Grave Matters:

Childhood, Identity, and Converso Funerary Art in Colonial America

By Laura Leibman1 and Suzanna Goldblatt2

When Isaac Lopez was buried in 1762, he joined the remains of many of his extended kin and other members of the Yeshuat Israel [Salvation of Israel] congregation.3 The Hevra kadisha (Burial Society) of Newport washed his body and prepared it for burial. The leader of the burial society then led the men in seven circuits around the body.4 These circuits not only embedded the dead into the memory of the community, but also helped transition the deceased from the world of the living to the world to come. In Judaism, seven is a holy number symbolizing God, completion, and the covenant. One sign of this covenant was separation. Jewish law requires that Jews be buried separately from their gentile neighbors, and in 1677 the Jews of Newport purchased and established a burial ground at the edge of town on the corner of what is now Kay Street and Bellevue Avenue.5 No stones remain from the first 80 years of the cemetery’s history. The cemetery was far from both the town’s Protestant cemeteries, and the houses and businesses of most Jewish residents. After being prepared for internment, Isaac’s body was brought here and buried. A year later a gravestone was erected and ‘unveiled’ (Figure 1).

Gravestone of Isaac Lopez, Touro Cemetery. Photo by Laura Leibman, 2007.

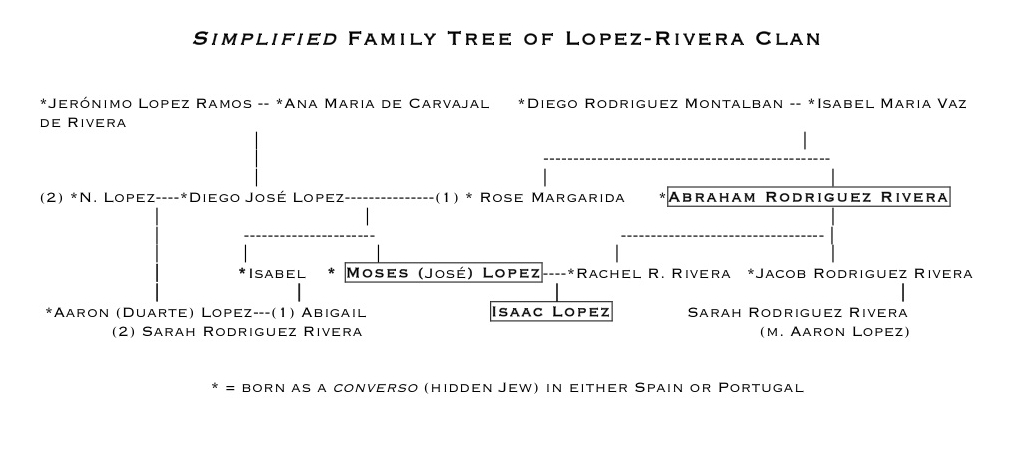

Like the seven circuits made by mourners around the coffins of the dead, the gravestone laid over the tomb had a redemptive quality: it, like other stones in the cemetery, embedded the deceased in the Jewish community of Newport for all eternity, but also insisted upon the interrelatedness of Spanish, Portuguese, Jewish, and Colonial worlds of Isaac’s family. Like many of the Jews buried in the Touro cemetery, Isaac’s father Moses (1706-1767) was a converso or ‘crypto-Jew’; that is, he was a descendent of Jews who had been forced to convert to Christianity and who had for centuries practiced Catholicism in public, and a form of Judaism in private.

Moses Lopez had come to Newport to escape a late wave of the inquisition in Portugal after his New Christian relatives denounced him for ‘Judaizing’. Moses was the older half-brother of Aaron Lopez, one of Newport’s most famous merchants. When Moses came to the Americas, he gave up his Portuguese Christian name (José Lopez Ramos) for a Hebrew one (Moseh) and its English equivalent (Moses). His wife was his first cousin Rebecca Rodriguez Rivera (? -1793), whose father Abraham Rodriguez Rivera (? -1765) had escaped the Spanish inquisition and fled to England and later Newport (Figure 2). Moses was naturalized in New York in 1740/41 and most (or all) of his children were born in Newport. Several of Moses and Rebecca’s children died young, but only the stones of Isaac (1762) and Jacob (1763) remain.6

Family Tree based on Rui Miguel Faisca Rodrigues Pereira, “The Iberian Ancestry of Aaron Lopez and Jacob Rodriguez Rivera of Newport,” Rhode Island Jewish Historical Notes 14(4) 2006 and Malcolm H. Stern, First American Jewish Families: 600 Genealogies, 1654-1977 (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1978).

Isaac’s stone differs from that of his older relatives in that his grave is marked by a vertical stone, rather than the horizontal stones favored by most Sephardic Jews of this era. Both Isaac and his brother Jacob’s graves are graced with an upright (‘Ashkenazi style’) stone with a cherub, and the end of each grave is marked with a footstone with the child’s initials and Hebrew death date. When father Moses Lopez died in 1767, he was buried nearby (Figure 3). His grave is marked with a flat ‘Sephardic style’ ledger stone that contains Hebrew and English inscriptions, but little iconography. Only a small rosette appears in each of the corners. On the top portion of the stone, a quote from Numbers in Hebrew forms a decorative border. His wife Rebecca Lopez died in 1793; although she is not buried in the Newport cemetery,7 her father Abraham is buried near to both her husband and her children. Like his son-in-law’s grave, Abraham’s grave is marked with a horizontal ‘Sephardic style’ stone. Unlike Moses’ stone, it is unadorned, has Spanish rather than English, and contains a lengthy Hebrew elegiac poem. Other members of the extended Lopez-Rivera clan lie nearby. The age differentiation found in the family’s graves can be found throughout this cemetery.

Gravestones of Moses Lopez and Abraham Rodriguez Rivera, Touro Cemetery. Photo by Laura Leibman, 2007.

Thus, in many ways the Lopez family represents a microcosm of the burial trends in the Touro Cemetery. The Touro Cemetery gravestones date from 1761-1860, and of the forty named individuals buried (or memorialized) there, 24 individuals were Sephardim, 11 were Ashkenazim, and five were of unknown heritage.8 There are fifty-two known stones in the cemetery, eleven of which are footstones,9 and three are unknown children’s graves. Like many Jewish cemeteries, children in Touro were buried either near families (as in the case of Isaac Lopez) or in a separate “children’s row” that contained both marked and blank stones.10 Two stones in the cemetery memorialize multiple individuals: one stone memorializes a couple (Reyna Hays Touro and Rabbi Isaac Touro, who was buried in Jamaica), and the other a pair of sisters (Slowey and Catherine Hays). The strong predilection for having one stone per individual, contrasts sharply with the Protestant cemeteries in Newport (such as Trinity Cemetery), the later Jewish Cemetery in Newport, and other colonial American Sephardic cemeteries such as the one in Curaçao.11

Twenty stones are horizontal ‘ledger’ stones or stones with a gabled sarcophagus, sixteen stones (including the three unreadable infants’ stones) are vertical stones, and six are obelisks of the type that were popular in nineteenth-century Protestant cemeteries in New England, but not in other Sephardic cemeteries of this era.12 The percent of horizontal stones is actually quite low, particularly compared to Sephardic cemeteries in the Caribbean: for example the St. Eustatius cemetery has 100% horizontal stones, although it was in use during roughly the same era as Touro and had a similar makeup of Ashkenazi versus Sephardi burials. Likewise the early Sephardic cemeteries in Jamaica, Barbados, and Curaçao from this era have almost 100% horizontal ledger stones; most of the exceptions to this trend are Sephardic pyramidal stones (and later obelisks). In contrast, the colonial Jewish cemetery in New York, like Touro, has a relatively high percent of vertical stones.13 This suggests some regional pressures and variation among early Sephardic cemeteries in the Americas.

The use of horizontal ‘ledger’ stones for adults in the Lopez family and vertical stones for children is typical of the Touro Cemetery, and may reflect the fact that less money was commonly spent on children’s gravestones. In general, there was a strong shift over time in Touro from a mixture of horizontal and vertical stones, to a mixture of vertical stones and obelisks.

While horizontal stones are often considered ‘Sephardic’ and vertical stones ‘Ashkenazi’, all of the children’s stones in the Touro Cemetery were vertical, regardless of the religious affiliation of the parents. Similarly a number of Sephardic adults had vertical stones. Isaac Lopez’s and his brother Jacob’s stones are a good example of how age rather than year or religious background was the most significant factor for determining stone shape: even though they died in close proximity to their father Moses and maternal grandfather Abraham, they were still buried with vertical stones.

Detail of Gravestone of Isaac Lopez, Touro Cemetery. Photo by Laura Leibman, 2007.

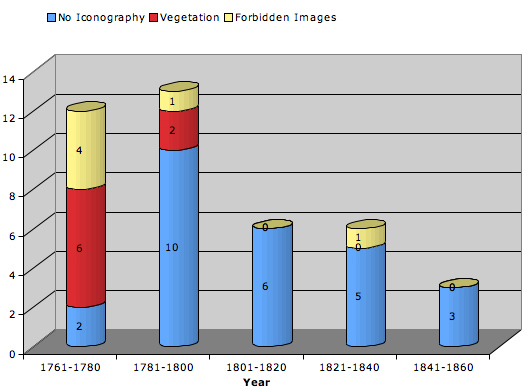

The Lopez-family stones are also representative of the way that iconography on gravestones showed an increased sentimentality towards children. A small, but significant proportion of the stones in the Touro Cemetery contained cherubs on their lunettes, the topmost portion of the stone, in spite of the fact that sculptural representations of divine and semi-divine beings are generally considered to be prohibited by Jewish law (Figure 4). Only in the earliest era (1761-1780) do the majority of stones contain iconography, and even in this era, out of a total of seven stones with iconography, only four (those in yellow)) have forbidden images, while six (those in red) have acceptable vegetation images (flowers, leaves, etc.) (Figure 5).14

Percent of Gravestones with Iconography in the Touro Cemetery. Graph by Laura Leibman.

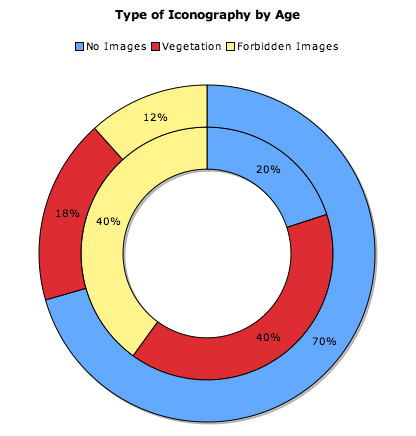

Although children represent only four (10%) of the forty individuals in marked graves, their stones account for one third of the stones with forbidden images (33%) (Figure 6).15 In addition, stones left for adult children by their parents tended to be more effusive in their praise and use of epithets.16 The presence of forbidden iconography on children’s stones in the Touro cemetery needs to be understood in a Sephardic transnational context.

Percent of Gravestones with Iconography by Age. Graph by Laura Leibman.

‘Deviant’ iconographic elements of the Touro Cemetery should be understood as related to Sephardic burial patterns inherited from the Spanish-Portuguese community in Amsterdam, rather than reflecting either a local Christian influence or a reform-minded rebellion against Sephardic orthopraxy. While some of Newport’s Jews came to Newport directly from Portugal and Spain, many came through Amsterdam or its satellite congregations in London, Curaçao, and New York. Moreover, like most of the Jews in colonial America, congregation Yeshuat Israel of Newport itself had strong ties both to the Spanish-Portuguese congregation in Amsterdam and its satellite congregation in Curaçao. The congregation in Newport received funding to build its synagogue from Curaçao and other Amsterdam-affiliated congregations, and Newport’s oldest Torah scroll was a gift from Amsterdam. Newport’s first full-time rabbi, Isaac Touro, came to Newport around 1759 from Amsterdam via the West Indies.17 Perhaps the most significant feature of the Amsterdam’s Beth Haim (in Ouderkerk aan de Amstel) and its offshoots in the Jewish Caribbean is their willingness to use relief sculptures of human forms and of divine beings such as cherubs and other objects usually seen as prohibited by Jewish law.

The Touro Cemetery and its counterparts in Amsterdam and the Caribbean are a good reminder that interpretations of Jewish law need to be read within the context of a community’s own standards. As Rochelle Weinstein has noted, “What was considered normative in Jewish tombstone art has, until recently, been described by Ashkenazim according to Ashkenazi models. Our models of Jewish Orthodoxy, based on records of ghetto life in the Eastern and Western European Diaspora, require modification when we consider the Sephardic experience.”18 Although graven images are forbidden by Jewish law (Exodus 20:4), Jewish communities have interpreted this doctrine differently. At an extreme end, some communities forbid all three-dimensional images whether they be of people, animals, or vegetation; indeed, even in cemeteries that show a higher degree of permissiveness, many of the rabbis’ stones use letters rather than images to decorate the stones.19 A more lenient (and common) position in the eighteenth century was to allow symbols on gravestones that were not commonly worshiped as idols, as the verse that forbids making graven images is immediately followed a prohibition against idolatry (Exodus 20:5). Indeed, images of vegetation, flowers, and Jewish symbols such as Levite pitchers remained common in this era. However, in almost all eighteenth-century Jewish cemeteries, images frequently deified were avoided: angels and cherubim were particularly avoided because, according to eighteenth-century Sephardic commentaries, in ancient times people worshipped the guardian angels of their nations and the astrological forces with which they were associated.20

One of the interesting exceptions to trends in eighteenth-century Jewish gravestone art is the Beth Haim [cemetery] at Ouderkerk aan de Amstel near Amsterdam, and Sephardic cemeteries in the Caribbean that are associated with the Amsterdam congregation: all of these cemeteries contain numerous relief sculptures of human forms and of divine beings. These prohibited images include not only cherubs, but also the hand of God, usually felling the tree of life. Although these images are objectionable by almost any interpretation of the second commandment, they are common not only on gravestones from Amsterdam and the colonies, but also on families’ coats-of-arms, ketubot (marriage contracts), and even a hanukiah [Hanukah lamp]. The ubiquity of “graven images” amongst colonial Sephardim can be felt even in the synagogue: for example, one of the hanging brass candelabra in the Touro Synagogue in Newport has small human heads as part of the decoration (Figure 7: Slide Show).

The presence of these ‘forbidden’ images in Amsterdam and its satellite communities has often been attributed to the strong converso presence in the communities. Conversos who came to Amsterdam or the Americas had often been more fully educated in ‘secular’ studies while in Spain and Portugal and thus admired and collected non-Jewish art. Moreover, Catholicism had a rich iconographic tradition. Although many conversos went to great lengths to return to Judaism after escaping the Iberian Peninsula, scholars have debated greatly to what extent the Catholicism of the conversos impacted the Jewish practice of the colonies and to what group colonial Jews showed the greatest allegiance: Nação (Portuguese-Jewish Nation), Kahal (Jewish Community), or their Dutch or British colony. While Protestants eschewed Catholic ‘idolatry’, eighteenth-century Dutch Protestant tombs of the upper classes in Amsterdam were richly carved with life-size effigies of humans and a range of other images.21 Protestant merchants announced their newfound wealth and social status through their tombstone art. Forbidden images, particularly cherubs, are present in the Touro Cemetery and—not surprisingly—in Newport’s Protestant Cemeteries.

Yet, in the Touro Cemetery, forbidden iconography is statistically linked to age, rather than converso status. While both Moses Lopez and his father-in-law Abraham Rodriguez Rivera were conversos, there was no ‘forbidden’ imagery on their stones, while the stones of young Isaac and Jacob Lopez who were two to three generations removed from Spain and Portugal contain cherubs. Although Marcus argues that colonial American Jews were “concerned far less with ‘salvation’” than their Christian counterparts,22 the presence of cherubs and increased sentimentality regarding children suggests that the death of a child represented a crisis for parents who sought to make meaning from the early loss. Cherubs tend to stress resurrection, unlike either death’s heads or symbols of the hand of God cutting down a tree of life, which emphasize the mortality of man.23

In addition to stressing the life of the child in the world to come, cherubs reflect an older style of Sephardic gravestone art that the community was familiar with in Amsterdam and the Caribbean. The slightly ‘old-fashioned’ nature of the cherub may have itself been a source of comfort. As James Deetz and Edwin Dethlefsen note, “children’s burials [are often]… marked by designs that were somewhat more popular earlier in time. In other words, children are a stylistically conservative element in the population of a cemetery.” Deetz and Dethlefsen argue that “While no clear answer can be given to this problem, it may well be that small children, not having developed a strong, personal impact on the society, would not be thought of in quite the same way as adults, and would have their graves marked with more conservative, less explicitly descriptive stones.”24 We would suggest, however, that children’s deaths have a greater impact on a struggling community, not a lesser one. Thus, the conservative nature of children’s stones may be more a sort of consolation—a reaching back for familiar ways of doing things in a rapidly changing world. Thus even as the children’s stones in Touro Cemetery are ‘innovative’ in that they use the cheaper upright stones, they hark back to the Amsterdam predilection for cherubs found in Europe and the Caribbean.

Isaac’s stone then depicts an iconography of multiplicity: it is both conservative and innovative at once. This multiplicity is at the heart of the experience of eighteenth-century conversos and their descendents. As David Graizbord notes, the “central predicament” of the early modern conversos “both inside and outside the Iberian peninsula” lay in the fact that they inhabited a cultural and religious threshold. In Spanish the word converso shares a root with both conversion [conversión] and to converse [conversar]. To be a converso is to hold a dialogue between warring worlds. Religiously, conversos disrupted both Christian and Jewish notions of identity, which saw the boundary between Jews and Christians as “rigid and impermeable.”25 Similarly the national identity of the converso was fraught: were they British citizens, members of the Naçao (Portuguese Nation), or Jews, or all three? Most Jews in Newport had to renounce their Spanish-Portuguese ties to become naturalized. However when the Rhode Island court suggested that they renounce Judaism as well, most Newport conversos decided to cross the border into Massachusetts in order to become naturalized rather than repeat the denials forced upon them by the inquisition.

Tombstones mark the intersection of these thresholds. When conversos died, their families were obliged to account for their lives. We argue that for Newport conversos, gravestones used a shared iconography to unite the divided worlds of their lived selves. While during their lives the identities of ‘Portuguese’ ‘Jewish’ and ‘colonial’ were often at odds with one another, in their funerary art these identities were sublimated under a Jewish self that bridged national and religious boundaries. As the thwarted future of the Jewish community, deceased children and their tombstones represent the most fraught tensions between the portions of converso identity.

Slide Show of Gravestones from various early Sephardic Cemeteries in the Atlantic World. Photos by Laura Leibman and Kent Coupé, 2007-10

Acknowledgements

This paper would not be possible without funding from a Reed College Ruby Grant and from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Summer Stipend Program. We are very grateful to Rabbi Eskovitz (Touro Synagogue) for granting us access to Touro Cemetery and for supervising our visit to it. Several librarians provided guidance for the research: in Newport we were particularly grateful for the generous help of Reference Librarian Bert Lippincott III, C.G. (Newport Historical Society) and Redwood Librarian Lisa Long. We owe a debt of gratitude to Rabbi and Mrs. Sarah Greer and their extended family for their hospitality in Newport and New Haven.

The data collected for this study was a team effort, and we are grateful to all involved. Several people worked on photographing, making Excel spreadsheets, and creating seriation charts for the following cemeteries: Touro Cemetery, Newport RI (photography, Laura Leibman and Zan Goldblatt; Excel database and charting, Laura Leibman); God’s Little Acre, Newport RI (photography, Laura and Eric Leibman; Excel database and charting, Laura Leibman); Trinity Church Cemetery, Newport RI (photography, Eric and Laura Leibman; Excel database, Eric Leibman, and charting, Laura Leibman); Jewish Section of Braman Cemetery, Newport RI (photography, Laura and Eric Leibman; Excel database and charting, Laura Leibman); Common Burying Ground, Newport RI (photography, Laura Leibman and Zan Goldblatt); Coddington Burial Ground, Newport RI (photography, Laura Leibman); Old Burying Ground, Groton MA (photography, Laura Leibman); Lowell Cemetery, Lowell MA (photography, Laura Leibman); Abel’s Hill Cemetery, Chilmark MA (photography, Laura Leibman); St. Eustatius Jewish Cemetery (Excel database and charting, Laura Leibman); Jamaica’s Hunt’s Bay Jewish Cemetery (Excel database Zan Goldblatt and Rebecca Schoenberg-Jones; charting, Laura Leibman); Mikve Israel Cemetery, Curaçao (Excel database Zan Goldblatt and Rebecca Schoenberg-Jones; charting, Laura Leibman). Data from St. Eustatius is from Hartog’s The Jews and St. Eustatius; data from Curaçao is from Isaac Emmanuel’s Precious Stones of the Jews of Curaçao; data for Jamaica’s Hunt’s Bay Cemetery is from Barnett and Wright’s The Jews of Jamaica: Tombstone Inscriptions 1663-1880. Evidence for Jewish burials in New York comes from Rabbi de Sola Pool’s Portraits Etched in Stone and the 1654 Society website. Joshua Segal’s The Old Jewish Cemetery of Newport: A History of North America's Oldest Extant Jewish Cemetery was essential for our research in Touro Cemetery, and we are grateful to him for providing us with an advance copy of the book. Photographs of the gravestones mentioned in this article, as well as from other early Sephardic cemeteries in Ouderkerk aan de Amstel, Hamburg, London, Jamaica, Curaçao, Barbados, Suriname, and other parts of the colonies can be found in the Jewish Atlantic World Database: http://cdm.reed.edu/cdm4/jewishatlanticworld .

Notes:

1. Laura Leibman is a professor of English and Humanities at Reed College and the author of Messianism, Secrecy, and Mysticism: A New Approach to Early American Jewish Life (Vallentine Mitchell, 2012).

2. Suzanna Goldblatt (the co-author) is a Ph.D. student in Cultural Anthropology at CUNY and a graduate of Reed College.

3. The synagogue was later renamed “Touro” after its first Rabbi Isaac Touro and his philanthropic descendents.

4. Isaac Emmanuel, Precious Stones of the Jews of Curaçao (NY: Bloch, 1957), p. 81.

5. David Meyer Gradwohl, Like Tablets of the Law Thrown Down: the Colonial Jewish Burying Ground. Newport, Rhode Island (Ames, IA: Singler Publishing, 2007), p. 20.

6. Rui Miguel Faisca Rodrigues Pereira, “The Iberian Ancestry of Aaron Lopez and Jacob Rodriguez Rivera of Newport,” Rhode Island Jewish Historical Notes 14(4) 2006: pp. 568, 579. Malcolm H. Stern, First American Jewish Families: 600 Genealogies, 1654-1977 (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1978), p. 175.

7. Many of Newport’s Jews left the town after the Revolutionary War due to the collapse of the shipping industry. Presumably she was buried in a Jewish cemetery elsewhere, though at present the location of her grave is unknown.

8. In this study, we determined whether an individual was Ashkenazi or Sephardic based on a combination of the following types of evidence: (1) identification of individual as Sephardic or Ashkenazi by a reliable earlier historian, (2) Spanish-Portuguese name for men or maiden name for women, (3) genealogical evidence from Stern’s First American Jewish Families and Joseph R. Rosenblum’s A Biographical Dictionary of Early American Jews, and (4) country of origin. Jewish women inherit their religious status from their husbands upon marriage (i.e. an Ashkenazi woman who marries a Sephardic man become Sephardic according to Jewish law); however, for the purposes of this study, we chose to record the religious status of the individual from birth. Since there was a fair amount of intermarriage between Ashkenazi and Sephardic families in Northern colonies during this era, it was more difficult to assess the religious status of women if their maiden name was missing, or genealogical information was weak. All but one of the unknown individuals were women.

9. Footstones mark the foot of the grave and help visitors from stepping directly over the body of the deceased. They tend to be smaller than their accompanying headstone and to have little information or decoration on them.

10. These stones were either never marked or were of a lesser quality and hence have been erased by weather and time.

11. For example, in sections two and three of the later Jewish cemetery in Newport (1846-2004), 53% of the people memorialized either shared a stone or had stones created to match a family member’s stone. In the Touro cemetery, only two stones were shared and only two stones were made to mimic that of a spouse (10% total).

12. Gradwohl, Like Tablets of the Law Thrown Down, pp. 26, 18.

13. David de Sola Pool, Portraits Etched in Stone: Early Jewish Settlers, 1682-1831 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1953), p. 183.

14. Three stone have both cherubs and vegetation. After 1787 only one stone in the Newport cemetery has a semi-forbidden image, and that is Jacob Lopez’s stone (1882) which contains a less problematic death’s head as opposed to the earlier stones which all contain cherubs. This stone is an anomaly by all accounts, in that skulls had become unpopular throughout New England by 1822 and the poor workmanship of the image is in marked contrast to the high quality of the Hebrew lettering. Although odd by Newport standards, there are other examples of late and deliberately ‘primitive’ death’s heads in both New England and in Caribbean cemeteries. One example is the stone of Abraham Cohen (5450/1790) (AJA Photo). In his article on Skeletal ‘Revivals’ in Essex County, MA, Peter Benes notes that there was a short-lived popularity of skull images “at a time (1737-1784) when the image elsewhere was rapidly being animated and/or replaced” (Benes 72). There are also examples in New England of later carvers deliberately invoking either the death’s head and/or earlier slate style, either as a form of religious and cultural nostalgia (Mary Nesbith stone [1929], Lowell Cemetery, Lowell MA) or for reasons of kitsch (John Belushi’s stone [1982], Abel’s Hill Cemetery, MA).

15. Even if one assumes that the three illegible stones in the children’s row were always unmarked (rather than erased), the percent of children with forbidden images on their stones is unusually high (22% as opposed to 12% for adults).

16. An example of this is the Rachel Lopez stone (1789).

17. Morris A. Gutstein, The Story of the Jews of Newport; Two and a Half Centuries of Judaism, 1658-1908 (New York: Bloch publishing Co., 1936), p. 72.

18. Weinstein, Rochelle, “Storied Stones of Altona: Biblical Imagery on Sephardic Tomb stones at the Jewish cemetery of Altona-Koenigstrasse, Hamburg,” (1995) Rochelle Weinstein Collection. Leo Baeck Institute (LBI) Archives. 2.

19. For example see Rabbi Karigal’s gravestone in Barbados (Emmanuel 480-83) or Rabbi Morteira’s or Rabbi Menasaeh ben Israel’s gravestones in Amsterdam (Castro 56-59).

20. Yaakov Culi, Me’Am Loez: the Torah Anthology, vol. IX. Tr. Aryeh Kaplan. (NY: Moznaim Publishing Co., 1990), p. 187.

21. Frits Scholten, Sumptuous Memories: Studies in Seventeenth-century Dutch Tomb Sculpture (Zwolle: Waanders, 2003).

22. Jacob Rader Marcus, The Colonial American Jew, 1492-1776 (Detroit: Wayne State U.P., 1970), p. 1057.

23. James Deetz and Edwin S. Dethlefsen, “Death's Head, Cherub, Urn and Willow.” Natural History Vol. 76(3) 1967, pp. 30-31.

24. Deetz and Dethlefsen, “Death's Head, Cherub, Urn and Willow,” p. 36.

25. David L. Graizbord, Souls in Dispute: Converso Identities in Iberia and the Jewish Diaspora, 1580-1700 (Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P., 2004), p. 2.

Bibliography

Barnett, R.D. & P. Wright. The Jews of Jamaica: Tombstone Inscriptions 1663-1880. Jerusalem: Ben Zvi Institute, 1997.

Baugher, Sherene and Frederick A. Winter, “Early American Gravestones,” Archaeology 36(5), September/October 1983: 46-53.

Benes, Peter, “A Peculiar Sense of Doom: Skeletal `Revivals’ in Northern Essex County,” Markers. 1984 (3): 71-92.

Biedermann, Hans. Dictionary of Symbolism, tr. James Hulbert. NY: Penguin, 1992.

Calvert, Karin. Children in the House: the Material Culture of Early Childhood, 1600-1900. Boston: Northeastern U. P., 1992.

Castro, D. H. de. Keur van Grafstenen op de Portugees-Isräelietische Begraafplaats te Ouderkerk aan de Amstel met Beschrijving en Biografische Aantekeningen. Ouderkerk aan den Amstel, Holland: Stichting tot Instandhouding en Onderhoud van Historische Joodse Begraafplaatsen in Nederland, 1999.

Census of the Colony of Rhode Island, 1774. Arranged by John R. Bartett, Secretary of the State. Providence: Knowles, Anthony, & Co. 1858.

Crane, Elaine Forman. A Dependent People: Newport, Rhode Island in the Revolutionary Era. New York: Fordham U. P., 1992.

Downing, Antoinette Forrester and Vincent J. Scully, Jr. The Architectural Heritage of Newport, Rhode Island, 1640-1915. 2d ed. New York, C. N. Potter, 1967.

Gitlitz, David M. Secrecy and Deceit: the Religion of the Crypto-Jews. Albuquerque: Univ. of New Mexico Press, 1996.

Hanukiah, Gomez Mill House. Marlboro, NY.

Hartog,Johan. The Jews and St. Eustatius. St. Maarten, Netherlands Antilles, 1976.

Heads of Families First Census of the United States: 1790 State of Rhode Island. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1908.

Kusinitz, Bernard, “The Enigma of the Colonial Jewish Cemetery in Newport, Rhode Island: Myths, Realities, and Restoration,” Rhode Island Jewish Historical Notes. 9(3) 1985: 225-238.

Lippincott, Bert. Conversation July 5, 2007. Newport, Rhode Island.

Luti, Vincent F. Mallet & Chisel: Gravestone Carvers of Newport, Rhode Island in the 18th Century. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2002.

Nadler, Steven. Rembrandt’s Jews. Chicago: U. Chicago P., 2003.

A Plan of the Town of Newport in Rhode Island Surveyed by Charles Blaskowitz, engraved and publish'd by Willm. Faden. Map. London: 1777. Map Collections 1500-2004. American Memory. Lib. of Congress. 14 Aug. 2007 <http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3774n.ar101301>.

Price, Edith Ballinger, ““The Court End of Town,” NHS Bulletin No. 108, April 1962: 4-22.

Ritchie, George W. et. al. “Map and Index, Common Burying Ground. Newport, RI” (1903). Newport Historical Society.

Rosenbloom, Joseph R. A Biographical Dictionary of Early American Jews: Colonial Times through 1800. Lexington, KY: U. of Kentucky P., 1960.

Schulz, Constance B., “Children and Childhood in the Eighteenth Century,” American Childhood: a Research Guide and Historical Handbook, ed. Joseph M. Hawes and N. Ray Hiner. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985: 57-110.

Segal, Joshua. The Old Jewish Cemetery of Newport: A History of North America's Oldest Extant Jewish Cemetery. Nashua, NH: Jewish Cemetery Publications, 2007.

Shemot/Exodus, ed. Rabbi Eliezer Toledano. Lakewood, NJ: Orot, Inc., 2006.

Shilstone, E.M. Monumental Inscriptions in the Jewish Synagogue at Bridgetown, Barbados: with Historical Notes from 1630. Roberts Stationery, Barbados: Macmillan, 1988.

Simmonds, Paula. 1654 Society Cemetery Website 1 February 2006 <http://www.1654society.org> 26 August 2007.

Stiles, Ezra “Miscellaneous Papers,” Ezra Stiles Papers. Beinecke Library, Yale University.

Tashjian, Ann and Dickran Tashjian, “The Afro-American Section of Newport, Rhode Island’s Common Burying Ground,” Cemeteries and Gravemarkers: Voices in American Culture, ed. Richard E. Meyer. Logan, UT: Utah Sate U.P., 1992: 163-96.

Tashjian, Dickran and Ann Tashjian. Memorials for Children of Change: the Art of Early New England Stonecarving. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan U. P., 1974.

“Tax Assessment for the Town of Newport, 1772,” BM MS Box. Newport Historical Society.

Weinstein, Rochelle. “Sepulchral Monuments of the Jews of Amsterdam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” Ph.D. New York University, 1979.

Weinstein, Rochelle, “Storied Stones of Altona: Biblical Imagery on Sephardic Tomb stones at the Jewish cemetery of Altona-Koenigstrasse, Hamburg,” 1995. Rochelle Weinstein Collection. Leo Baeck Institute (LBI) Archives.

Wells, Charles Chauncey & Suzanne Austin Wells. Preachers, Patriots & Plain Folks: Boston's Burying Ground Guide to King's Chapel, Granary, Central. Oak Park, IL : Chauncey Park Press, 2004.

Wilson, Thomas. A Complete Christian Dictionary Wherein the Significations and Several Acceptations of all the Words Mentioned in the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testament are Fully Opened, Expressed, Explained. London: E. Cotes, 1661.

Youngken, Richard C. African Americans in Newport. Newport, RI: Newport Historical Society, 1998.