Film Review: Besa: The Promise

Directed by Rachel Goslins

2012. Produced by Jason Williams, William Morgan, Rachel Goslins and Christine S. Romero. A Documentary Film by JWM Productions. In English, Albanian, and Hebrew.

Reviewed by Judith Roumani

This award-winning documentary tells the story of a number of courageous Albanians, most of them Muslims but also some Christians who, while their country was occupied by the Nazis, hosted and hid Jews who were fleeing from Central and Southern Europe. Though many of these Jews were Ashkenazim, some were Sephardim from Bulgaria, Greece or Yugoslavia. The Albanians lived up to their tradition of hospitality to strangers and opened their homes with great generosity. The title of Besa: The Promise refers to another trait of traditional Albanian culture: a person’s word, once given, is not to be broken or forgotten. The Jews who made the fortunate decision to flee to Albania found themselves protected, disguised to fool the Germans, treated as members of the family, hosted, clothed and fed until the war was over and it was safe to leave.

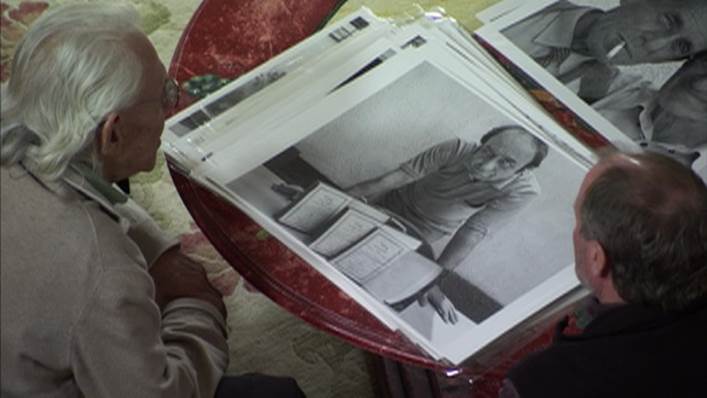

The film takes up a specific story, discovered by an American photographer, Norman H. Gershman, who recently travelled to Albania to take still photographs of Albanians who had saved Jews for a book and exhibit he was creating. The film shows him visiting some of these elderly people, chatting with them to make them feel comfortable, and then catching a moment of joy on their faces. One of his subjects is Rexhep Hoxha, born in 1950 and the son of a now deceased Albanian saver of Jews. Rexhep has a problem, perhaps a uniquely Albanian type of problem: he must fulfill a besa, a promise that his father had once made and that after his father’s death now devolves onto his shoulders. The promise is to return three Hebrew-language books to the Jewish family that had entrusted them to him. When it had become safe to leave, the family, whose name was Aladjem, Sephardim who had fled Bulgaria, left by sea for Mandate Palestine and in view of the dangers of the voyage decided to leave their precious books in the temporary safekeeping of their Albanian hosts.

The Communist decades intervened. Albania was hermetically closed, and no one could visit. There were not even postal services. Moreover, religion was outlawed and it became extremely dangerous to own religious books—even if one could not read them. Hoxha père built a wooden box to fit the books in, and hid it at the very back of his bookshelves. As religious Muslims, they could only pray in their hearts.

Eventually even this regime passed, but the father had died, and Rexhep now was anxious to fulfill his father’s promise so that he would not have to pass it down to his own son. He could find no information or leads apart from the family’s names until Norman Gershman offered to help. Now, in the internet age, it was possible to find documents and trace the family’s origin in Bulgaria. There also, the Communist years have almost obliterated traces of religion and especially of Judaism. They visit Bulgaria and see the synagogue where the Aladjem couple had been married before the war, now a roofless, weedy shell, but still conveying the beauty of a magnificent synagogue, obviously once the pride of a proud community. Now the film producer and photographer succeed in locating the Aladjem family, who are living in Tel Aviv.

The plan is for Rexhep and his adult son to travel to Israel and present the books to the Israeli family. We see the Albanians visiting Jerusalem, its Muslim sites and also the Kotel, where they leave a prayer. There is considerable suspense after their encounter with the adult son of the former little boy who had been hidden in Rexhep’s house (the original parents being by now deceased). He says his father never spoke of that period in his life and would not be amenable to meeting them. Nevertheless they arrive at the door of the apartment, and there is an extremely emotional reunion. Mr. Aladjem (whose family name now is Etrog) describes how the Hoxha parents had sheltered him very warmly and treated him like their own son—their demonstrative affection contrasting with his own very reserved parents. The books (which are mahzorim or Sephardic High Holiday prayer books, published in Vienna) are returned, and the besa has been fulfilled.

The film, when I saw it, was screened at Georgetown University, under the auspices of the Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding, and the Program for Jewish Civilization. In the audience were several young Albanians, who were very interested in this sensitive and emotional rendering of their culture. Several spoke afterwards and attributed the courage of their elders, many of whom have been recognized as righteous gentiles by Yad Vashem, to the specific Albanian cultural traits of hospitality and of keeping one’s promise. The fact that a majority of these saviors were Muslims, though interesting to us, seemed less relevant to the young Albanians present. One trusts that Albanians will not lose their parents’ heartwarming and admirable cultural traits in a rush to modernity.

This film is highly recommended, with sensitive direction and photography, beautiful and effective music by Philip Glass, and is obviously the fruit of the several years of meticulous research that went into its making. Its optimistic message will restore one’s faith in the power of good in human nature to overcome religious prejudices.

Judith Roumani is the Editor of Sephardic Horizons