Code-Switching and Immigrant Identity in Rosa Nissán’s Hisho que te nazca

by

Rey Romero

1

Code-switching is the linguistic term for the alternation of two or more

languages (codes) between and within sentences in the discourse of one

speaker (Poplack, 581). Although this phenomenon is typical of the speech

(oral production) of bilinguals, several authors have implemented

code-switching as a literary or poetic device to portray the bilingual and

bicultural setting or character (Keller, 178). This paper focuses on the use

of code-switching, namely Spanish and Judeo-Spanish, in the literary work of

Mexican Sephardic author Rosa Nissán.

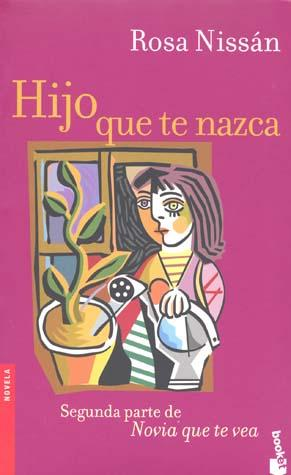

Nissán debuted her literary career in 1992 with

Novia que te vea, a novel that

relates the childhood and womanhood of Oshinica, a first-generation Mexican

of Turkish Sephardic parents.

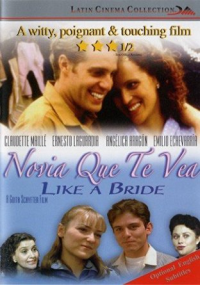

This novel and the subsequent eponymous film introduced Sephardic language

and culture to the Mexican public at large, emphasizing commonalities

between the immigrant and national groups. Because of the success of

Novia que te vea, both novel and film have been reviewed and

critiqued in several articles, most thoroughly by Halevi-Wise (1998) and

Alfaro-Velcamp (2006). In this paper, I will focus solely on Nissán’s second

novel, Hisho que te nazca,

published in 1996, because it has not been studied previously from either a

literary or linguistic angle, and I believe Judeo-Spanish is utilized more

as a literary device and less as a linguistic curiosity. In this paper, I

will describe the characteristics of the code-switching present in

Hisho que te nazca and will discuss several motivations for its

implementation throughout the novel.

One of the interesting issues regarding the novel’s code-switching is that

Spanish and Judeo-Spanish are considered to be two dialects rather than two

languages. In linguistics, the

critical point to decide between a language and a variety (lect) of a

language is mutual intelligibility. If two linguistic groups are mutually

intelligible, then they speak dialects of the same language. Both of

Nissán’s novels are written in what we may call an academic version of Latin

American Spanish, but the dialogues are interspersed with Mexico City

Spanish (also known as chilango)

and Judeo-Spanish. In spite of the common origin of all these varieties of

Spanish, the geographical distance and lack of familiarity with the Spanish

of the other community could pose an intelligibility challenge for the

reader. The author has attempted to minimize this obstacle by providing a

Judeo-Spanish/Spanish glossary at the end of both

Novia que te vea and

Hisho que te nazca. The reader

finds unfamiliar Judeo-Spanish words in italics, thereby indicating its

‘otherness’ and their explanation in the glossary. It is interesting that

the reader is assumed to be familiar with

chilango Spanish, as the author

did not provide italics or glossary for this dialect.

However, from a linguistic point of view, it is clear

why Nissán assumed that the reader might need additional help

understanding Judeo-Spanish, as it diverges from Latin American Spanish at

the phonological (pronunciation), morphological (word formation), and

lexical (vocabulary) level. For instance, Judeo-Spanish maintained the Old

Spanish palatal system (with additional changes), as illustrated by the

pronunciation of <j> in mujer

‘woman’ and ojo ‘eye’ like the

second <g> in ‘garage’ (a voiced palatal fricative in phonological terms).

In Peninsular and Latin American varieties, this Old Spanish fricative

became a velar [x] or glottal [h]. This particular phonological divergence

is readily illustrated in the novel’s title, as the author has attempted to

transcribe the voiced palatal fricative with <sh> in the word

Hisho (Spanish

hijo). This is also exemplified

throughout the novel with the name of the main character,

Oshinica, the Sephardic adaptation

of the French Eugénie plus the

Judeo-Spanish diminutive -ika. I

believe that the fact that this distinct Judeo-Spanish pronunciation is part

of the main character’s name serves as a literary device to instantly remind

the reader of the protagonist’s Hispanic and Jewish background, something

both familiar and unfamiliar to the predominantly Catholic Spanish-speaking

public, and also establish an indelible link between Oshinica and her

Sephardic identity, a key theme throughout the novel. Other examples of

palatal vs. velar divergence present in the novel include

bashar (Spanish

bajar ‘to lower’),

deshar (Spanish

dejar ‘to leave out’), and

viesha (Spanish vieja ‘old

woman’). Due to orthographical limitations in Spanish, Nissán utilized the

same digraph <sh> to transcribe both voiced and voiceless palatal

fricatives, which are distinct phonemes in Judeo-Spanish. Other examples of

phonological divergence explained in the novel’s glossary include the

preservation of initial /f/: fuir

‘to escape, flee’ (Spanish huir)

and metastasis of the consonantal group /dr/:

tadre ‘evening’ (Spanish

tarde).

These phonological differences conveyed through orthography could

easily be solved by the reader by inferring from their context, yet the

author chooses to address them in the glossary. This illustrates how

important the “voice” of Judeo-Spanish is for the novel, since the reader

must hear it at its essence even when the lexical items are basically the

same and pronunciation differences are minimal.

On the other hand, a key point for the Spanish reader is confronting the

divergent Judeo-Spanish lexicon, especially those items inherited from Old

Spanish or adapted from Hebrew, Turkish, French, and other Mediterranean

languages. Judeo-Spanish

vocabulary contains Old Spanish lexical items that have either fallen into

disuse or that are considered archaic or rural in certain areas of Latin

America and Spain (Romero, 52). Examples of these items in the novel include

topar (Spanish encontrar

‘to find’), merkar (Spanish

comprar ‘to buy), and

consesha (Spanish

cuento de

moraleja ‘fable with moral

lesson’). In addition to this layer, like most languages of Jewish groups,

Judeo-Spanish vocabulary is also characterized by Hebrew and Aramaic items,

especially to convey religious and cultural concepts (Wexler, 99). Oshinica

and her family use the following, among others:

benadam ‘human being,’

mazal ‘luck,’

tevilá ‘ritual bath,’ and

Shabat ‘Sabbath.’ The final layer

is composed of borrowings from French and Turkish. This is not surprising

since Oshinica’s family hails from Turkey, and in the early twentieth

century there the language of Western education and upper mobility was

French. Oshinica’s family

immigrated to Mexico soon after World War I, a time when Turkey experienced

a surge in nationalism, including Turkish-only language policies (Sachar,

104). Examples of Turkisms incorporated into the novel’s Judeo-Spanish

include deli ‘crazy’, englenear

‘to have fun’, mushteris

‘customers’, and sarjosh ‘drunk’.

These divergent phonological and lexical features indicate a switch in the

code in the speech of characters. These characteristics let the reader know

that the language is now Judeo-Spanish, and I will discuss the purpose of

this switch in a subsequent section.

However, in spite of being an artificial version of code-switching, because

it has been created by the author and not documented through

naturally-occurring linguistic data, the Judeo-Spanish and Spanish

alternation in the novel mimics the patterns found in real-life bilingual

speakers. Moreover, these

patterns have been studied with empirical linguistic data.

According to Poplack (609), fluent bilinguals tend to make more

switches inside the sentences, known as intra-sentential switches. For

example, “tiene que coser parte de la camisita para el bebé, echar

dulzurías y bendiciones entre la

ropita” (She has to sew part of the baby’s shirt, throw in

sweets and blessings amid the

clothes). This sentence is mostly in Spanish, but the word for sweets,

dulzurías, has been rendered in Judeo-Spanish.

However, most of the novel’s switches actually occur between

sentences, in inter-sentential code-switching. Poplack’s research

demonstrated that less-fluent bilinguals preferred this kind of switching,

probably because their lack of fluency prevented them from incorporating

elements from one language into the grammar of another (609).

To

illustrate, observe this inter-sentential code-switching, “Mira qué

yuselicas cosas te trusho de Houston, es muy buen padre.

Hazlo por tus hishicos. Ya quisieran muchas tener un marido como el

tuyo” (Look what beautiful things he brought you from Houston, he’s a good

father.

Do it for your children. Many

would like to have a husband like yours). The first two phrases contain

phonological and lexical elements characteristic of Judeo-Spanish, but the

last sentence has changed to Spanish, as evidenced by the pronunciation of

muchas (Judeo-Spanish munchas).

But, overall, the most common pattern in Oshinica’s language is the

usage of single Judeo-Spanish items in the Spanish discourse.

In linguistics, these temporary, single-word switches are denominated

‘nonce borrowings’ and in Oshinica’s speech they appear to depict cultural

concepts or practices such as ashugar

(bridal dress), fashadura

(ceremony similar to a baby shower),

dulzuría (typical sweets).

The older Sephardic women characters, especially her mother and aunts, use

longer Judeo-Spanish sentences, and rarely any

chilango Spanish lexicon.

Curiously, Oshinica’s Judeo-Spanish usage mimics her use of Hebrew,

as the hagiolanguage only appears momentarily to depict a Jewish concept

that would be difficult to explain in Spanish:

Shabat,

matzá, Rosh Ashaná,

Pesaj,

bar mitzvoth, birith,

among others.

Nissán has managed to establish the divergent dialectal characteristics of

Judeo-Spanish and also mimic realistic code-switching patterns throughout

her novel. But the reason behind

this language alternation may be a bit more nuanced. In the beginning of

Novia que te vea, her first novel,

Oshinica explains that she is using Ladino (her preferred nomenclature for

Judeo-Spanish) “para que se diviertan,” for the amusement of the reader.

But, beyond entertainment, I believe that this code-switching is necessary

in order to give an accurate depiction of the transition from the

Judeo-Spanish immigrant family to the first generation Mexican child. This

child would probably grow up bidialectal, with the ability to navigate

between the two cultures and their corresponding “Spanishes,” albeit mixing

them. The following illustrates this dialect mixing within Oshinica’s home:

-Aide Bulizú, ¿de qué abrithes [sic]

esta ventana?, mos estamos entesando.

“Y cerren, cuando lleguí me estaba atabafando.

“Cuando quieras oír más janum, ven una tadre a mi caré con las de la calzada

de La Piedad, ahí sí te vas a englenear.

-Hey, Bulizú, why did you open

this window? We are freezing.

“So close it, when I arrived I

was suffocating.

“When you want to hear more, ma’am, one of these evenings you should come to

my game night, with the women from La Piedad Avenue, now that’s a lot of

fun.

-Damn, I think my husband is probably home by now and he gets furious if I’m

not there.

This example reflects several linguistic patterns that appear throughout the

novel. First, most Judeo-Spanish dialogues occur when the older characters

are speaking or when Oshinica is quoting them. Judeo-Spanish rarely occurs

within Oshinica’s dialogues or thoughts. Numerically speaking, roughly one

third of all Judeo-Spanish code-switches occur within Oshinica, and most are

nonce borrowings. When comparing

both of Nissán’s novels, we see that Oshinica’s Judeo-Spanish in

Hisho que te nazca contrasts with her younger self in

Novia que te vea, as the character

has become more Mexican and less immigrant.

This is reflected in her independence and feminism, as she breaks

cultural taboos with her divorce and in pursuing a career in the arts and

letters. Ultimately, the author

has allowed for this transformation to be reflected in the language as

Judeo-Spanish gives way to language mixing and, most strikingly, Oshinica’s

predilection for chilango Spanish.

She uses the Mexico City dialect even to address the older Sephardic

women, as in the previous dialogue.

She uses phrases such as híjoles (damn) and padre

(cool), her adjectives and adverbs overuse the diminutive -ito: nadita (nothing) and

she emphasizes them with re-:

rebonito (very beautiful).

In short, the purpose of including Judeo-Spanish and Spanish

code-switching in the novel goes beyond providing a mere curiosity, and it

adds a linguistic dimension to the protagonist’s cultural metamorphosis into

a first-generation Mexican and her battle between the old country’s mores

and the call of feminism.

Oshinica’s attitude towards Judeo-Spanish also fits a realistic linguistic

situation of first generation families. Whereas the immigrant parents tend

to maintain their heritage language and may or may not become bilingual in

the new language, their children and grandchildren may become semi-speakers

of the heritage language or eventually lose it, but become fluent in the new

language. This first generation may exhibit ambivalent attitudes towards

their own performance of the heritage language, often perceiving it as

imperfect. Oshinica declares

that the older women who play cards with her mother “hablan un ladino

precioso” (they speak beautiful Ladino). Perhaps this comment of admiration

reveals that she is aware that her own Judeo-Spanish is not as authentic or

as fluent as the older generation’s.

In fact, Oshinica’s Judeo-Spanish every now and then includes failed

attempts at Judeo-Spanish forms, as she overcompensates by changing the

pronunciation of Mexican Spanish words:

trabasho (work; Judeo-Spanish

lavoro or

echo), movio (boyfriend,

groom; Judeo-Spanish novio). These

‘fake’ Judeo-Spanish lexical items reveal her linguistic insecurity, and

ultimately, her linguistic patterns in avoiding Judeo-Spanish and embracing

the Mexican dialect.

Although Rosa Nissán has taken a decisive linguistic risk by including

different levels of code-switching with a divergent Spanish dialect, the

effect is an authentic story of growth of first-generation Mexican Oshinica.

By including Judeo-Spanish, the author asserts the protagonist’s

Sephardic identity and also emphasizes her struggle between the two

cultures. This is achieved thanks to the linguistic characteristics of

Judeo-Spanish, a variety distinct from the reader’s Spanish, but familiar

enough to be comprehended and integrated in the text. At the same time, by

including Judeo-Spanish in a Mexican novel, Nissán introduces to a greater

public this particular dialect, thereby providing a literary foothold for an

otherwise underrepresented and endangered language.

Works cited

Nissán, Rosa. Novia que te vea. Mexico City: Planeta, 1992.

Nissán, Rosa. Hisho

que te nazca. Mexico City: Plaza & Janés, 1996.

Sachar, Howard. Farewell España: The

World of the Sephardim Remembered. New York:

Vintage, 1994.

1 Rey Romero (PhD Spanish Linguistics) is Assistant Professor of Spanish Linguistics at the University of Houston-Downtown, where he teaches courses in linguistics and translation. He is the author of Spanish in the Bosphorus: A sociolinguistic study on the Judeo-Spanish spoken in Istanbul (2012) and over a dozen peer-reviewed articles on Judeo-Spanish linguistics. The author would like to thank J. Mushabac and J. Roumani for all their comments and guidance.