An Ode to Salonika: The Ladino Verses of Bouena Sarfatty

By RenÉe Levine Melammed

Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013, 308 pp. Print.

Reviewed by Judith R. Cohen

Bouena Sarfatty Garfinkle was born in Salonika, today's Thessaloniki, in 1916 or 1918 (see Melammed 261, n.1) and died in Montreal in 1997. Having interviewed her several times in the early 1980s as part of the fieldwork research for my dissertation on music in Canadian Sephardic communities, I was especially interested to read Renée Levine Melammed's volume. While working with Bouena as a nascent ethnomusicologist, I centred our sessions on her song repertoire and the contexts she explained for them. I recorded, of course, her hundreds of proverbs and what she called 'komplas', the Salonikan Sephardic term for the poetic form coplas. At the time, however, I was not able to fulfil Bouena's request that I focus my work on her material, both musical and non-musical. It is thus fitting that Melammed's fine volume has appeared, bringing to life precisely the elements which I could mention only briefly in my dissertation.

The tragic fate of Salonika's Jewish community in the Holocaust is not an easy story to tell. Melammed, a historian especially appreciated for her work on the history of the Crypto-Jewish women of Spain, has risen to the challenge of weaving the story of Bouena's life into its historical context. She ably discusses the history and culture of the Salonika Jewish community, acknowledging the input of elderly Salonican Sephardim and other native Ladino speakers and experts she consulted. Melammed provides a concise but well-informed and sensitive account of the horrific events of the Holocaust in Salonika, and recounts Bouena's role as a then young partisan. The coplas themselves are set out clearly, in Judeo-Spanish with facing English translations and accompanied by well-informed, valuable footnotes.

When, some years ago, I began to revisit my 1980s recordings of Bouena, I was struck by the many songs which reflected daily life, rather than the typical 'top ten' lyric songs so often performed today in concerts and on recordings; indeed, Bouena herself told me she wanted to avoid "the songs everybody knows." The coplas complement and detail the daily life reflected in Bouena's song repertoire, from women's fashions to wedding customs to unflinching accounts of events during the war. Several coplas describing community life are satirical, and Bouena's own opinions are always clear:

In the old days, the women had long hair that was beautiful to see,

Today they have it cut like a boy and it looks awful… (#347, 155)

We hear about the Jewish National Fund, local charity organizations, who was rich and who was poor, who was generous and who was stingy… where one played poker and where one went for good books…. engagements, Jewish festivals, schools and the first phonographs. The stark descriptions of war circumstances are all the more chilling because of their contrast to these colourful, sharp depictions of day-to-day life.

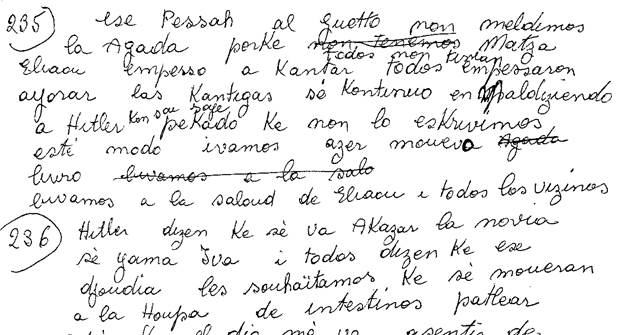

The Germans took dogs and radios from us… (#55, 219)…In war no one wins. Only mothers cry… (#4, 223) We in the ghetto are terrified to speak… (#52, 227) Hitler wants us to travel in order to kill us… (#64, 237).

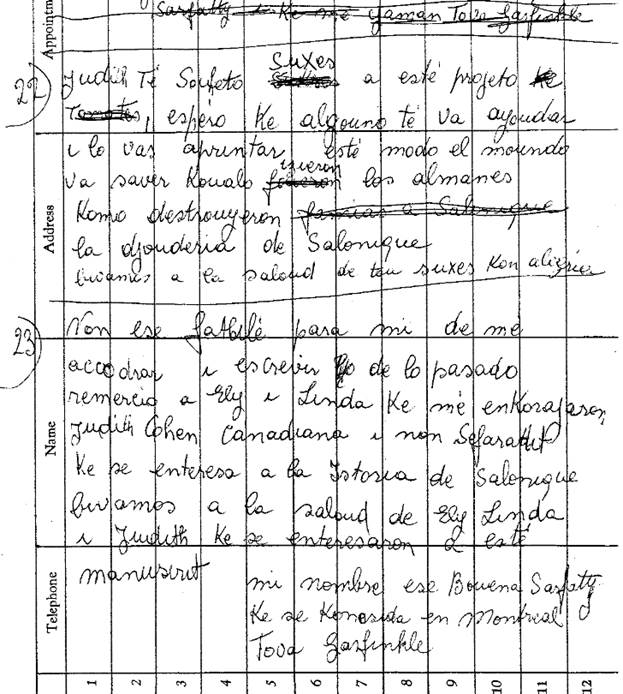

Bouena presented her coplas to me as 'toasts', rather than as poetry, and indeed each ends with "let us drink to the health of…." Melammed summarizes the history, form and themes of the Sephardic coplas genre, and points out that they were typically composed by men (11-14). She explains her decision to group them according to themes she herself worked out (17-18), rather than in the seemingly random order of Bouena's handwritten manuscript; however, she does take care to provide the original number of each one, so those interested can reconstruct the order they were written in. The coplas specifically about the war are grouped separately, following the others. Many of these are less pithily written than those describing social life, with longer, more complex sentences, sometimes almost resembling brief war news updates, but each still ends with the line "let us drink to the health of…."

Comparing the coplas in this volume with my photocopies of the collection Bouena loaned me over a decade earlier, I found that Bouena appears to have rewritten them more neatly, and on blank paper, rather than the ones in my collection, for which she used stationery from her husband's business (she used this stationery for the song lyrics and proverbs she recorded for me as well). For the most part the coplas are the same in both collections, though often in a different order e.g. #107 in my collection is #289, page 94 in Melammed's, and in some cases slightly altered. Melammed speculates about images and memories which might have been going through Bouena's mind as she wrote the coplas out, and whether these may have influenced the order of her manuscript (268, n. 100). As the order of the coplas is different in my copies of Bouena's earlier manuscript, it might be enlightening to compare the two collections. Bouena gave no titles or sub-titles in the manuscripts she loaned me, aside from the single word "Komplas" at the beginning of the first page. About twenty-five coplas in my collection appear to have been omitted in Melammed's; among these are one dedicated to me (and my name is omitted in another, which in my collection names me together with Bouena's son Ely and daughter-in-law Linda).

There are few errors in the book. Melammed writes that the emblematic woman wedding singer of nineteenth-century Salonika "Bona la Tanyedera" played a "Basque drum" (274, n. 87). The instrument in question is not a Basque drum, but rather a tambourine: "Basque drum" is a literal translation of the French tambour de Basque (an employment that confirms Bouena's French fluency, and reveals her tendency to use many French terms). The term typically used in Judeo-Spanish in Salonika for this tambourine was panderico.

The year of Bouena's death is given as 1997 on page ix, but in the dedication appears as 1995. A useful glossary is provided, but it would have been helpful to have a list of the coplas' incipits in alphabetical order, or at least the original numbers provided by Bouena in order, with the page they appear on in Melammed's book. While the bibliography and the living resource people consulted are excellent, the note about the songs (270, n. 21) should include both Rivka Havassy's and my own work for discussions of Bouena's songs, though the bibliography does include the relevant titles.

These are minor cavils: this fine volume provides indispensable insights into the lives of the Jews of Salonika in the years before and during the Holocaust, both in the words of Bouena Sarfatty herself and in the author's presentation.

References

Cohen, Judith R. "Selanikli Humour in Montreal: the Repertoire of Bouena Sarfatty Garfinkle." Judeo-Espaniol: Satirical Texts in Judeo-Spanish by and about the Jews in Thessaloniki. Eds. Rena Molho, H. Pomeroy and E. Romero. Thessaloniki: Ets Ahaim Foundation, 2011.220-42. Print.

Havassy, Rivka. "'Si mosós no vamos a recoger…', the Songbooks of Emily Sene and Bouena Sarfatty-Garfinkle." Los Sefardíes ante los retos del mundo contemporáneo: identidad y mentalidades. In Paloma Díaz-Más and María Sánchez-Pérez. Eds. Madrid: CSIS, 2010. 247-256. Print.

Illustrations: Cohen R., Judith. Bouena Sarfatty Garfinkle n Her Home. 1981. Photograph. Montreal.

Bounea Sarfatty Garfinkle. "Coplas about Hitler." "Coplas mentioning Judith Cohen,Ely Garfinkle and Linda Garfinkle." Collected by Judith R Cohen.

Dr. Judith R. Cohen is an ethnomusicologist, music instructor and performer at York University, Toronto, Canada.