Tirant lo Blanch (Valencia, 1490): A 15th century literary rehearsal for a historical confrontation with the non-Christian world

By David A. Wacks *

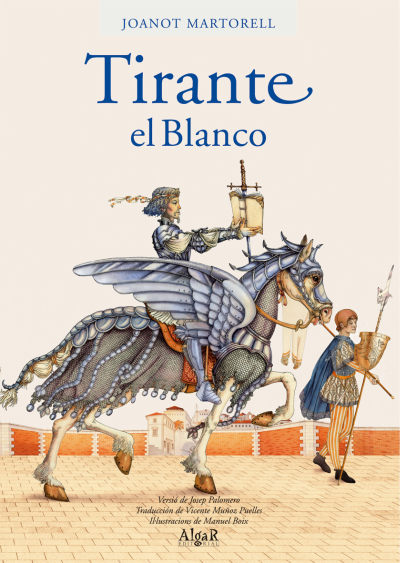

Tirant lo Blanch, begun by Valencian knight Joanot de Martorell in the mid-fifteenth century and completed and published by Joan de Galba in Valencia in 1490, is the story of the knight Tirant, whose adventures span from England to North Africa to Constantinople, where he is eventually crowned Emperor. The novel, an Iberian adaptation of the Arthurian tradition, opens the Arthurian world to the Mediterranean political canvas of Martorell's times. In it, Martorell and Galba give voice to Valencian dreams of renewed Christian expansion in the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa and fears of Ottoman incursion into the Western Mediterranean. The book is a fusion of Arthurian-inspired knightly ideals, nostalgia for the Crusading era, and the geopolitics of the late fifteenth century. Not least of all, as will be seen here, it reflects the very real concerns related to the presence in Valencia of both converted and unconverted Jews and Muslims at the time of its publication, 1490.

Book one of Tirant is a rescension of the Arthurian sequel Guy of Warwick, onto which the adventures of Tirant himself are skillfully welded. The melding of Arthurian and Mediterranean storyworlds is meant to legitimate Valencian knights within the chivalric culture of Western Christendom, while attending to the geopolitical concerns of Aragon, which lay in the Mediterranean world. This projection of current-day affairs onto the legendary British past is a way for Iberian writers to participate in the narrative culture of Western Christendom while tailoring the history-making function of romance to their own historical particularity.

In the novel, Martorell and Galba project contemporary anxieties over the loss of Aragonese territories to Ottoman Expansion in the Eastern Mediterranean, and imagine a fictional Christian "Reconquest" of the former Byzantine capital at a time when Latin Christendom feared Ottoman incursion into the West.

The Romance has always served a para-historiographical function, filling in the gaps and explaining the inconsistencies in the historical record. In Marina Brownlee’s words, romance is “a response to an ever-changing historico-political configuration” (Brownlee 109). As such, it is no surprise that a French romance written in the late twelfth century should differ significantly from one written in Valencia in the late fifteenth. It is also clear that medievals did not have the same expectation of historical objectivity or verisimilitude that we expect today. Barbara Fuchs writes that the romance is not intended to reflect the historical record as does historiographical writing. It has, she writes, “a different purchase on the truth” (Fuchs 103).

At the same time, for a twelfth-century audience, a chronicle and a Romance were not altogether different animals, but rather were situated on a spectrum that ranged from fantasy to court history. The current term “historical fiction” might have applied equally well to the romance as to the chronicle. By the end of the fifteenth century, there are chronicles containing brazenly fictional episodes, such as the fifteenth-century Crónica sarracina, and romances with perfectly historical content, such as Tirant. In short, historical truth claims were not limited to the chronicle but were perfectly acceptable in a narrative fiction.

One of the roles of medieval Iberian fiction is political and spiritual wish fulfillment. It is a record not so much of what has happened but what you wish would happen, if only. Several Medieval Iberian romances fantasize about a Christian East, whether neo-Byzantine, Crusder state, or a mix of the two. This fantasy is sometimes conflated with the domestic fantasy of a Christian al-Andalus or Maghreb. Tirant achieves all of these, knitting together preoccupations with political Islam past and current, domestic and global.

Martorell begins by portraying an Arthurian Britain under siege by the Saracen king of the Canary Islands. Here Martorell fuses the literary imaginary of Western Latin chivalry with that of Martorell’s own time and place. Knights in Martorell’s time patterned their behavior after representations of chivalry in romances (Fallows 263–264). The practice of chivalry had passed from battlefield to tournament, and the aesthetics of chivalry were therefore shaped more by ritual tradition and ideology and less by military exigency. It was, in his day, an institution whose value was more symbolic than strategic.

Aragonese expansion in the Eastern Mediterranean

The fictional world of Tirant is Aragonese as opposed to Castilian. The Crown of Aragon had always looked to the Mediterranean, and was home to important port cities such as Barcelona, Palma de Mallorca, and Valencia. Barcelona, in its maritime heyday, was known as the “Queen of the Sea,” and Mallorca had long been an important trade center and military base. In fact, the Crown of Aragon during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries had come to control a significant maritime empire in the Eastern Mediterranean, an empire that, like the Venetian and the Genoese projects, was fueled far more by commercial interests than by crusading zeal. The crown and nobility themselves engaged directly in trade in ways that were practically unthinkable in the Castilian context (Hillgarth 51; Lowe 3).

By the time Tirant appeared in the late fifteenth century, Valencia had superseded Barcelona as the most important Iberian Mediterranean port. Here the products of all Spain were brought to the Mediterranean market, and goods from around the world entered Spain. This economic bonanza, as it often does, inspired an impressive artistic life, and ushered in what literary historians refer to as the “Segle d’or” or Golden Age of Valencian literature, which preceded the Castilian “Siglo de Oro” by a century.

However, despite the boom economy and political importance of Valencia in the fifteenth century, the Crown of Aragon was no longer the great maritime power it had been in the preceding centuries. While the medieval Catalan chroniclers such as King Jaume I, Ramon Muntaner and Bernat Desclot were eyewitnesses to the apex of Aragonese power, in Tirant lo Blanch, Martorell and Galba give voice to a nostalgia for this lost power, while making frequent use of material from these chronicles. In a way Tirant is a historical-fictional fantasy of what the Aragonese expansion in the Eastern and Southern Mediterranean might have been if the Ottoman Empire had not come to dominate the region (Piera 53).

Accession of Mehmed II in Edirne,1451 depicted in a 1523 painting housed in the Topkapi Palace Museum (Wikimedia Commons)

This literary expansionist fantasy is fueled both by historical regret at the loss of Aragonese and Byzantine holdings in the Eastern Mediterranean in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, but also by the contemporary concerns of the war with Granada in the Iberian south and Ottoman expansion in the East. The loss of Constantinople to Mehmet II in 1453 was still felt in Western Europe, which looked on lamely as Mehmet II continued to expand his empire, soon conquering all of Anatolia as well as the Balkans. Toward the end of his reign he even staged successful campaigns in the Western Mediterranean, taking and holding the Italian city of Otranto in 1481, only nine years before Tirant’s publication (Giráldez 24). One chronicle of the Catholic Monarchs calls the fall of Otranto a “horrible plaga.” (Bernáldez).

These events only intensified Latin Christendom’s nostalgia for Crusade and a Christian East, and crusading literary models continued to be pressed into contemporary service in order to cope with anxieties over a Mediterranean that was increasingly under Muslim control, even as Christian Iberian monarchs were pushing to rid their own land of Muslim political power. Such fears would be further vindicated under Suleiman the Magnificent, who expanded imperial holdings to include nearly all the locations featured in Galba’s continuation (Tlemcen, Alexandria and the former Crusader states in the Levant).

Constantinople played an important role in this symbolic game of chess, as the former Byzantine capital and modern legacy of Roman imperial power. Curiously, as Paloma Díaz Mas points out, the Iberian historiography of the time is nearly silent on the fall of Constantinople (Díaz Mas 343–44). Luckily, the romance as ever jumps in to exploit the silence. Tirant’s eventual ascent to the Byzantine throne is a vivid vindication of Christian interests in the region, one rooted in history if not exactly respectful of the historical record.

Islam in Tirant

In Martorell’s day, Granada had been reduced to a totally dependent client state of Castile; the Islamic threat to Christendom now came from the Ottoman Eastern Mediterranean. Tirant, like the crusader knights of the golden era of the chivalric romance, answers the call (Rubiera Mata 14).

Tirant’s defense of Christianity is both military and proselytic, and he has help. After the conversion of the Ethiopian King Escariano, the Valencian friar Elias, just back from ransoming Christian captives in North Africa, helps Tirant baptize King Escariano and Queen Emeraldine’s subjects. In a few short days the text relates that “he set 44,327 infidels on the path to salvation” (Martorell and Galba 486).

Earlier romances by Christian Iberian authors, such as the Libro del Caballero Zifar, prominently feature conversion scenes as a part of their chivalric world. These representations are a direct reflection of historical reality. Less than ten years after the publication of Tirant this is precisely what happened in Spain in the very name of defending Christianity: the mass expulsion and conversion of the Peninsula’s Jews, and a decade later, the mass conversion of the Peninsula’s Muslims. History very clearly demonstrates that the dream of mass conversion novelized in Tirant is less a fantasy than a rehearsal.

In fact, the fictional mass conversions of the North African Saracens carried out by Tirant’s Valencian friar comes with a warning about the social price of mass conversions, with specific reference to the city of Valencia in the future, which we can assume refers to the time of Martorell and Galba:

In the future, Valencia's wickedness will be the cause of its downfall, for, according to Elias, it will be populated by nations of cursed seed and men will come to distrust their own fathers and brothers. According to him it will have to bear three scourges: Jews, Saracens, and Moorish converts (Martorell and Galba 486).

Hindsight, as they say, is 20/20. This bit of prophecy from the aptly named friar Elias, (the Greek form of Elijah) is spot on. Already by 1490 there was a considerable class of new converts from Judaism, the conversos, whose existence was causing no little social and economic anxiety among the well-to-do of Valencia. The question of the unconverted Jews and Muslims likewise was coming to a head in the Spain of the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand and Isabel, and would, as we all know, culminate in just two short years in the expulsion of the kingdom’s Jews, shortly followed by the forcible yet very superficial conversion of Valencia’s sizeable Muslim population.

In conclusion, Tirant lo Blanch fuses domestic and geopolitical concerns about Eastern conquest and domestic crusade and conversion from the Golden Era of French chivalric novels with those of Martorell’s fifteenth-century Valencia. The novel reimagines the chivalric of the Arthurian world in a specifically late-medieval Valencian key, both projecting local concerns onto the Arthurian storyworld and infusing current reality with Arthurian chivalric values. In this world, Moors attack England, the hero rules over a Byzantine Constantinople, and a wildly successful Valencian proselyte predicts the downfall of his hometown to his own successful endeavors to convert local Jews and Muslims. Tirant is emblematic of the power of fiction to represent the present by reimagining the past.

Works Cited

- Bernáldez, Andrés. Memorias del Reinado de los Reyes Católicos,. Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia, 1962. Print.

- Brownlee, Marina. “Iconicity, Romance and History in the Crónica Sarracina.” Diacritics 36.3-4 (2006): 119–130. Project MUSE. Web. 23 Feb. 2010.

- Díaz Mas, Paloma. “El eco de la caída de Constantinopla en las literaturas hispánicas.” Constantinopla 1453: Mitos y realidades. Ed. Pedro Bádenas de la Peña and Inmaculada Pérez Martín. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, 2003. 318–349. Print.

- Fallows, Noel. Jousting in Medieval and Renaissance Iberia. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Boydell Press, 2010. Print.

- Fuchs, Barbara. Romance. New York: Routledge, 2004. Print.

- Giráldez, Susan. Las Sergas de Esplandián y la España de Los Reyes Católicos. New York: P. Lang, 2003. Print.

- Hillgarth, Jocelyn. The Problem of a Catalan Mediterranean Empire, 1229-1327. London: Longman, 1975. Print.

- Lowe, Alfonso. The Catalan Vengeance. London: Routledge and K. Paul, 1972. Print.

- Martorell, Joanot, and Joan de Galba. Tirant Lo Blanch. Trans. David H. Rosenthal. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1984. Print.

- Riquer, Martí de. “Joanot Martorell i el Tirant lo Blanc.” Tirant lo Blanc. Vol. 1. Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1970. 7–94. Print.

- Rubiera Mata, María Jesús. Tirant contra el Islam. Alicante: Ediciones Aitana, 1993. Print.

* David Wacks is Professor of Spanish at the University of Oregon. He is author of Framing Iberia: Frametales and Maqamat in Medieval Spain (Brill, 2007) and Double Dispora in Sephardic Literature: Jewish Cultural Production before and after 1492 (Indiana UP, 2015). His research focuses on the literary footprint of the confluence of Christianity, Judaism and Islam in medieval Iberia. Currently he forms part of an international team of scholars devoloping a collaborative, online commentary of a 13th century Spanish Biblical text, the Estoria General that examines the contributions of Islam, Judaism and Christianity to the study of the Bible in medieval Spain. He maintains a research blog geared for a non-specialist audience at: http://davidwacks.uoregon.edu.

The original version of this paper is posted at: http://davidwacks.uoregon.edu/2015/04/11/tirant/