library in Jerusalem, on the title page of Rabbi Shelomo Ben-Aderet’s book Hidushei Nida, published in Altona in 1737.23

Yomtov Taranto Establishes Synagogue de Taranto in Jerusalem

Eulogy for Haham Tchelibi Itzhak Taranto

Tchelibi Itzhak Taranto’s younger brother Yomtov, great-uncle to Itzhak’s grandson Leon Bension Taranto, lived to about 1890, surviving his wife Esterula. As Yomtov and Esterula were childless, Yomtov arranged financing for a group of ‘Hahamim’ to assemble to study Torah portions on the anniversaries of their deaths, and the deaths of his parents. A circa 1885-90 document from Ben Zvi Institute, found by Rabbi Dov Cohen of BZI, details these arrangements and identifies Yomtov’s (and Itzhak's) grandmothers as Zinbul (Efraim’s mother) and Reina (Sarota’s mother).

Yom Tov Taranto Synagogue, Jerusalem

From Yaakov Taranto of B’nei B’rak in Israel, I learned of the Synagogue de Taranto in Jerusalem. It is located in Ohel Moshe, a neighborhood of small stone houses surrounding a large cobble square. Situated a bit west of the Yemin Moshe, Ohel Moshe was built in 1882 by Sephardim and named for Sir Moses Montefiore, who donated funds establishing this community.24 The Taranto synagogue was established by “Yom Tov fils de Efraim Taranto,” who must be the same as person as Yomtov Taranto of our family, brother to our ancestor Itzhak Taranto, sons of Efraim Taranto (b. circa 1780).25 A plaque or information at the Taranto Synagogue shows September 11, 1890 (26 Elul 5650) as the death date for Yomtov Taranto. The photo of the synagogue’s entrance gate identifies Yomtov Taranto as Efraim’s son and states that the synagogue was founded 1890. Our Parisian cousin Roland Taranto provided this photograph of the Yomtov Taranto Synagogue entrance, taken by his brother-in-law. Mathilde Tagger, a friend in Jerusalem, notes that the book Nahalaot belev haIr: lesayer im yad ben Zvi [Neighborhoods in the heart of the city: Touring with Yad Ben Zvi] published by Yad Ben Zvi (Ben Zvi Institute), Jerusalem 2000, p. 312, contains a plate of a Hebrew inscription from the synagogue, which she translates:

Kodesh LeAdonai

Mimeni Yom Tov Ben

Efraim Taranto HY"V [acronym of Adonai Yishemeru veYehayehu]

Lo leMekhira[Holy place for G-d

From me Yom Tov son of

Ephraim Taranto May G-d keep him save (safe?) and alive

Not to be sold]

The Legacy and Family of Haham Itzhak

Tchelibi Taranto

Taranto family tree, 1700s to 1950s

The Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People (CAHJP) at Hebrew University in Jerusalem contain key documents for our Taranto family. CAHJP's collection from the Rabbinate of Izmir includes two documents on the legacy of Tchelibi Itzhak Taranto, Bension's grandfather. The first, dated 20 Shevat 5613 (29 Jan. 1853), recounts that ‘Haham Shalem’ Rabbi Itzhak Taranto, called Tchelibi, died some years previously, survived by his widow Sultana, his five sons Behor, David, Moshe, Eliezer and Haim, and unidentified orphans.26 The Rabbinical Court appointed Rabbi Shemuel Hakim and Haham Itzhak Yeshurun as custodians for the orphans. Sultana arranged for the Rabbinical Court to designate her brother-in-law Yomtov Taranto to care for Tchelibi Itzhak’s properties and any profits generated. Now reaching majority, the orphans asked the Rabbinical Court to account for their properties. Presenting all the bills, their Uncle Yomtov demonstrated there were no debts.

Ergat Bazaar (Irgatpazari), Izmir, 2011

The second CAHJP document, prepared in Izmir in February 1862 (Adar I 5622), recounts that on October 18, 1817 (8 Heshvan 5578), the ‘guevir’ [rich] brothers Haim Moshe Taranto and Efraim Taranto purchased a yard (El Kortijo de Katan) in Ergat Bazar,27 an Izmir neighborhood, along a small lane Kalejica de Gan, from Behor Yossef Benveniste ben Itzhak and his wife Clara for 9,000 araiot, witnessed by Rabbis Yossef Benezra and Yehoshua Moshe Mordehay Crespin (Leah Capouya’s great-grandfather).28 On July 29, 1832 (2 Av 5592), Efraim Taranto purchased the interest of his brother Haim Moshe Taranto and wife Simcha for 7,000 araiot, witnessed by Rabbis Yehoshua Moshe Mordehay Crespin and Moshe Albagli.29 Years later, Efraim died, survived by his wealthy son Yomtov Taranto and grandchildren through his elder son Rabbi Tchelibi Itzhak Taranto. The seven grandchildren were Behor Ephraim, David, Moshe, a boy Eliezer, a small orphan Haim, and two little orphan girls for whom the Rabbinical Court (Beit Din) appointed guardians. After the orphans grew, Tchelibi Itzhak's widow Sultana demanded payment for her Ketuba. At the end of Sivan 5607 (June 1847) the four elder sons and guardians sold their half of the yard to her for 8,000 araiot. Rabbi Aharon Crespin signed for Behor Ephraim’s wife Perla (Bension's mother). Sultana and her brother-in-law Yomtov each now owned half.30

Our Belgian cousin Sonja Bilé Vansteenkiste, who visited Izmir this year, and Avram Aji, a Taranto cousin remaining in Izmir today, have explained that Ergat Bazaar (Irgatpasari) was a place for hiring daily laborers. Run-down today, the area is near Izmir’s bazaar and old Jewish quarter, where several older synagogues are a testament to the large Jewish community that thrived there in the 1800s and early 1900s.

Rabbinical eulogies attest to Tchelibi Itzhak Taranto’s prominence. Rabbi Haim Moshe Matzliah of Izmir and Tire (d. 1845) lamented:

Portion [of Torah] Shelah-leha, preach number one. Preach I told on the “shloshim” (thirty day of mourning) for the death of Ahaham Hashalem Rabbi Itzhak Taranto z”l [of blessed memory], and for the death of my friend … Rabbi Hayim Yossef Hacohen Arias z”l, in the Mahazikey Tora sinagogue [Izmir], 5602 (June 4, 1842). People will cry and complain for the misfortune of the young and righteous men death, in particular who we are eulogizing about [R. Itzhak Taranto], who was desolated for his hard suffering, that entire year he was very sick, could not to speak, and he was an honest and pious man, sage and practise on the Torah …31

A second eulogy, by Rabbi Mercado Behor Nissim Yaacov Mizrahi of Izmir (d. 1866), also laments the protracted illness and passing of the sage Itzhak Taranto:

Fifth preach (for) eulogy. Took place at “Shalom” Synagogue [Izmir], Shabat evening, seventh day for the death of my uncle Haham Hashalem Yaacov Cohen … this was a hard year by all the dolour and misfortune we suffered … first the big fire (July 29, 1841) … the synagogues were burned … also much schools (Beth Misrash) with the books, “Tefilin” and "Mezuzor" … Beside the loss of some sages (talmidei hahamim) … Rabbi Moshe Bengabay … Haham Yossef HaCohen … also the passing of Rabbi Itz[hak] Taranto z”l, who suffered strong agony, and almost six months was moribund [sickbed] …32

Holy Ark, Algaze synagogue, Izmir

From another document we learn Tchelibi Itzhak Taranto’s widow Sultana was an Algranate, an Izmirli family harkening to the Sephardi ‘golden age’ in Granada.33 Dov Cohen identifies a Beit Din “pinkas” entry from Izmir, 14 Shevat 5616 (12 Jan. 1856), on the death of Sarota, wife of (Behor) Itzhak Ardit (Haham Yeoshua Ardit’s son) “around one year and a half ago,” leaving no children, and her goods returning to her family. Heirs were her five brothers - Efraim Behor (Bension’s father), David, Moshe, Eliezer and Haim Taranto - and mother Sultana, widow of Haham Tchelibi Itzhak Taranto. Sultana's brother Tchelibon Haim Yehuda Algranate was named broker for the heirs.

Perla and Ephraim Taranto Migrate to Rhodes

Ephraim and Perla moved to Rhodes partially for the better weather, but also because they believed that in Rhodes they would have a son. And there they were blessed with two sons, Bension and Isaac. Ephraim Taranto appears in the tax records for Rhodes for 1855, 1858, 1861, 1863, and 1869, confirming his residency there. Ephraim is not listed in 1852, presumably because he and Perla had not yet left Izmir. Ephraim was likely at least middle class, as his taxes exceeded sums for most taxpayers. Census records at the Rhodes Jewish Community Office later list him as “Efraim Taranto,” father of Bension Taranto, and “Bohor Taranto,” father of Isaac (Isacco) Taranto (Bension's brother). Behor Efraim’s gravestone identifies his father as Haham Hashalem Tchelibi Itzhak Taranto. (Behora Perla Taranto’s stone is at 9-17.jpg).

Ephraim Taranto’s Family Remaining in Izmir

Dowry records from the Izmir Rabbinate, housed at the CAHJP, identify wives for two of Behor Ephraim's younger brothers. In January 1854, Moshe Taranto wed Sarota Rebi (Ribi), daughter of Avraham and granddaughter of Raphael Rebi, in the Algaze Synagogue. Izmir. Brother Eliezer Taranto married twice - to Joia Sasson, daughter of Eliah, on March 29, 1858 in the Algaze Synagogue (photos at left and above), and to Sarota (Caden) ha-Levy, daughter of Avraham, son of Rabbi Tchelibi Moshe ha-Levy, on 5 June 1868 in Melamen (presumably Menemen, near Izmir). Eliezer's daughter Leah Taranto wed Moshe's son Chelibi (Celebi) Rafael Taranto on January 4, 1895, in Menemen.34

The second of five Taranto brothers, Bension’s uncle, David (b. circa 1827), may be the same as David Taranto who died in summer 1861 (15 Av 5621), survived by his widow Caden Sultana, and was buried on Jerusalem’s ancient Mount of Olives.35 For the youngest of the five brothers, Haim Taranto (b. ca 1836), there are at least two Taranto families descended from a Haim Taranto of Izmir who was born around that same time. One family descends from Marco (Mordechai) Taranto of Izmir, born ca 1865-66 or in 1874, son of a Haim Taranto. Marrying Sarah (Simchula) Carasso of Salonica in the United States around 1907, Marco died in Clairmont, New Jersey, in 1916. DNA test results for Marco’s great-grandson Irwin Taranto establish that Marco’s father Haim was part of our Taranto family.

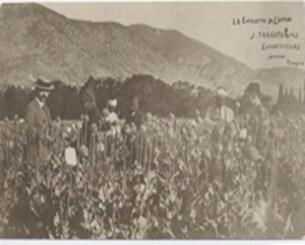

Tarantos in the Lawful Opium Trade

Opium Picking, J. Taranto & Fils,

Exportateurs, Smyrna

While Bension, or his father Behor Ephraim (b. ca 1825), might have engaged in fez-making, and Ephraim's Uncle Yomtov was a banker, some Tarantos in Izmir were inspectors for the lawful and lucrative Dutch opium trade from the early 1800s to 1931, including members of our Taranto family. “During the first half of the 19th century,” the examiners “were Bochor Taranto (d. 1844) and Ishak Abulafia, assisted by Bochor's son Nissim and Haim Gabay.”36 As public examiners for purchasers, they checked opium for color, appearance, weight and scent, and sorted it by quality.37 The drug apparently enjoyed a global distribution since in 1836, Bochor Taranto reported sales to England and the United States.38 In 1885, recreational use of opium was outlawed and retail sale was authorized only upon a doctor's prescription.

Clock Tower, Izmir

A published overview of the Taranto surname includes a page from a 1920s directory listing opium merchants J. Taranto & Fils (photo), and Nissim Taranto.39 From personal communications and published accounts, I learned that the Taranto, Bonomo and Barki families held opium trade concessions. The Bonomo association is of special interest as our ancestor Leah Capouya was the granddaughter of Sinyoru Bonomo of Izmir, whose husband Haham Yehuda (Giuda/Leon) Crespin had a sister Joya (Coya/Joia) wed Behor Haim Moshe Taranto (b. 1817), a second cousin to Bension’s father. Joya and Haim Moshe’s sons Nissim Izkhak Taranto (1852-1932) of Istanbul and Yeoshua (Joshua/Yeshua) Taranto (b. 1847-48, d. 1931) of Izmir also participated in the opium trade.

Tomb of Leon Taranto family,

cemetery in Paris

Interrupted by the First World War, the Dutch opium trade in Izmir continued to decline with the Ottoman Empire’s collapse, the post-war allied occupation of Izmir, the Great Fire that ravaged the city in 1922, and the rise of the Turkish Republic in 1923. Much of this trade shifted to Istanbul.40 In 1926, the J. Taranto & Fils firm remained involved in opium trade.41 A 1926 French publication in Turkey lists T. Taranto et Fils as one of the seven courtiers of opium in Smyrne (Izmir).42 Around 1929, Leon and Richard Taranto, reportedly brothers of Istanbul merchant Nissim Taranto but actually his sons, operated opium processing factories in Istanbul.

Nissim, of our Taranto family, is identified as a cloth, mohair and opium dealer since 1897. Most opiates were shipped to the United States. Operations apparently shut down in 1931, when Turkey signed an international Convention restricting narcotics production and export, and arrested Nissim after seizing a cache of morphine and heroin.43

Taranto Merchants, Diplomats, Attorneys, Physicians and Community Leaders in Turkey

Jewish historian and Turkish Senator, Avram Galante, in his landmark history of the Jews of Turkey, identifies many Tarantos, virtually all from Izmir and Istanbul. They were merchants, physicians, attorneys, police agents, commercial house operators, and Jewish community council members.44 We know most were our Taranto kin, including several important merchants and community leaders. Also, our cousin Roland Taranto and ETSI publisher Laurence Abensur-Hazan have identified additional Tarantos, especially in Izmir, in the Alliance Israélite Universelle archives in Paris. The 19th century Bulletin de l’Alliance Israélite Universelle (online at http://jic.tau.ac.il) has multiple Taranto entries – in July 1864 for David Taranto; in July 1865 for David, Jacob Taranto, Jomtov and N. (Nissim?) Taranto, all of Smyrne (Izmir); in January 1885 for David, Behor and Moise Taranto, Mardochée de Behor Taranto, Abraham de Bension Tarento, and David Toranto, all of Smyrne; and in January 1887, for Behor-Isaac, Eliezer and Moise Taranto, all of Menemen (near Izmir).

Several Tarantos are mentioned in Baruh Pinto’s book on Jewish families in Turkey, What's Behind A Name, Gozelem, Gazetecilik Basin ve Yamin A.S., Istanbul 2002, pp. 165, 176, 191-92, 413, 462, 468, 472, 474-75, 481-82, and other texts. Of special interest is our distant cousin Leon Taranto of Istanbul, who lived from the 1880s to about 1965-68.45 Our late cousin in Tel-Aviv, Joshua (Jo) Taranto, recalled him as Leon Taranto Turaslan. (Aslan is Turkish for Leon.) Leon, a 20th century Istanbul merchant, was the son of Nissim Taranto, and a great-grandson to our family’s Haim Moshe Taranto, b. circa 1772. Leon undertook an urgent diplomatic effort in Salonika involving a British proposal for a separate peace with Ottoman Turkey as the First World War began, with the Turks keeping the straits open to allied vessels. Isaac Taranto, a 20th century legal advisor in Istanbul to the Ottoman Ministry of Foreign Affairs and husband to Leon’s sister Judith Taranto, facilitated his relative’s contact with Ottoman authorities on the British proposal in Salonika.

Adding to Pinto’s summary, Ferod Ahmad writes:

Given this conformity of views, members of the Jewish elite represented Unionist46 policy at home and abroad and were entrusted with sensitive missions. Thus in January 1915, Leon Taranto, a relative of Isaac Taranto, legal counselor at the Foreign Ministry, was sent to neutral Greece to make contact with the British to explore the possibility of a separate peace.47

Tarantos of Atlanta visiting Istanbul Tarantos

As diplomatic efforts failed, war raged between Britain and Turkey, with the British attacking Galipoli in a futile attempt to seize the straits. As the war ended, the Ottoman Empire collapsed. The Turkish Republic was born as its successor, while in 1919-22 the Western allies and Greeks sought to dismember post-war Turkey. Around this time, in 1919-20, Leon Taranto of Istanbul made two business trips to New York, joined on the second by his wife Laura (Lauré) Varon;48 he later returned to Istanbul where he lived out his life. Even before the war, in 1910, Lauré Taranto headed a Jewish welfare society in Istanbul. In post-war Istanbul, Leon Taranto gained prominence as a merchant, taking over his father Nissim’s business. Leon’s ventures included the lawful opium trade, and textile mills. Ultimately, the opium trade succumbed to increasing legal restrictions, and Leon was forced around 1943 to sell his portion of the mill to his Turkish partner, Bezmen, for a ridiculously low price to raise money to pay the confiscatory Varlik Vergisi capitalization tax that the Turkish Republic imposed on Jews, Greeks and Armenians during World War Two.49 After the war, Leon sued Bezmen in a failed attempt to regain his property, but resumed business operations and rebuilt much of his wealth.

Pinto’s book also mentions several persons named Isaac or Izak Taranto; two might be the same. He refers to (1) Dr. Isaac Taranto, a physician for the prisons in nineteenth century Istanbul; (2) Isaac Taranto, an Istanbul attorney who in 1887 headed a Jewish welfare society, and in 1919 founded the Agudat Bene Israel welfare society in Istanbul; and (3) Izak Taranto, mid-twentieth century Istanbul lawyer and President of Or ha Haim Hospital.50 In her biography of Haim Nahum, last Grand Rabbi of the Ottoman Empire and presiding rabbi for the Jews of Egypt until the 1960s, historian Esther Benbassa writes of Nahum’s interaction with lawyer Isaac Taranto in post-war Turkey in 1919, and later in New York. In a January 24, 1921 letter from New York, Rabbi Nahum writes: “My first concern immediately on arrival was to find an office to work in. Monsieur Taranto, who has a very luxurious office in the center of town, where the major administrative offices, banks, and business firms are situated, has been so kind as to put a room at my disposal where I can receive visitors.”51

Tarantos in the Archives for Izmir, and Spreading Globally From Turkey

Recurrent fires and earthquakes have plagued Izmir since the 1600s, destroying most of its archives. The great conflagration erupting in 1922 was particularly destructive, as Greek residents fled the city to escape advancing Turkish armies. While that fire likely destroyed much physical evidence of our family history in Izmir, like the great fire of 1841, some important archival materials are preserved in Israel and Turkey.52

From such records, we can identify 40 Taranto brides and grooms who married in Izmir in the late 1800s and early 1900s,53 and quite a few Izmirli Tarantos protected as European nationals by their consulates in Izmir. This includes three Taranto women (Mazaltol b. 1869 Smirne, daughter of Haim Taranto and Donna Enriquez, wed to Samuele Koen Chemsi; and sisters Vittoria b. 1874 and Fortunata b. 1889, daughters of Josua/Giosue Taranto and Grazia Ciaves, wed to Isacco Aboaf; and Moise Casana, respectively, all born in Smirne), plus children of Taranto mothers (Naftali Gabbai b. 1854, son of Ester Taranto; Moise Cesana b. 1885 Canae, son of Luna Taranto; Samuele Alazraki b. 1859 Smirne, son of Ber Lissa Taranto) registered with the Italian consulate in the 1800s, two individuals registered with the Dutch consulate whose mothers were Tarantos (Bension Ciaves b. 1892 Smyrna, daughter of Sarota Taranto; and Esther Benadova Soria b. 1893 Menemen, daughter of Judith Taranto), and one French protégé in 19th century Izmir.54 Some Tarantos registered with the Italian consulate were cousins to our Leon Bension Taranto. In at least one instance for our Tarantos, the consulate register identifies Livorno, Italy, as the family place of origin. We can also identify dozens of Tarantos buried in Izmir in the last 130 years, and parents of most buried after the 1920s. This fascinating body of material has helped link us to other Taranto branches.

Some Tarantos, our cousins, remain in Izmir and Istanbul.55 In the past century, Taranto descendants settled in six continents. From 19th century Izmir, our Tarantos spread across the globe in the 20th, to Istanbul, Israel, Egypt, Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, Greece, Egypt, Burundi, Congo, South Africa, Venezuela, Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, Canada, and the United States. Other Taranto branches from Izmir have settled also in Uruguay and Australia, carrying Tarantos to six continents and 24 countries.56

As a result of the early 1920s strife in Izmir – the Greek occupation, Turkish recapture, and great fire of 1922 – Jewish emigration from Izmir accelerated. Popular destinations were France and Western Europe. In 1917, while Ottoman Turkey was at war with the Western allies, our cousin Salvador Taranto was born in Geneva, neutral Switzerland. Living in Marseilles when France capitulated to Hitler, Salvador realized that remaining there would be too dangerous. The German army occupied Marseilles by November 1942, and Salvador made plans to leave the next month for Turkey, where he held citizenship, before the Nazis began deporting Jews from Marseilles. Since the collaborationist Vichy regime was only too willing to ‘rid’ itself of its Jews, the fascist French officials granted Salvador’s request for an exit visa, provided he leave within the next three to four days. As passenger ships would not depart for Istanbul until after the deadline, Salvador embarked on a perilous journey by train, across fascist Italy, the Nazi puppet state of Croatia, and a German occupation zone. To obtain the necessary transit visa from the German Consulate, he had to falsify his mother name as Aisha, a Turkish Moslem name, and not Rebecca, which would have revealed his Jewish identity. The deception succeeded; at one point he even obtained lodging from a Nazi officer sporting a swastika armband, and ate in a mess hall with Hitler’s portrait staring down at him. Finally arriving in Turkey, he was arrested on a charge of dodging military service. Salvador enlisted, served a three-year term, and settled in Istanbul, living out his life until age 89 in early 2006.57

Israeli cousin Joshua (Jo) Taranto, born in Izmir in 1922, also moved to pre-war France. In March 1943, two months after Salvador’s escape, Joshua and with two of his sisters, with their parents Leon (Sakally) Taranto and Victoria (Viktorya) Gatenio (Gattegno), followed a similarly perilous route across the German-controlled Balkans to safety in Turkey. He died in Israel, where his daughter Nitza Maor lives today. Cousin Roland Taranto, only age five when France fell, remained in Paris with his parents Nissim Taranto and Suzanne Albagli, who emigrated from the Izmir area in 1922, and miraculously escaped deportation. Now, over 70 years later, Paris remains his home. Other Taranto contacts include cousins (two families) in Izmir, at least four families in Istanbul (some from Izmir), and Izmirli Tarantos in Israel, France, Switzerland, Venezuela, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Australia, Canada, California, Minnesota, and New York.

This is the first part of a three-part series on Sephardic Horizons. Part two. Part three.

Photos & Images

- Leon Bension Taranto and wife Leah Capouya with sons Al, Morris and Ephraim Taranto (standing); and son Joe Toranto and grandson Alan Taranto seated, circa 1950

- Rhodes harbor and stag with Hebrew inscription “Rodos,” cover of 1930s Hebrew-Italian folder travel map for Rhodes

- Harbor of walled city of Rhodes, with stag in foreground, photograph by Leon B. Taranto, 1981

- Ephraim Taranto and Behora Perla Beresit family chart

- Asansör (elevator) building in Izmir’s Karataş quarter, built in 1907 as a public service work of Nesim Levi Bayraklıoğlu, wealthy Jewish banker and trader, for passage from Karataş’ narrow coastline to the hillside of the steep cliff separating the Jewish quarter’s two parts - photograph by Sonja (Bilé) and Hans Vansteenkiste

- Isaac Taranto and Rebecca Soriano family chart

- Diploma of Rabbi Michael (Michel) Albagli de Behor, Rabbinical Seminary of Rhodes, 1934, photograph from Rhodes Jewish Museum www.rhodesjewishmuseum.org

- Realty transaction and title history, Feb. 1862 (Adar I 5622), Smyrna, for El Kortijo de Katan yard in Ergat Bazar, purchased Oct. 18, 1817 (8 Heshvan 5578) by ‘guevir’ (rich) brothers Haim Moshe Taranto and Efraim Taranto, copy obtained by Rabbi Dov Cohen from CAHJP, Jerusalem

- Harbor view of Smyrna (Izmir), late 1800’s, collection of Leon B. Taranto

- View of Coastline of Smyrna (Izmir) and the Quarantine, late 1800’s, collection of Leon B. Taranto

- Entrance to Yom Tov Taranto synagogue in Ohel Moshe, Jerusalem, founded 1890, photograph by Momy Benouaich, 2003

- Eulogy to Haham Tchelibi Itzhak Taranto

- Taranto family tree, earliest 4 generations, with brothers Haim Moshe Taranto and Efraim Taranto of Smyrna late 1700s to mid-1900s, their parents, and their children and grandchildren

- Ergat Bazaar (Irgatpazari), Izmir, photo by Sonja (Bilé) and Hans Vansteenkiste

- Square of the Jewish Martyrs, Jewish quarter of Rhodes, sea horse fountain, 1981

- Holy Ark, Algaze synagogue, Izmir, photo by Sonja (Bilé) and Hans Vansteenkiste

- Algaze synagogue, Izmir, photo from Juhasz (Esther), ed., Sephardi Jews of the Ottoman Empire: Aspects of Material Culture, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem Publishing House, Jerusalem, 1990

- Cueillette de l’opium [picking of opium], J. Taranto & Fils, Exportateurs, Smyrne, Turquie

- Paris cemetery monument to Leon Taranto (aka Leon Taranto Turaslan) of Istanbul, photo by Fulvio Papouchado

- Alan Taranto family visiting in Istanbul with cousins, Erol Taranto family

Select References

Books:

Laurence Abensur-Hazan, Smyrne: Evocation d’une Echelle du Levant – XIV-XX Siecles, Editiones Alain Sutton, Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire, France, 2004

Elkan Nathan Adler, Jewish Travelers (1930), republished as Jewish Travelers in the Middle Ages - 19 Firsthand Accounts, Dover Publications, New York, 1987

Feroz Ahmad, “The Special Relationship: The Committee of Union and Progress and the Ottoman Jewish Political Elite, 1908-1918,” pp. 212-30 in Jews, Turks, Ottoman: A Shared History, Fifteenth Through the Twentieth Century, ed. Avigdor Levy, Syracuse Univ. Press, 2002, p. 230

Marc D. Angel, The Jews of Rhodes: The History of a Sephardic Community, Sepher-Hermon Press, New York, 1978

Marc D. Angel, ed., Studies in Sephardic Culture - The David N. Barocas Memorial Volume, Sepher-Hermon Press, New York, 1980

Rifat N. Bali, The Varlik Vergisi Affair A Study on Its Legacy - Selected Documents, The Isis Press, Istanbul, 2005. www.theisispress.org/search.asp?search=2005&Submit=Go

Baruch Habanim, vol. II, parag. 52, Izmir 1868

Shelomo Ben-Aderet, Hidushei Nida, Altona, 1737

Isaac Benatar, Rhodes and the Holocaust: The Story of the Jewish Community from the Mediterranean Island of Rhodes, iUniverse Inc., Bloomington, 2010

Esther Benbassa, Haim Nahum: A Sephardic Chief Rabbi in Politics, 1892-1923, Univ. of Alabama Press (Tuscaloosa and London), 1995, pp. 177-78, 183.

Esther Benbassa and Aron Rodrigue, eds., A Sephardi Life in Southeastern Europe - The Autobiography and Journal of Gabriel Arie, 1863-1939, Univ. of Washington Press, Seattle, 1998

Haim Beinart, Atlas of Medieval Jewish History, Carta, The Israel Map Publishing Co., Ltd., 1992

Miriam Bodian, Hebrews of the Portuguese Nation: Conversos and Community in Early Modern Amsterdam, Indiana Univ. Press, Bloomington, 1997

Pere Bonnin, Sangre Judia, Flor del Viento Ediciones, Spain 1998

James Carroll, The Sword of Constantine: The Church and the Jews - A History, Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston and New York, 2001

Miriam Cohen and Jo Anne Rousso, eds., Congregation Etz Ahayem, Tree of Life, 1912-1982, Montgomery, Alabama, 1982

Em Habanim, vol. II, parag. 52, Izmir 1881

Encyclopedie Biographique de Turquie - Who is Who in Turkey - III - Stamboul 1930-32 - Hamit Matbaasi (Mehmet Zeki, Turkiye Teracimi Ahval - Ansiklopedisi - III - Istanbul 1930-32: photograph and entry for Mordechai Taranto (b. 16 Dec. 1859, Smyrne), M & J. Taranto, negociant (merchant) de Smyrne (Izmir) et fils de (son of) Moise Taranto, at p. 528

Guilherme Faiguenboim, Paulo Valadares, and Anna Rosa Campagnanao, Dicionario Sefaradi de Sobrenomes – Dictionary of Sephardic Surnames, Editora Fraiha, Rio de Janeiro, 2003

Hizkia M. Franco, The Jewish Martyrs of Rhodes and Cos, Harper Collins Publishers, Harare, Zimbabwe, 1994

Benjamin R. Gampel, "The Exiles of 1492 in the Kingdom of Navarre: A Biographical Perspective," pp. 104-117 in Crisis and Creativity in the Sephardic World: 1391-1648, Benjamin R. Gampel, ed., Columbia Univ. Press, New York, 1997

Benjamin R. Gampel, The Last Jews on Iberian Soil - Navarrese Jewry 1479-1498, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989

Martin Gilbert, Jewish Historical Atlas, Collier Books, New York, 1969

Noah Gordon, The Last Jew, St. Martin's Press, New York, 2000

Guide for Bene Brith Loge de Constantinople (No. 678), 1931, pp. 193-95: entries for Nissim Taranto, négociant (merchant), Istanbul, 1911, reg. no. 11; Isaac de Taranto, docteur (doctor), 1915, reg. no. 89; Mossé de Taranto, négociant (merchant), Mossé Taranto & Cie, 1915, reg. no. 373

Eliahu Ha-Cohen, Yelo Od Ela, Izmir, 1853

Haim David Hazan, Ishrei Lev, Izmir, 1869

The Jewish Encyclopedia - A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day, Funk & Wagnalls, 1901-05, vols. 1, 9, 10, 12

Mattis Kantor, The Jewish Timeline Encyclopedia - A Year-By-Year History From Creation To The Present, Jason Aronson, Inc., Northvale, NJ, 1992

Michael M. Laskier, The Jews of Egypt: 1920-1970, New York Univ. Press, 1992

Beatrice Leroy, The Jews of Navarre in the Late Middle Ages, The Magnes Press, Hebrew University: Jerusalem, Hispania Judaica Series vol. 4, 1985

Avner Levi, "Shavat Aniim: Social Cleavage, Class War and Leadership in the Sephardi Community - The Case of Izmir 1847," pp. 184-202 in Ottoman and Turkish Jewry - Community and Leadership, ed. Aron Rodrigue, Indiana University Turkish Studies, 1992

Isaac Jack Levy, Jewish Rhodes: A Lost Culture, Judah L. Magnes Museum, Berkeley, 1989

Rebecca Amato Levy, I Remember Rhodes, Sepher-Hermon Press, New York, 1987

Marvin Lowenthal, A World Passed By - Great Cities in Jewish Diaspora History, Harper & Bros., New York, 1933, republished, Joseph Simon, ed., Pangloss Press, 1990

Menoras Hamaor: The Weekday Festivals – Rosh Chodesh – Chanukah – Purim – An Annotated Excerpt, translated by Rabbi Yaakov Yosef Reinman, C.I.S. Publication Div., Lakewood, NJ, 1986

Philip Mansel, Constantinople - City of the World’s Desire: 1453-1924, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1996

Nissim Moshe Modai, Derisha Mehaim, Izmir, 1888

Montgomery City Directories, 1910-13

Susan W. Morgenstein and Ruth E. Levine, The Jews in the Age of Rembrandt, the Judaic Museum of the Jewish Community Center of Greater Washington, Rockville, 1981

Robin R. Mundill, England’s Jewish Solution: Experiment and Expulsion, 1262-1290, Cambridge Univ. Press, 1998

Nahalaot belev haIr: lesayer im yad ben Zvi [Neighborhoods in the heart of the city: Touring with Yad Ben Zvi] published by Yad Ben Zvi (Ben Zvi Institute), Jerusalem 2000

Baruh Pinto, The Sephardic Onomasticon, Gozelem, Gazetecilik Basin ve Yayin A.S., Istanbul, 2004

Baruh Pinto, What's Behind A Name, Gozelem, Gazetecilik Basin ve Yamin A.S., Istanbul, 2002

Joshua Eli Plaut, Greek Jewry in the Twentieth Century, 1913-1983: Patterns of Jewish Survival in the Greek Provinces Before and After the Holocaust, Associated University Press, 1996

Ruth Porter and Sarah Hare-Hoshen, Odyssey of the Exiles - The Sephardi Jews 1492-1992, Beth Hatefutsoth and Ministry of Defence Publishing House, 1992

Brian Pullan, The Jews of Europe and the Inquisition of Venice, 1550-1670, Barnes & Noble, and Blackwell Publishers, 1997, pp. 210, 227

Moise Rahmani, Rhodes un Pan de Notre Mémoire, Editions Romillat, Paris, 2000

Jean Régné, History of the Jews in Aragon: regesta and documents, 1213-1327, Hispania Judaica, v.1, Jerusalem: Magnes Press, Hebrew Univ., 1978 (index compiled by Mathilde Tagger at www.sephardicgen.com/databases/databases.html )

Aron Rodrigue, French Jews, Turkish Jews: The Alliance Israélite Universelle and the Politics of Jewish Schooling in Turkey, 1860-1925, Indiana Univ. Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1990

John and Elizabeth Romer, The Seven Wonders of the World - A History of the Modern Imagination, Henry Holt & Co., New York, 1995

Cecil Roth, History of the Jews in Venice, Schocken Books, New York, 1975

Minna Rozen, "Strangers in a Strange Land: The Extraterritorial Status of Jews in Italy and the Ottoman Empire in the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Centuries," in Ottoman and Turkish Jewry: Community and Leadership, Aron Rodrique, ed., Indiana Univ. Turkish Studies, Bloomington 1992

Howard Sachar, Farewell Espana - The World of the Sephardim Remembered, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1994

Jan Schmidt, From Anatolia to Indonesia - Opium trade and the Dutch community of Izmir, 1820-1940, Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut; Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten [distri.], Uitgaven van het Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul, ISSN 0926-9568;82, Leiden, Nederland, 1998

Stanford J. Shaw, History of the Jews of the Ottoman Empire and Turkish Republic, New York Univ. Press, New York, 1991

Sonja Bilé Vansteenkiste, Grootvader Leon Bilé, zijn & mijn geschiedeis (Granddad Leon Bilé, his story and my story), Blankenberge, Belgium, 2010

Yado Bakol, Izmir, 1867

Zaorei (Zahore) Hama, Salonica, 1738

Journal Articles:

Laurence Abensur-Hazan, “How To Research Families From Turkey And Salonika,” Avotaynu, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 28-30, 1998

Susan M. Adams, et al, "The Genetic Legacy of Religious Diversity and Intolerance: Paternal Lineages of Christians, Jews and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula," Amer. J. Human Genetics, 2008, vol. 83, pp. 725-36

R. Bedford, "Brief Overview of the Taranto Family Name," Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture, New York, 1996

Meir Benayahu, “Hatena Hashbetait Besaloniki” (the Sabbatean Movement in Salonica)

Alain Farhi, “Preliminary Results of Sephardic DNA Testing,” Avotaynu, vol. 23, no. 2, p. 9, 2007

Leyla Ipeker, "A Research on Names and Surnames," Mosaic: Genealogy Research on the Jews of Turkey, no. 1, The Roots Committee, Istanbul 1996

Leyla Ipeker, “Turkey,” Avotaynu, vol. 12, issue no. 3, Spring 1997, pp. 55-57

Stella Kent, "The Blend of Turkish Jews," Mosaic: Genealogy Research on the Jews of Turkey, no. 1, The Roots Committee, Istanbul 1996

Yitzchak Kerem, “The Settlement of Rhodian and Other Sephardic Jews in Montgomery and Atlanta in the Twentieth Century,” Amer. Jewish Hist., Dec. 1997, pp. 373-91. www.sephardicstudies.org/atlanta.html

V. Rodriguez, "Genetic Sub-structure in Western Mediterranean Populations Revealed by 12-Chromosome STR Loci," Internat’l J. Legal Med., 2009, vol. 123, pp 137-41

Shaul, “Summary of a Recent Lecture: Tracing the Family from Izmir (Smyrna) and Yugoslavia to Eretz Israel,” Sharsheret Hadorot, vol. 5, no. 3, part II, Israel Genealogical Society: Jerusalem, Oct. 1991

Leon Taranto, "Izmir and Rhodes: Taranto Family Origins, Archives, and Links to other Sephardim," ETSI - Revue de Genéalogie et d'Histoire Sépharades (Sephardi Genealogical and Historical Review), vol. 15, pp. 3-9, Dec. 2001

Leon B. Taranto, "Ottoman Empire Sephardim: Historical Migrations and Genealogical Resources " and "Consolidated List of References and Recommended Publications," Sharsheret Hadorot - Journal of Jewish Genealogy, vol. 14, nos. 2-3, Israel Genealogical Society, Fall 1999 and Winter 2000

Leon B. Taranto, “The Israel Family – A Rabbinical Family 1670-1932,” La Lettre Sépharade, vol. 20, 2005

Leon Taranto, “History and Genealogy of the Jews of Rhodes and Their Diaspora,” Avotaynu, vol. 25, no. 1, 2009

Leon B. Taranto, “Sources for Ottoman Sephardic Genealogy: Turkey and Rhodes,” Avotaynu, vol. 21, no. 3, 2005

Roland Taranto, "Les Nomes de Famille Juifs de Smyrne," ETSI - Revue de Généalogie et d'Histoire Séfarades, vol. 5, no. 16, pp. 3-9, Mar. 2002

Sonja Bilé Vansteenkiste, “La Révélation Extraordinarie de Mes Racines Juives Séfarades d”Izmir,” ETSI - Revue de Genéalogie et d'Histoire Sépharades, vol. 11, no. 43, Paris

Newspapers:

Andreé Brooks, “In Italian Dust, Signs of a Past Jewish Life,” New York Times, 15 May 2003

Yuval Azoulay, “Captain Taranto had Decided to Reenlist to Fill the Shoes of his Dead Friend,” Haaretz International, 30 Nov. 2004 www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/507726.html

“Commander Killed in Tunnel Collapse Laid to Rest, Jerusalem Post, 1 Dec. 2004. www.jpost.com (25 Dec. 2004)

Margot Dudkevitch, “IDF Officer Killed in Tunnel Collapse in Southern Gaza,” Haaretz – Israel News, 30 Nov. 2004

Yair Ettinger, “Reunion of Tears,” Haaretz, 3 Dec. 2004. www.haaretz.com

“Funeral Notice of Mrs. Leah Taranto,” Atlanta Constitution, July 29, 1950, p. 14

“Girl, 22, Dies at Grady After Drinking Poison,” Atlanta Constitution, March 4, 1933, p. 1

“IDF Officer Killed in Tunnel Collapse in Southern Gaza,” Daily News from Israel, Daily Alert prepared for Parents of Major American Jewish Organizations, 30 Nov. 2004 www.solidaritywithisrael.org

“Leon Taranto, 92, Dies; Rites Today,” Atlanta Constitution, May 2, 1950, p. 22

“Mrs. Taranto’s Rites Sunday,” Atlanta Journal, July 29, 1950, p. 9

Obituary of “Leon Benson Taranto,” Atlanta Journal, May 2, 1950, p. 33

James Taranto, “He Didn’t Say Uncle – But Salvador Taranto Lived To Be One,” Wall Street Journal, 20 Jan. 2006 www.opinionjournal.com/taste/?id=110007840

Vital Records, U.S. National Archives:

Entry for Leah Capouya Taranto and Children, National Archives Microfilm Publication T-715, roll ___, Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, 1897-1942, from July 13, 1911 to ___, vol. 4318, p. 31, lines 11 et seq.

Entry for Ephraim Taranto, April 21, 1910, Bureau of the Census, Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910 Population, State of Alabama, City of Montgomery, Enumeration District No. 89

U.S. Census Records, 1920, State of Georgia, City of Atlanta

U.S Dept. of Labor, Naturalization Service, Declaration of Intention of Abraham Taranto, No. 2237, United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia (Atlanta), April 13, 1925

U.S Dept. of Labor, Naturalization Service, Declaration of Intention of Ephraim Taranto, No. 2342, United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia (Atlanta), June 2, 1926

Foreign Archives:

Alliance Israélite Universelle, Paris; Bulletin de l’Alliance Israélite Universelle http://jic.tau.ac.il

Ben Zvi Institute (Yad Ben-Avi), Jerusalem http://ybz.org.il/

Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, Jerusalem http://sites.huji.ac.il/archives/

Rhodes Jewish Community office, Rhodes, Greece

Unpublished manuscripts:

Capouya family histories provided by Dr. Morris Nace Capouya and Melvyn Halfon, 1997

Dov Cohen, Izmir - List of 7300 Names of Jewish Brides and Grooms Who Were Married in Izmir Between the Years 1883-1901 & 1918-1933, List No. 1, Summer 1997 – 5757

Internet:

Altona http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Altona,_Hamburg

Bibliography of Meir Benayahu’s publications, in Hebrew, link at: http://manuscriptboy.blogspot.com/2009/07/meir-benayahu-bibliography.html

Casa-Shalom: The Institute of Marrano-Anusim Studies www.casa-shalom.com/ has extensively studied, and written and lectured about, the crypto-Jews of Ibiza.

Ellis Island passenger arrivals – Port of New York, American Family Immigrant Family Center, listed at: www.ellisislandrecords.org

Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, www.israel-mfa.gov.il/MFA/MFA%20Publications/Photo%20Exhibits/Jerusalem-%20Capital%20of%20Israel-%20%20A%20Collage%20of%20Neighb

Istanbul Jewish Genealogical Records www.sephardiccouncil.org/istanbul/

Jewish History Sourcebook: The Expulsion from Spain, 1492 C.E. www.fordham.edu/halsall/jewish/1492-jews-spain1.html

Yitzchak Kerem, “The Settlement of Rhodian and Other Sephardic Jews in Montgomery and Atlanta in the Twentieth Century,” Amer. Jewish History, Dec. 1997, pp. 373-91 www.sephardicstudies.com/atlanta.html

Les Fleurs de l’Orient www.farhi.org

Medieval Sourcebook: Synod of Castilian Jews, 1432 www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1433synod-castile-jews.html

Gloria Mound, “Survivors of the Spanish Exile: The Underground Jews of Ibiza,” Jerusalem Letter of Lasting Interest (10 Feb. 1988) www.jcpa.org/jl/hit12.htm

Rhodes Jewish Museum www.rhodesjewishmuseum.org

Shabbatai Zevi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sabbatai_Zevi

1Leon Taranto is a native of Atlanta and Washington DC attorney who is active in Sephardic genealogy. He is an organizer and planning committee member for Vijitas de Alhad of the Greater Washington DC area. He has authored articles for Sephardic and Jewish genealogical journals on the Jews of the Ottoman Empire and Mediterranean Basin, and presented at international conferences on Jewish genealogy, to genealogical societies, and at synagogue-hosted events.

2 Some sources are archives in Rhodes, Izmir, Israel and the USA; books; journals; newspapers; cemetery stones; and synagogue plaques. Reliability is often difficult to assess even for archival material. Genealogists lament the questionable accuracy of obituaries, naturalization petitions, ship manifests, census records, etc. For example, the January 5, 1920, Census Bureau page for the Taranto household at 222 Central Avenue in Atlanta says “Benseon Taranto” (age 55), his wife Leah (44), their “daughter(s)” “Sadie Cohen” (25) and ”Victoria Taranto” (18), and sons Abraham (14) and Maurice (12), born in Rhodes, immigrated in 1912. But ship manifests show Bension and Sadie arrived in 1911, with conflicting age data. And they had no daughter Victoria, though son Ephraim did marry Victoria Terreno.

3 Surprisingly, the manifest lists his birthplace as Smyrna (Izmir), not Rhodes.

4 Other Rhodeslis on the Laura were Samuel M. Halfon (b. 1885) and Moses Hasson (b. 1888).

5 Henry Aron Cittone, grandson of Albert (A.) Bonomo’s sister Eugenie (Sinyoru) Bonomo, recalls his great-uncle Albert acting as family godfather, receiving relatives from Smyrna (Izmir). Albert operated Bonomo Candies, famous maker of Bonomo Turkish taffy on Coney Island. Ultimately, his elder son Victor sold the business to Tootsies (Tootsie Rolls). Younger son Joe Bonomo gained fame as a bodybuilder and Hollywood stuntman in many silent movies.

6 Two archival sources, from America and Rhodes, suggest that Bension was born as early as 1854 and as late as 1864. The 5 January 1920 entry in the U.S. Census for Atlanta lists 'Benseon Taranto' as age 65, which would date his birth to 1854. A late 1920's census by the Italian government, occupying Rhodes from 1912 through Second World War, lists ‘Bension Taranto,’ born 1864 in ‘Rodi’ (Rhodes) to Efraim and Behora; Bension's wife ‘Behora Capuia,’ born 1871 in Rodi, daughter of ‘Raffaele Capuia’ and ‘Mazaltov Crispin;’ and their children Caden (b. 1899), Abramo (b. 1904), Gioia (b. 1903) (handwritten entry difficult to read), Mosé (b. 1905), and Elisa (b. 1907), all born in 'Rodi.' Caden = Catherine, Abramo = Al, Gioia = Julia, Mosé = Morris, and Elisa = Alice.

7 If a boy, the first-born child was called Behor or Bohor, like Bension's father Ephraim. Bension's mother, Ephraim's wife Behora Perla, was also a first-born.

8 Ephraim and Perla’s gravestones appear at www.rhodesjewishmuseum.org on the cemetery plots link. The Rhodes Jewish Museum is maintained by Aron Hasson, Florine and Jack Hasson’s nephew. As the gravestones show, Behor Raphael Ephraim Taranto died 29 March 1876 (4 Nissan 5636), and his wife Behora Perla died 16 December 1909 (4 Tevet 5670).

9 The gravestone for Behora Bulissa Sara Habib Taranto (d. 1933) is at plot 9-15, beside her husband Nissim Habib at plot 9-16, and her parents Behor Raphael Efraim Taranto and Behora Perla Beresit Taranto (shown as Behora Taranto) at plots 9-17 and 9-18.

10 Hizkia M. Franco, The Jewish Martyrs of Rhodes and Cos, Harper Collins Publishers, Harare, Zimbabwe, 1994; Moise Rahmani, Rhodes un Pan de Notre Mémoire, Editions Romillat, Paris, 2000; Isaac Benatar, Rhodes and the Holocaust: The Story of the Jewish Community from the Mediterranean Island of Rhodes, iUniverse Inc., Bloomington, 2010.

11 It was previously thought Behora had a daughter Rocha (born ca 1879-80), who wed a Soriano (likely Elia or Eliyahu) and gave birth about 1900 to a son, Moise (Maurice). To the contrary, Maurice, who lived on Rhodes until his death in 2002 at age 98, heading the tiny surviving Jewish community, confirmed that his mother was Rocha Levy. But Maurice was related to one branch of our Taranto family. His father Elia's sister Rebecca Soriano wed Isaac Taranto, Bension's younger brother. Elia and Madame Soriano (2) and the Moise Soriano family (4) are six of 54 Rhodian Jews who escaped the 1944 Nazi deportations to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp because they held Turkish or other foreign citizenship. Franco, surpa, The Jewish Martyrs of Rhodes and Cos, p. 74. Their survival resulted from the heroic intervention of the Turkish Consul on Rhodes, Selahattin Ulkumen, who interceded with the Nazi occupiers at great risk to himself and his family. “Honoring the Turkish Rescuers - Keynote Speaker: Bernard Turiel, Survivor,” Holocaust Remembrance 2002, federal inter-agency program at the Lincoln Theater, Washington, DC, April 11, 2002; Baruh Pinto, What's Behind A Name, Gozelem, Gazetecilik Basin ve Yamin A.S., Istanbul 2002, p. 220. Ulkumen was the first Moslem honored as a “Righteous Gentile” at Yad Vashem. After the War, Maurice and his family were among the handful of Jews returning to Rhodes. Rocha lived beyond age 100, to the 1980's. Maurice’s widow and first cousin Victoria (né Soriano) lives on Rhodes with their children, Elio and Rita, now in their 70’s. Maurice's role as President of the remnant of the Jewish Community of Rhodes after the Holocaust is discussed by Joshua Eli Plaut, Greek Jewry in the Twentieth Century, 1913-1983: Patterns of Jewish Survival in the Greek Provinces Before and After the Holocaust, Associated University Press, 1996, pp. 109-110, 199.

12 Much information for Isaac Taranto and family was provided by his grandson Joe Peha of Seattle, and Joe's wife, Esther Menashe Peha, who also shares our descent from Rabbi Moshe Israel (1670-1740) of Rhodes. Joe's mother was Victoria Taranto Peha, Bension’s niece.

13 An early 1930’s photograph in Rebecca Amato Levy's I Remember Rhodes, Sepher-Hermon Press, New York, 1987, depicts schoolteacher Mathilde Taranto and her students in Rhodes.

14 Lucia's November 27, 1937 marriage to David Benyacar was the first wedding in the Kehila Chalom of Buenos Aires, the Congregation for the Rhodeslis emigrés to Argentina.

15 Marc D. Angel, The Jews of Rhodes: The History of a Sephardic Community, Sepher-Hermon Press, New York, 1978, pp. 84-85, 147.

16 Mathilde, a well-known teacher in Rhodes, also worked for high officials of the pre-war Italian government. Moving to Sacramento, she worked for the State of California for many years. Isaac’s widow Rebecca lived out her days in Sacramento, where she is buried. Moving to Seattle, Mathilde taught French, tutored in many foreign languages (e.g., French, Italian, Spanish, Ladino), served the city as an interpreter, and married David J. Behar, Hazan (cantor) for the Ezra Bessaroth Synagogue. Rabbi Marc Angel pays tribute to Rev. Behar in his book. Angel, The Jews of Rhodes, supra, p. 15; p. 178 n.9, n.14, n.20; p. 180 n.41; p. 181 n.4.

17 Alain Farhi, “Preliminary Results of Sephardic DNA Testing,” Avotaynu, vol. 23, no. 2, p. 9, 2007.

18 Moussani’s son Solomon Rousso married Sultana Taranto, Bension and Leah’s daughter. Moussani’s daughter Esther Rousso married Nissim Capouya, Leah’s brother. Moussani’s son Daniel Rousso wed Sarina Capouya, Leah’s first cousin.

19 Goffman, Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550-1650, Univ. of Washington Press, 1990; Odyssey of the Exiles, supra, pp. 96-97; Minna Rozen, “Strangers in a Strange Land: The Extraterritorial Status of Jews in Italy and the Ottoman Empire in the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Centuries,” in Ottoman and Turkish Jewry: Community and Leadership, Aron Rodrique, ed., Indiana Univ. Turkish Studies, Bloomington 1992, pp. 124-28; Esther Benbassa & Aron Rodrigue, Sephardi Jewry: A History of the Judeo-Spanish Community, 14th-20th Centuries, Univ. of Calif. Press, Berkeley & Los Angeles 1993, pp. 10, 23, 46-47, 49.

20 Personal communication from Dov Cohen, Rehov Ahoshen, 18, P.O. Box 11, DN. Shimshon, 99785 - NOF Ayalon, Israel, dkcohen@bezeqint.net. If Isaac and his father were Izmir natives, this would date the Taranto settlement there to at least the early 1700’s.

21 Zinbul, or Zimbul, is the Turkish word for the flower hyacinth.

22 A circa 1895 census record from the CAHJP found by Dov Cohen of the Ben Zvi Institute lists Yomtov as a ‘Sarraf’ or banker/ money-changer, born 1816-17, and son of Efraim Taranto.

23 Rabbi Dov Cohen of Ben-Zvi Institute located the original book and provided a copy of the title page with Itzhak ben Efraim Taranto’s signature. Founded in 1535 as a fishing village outside of Hamburg, Germany, Altona became home to a major Jewish community because of restrictions on Jewish settlement in Hamburg until 1864 and during the last few years of Napoleon’s rule. From 1640 until 1864, Altona was part of Denmark. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Altona,_Hamburg

24 Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, www.israel-mfa.gov.il/MFA/MFA%20Publications/Photo%20Exhibits/Jerusalem-%20Capital%20of%20Israel-%20%20A%20Collage%20of%20Neighb

25 The Taranto Synagogue is located at 18 Agilboa Street, Jerusalem. As of a few years ago, the Gabay of the synagogue was Abraam Cohen, telephone no. 02-5373756.

26 Itzhak Taranto was not a rabbi as we think of one today. Israeli researcher Dov Cohen, who located and translated parts of the referenced CAHJP and Ben Zvi Institute documents, explains that ‘Haham Hashalem’ or ‘complete sage’ was the title for a ‘Talmid Haham,’ one regarded as a rabbi, but without the formal and official functions in the community.

27 Avram Aji of Izmir, whose wife Elsie Barmaimon is a granddaughter of Leon Taranto (1886-1980) of Izmir (son of Bension’s third cousin Yeoshua Taranto), says Ergat Bazar could refer to Irgat Pazari, meaning a place for hiring daily workers, mainly for construction or carrying goods. An Izmir native told me that area is now called Halilrifat Paza, Güzelyali. See www.geziyazilari.net/izmir1.html

28 Yossef Benveniste purchased this yard on 22 Heshvan (1 Nov. 1809) from David Mizrahi and his wife Rivka, as witnessed by Rabbis Beraha Danon and Hiya Pontremoli. Nearby properties of Shelomo Alazraki’s heirs, Loran Belom, Eliyahu ben Moshe, and Rav Shelomo Hakim’s heirs are also identified.

29 Over 50 years later, Rabbi Yehoshua Moshe Mordehay Crespin’s great-granddaughter Leah Capouya wed Leon Bension Taranto, the great-grandson of Efraim Taranto (b. circa 1780).

30 How much was 8,000 araiot worth when the Taranto children sold their interest to mother Sultana in 1847? The 8,000 araiot Sultana paid by equaled one-sixth (1/6th) of the entire budget for Izmir’s Jewish community that year. Community revenues totaled 48,000 ‘arayot,’ deriving from taxes (wine and cheese gabela, head tax) rents, dowries, and a mill. Expenses were 48,500 ‘arayot,’ including such outlays as payments to rabbis and maintenance of the Religious Court (11,300), salaries to gravediggers and bundles for the poor (4,000), salary to a clerk (2,500), servants wages (3,000), Haluka to the Holy Land (3,000), and clothes for the poor (5,000). Avner Levi, “Shavat Aniim: Social Cleavage, Class War and Leadership in the Sephardi Community - The Case of Izmir 1847,” pp. 184-202 in Ottoman and Turkish Jewry - Community and Leadership, ed. Aron Rodrigue, Indiana University Turkish Studies, 1992.

31 The eulogy’s Hebrew text appears in paragraph 52 of Em Habanim, vol. II, published in Izmir, 1881. Bracketed material consists of explanatory notes by Dov Cohen, who located and translated the eulogies.

32 The Hebrew text appears in paragraph 52 of Baruch Habanim, vol. II, published in Izmir, 1868. Explanatory notes by Dov Cohen, who translated the passage, are in brackets.

33 Baruh Pinto, The Sephardic Onomasticon, Gozelem, Gazetecilik Basin ve Yayin A.S., Istanbul, 2004.

34 All dowry records were located and translated by Dov Cohen. Information for the wedding of Leah (Lea) Taranto and Chelibi Rafael Taranto (Bension's first cousins) was provided by their grandson Roland Taranto of Paris, based on records from Dov Cohen.

35 Personal communications from Mathilde Tagger in Jerusalem, referring to a gravestone inscription for David Taranto in the Hebrew book by Asher Leib Brisk, Helkat Mehokek, published in Jerusalem, 1896-1913. As Mathilde explains, the book is a collection of booklets from which the author copied inscriptions for about 8,000 persons from gravestones or death registers.

36 This Bochor Taranto who was part of the opium trade and died in 1844 could have been Haim Moshe (b. ca 1772), elder brother to our ancestor Efraim Taranto (b. ca 1780), Bension’s great-grandfather.

37 Jan Schmidt, From Anatolia to Indonesia - Opium trade and the Dutch community of Izmir, 1820-1940, Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut; Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten [distri.], Uitgaven van het Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul, ISSN 0926-9568;82, Leiden, Nederland, 1998, pp. 35. Laurence Abensur-Hazan, publisher of ETSI - Revue de Genéalogie et d'Histoire Sépharade, kindly directed my attention to this text and the Taranto references.

38 Schmidt, supra, p. 98.

39 R. Bedford, “Brief Overview of the Taranto Family Name,” Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture, New York, 1996.

40 Schmidt, supra, p. 173.

41 Schmidt, supra, p. 174.

42 Laurence Abensur-Hazan, Smyrne: Evocation d’une Echelle du Levant – XIV-XX Siecles, Editiones Alain Sutton, Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire, France, 2004, p. 80.

43 Schmidt, supra, p. 176.

44 Avram Galante, Histoire des Juifs de Turquie, Reprint, Isis Press, Istanbul 1991, vols. 1 (pp. 200, 207-08, 335, 337-38), 2 (pp. 97, 265-69), 3 (pp. 20, 46, 100-01), 4 (pp. 10, 326), 8 (pp. 22-23), and 9 (p. 106).

45 Only a brief summary about Leon Taranto of Istanbul appears here. I gleaned much information from Pinto’s book; Ellis Island passenger arrival records for Leon, age 31, and his wife Laura Varon, age 25, on arrival in New York for a visit in 1920; 1912 Istanbul marriage record for Leon and Laura in the Istanbul Jewish Genealogy Project database www.sephardiccouncil.org/istanbul/ (now offline), which Dan Kazez coordinated and the International Sephardic Leadership Council hosted; communications with our late cousins Salvador Taranto of Istanbul and Joshua (Jo) Taranto in Tel-Aviv (formerly of Izmir), and others, particularly historian Rifat Bali of Istanbul, and Henry Cittone; several Turkish legal manuscripts from the 1950’s that Bali provided (and our Israel family cousin Lily Arditi summarized for me) on the Taranto-Bezmen lawsuit – Leon Taranto’s unsuccessful efforts in the early 1950s to regain a mill business he was forced to sell for cents on the dollar to his Turkish partner Bezmen to pay the Varlik Vergisi capitalization tax that the Turkish government imposed on Jews and other minorities during World War Two, essentially confiscating most of their property and imposing forced labor on many.

46 “Unionist” refers to the Committee of Union and Progress, the political movement of the Young Turks that sought to liberalize and modernize Ottoman Turkey in its last years, extend political rights to Jews and other minorities, and foster Turkish nationalism.

47 Feroz Ahmad, “The Special Relationship: The Committee of Union and Progress and the Ottoman Jewish Political Elite, 1908-1918,” pp. 212-30 in Jews, Turks, Ottoman: A Shared History, Fifteenth Through the Twentieth Century, ed. Avigdor Levy, Syracuse Univ. Press, 2002, p. 230

48 Ship manifests for vessels aboard which Leon Taranto and his wife Laure arrived at the Port of New York are available online at the American Family Immigration History Center, Ellis Island Passenger Arrivals. www.ellisislandrecords.org The 1920 manifest identifies Laure Varon Taranto, age 25, as the wife of Léon Taranto, age 31, both born in Constantinople.

49 The Varlik Vergisi capitalization tax exceeded one’s annual income. Jews and other minorities unable to pay were deported to forced labor camps. Although the harsh tax and labor camps were a temporary measure, it so shook the Jewish community that most emigrated in the two decades after the war, primarily to Israel. Rifat N. Bali s chronicles the experience of the Turkish Jewish community during the Varlik Vergisi and the war years in his book, The Varlik Vergisi Affair A Study on Its Legacy - Selected Documents, The Isis Press, Istanbul, 2005. www.theisispress.org/search.asp?search=2005&Submit=Go

50 See also Guide for Bene Brith Loge de Constantinople (No. 678), 1931, pp. 193-95: négociants (merchants) Nissim Taranto, Istanbul, 1911, Mossé de Taranto, 1915; Dr. Isaac de Taranto, 1915.

51 Esther Benbassa, Haim Nahum: A Sephardic Chief Rabbi in Politics, 1892-1923, Univ. of Alabama Press (Tuscaloosa and London), 1995, pp. 177-78, 183.

52 Laurence Abensur-Hazan, “How To Research Families From Turkey And Salonika,” Avotaynu, vol. 14, no. 1, 1998, pp. 28-30; Leon B, Taranto, “Ottoman Empire Sephardim: Historical Migrations and Genealogical Resources” and “Consolidated List of References and Recommended Publications,” Sharsheret Hadorot - Journal of Jewish Genealogy, vol. 14, nos. 2-3, Israel Genealogical Society, Fall 1999 and Winter 2000.

53 Roland Taranto, “Les Nomes de Famille Juifs de Smyrne,” ETSI - Revue de Généalogie et d'Histoire Séfarades, vol. 5, no. 16, pp. 3-9, Mar. 2002; Dov Cohen, Izmir - List of 7300 Names of Jewish Brides and Grooms Who Were Married in Izmir Between the Years 1883-1901 & 1918-1933, List No. 1, Summer 1997 - 5757, at pp. 12 and 26. Some personal names for these Taranto’s are prominent in the Leah and Bension branch of our family, such as Sultana, Ester (Esther), Lea (Leah), Caden (Catherine), Avraham (Al), Itzhak (Isaac), and Moshe (Morris).

54 Information on the Italian and Dutch Consulate records was provided by Laurence Abensur-Hazan and Sonja Bilé Vansteenkiste, who recently visited the consulates. The French Consulate in Smyrne (Izmir) issued a Certificate D’Immatriculation for “employé” Isaac Taranto, born 1882 Smyrne, and matriculating on February 22, 1911, to “register matricule de protégés française.” His address is given as ___ York, with the first word obscured, probably New York. (Document provided by Penney Yolles Fraim.)

55 “Taranto” remains one of the “old family names that exist to this day" in Izmir. Stella Kent, "The Blend of Turkish Jews," Mosaic: Genealogy Research on the Jews of Turkey, no. 1, The Roots Committee, Istanbul 1996; Ipeker, “Turkey,” Avotaynu, vol. 12, issue no. 3, Spring 1997, pp. 55-57. One Izmirli was the merchant “Leon Taranto,” born in the late 19th century. He founded a fig and spice export company that his descendants in Izmir still operate today.

56 One Taranto operated in Egypt in 1948 as a Mossad le’Aliya agent, assisting the newborn state of Israel. Michael M. Laskier, The Jews of Egypt: 1920-1970, New York Univ. Press, 1992, pp. 166-67, 194.

57 James Taranto, “He Didn’t Say Uncle – But Salvador Taranto Lived To Be One,” Wall Street Journal, 20 Jan. 2006 www.opinionjournal.com